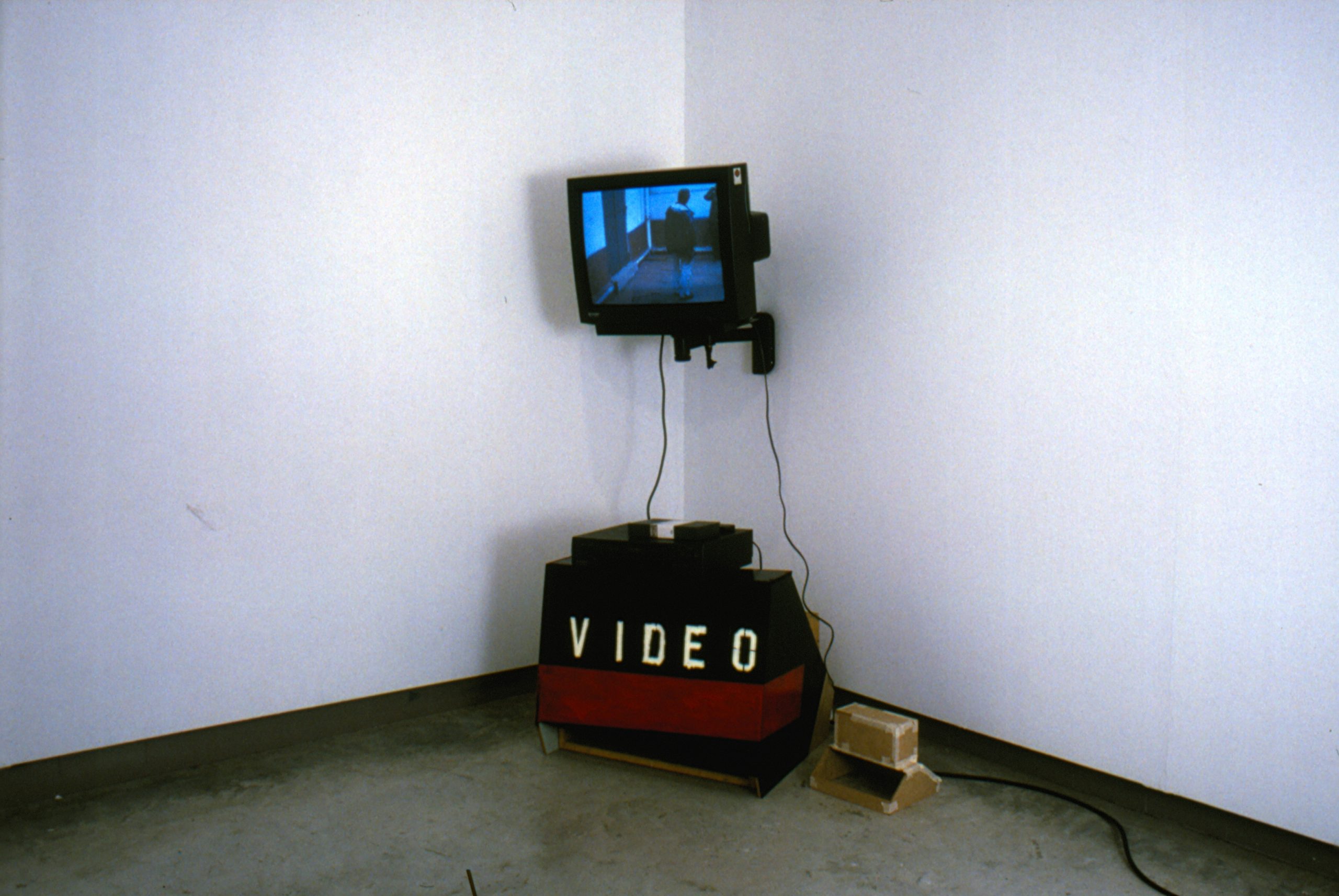

→ Me voy a ir, me voy, estoy ido. San Sebastian, DAE-Donostiako Arte Ekinbideak : Egia Cultural Centre, 28 May – 26 June 1999.

Videos

I believe that from the first Fissures to the current Massages there is a core of concerns that is maintained and whose development is constant. A continuous research over time that results in unique solutions. For me, the Massages are a step further in Idoia’s process of transcending frontality, a step in which her practice aims for a haptic feeling that links her to artists such as Lygia Clark or Helio Oiticica. With Idoia, in her Massages, we see through the skin and through the ear, we touch with the eye, we produce images directly inward. She does not refuse to produce images, but she does renounce to produce clear, directed, located, separate and distinct images. Sensibility and thought are worked as a web of relations, blurring the distinction established by our western conception of the functioning of the senses and logic, between the res extensa of the body and the res cogita of the mind. In the Massages, the distance between the audience and Idoia finally tends to blur. Idoia’s commitment as an artist grows exponentially from the Fissures to the Massages. In the first ones, a strong impulse wins the game and there is no negotiation with the world. As her career progresses and her research develops, first in the Mantras, and even more in the Massages, Idoia’s agency grows and along with it the will to transform the world from the basics; to expand perception and thus redistribute the territories given to materiality, thought and experience. Text Massage (2017) seeks to touch with words, to wrap you in them like a mantle and to move you. In Vision Massage (2019) the images and movements are created in the body of the audience, they are produced in the inner movement of the sensations of the person receiving the massage. The body of the performer and the body of the spectator fade their boundaries as separate and distinct elements, both participating in the same sensorium, also blurring the supposedly active function of the performer and the supposedly passive function of the audience. The eye is treated as a tactile surface while images are created through the ear by listening. Everything is fluid and indistinct, sensorial and changing. In Scanner Massage (2023), the extremes touch each other in the R, from radical to romantic, rare, radiant. The R of vibration, of rose, of laughter. In Idoia’s words, “the stroke of the R is a symbol, a sign, but also a drawing that touches your face”. Idoia creates processing machines, what Karen Barad calls intra-actions, processing machines that are in themselves choreographic and whose aim is to help us touch by thinking and thus open up, in the words of Marie Bardet, a breach in the Cartesian monument.

Idoia often says that her dancing has always had a speech, a kind of blah-blah. The question of speech, the distortion of speech, the inclusion of theatrical elements in dance links her to Meredith Monk, for example, but more closely to Itziar Okariz, Amaia Urra, Ixiar Rozas, to a generation of artists linked to performance who have worked on speech, language and the word within a discipline organised around the body. All of them speak but, like Idoia, they reject the clarity of discourse. In the fissures, Idoia uses her own speaking as a way of opening a crack in the primacy of the frontal, central, distanced, flattened gaze. She seeks to touch the other with her words, to appeal to the other, often directly, to try to sum up the distance that separates them. In the Mantras, however, she begins to unfold the potencies of that moving by speaking. The attention has already slipped from the body to language and to the choreographic powers of the spoken word. The Mantras seem an escape path from the way she used language in her previous performances, in a straight line, to go through, like a vector. In order to transcend it, Idoia begins to manipulate what she was using instrumentally to fissure the mutism of a dancing body. In Fissures she used speech to create displacements, movement, after all. But how to think language if not with language itself, how to exercise its movement, how to encourage it, to wave it, how to transcend its frontality? The earliest documented Mantras are audio recordings. Idoia tells us that these Mantras often appear while driving in a car. The landscape moves quickly, the foreground blurs and perspective twists, everything is mutable and fluid outside while moving at high speed, but in the cockpit, driving requires a discipline and technique that puts the body on alert. You have to change gear, respect traffic signs, remember the turn, turn on the indicator. In the collision between these two forms of perception, is where Idoia’s Mantras are often born, like a sonnet. Then she goes to the studio and works on them. There is no outside movement, the white walls, the wooden ceiling of Azala define the space like a constant. The body, on the other hand, is free of constraint. There is no need to mark, reduce or give way. This is where the audio recordings that are the basis of the Mantras are created. In them, a kind of phrases are worked out, repetition structures with tonal variations that are modulated in a serial way. Many of the Mantras start from structures based on binarity (while you X I Y, they X we Y). Once again, the initial elements confront each other. In all of them, Idoia begins to work on the materiality of the voice as a becoming and the saying as a movement. Through the Mantras she focuses her work on all those potentialities that escape from the scheme of modern rational scientific thought and language ceases to be straightforward. In this series, there is a stronger work with sensations, with how it feels to pronounce this or another word, what gesture produces a g, how an m moves me after a g, what images they shape. Idoia twists and plays with language, diction and tone to create images in transformation, to foster an in between that opens up possibilities of zigzagging, swirling, escaping. When I think about the process of creating the Mantras in order to be able to write, I fall into shadows, I think that I am thinking and I become obsessed. The performance aims for a continuous present, I tell myself; that’s what Idoia is looking for. And then I doubt, and a song by Pepe Suero (Andalucía la que divierte, 1978) that I used to listen to with Vicente comes to my mind like a mantra. The song goes like this: “I think I die when I think, I think that thinking I die (…) I think I live when I sing, I want to sing and I can’t (…) I die wanting to live, I think I live when I sing, I want to sing and I can’t, I think that thinking I die, I think I die when I think”.

On returning from her international tours with companies whose practice is based on improvisation, through which she got to know first-hand the farm of Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson in Vermont (USA), Idoia created La puta inocencia (2002) and El rato de José (2002). In both pieces she collaborated horizontally with other artists and dancers, and her success opened up a slot for her among the Basque choreographers of the early 2000s. One of the invitations to stage this figure, that of the Basque choreographer presenting a piece in the Guggenheim Hall, was the origin of the second Fissure, Txoriak (2007). Txoriak is the second in a series of pieces with common features that Idoia groups under the title Fissures. All of them deal with frontality as a coercive element. Facing, going head-on, implies a distance towards the other. I am here and you are there, between us, a distance opens up. Although our foreheads lean against each other in mourning, what defines us continues to be that in-between, that emptiness that both organises and separates us. Fissures can be considered a study in progress of this split, of frontality as a structuring element in dance, but also in social and political choreography (the demonstrations and marches she grew up with in her native Gasteiz), as well as in interpersonal relationships or in the political and activist slogans that construct identity by confronting what we are not in order to define what we are. The Fissures are perhaps a study of how performativity in these different spheres, in family relations, in social and political struggles, in dance and also in gender are similar if we pay attention to frontality as a staging device. We march in crowds with a banner on the road in front of the oppressive state, we leave to confront what is expected of us at home, we show what we are capable of in front of a jury, an audience, on stage, we cut our hair and dress up to take the streets. In the Fissures, Idoia tries to open cracks in this structuring element, she strives to crack this given frontality, often by stressing the violent qualities that they impose as positions. We find in the Fissures a certain fondness for walls, surfaces, screens and walls as a trope. There is a continuous formal relationship between frontality and violence; in a way, the Fissures can be read as an attack on the arbitrary paradigm of frontality and its reductive character, producing an uninhabitable split. The frontal in Idoia’s Fissures flattens, crushes even, it is a conflictive heritage. Holes are opened in walls (Fisura nº4: per fora, 2012), and books are perforated (Fisura nª5: zuloak / neska eta mutila, 2013), the images of an action are superimposed on the action itself carried out live. In other cases, such as Fisura nª2: txoriak, the body is forced into a silhouette, into a series of flat, rigid figures for which movement is a pure transition between one hardened state and another. Idoia pierces encyclopaedias or paints a Martian on her breasts, waving her pelvis to distort the rigidity of the line (Fisura nº1, 2007). After all, t-shirts wear out, hair grows wild, and when you dig, you get mud under your nails, Idoia seems to be telling us. Water always finds a crack through which to escape, and laughter, as Bergson says, is an inarticulate sound that sprouts in search of an echo. When we witness the Fissures we clearly perceive that incorporating them hurts. Frontality and hardening injure bodies, whether our own or the social body, and this pain finds expression in the delirious gesture that inhabits these solos. The Fissures involve a certain hieratism. They harden the bodies, both of the one who performs them and of the one who contemplates them, and the resulting documents acquire an unsettling character. And if I am unsettling, it is because I am moving inside. Something dances inside me. The references to the material bases that gave shape to the Basque political conflict are clear in this series and their social correlates, such as drug consumption, slip in through figurative winks in Idoia’s works (Fisura nº6: zaldiak, 2016). Our bodies are altered. The same happens with the duality they entail. Idoia overcomes the contradiction in which she is immersed with a galloping howl. I perceive in them a certain animality opening up that can be revealed to us as abject, sexual or pathetic. We lack words.

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

20’20’’

DV PAL (720X540)

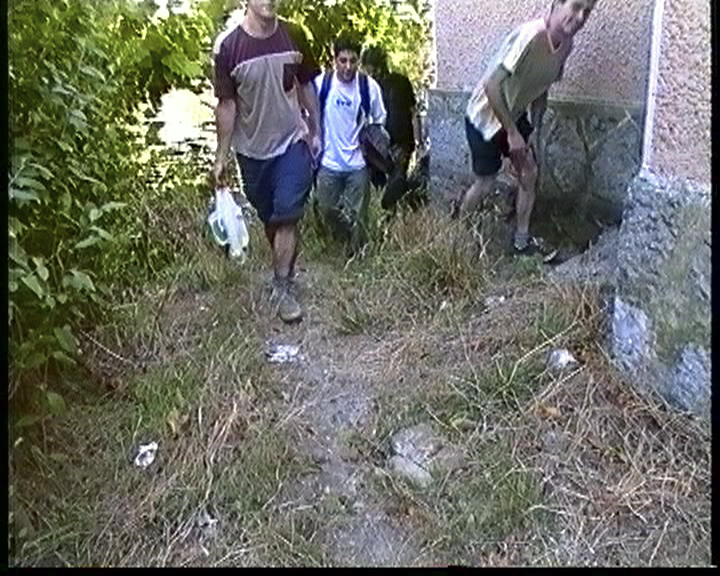

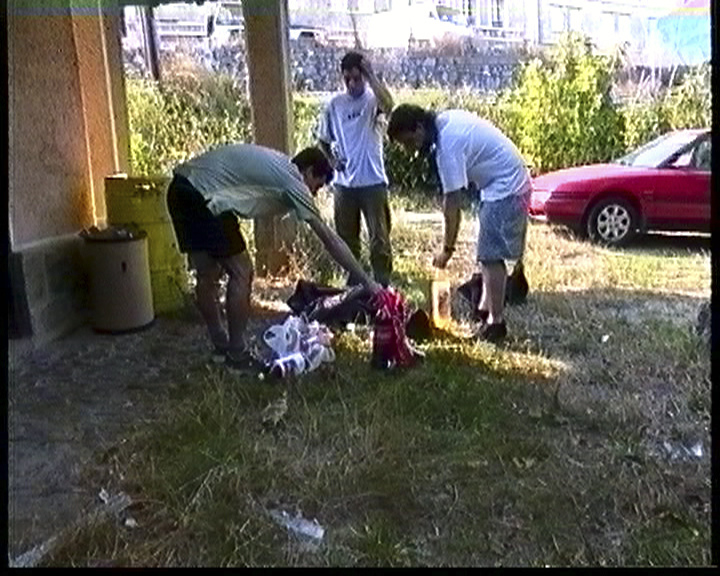

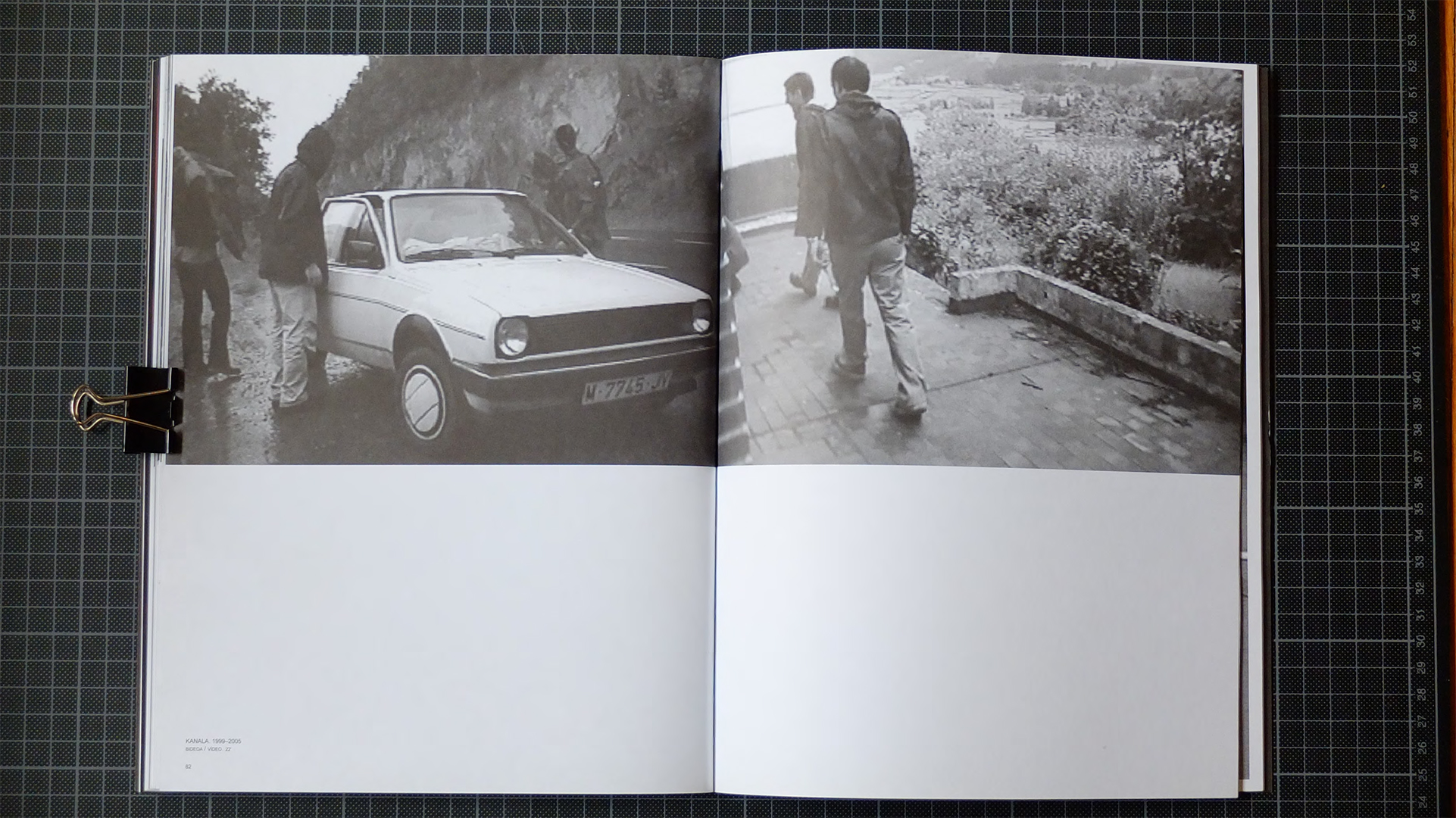

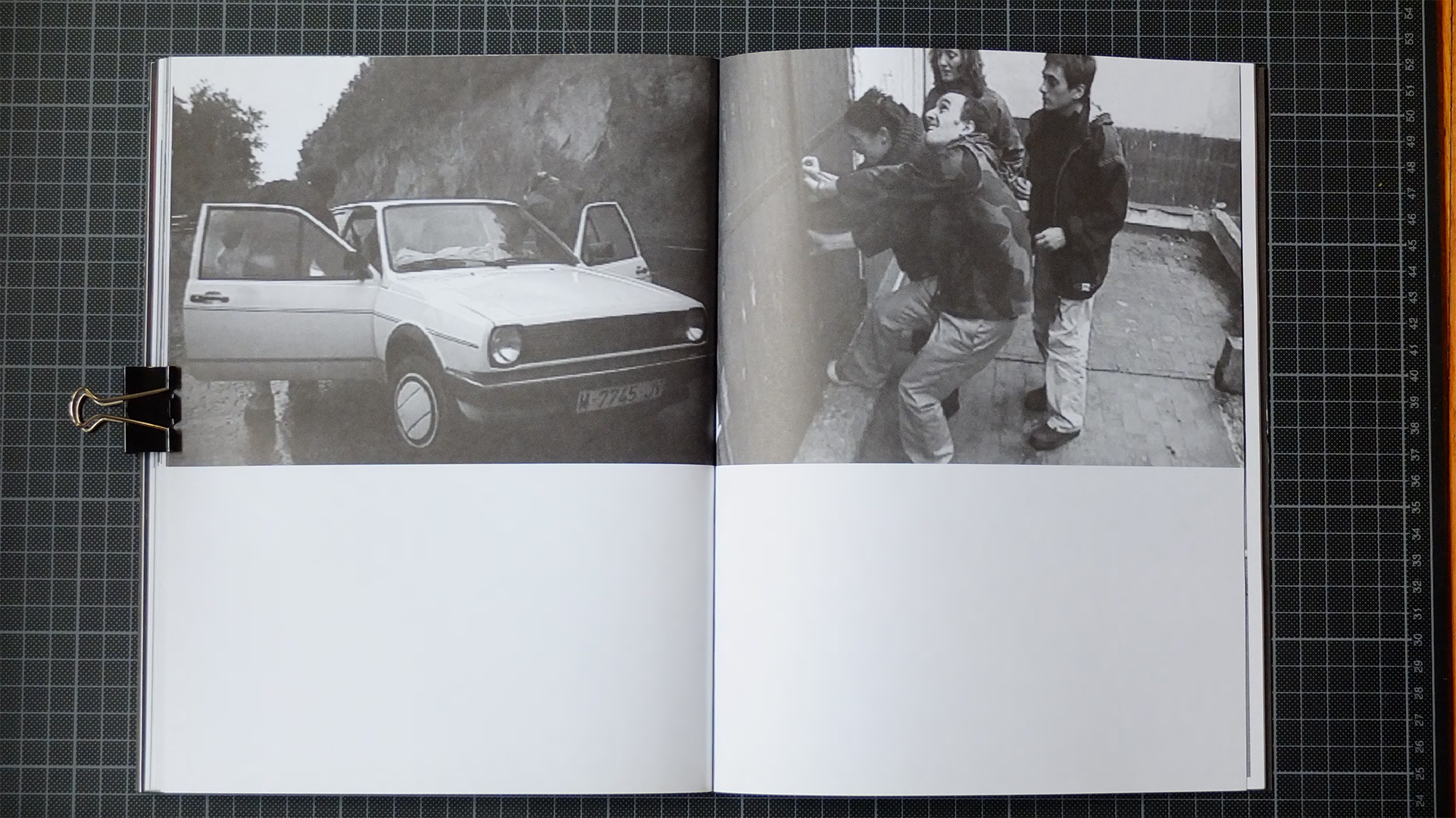

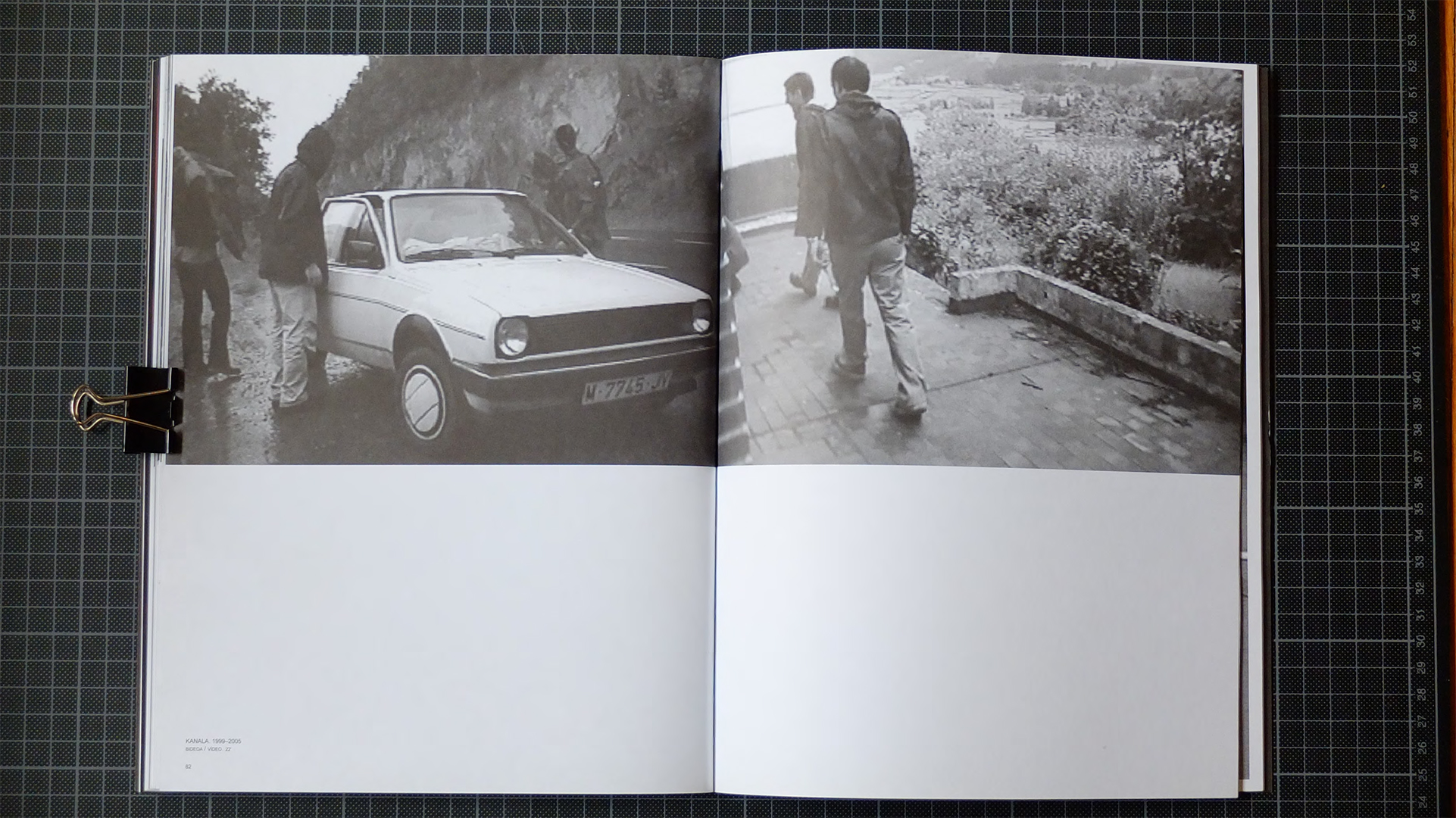

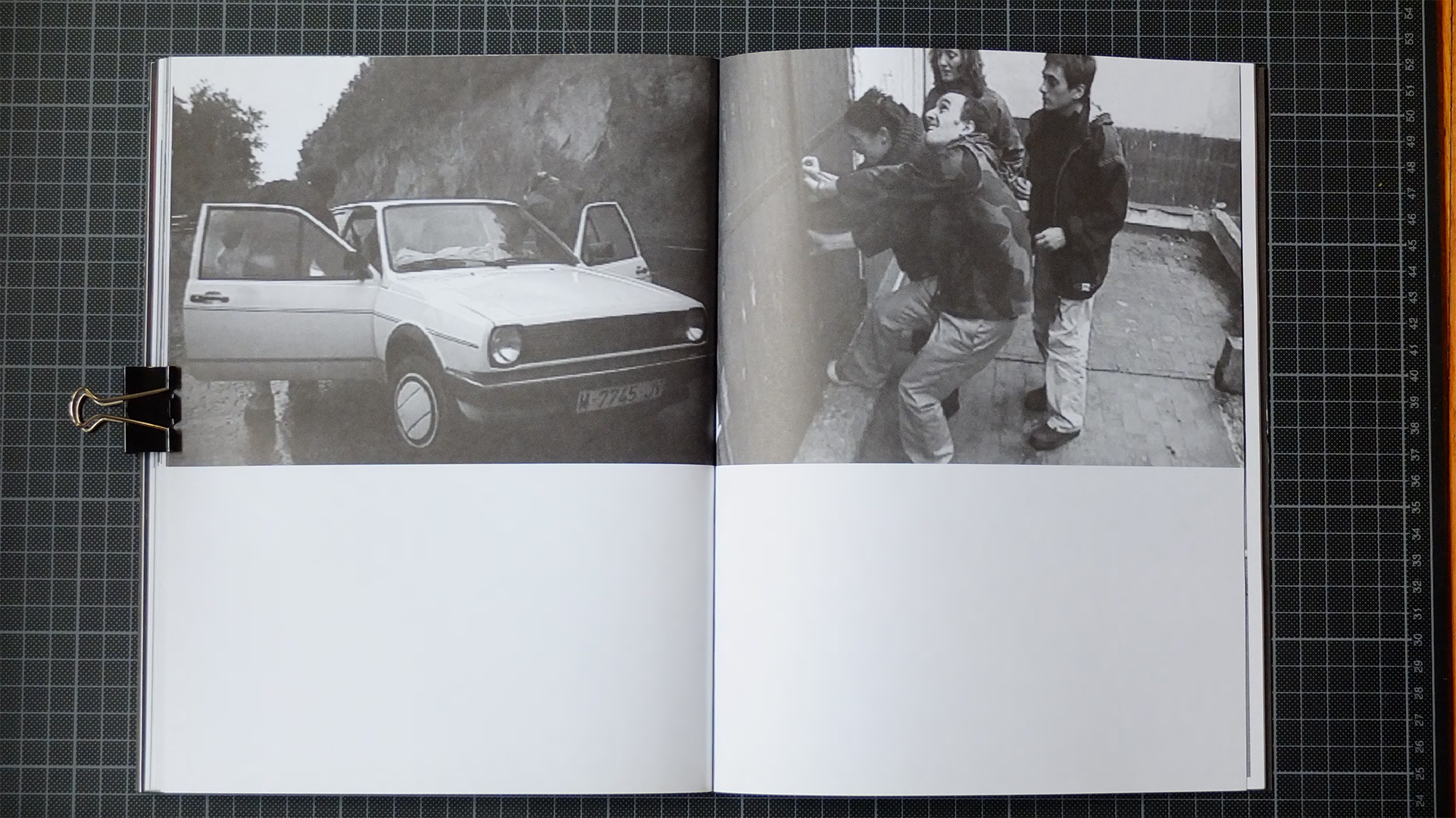

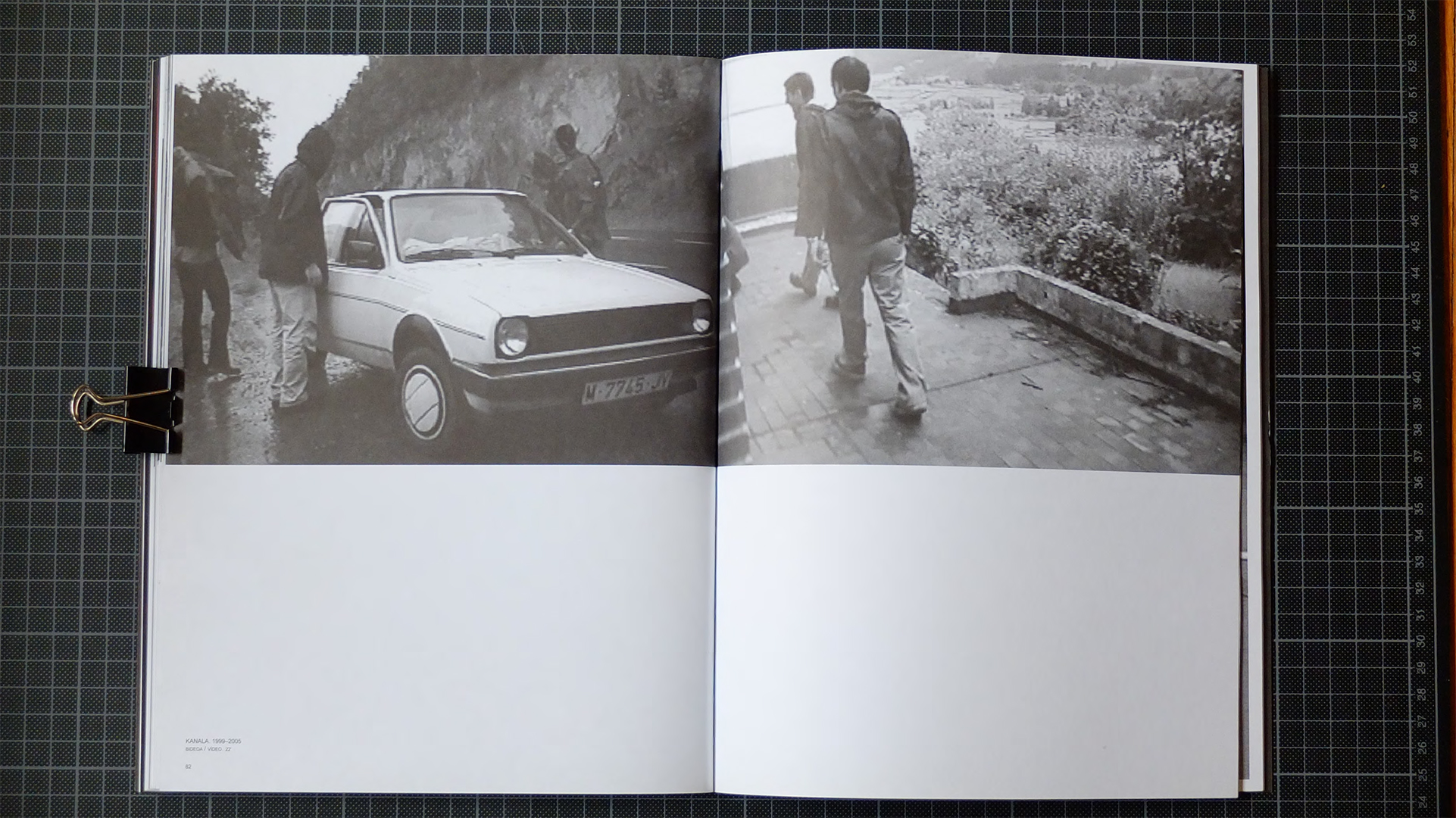

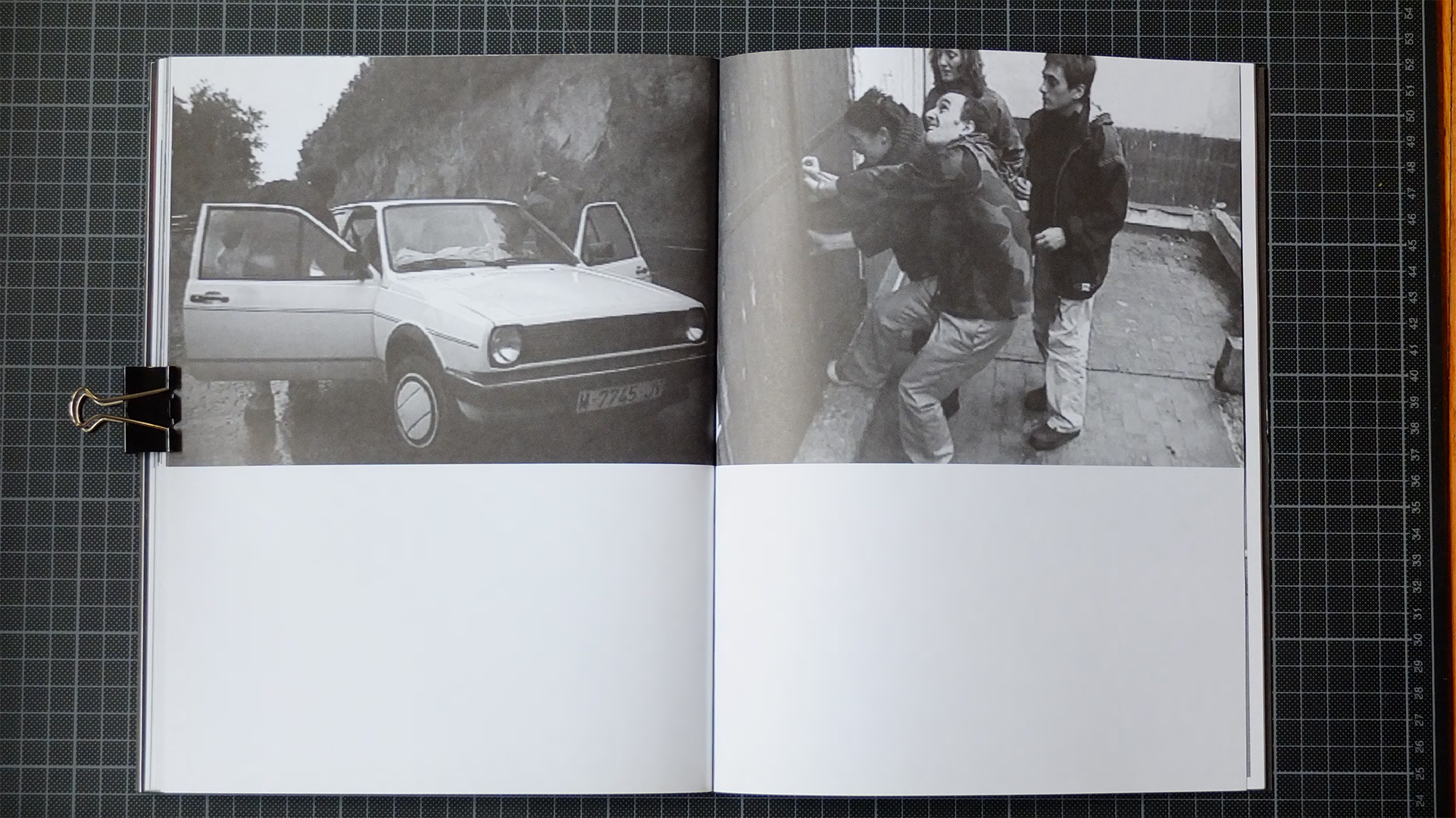

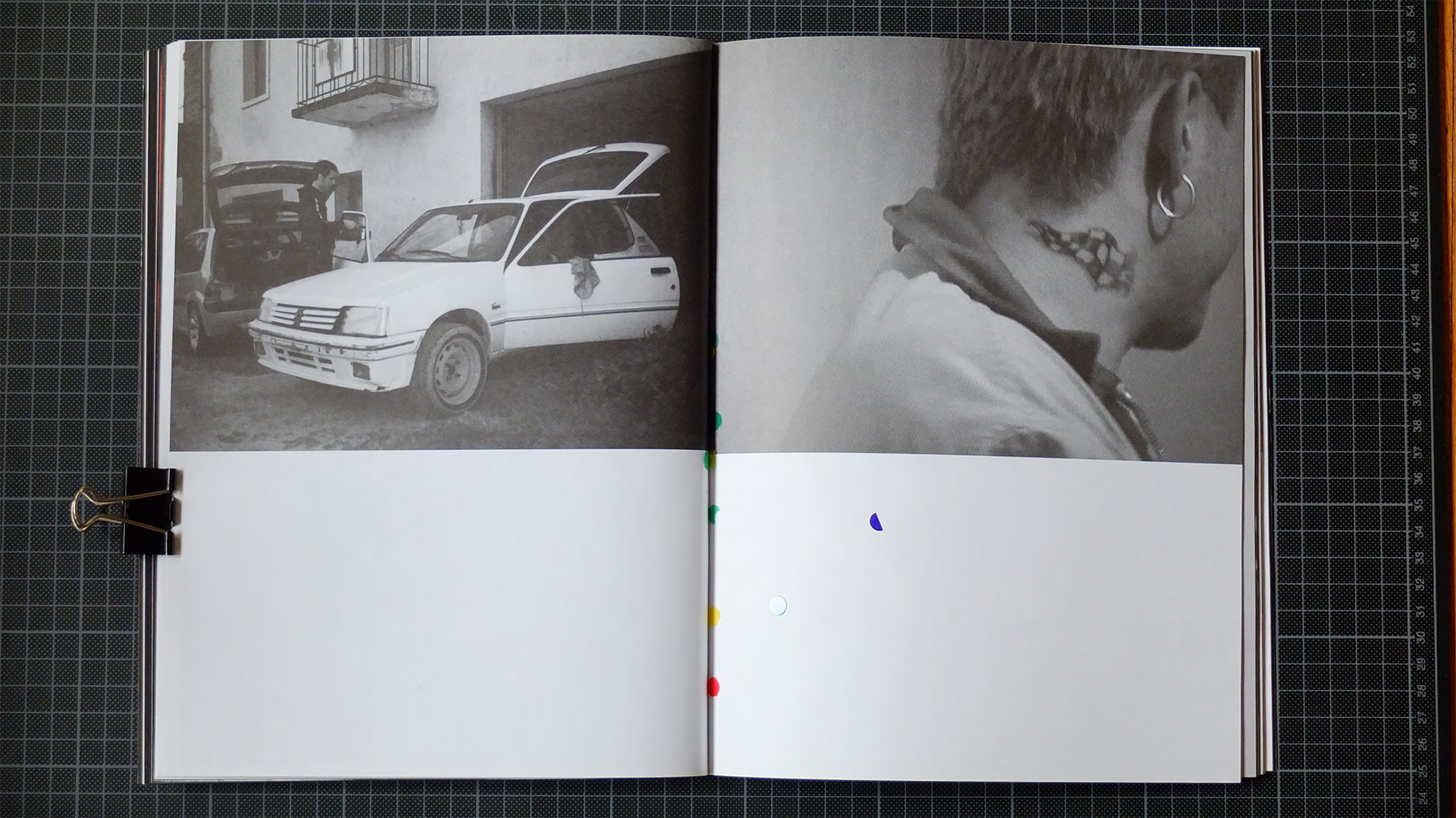

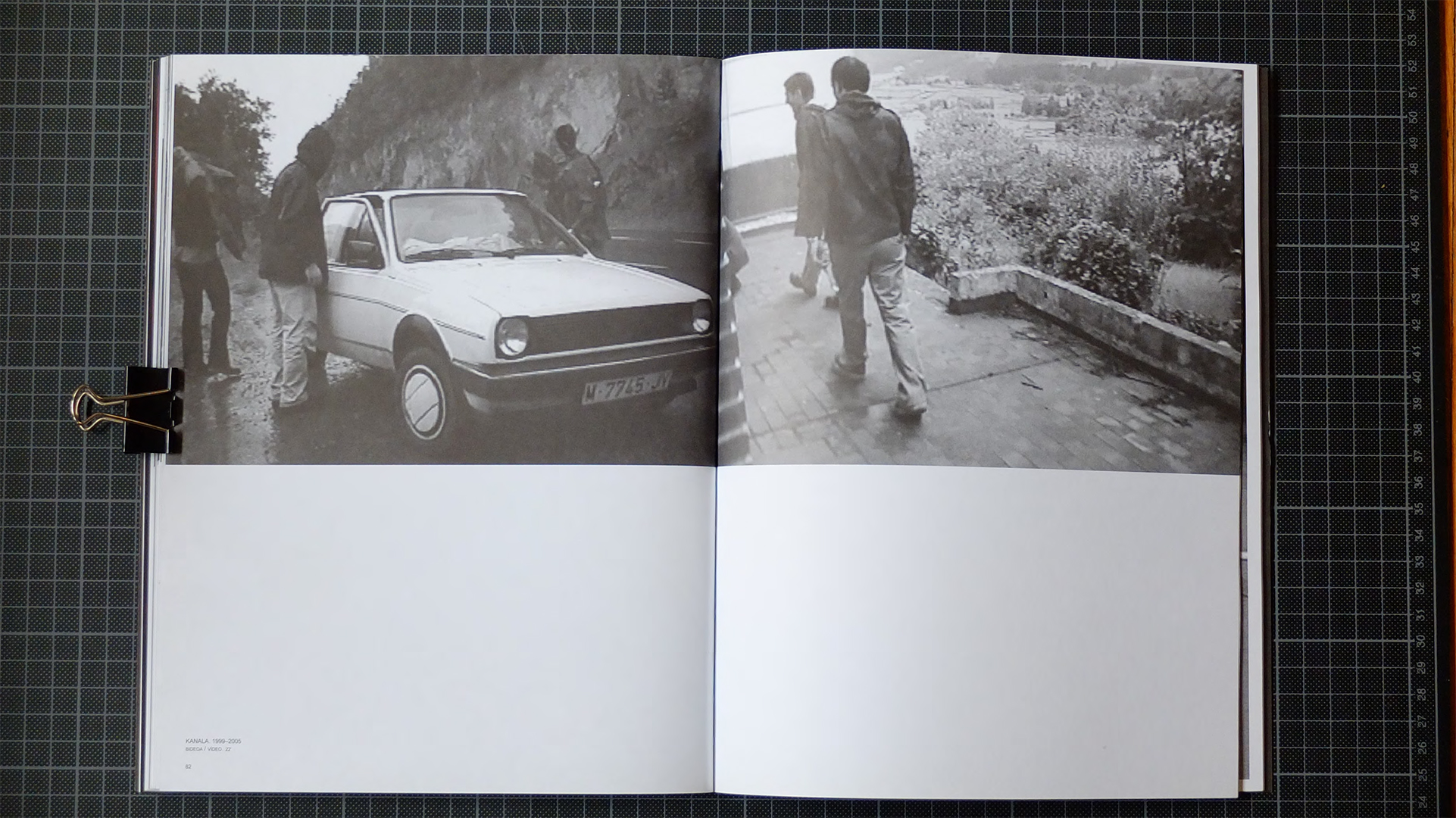

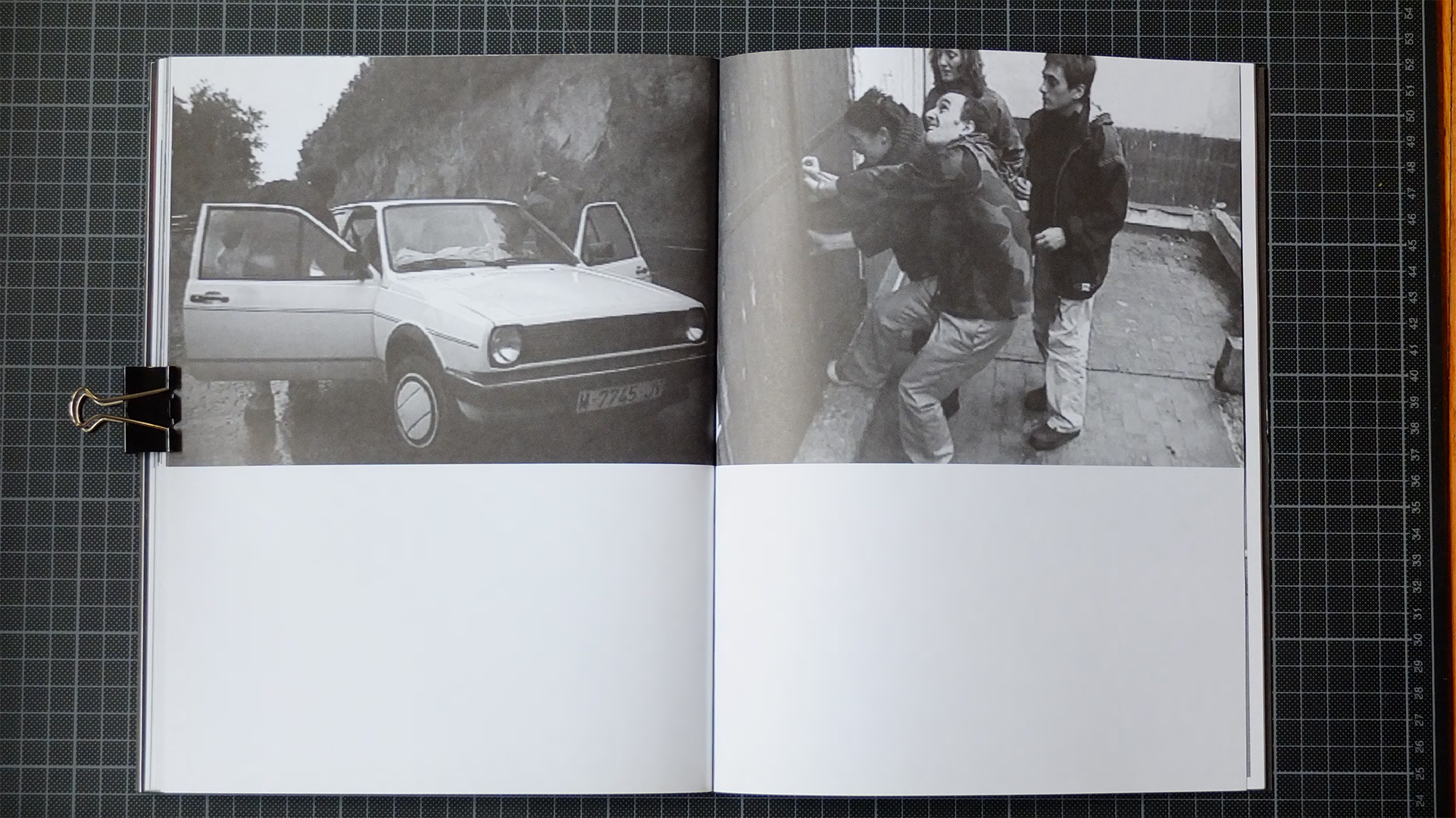

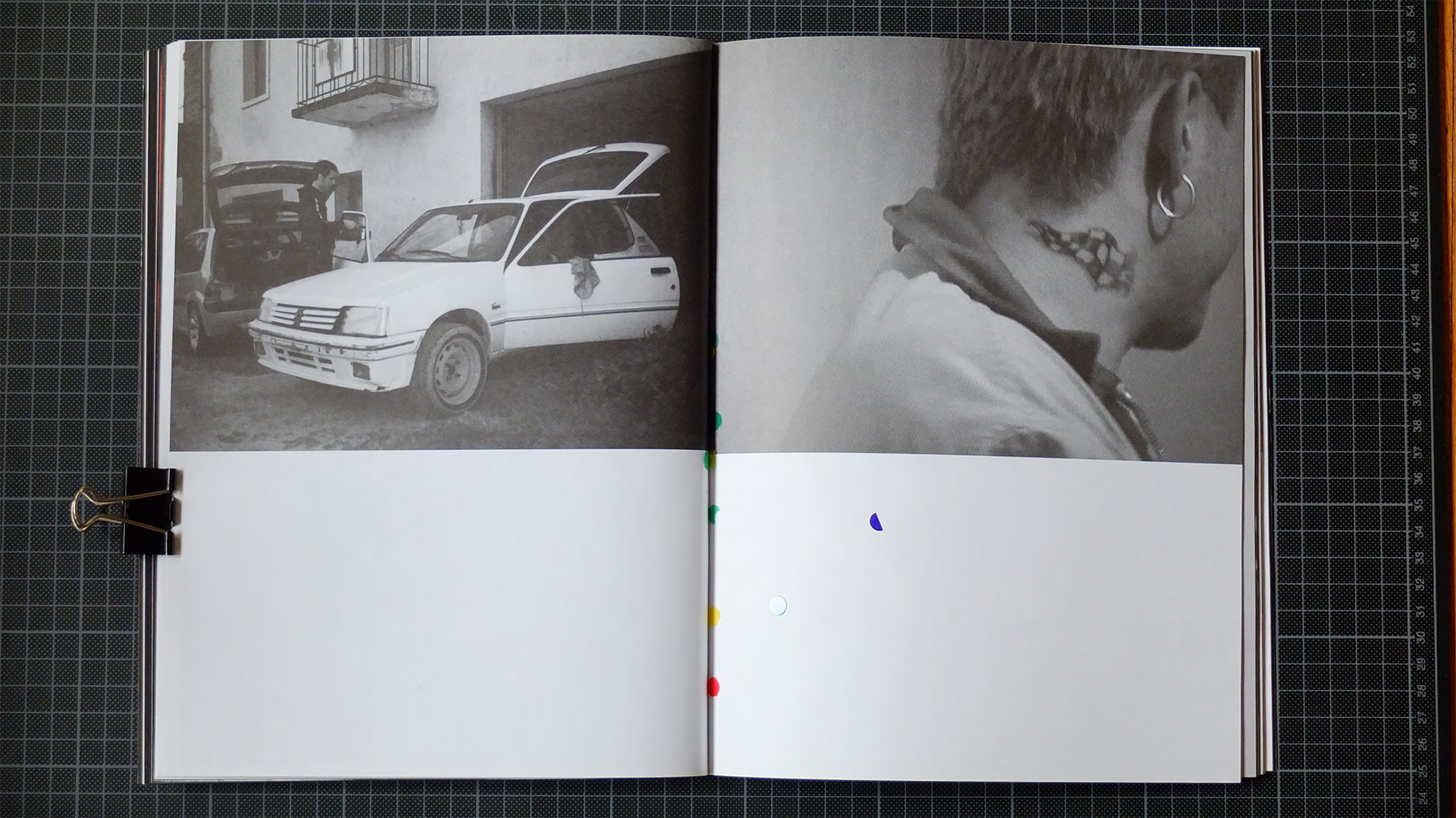

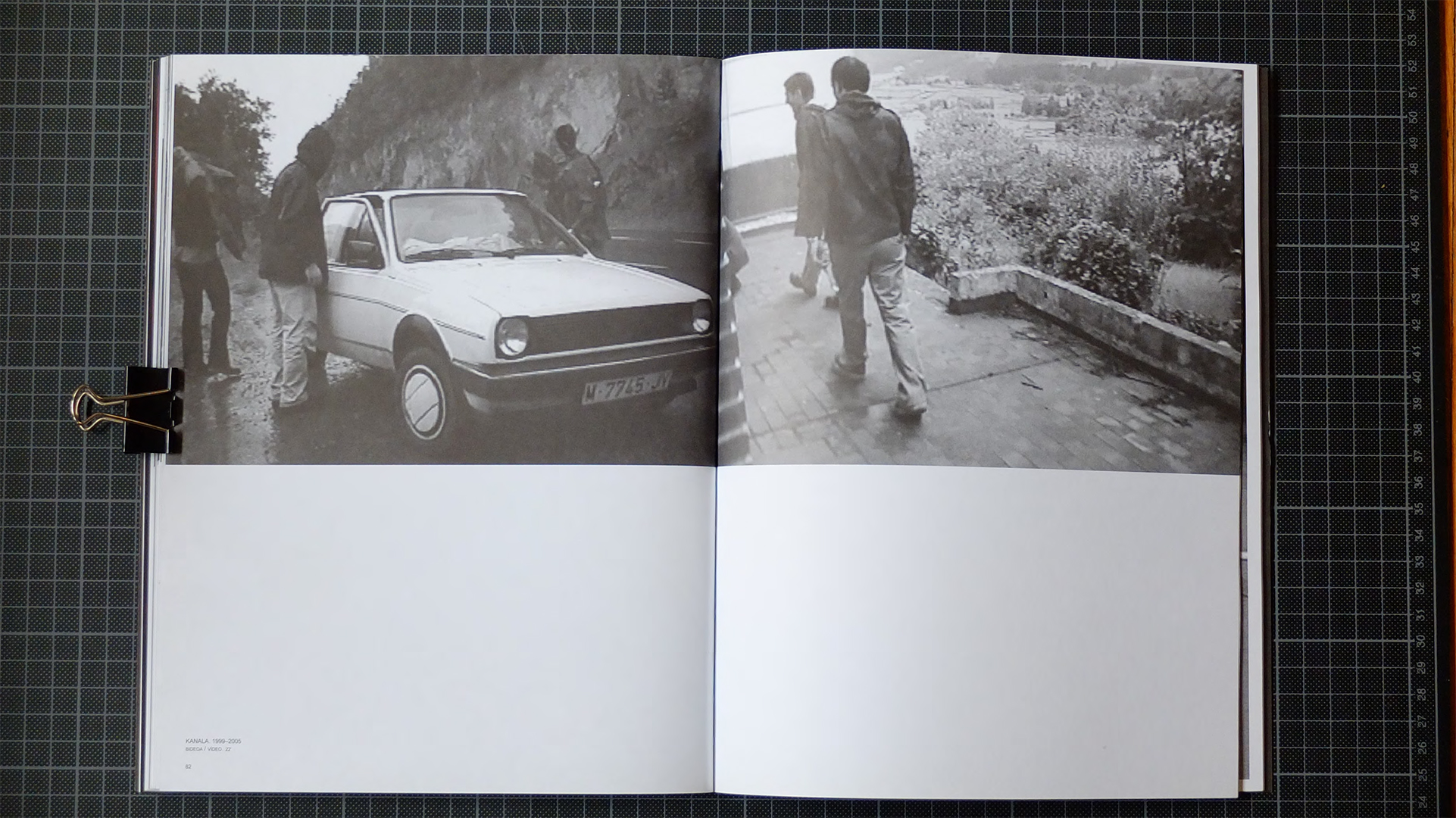

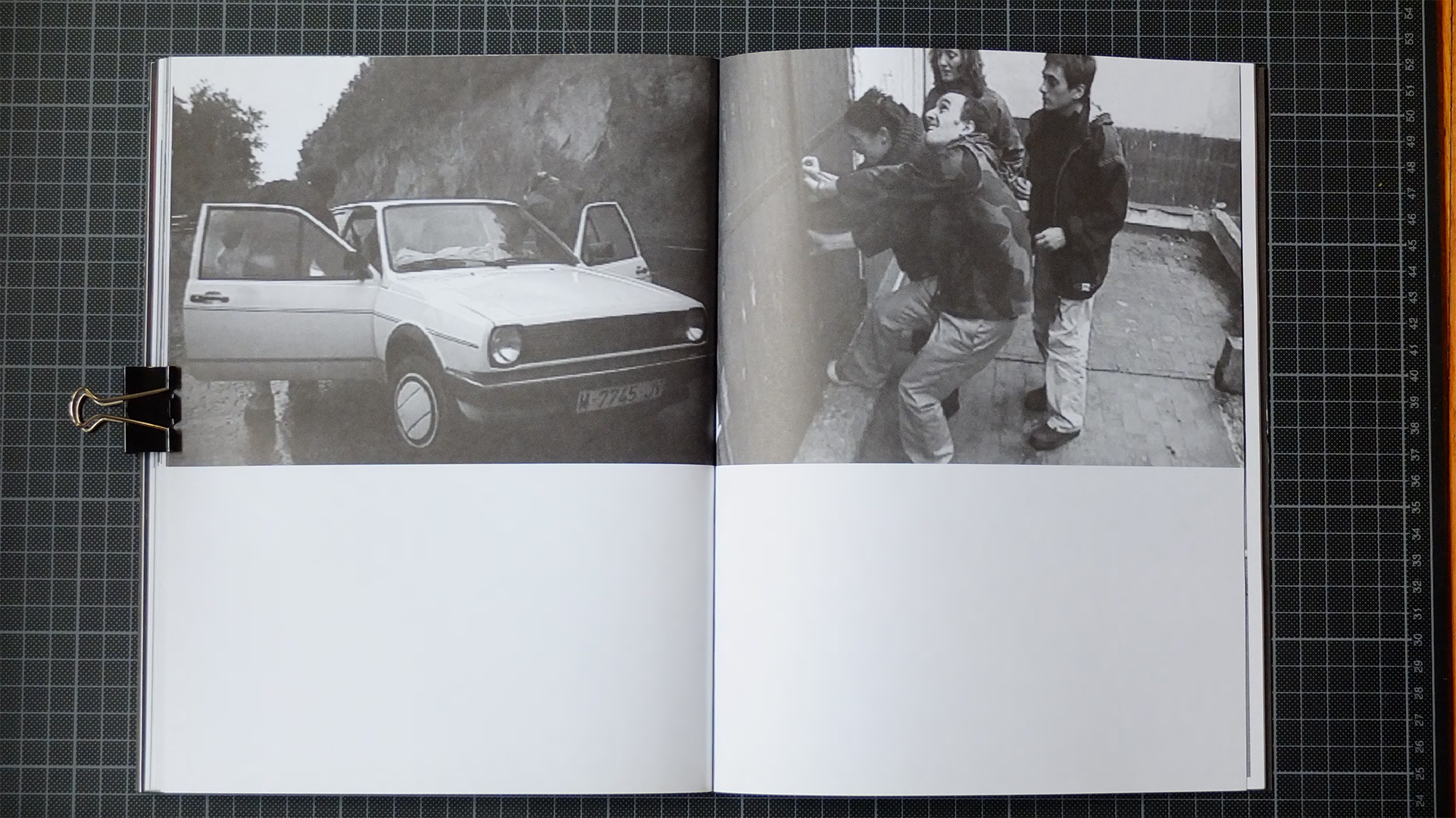

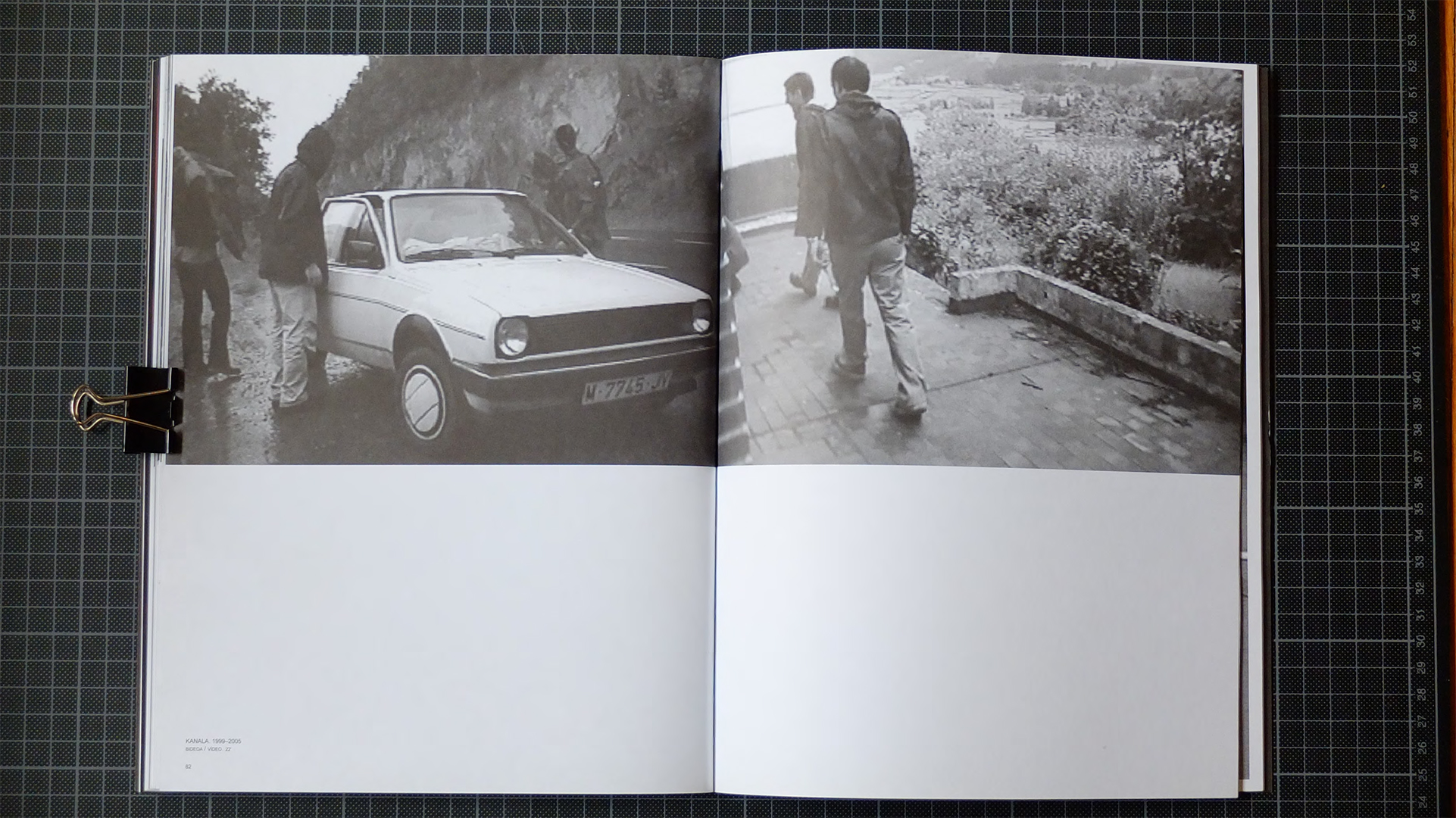

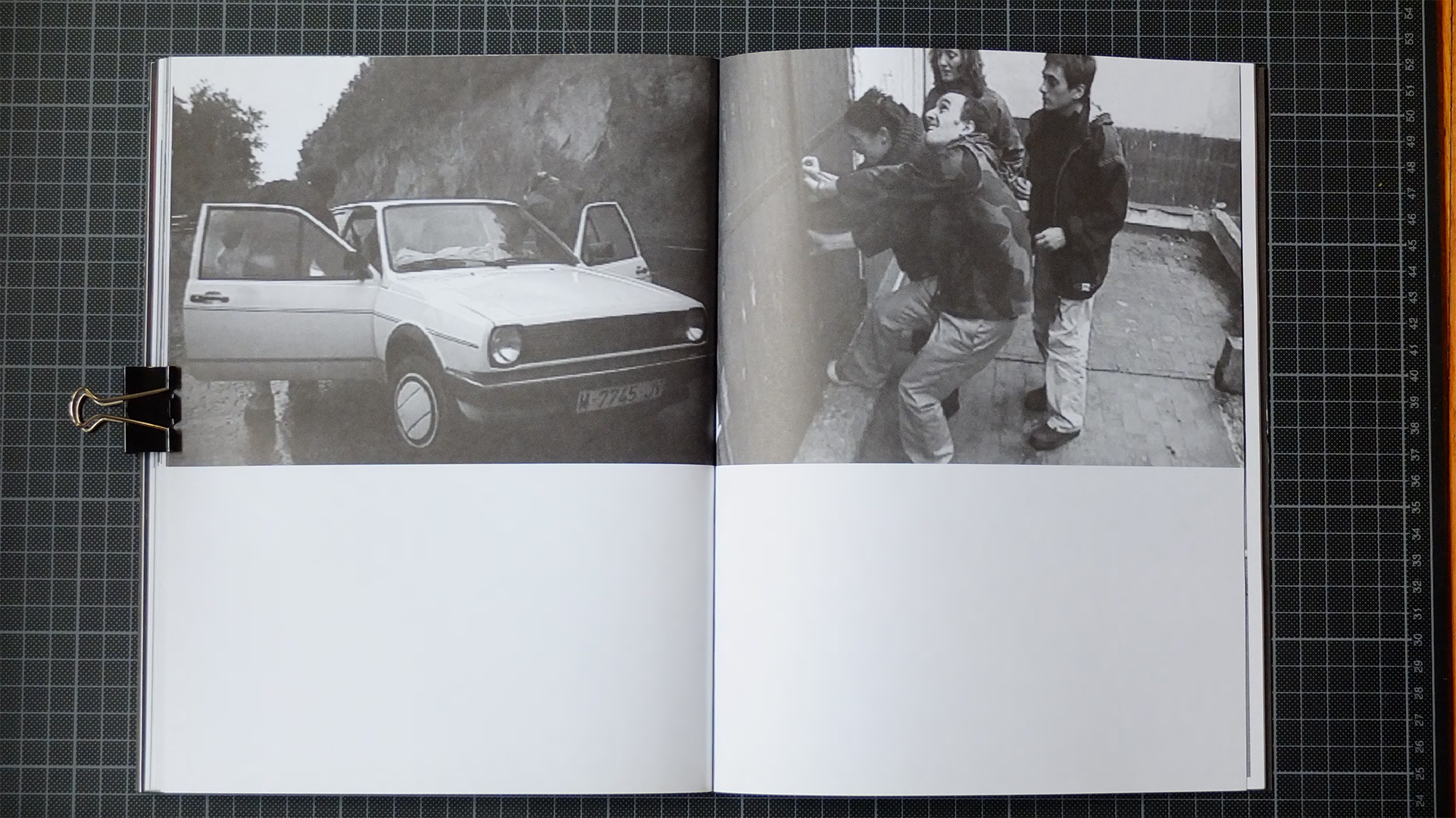

A group of young people step out of a white car with a Madrid license plate. They put their raincoats’ hoods up, it looks like it might rain. The scene changes immediately, taking us straight to the garden of a private home. The group goes over some notes written on a sheet of paper; Basque and Spanish mix up in an unplanned way. English has crept into the credits at the beginning of the video:

US vs THEM

Trying to get in: Chalet 1 & 2

- 1999 a video by Iñaki Garmendia

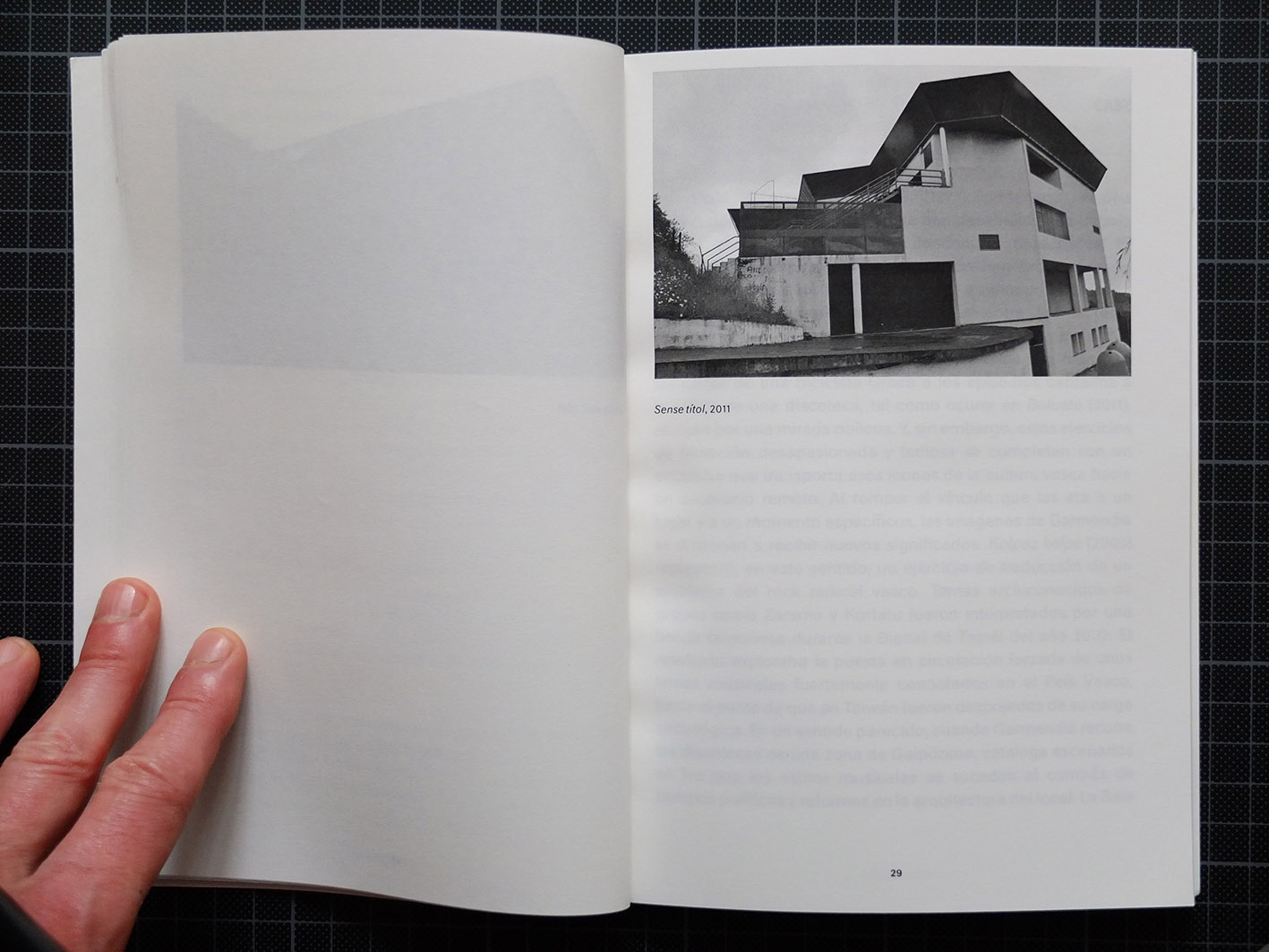

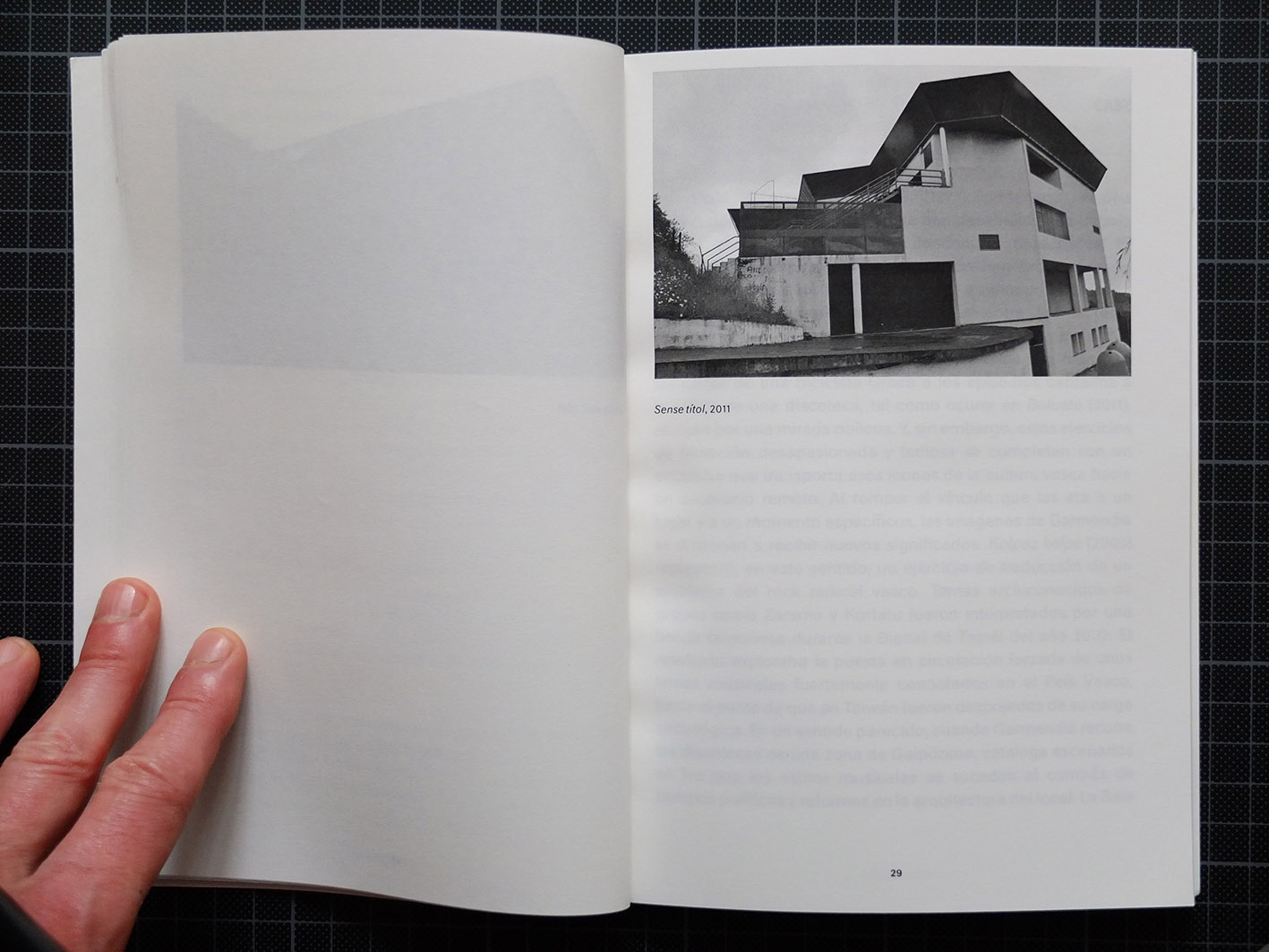

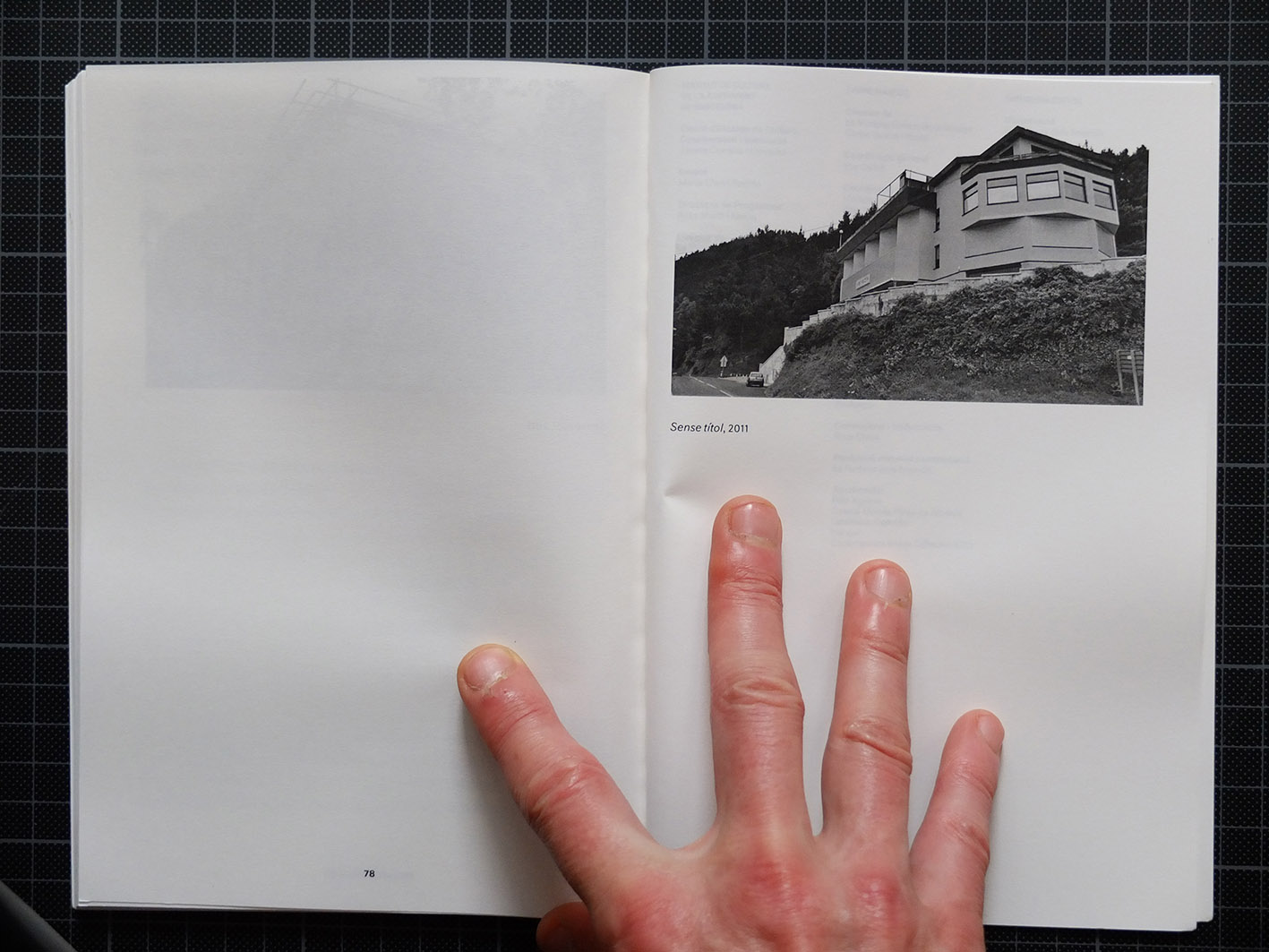

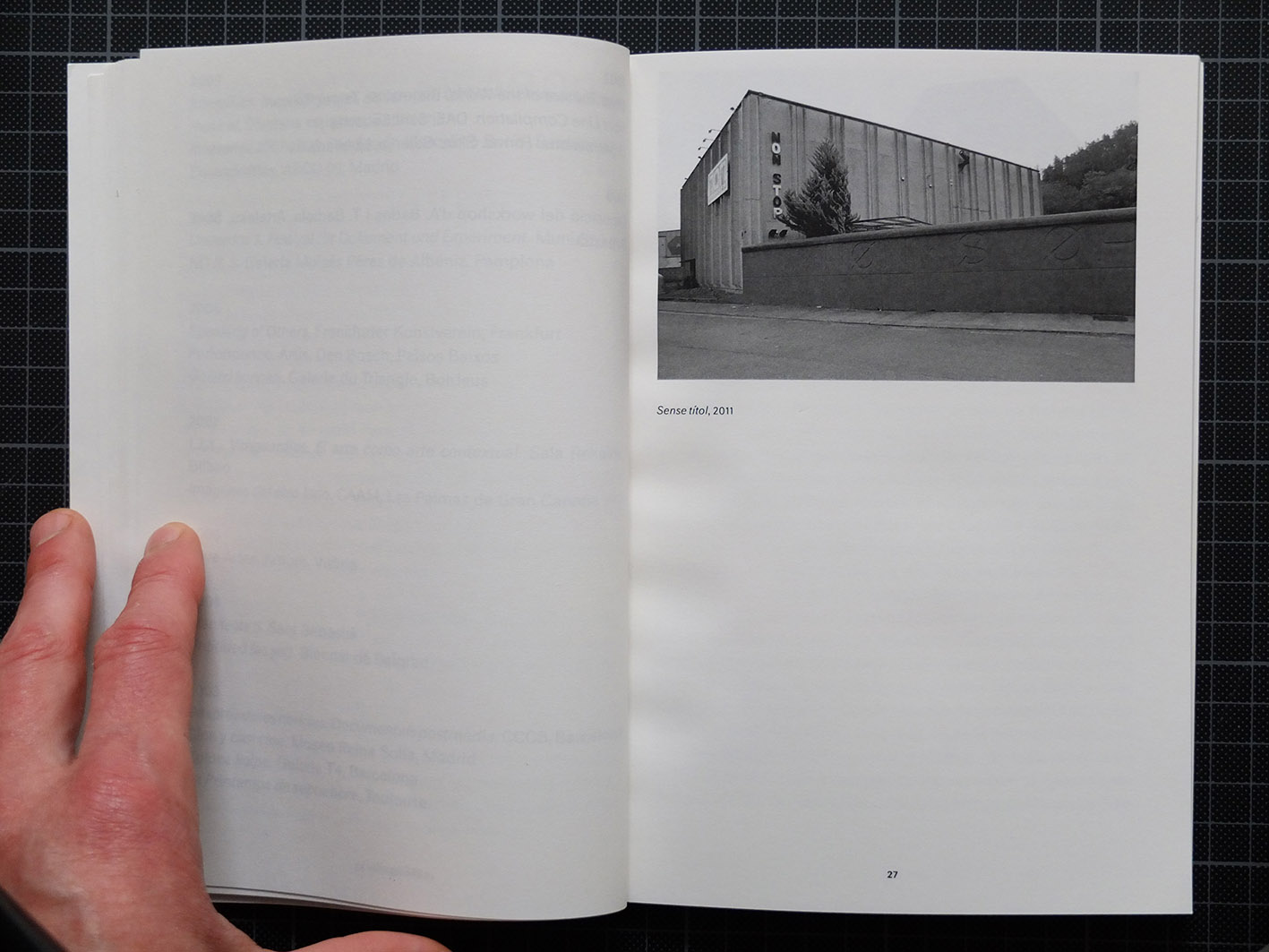

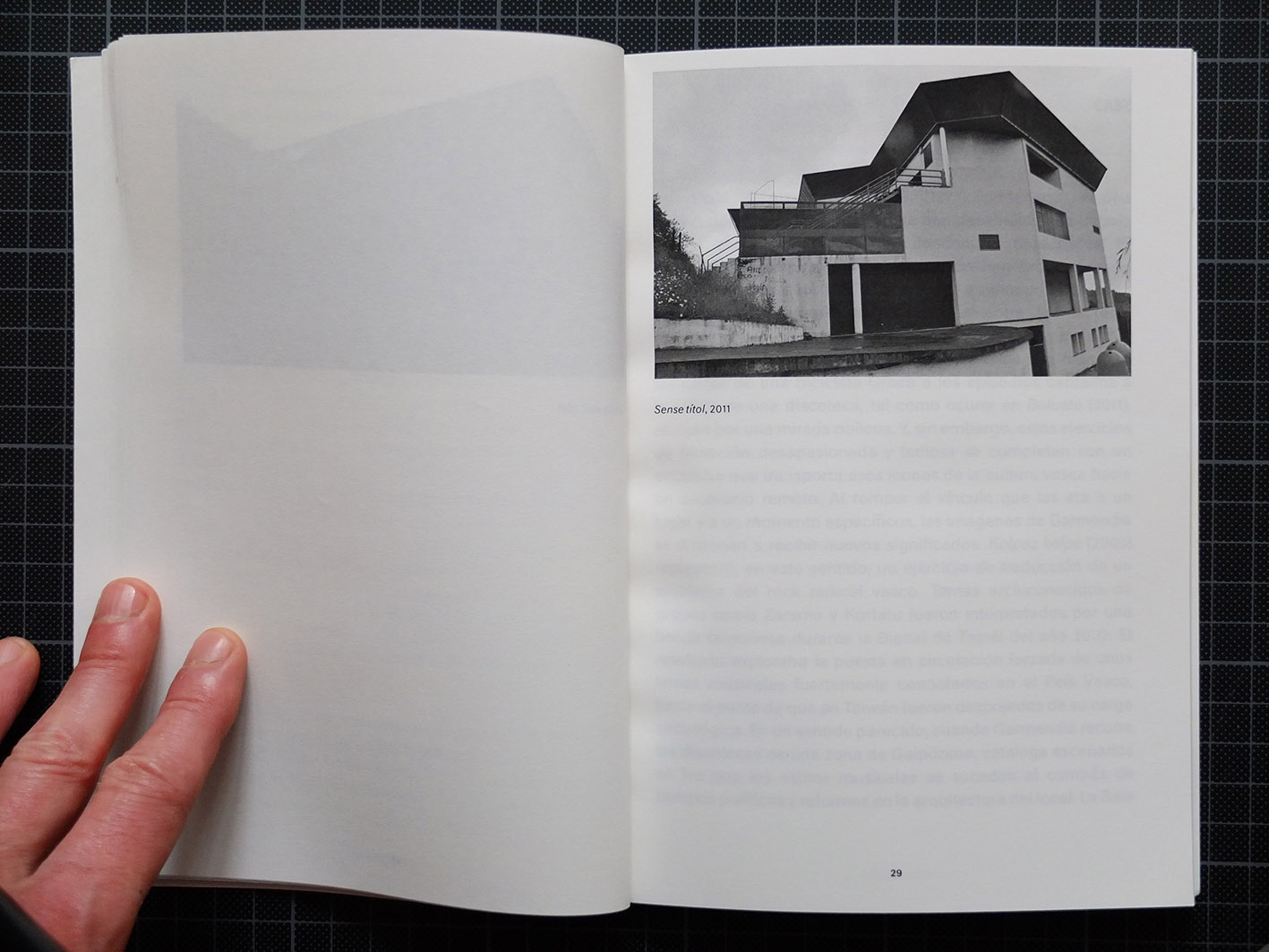

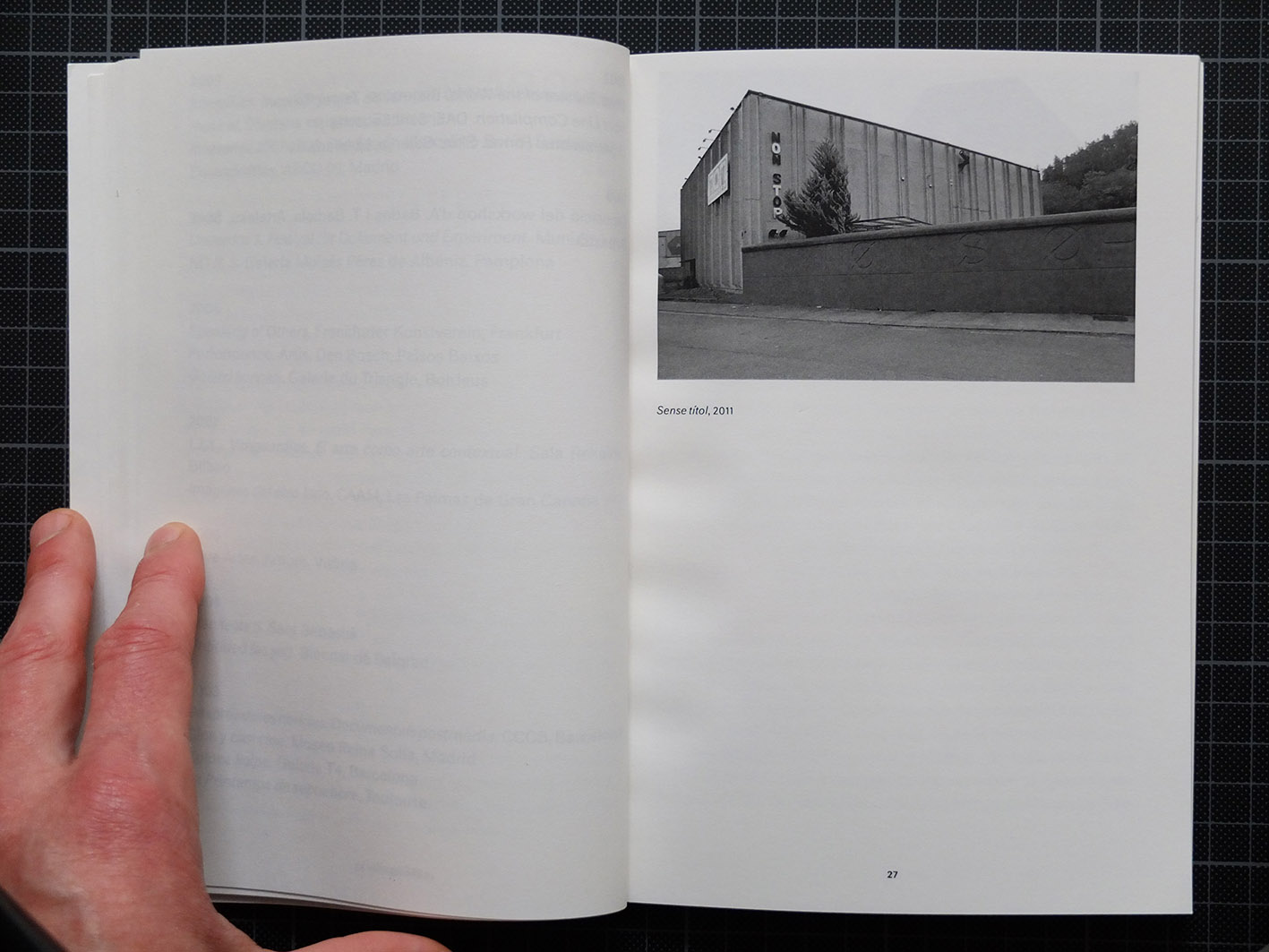

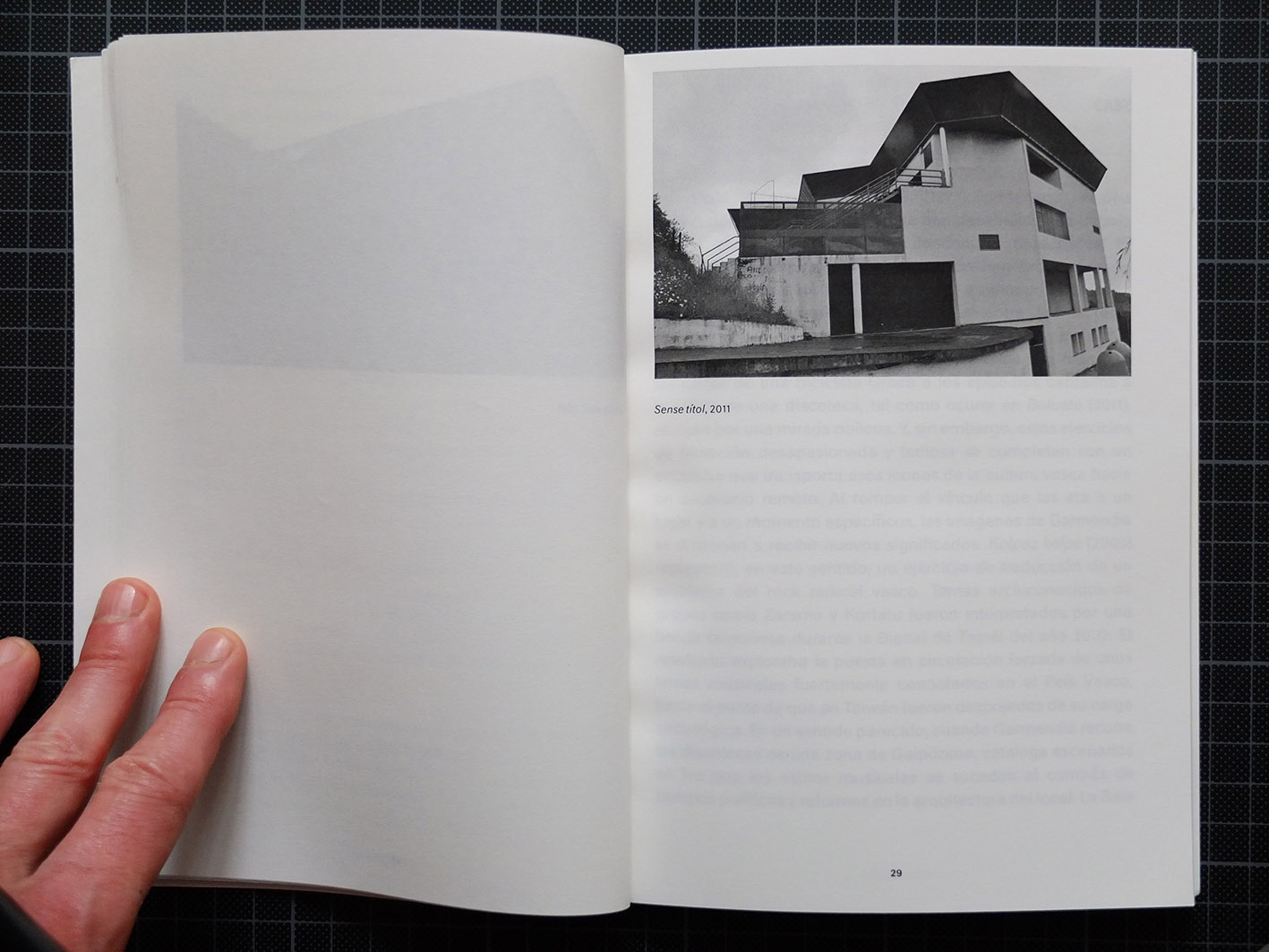

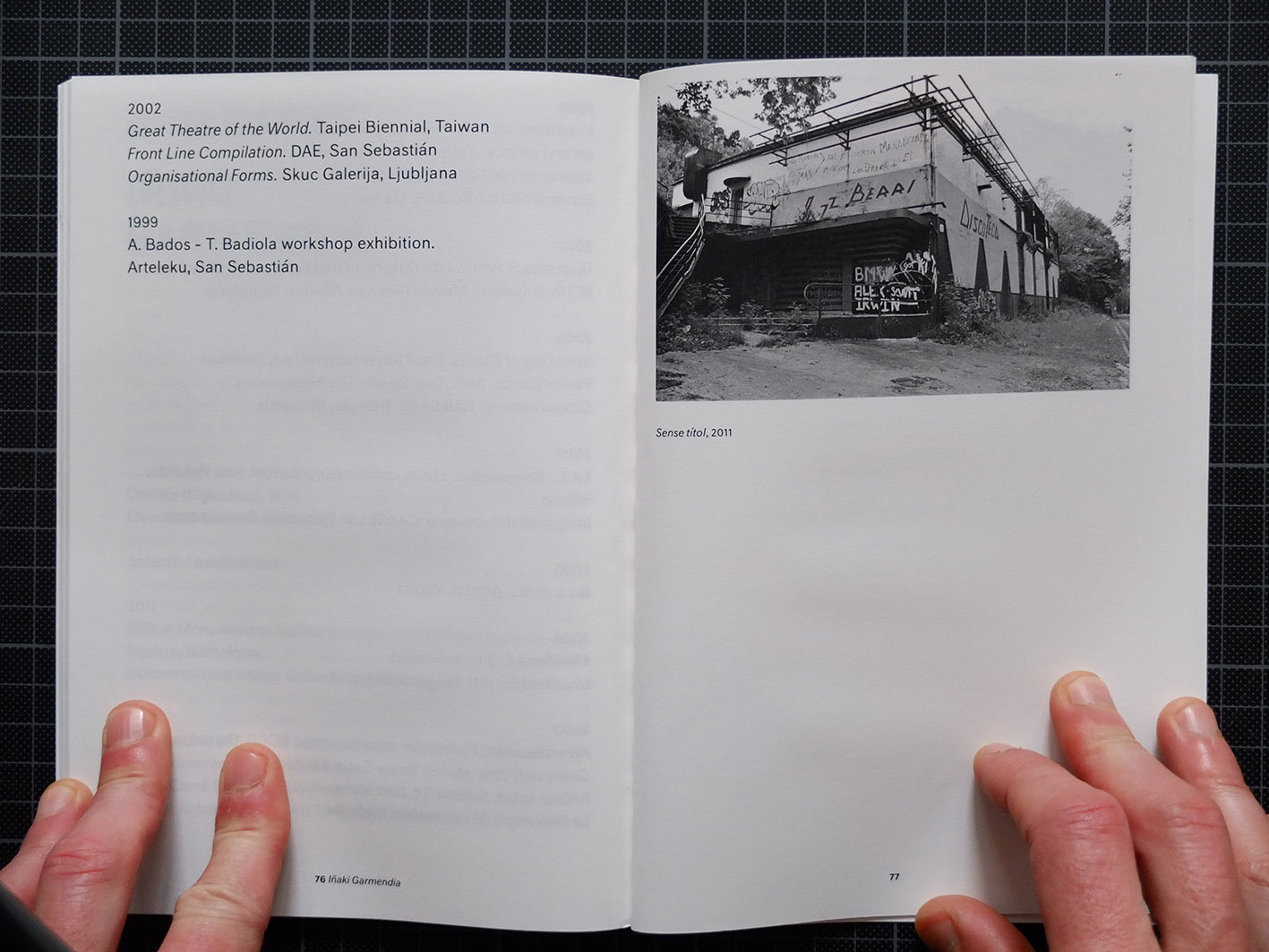

The camera makes itself evident with fast zoom-ins on the group, who try to enter Chalet 1 through the gate and windows. They look into the camera and ask “Do you have a pen?”, to which Iñaki replies: “No!”. The crumbling property is not displayed in its entirety. The camera, from a distance, frames all possible points of access. A platform rising on one side defines the entrance area, where they stay for most of the time. A number of elements structure the framing: dark green shutters on white, undecorated walls. A part for the whole a house in the rationalist strand of the “neo-Basque” style, a pastiche projected from the early 30s as an archetype of the bourgeoisie. The garden is unkempt, but the house is tightly locked. US vs THEM. US in the scene, THEM out of it. Time draws on in the entrance to the house in the late 90s, at the threshold between US and THEM. At this, a double portrait, subject and object are part of the representation in equal measure. They sit, smoke, talk, forget why they are there. Basque and Spanish become a murmur and blend into the location’s sound. The image blurs when the voice behind the camera interrupts them again. They have to keep trying to break in. It starts to rain again, and they leave.

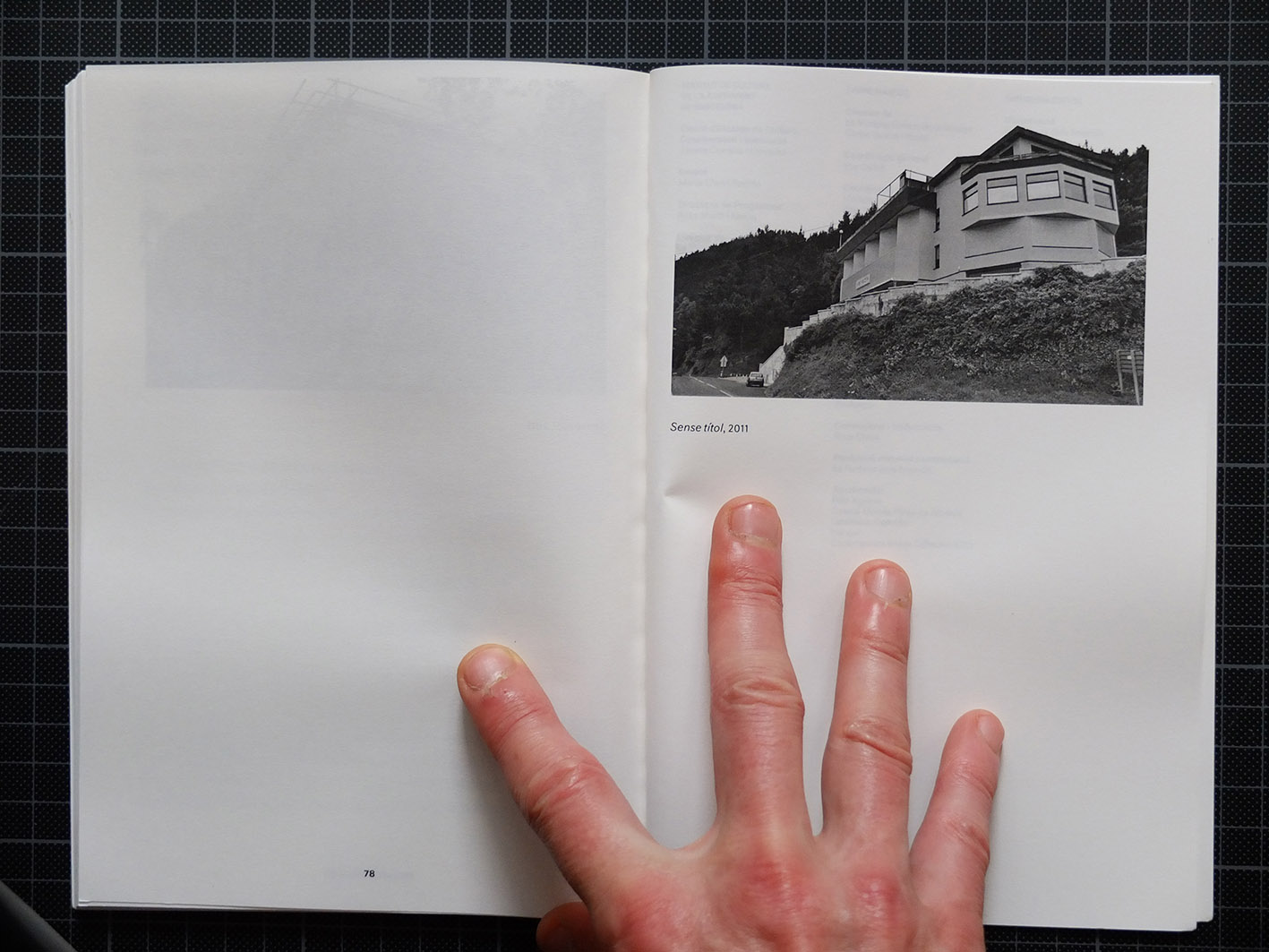

The group steps out of the car again. Now they enter another empty house. They soon access the interior, through the first floor balconies and windows. Once again, only the parts: a brick façade with curved angles, large windows, some of them of whimsical circular forms, dark wood —iroko or tali—, mark the style’s evolution through time. Another variant of the Basque repertoire, resembling organic architecture from the mid-twentieth century. The group navigates the property, penetrating its nooks and crannies. The scene, a static shot, flows like a composition between the decisions and interests of each individual. House number 2 could have been built in the late 60s or early 70s. It is now abandoned, but in perfect condition. Perhaps THEY fled somewhere safer. Once inside, in one of the rooms, the group goes through the notes together. Iñaki’s presence in the image clearly shows that the action concerns a planned structure, but even then, we are not capable of delimiting it clearly. They walk in circles, naturally, as if they moved through the space on a skateboard in slow motion. They run across the room, the sound is deafening. THEY cannot hear them.

Related bibliography

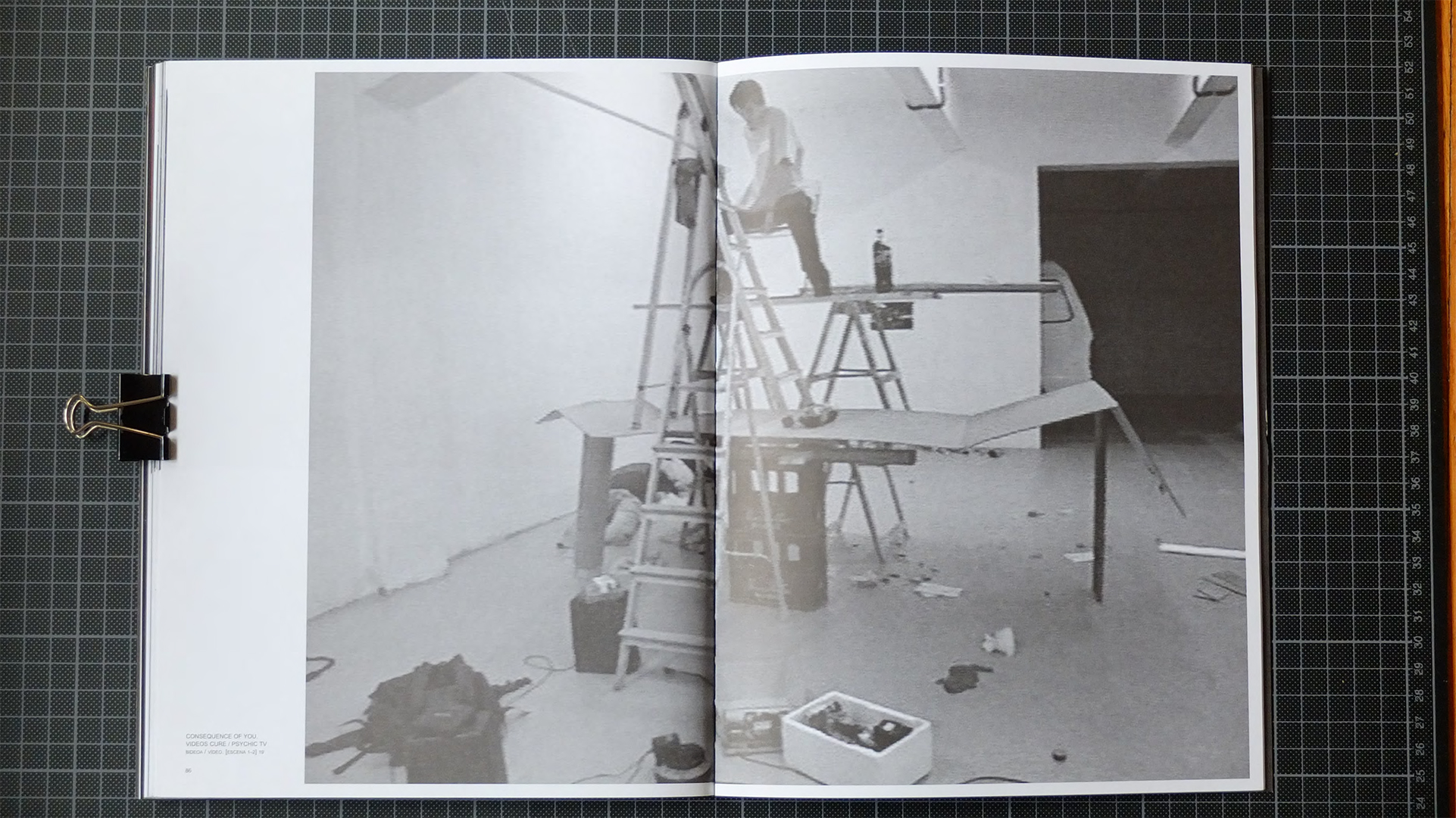

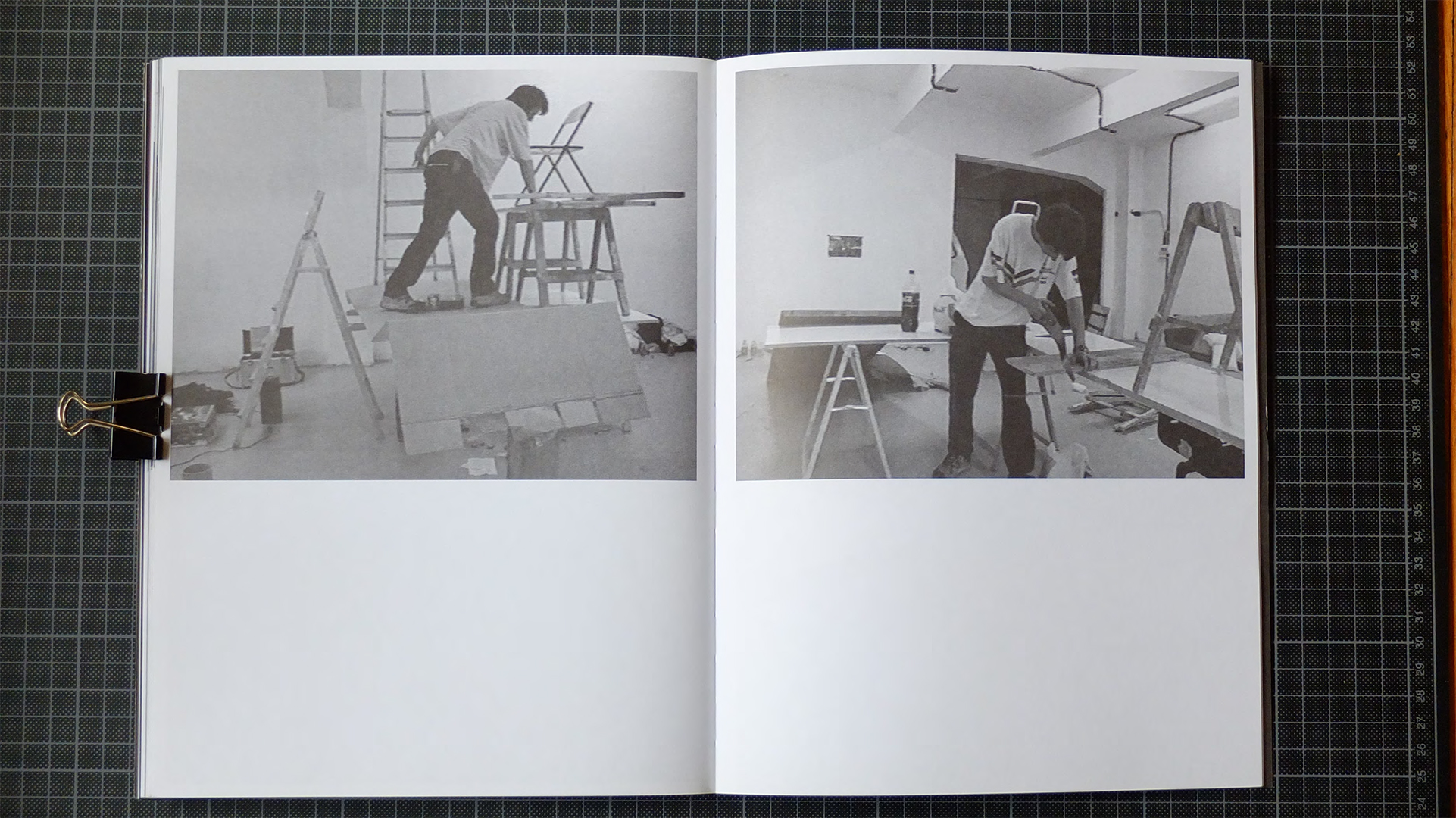

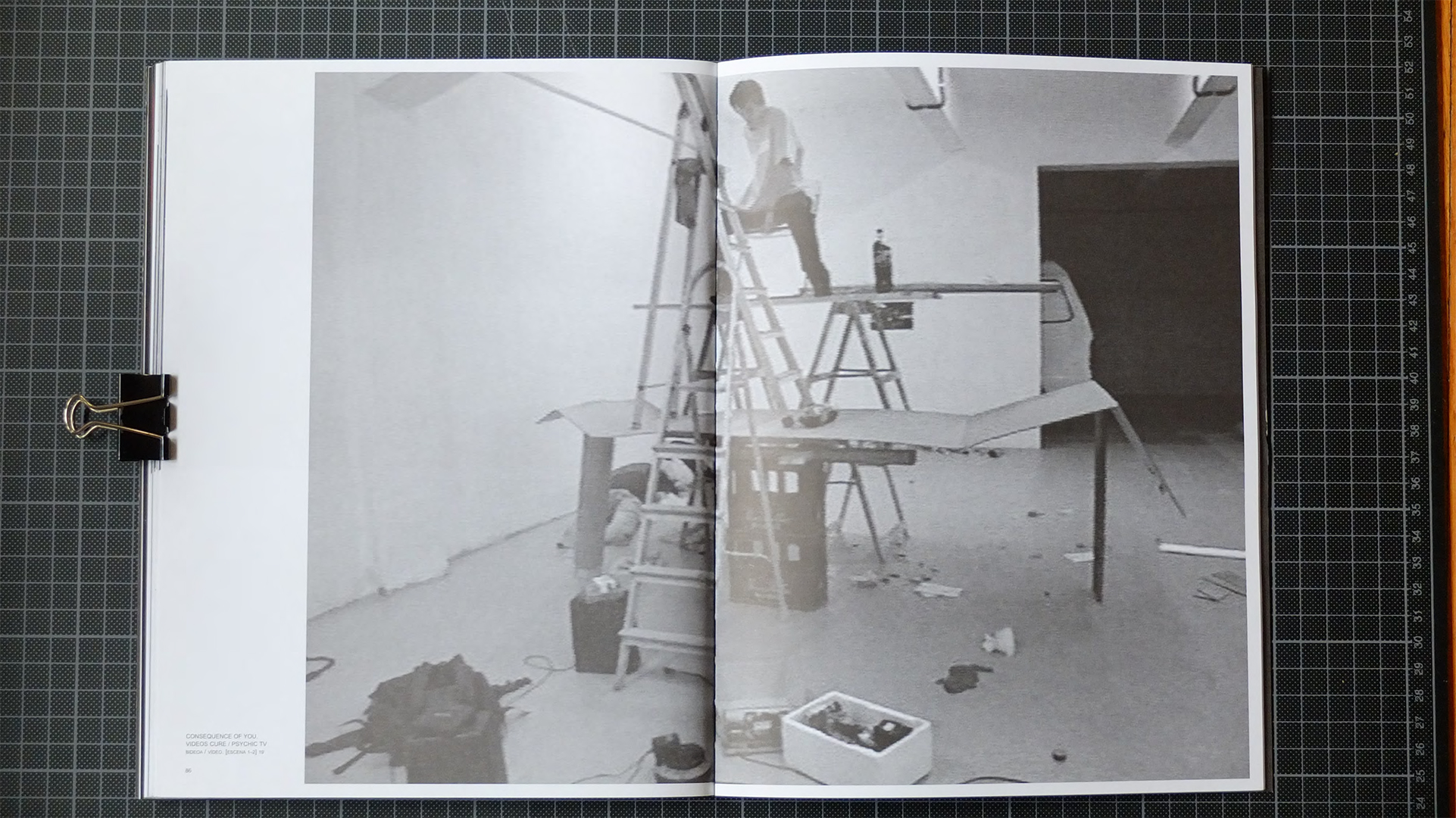

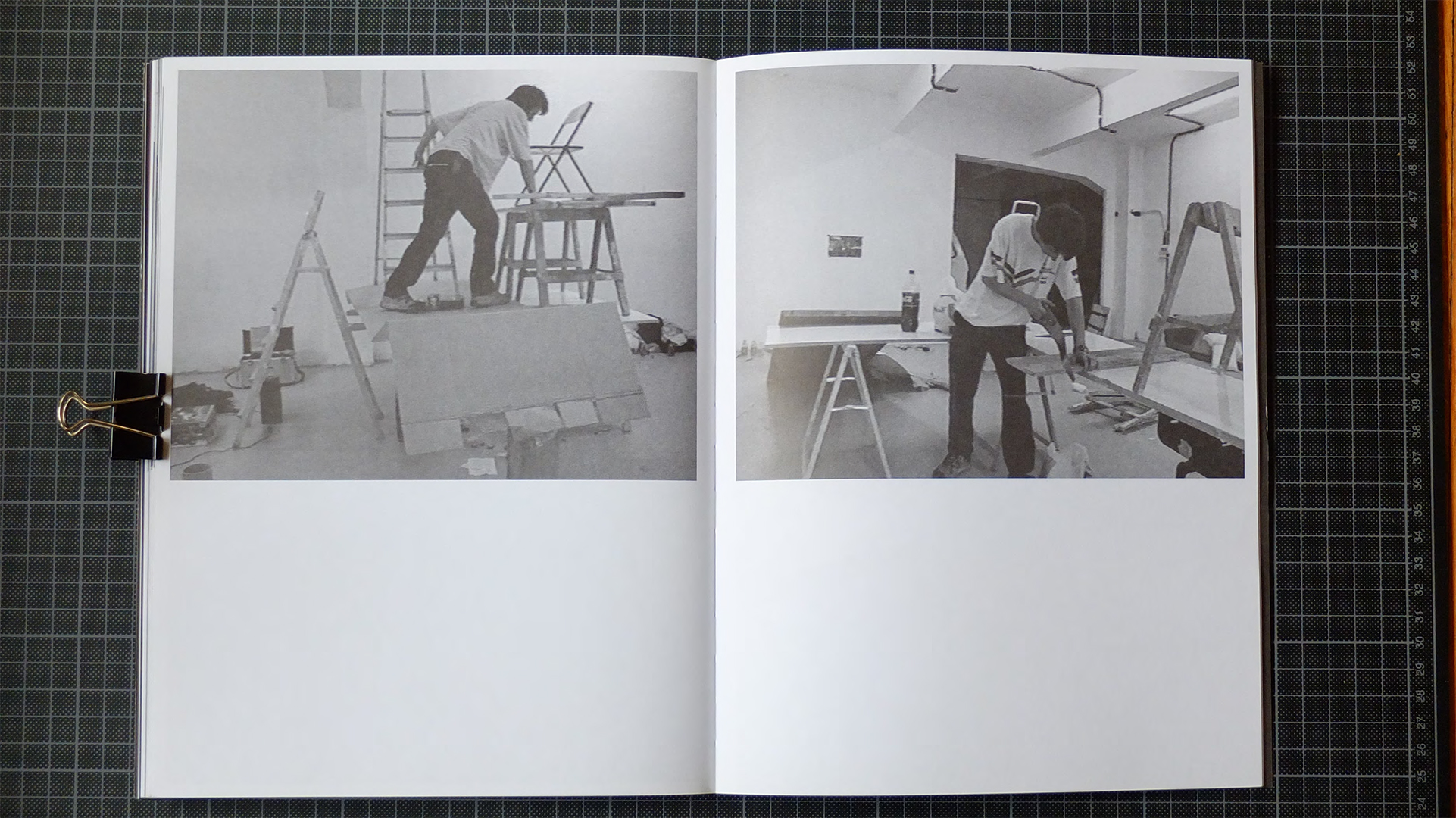

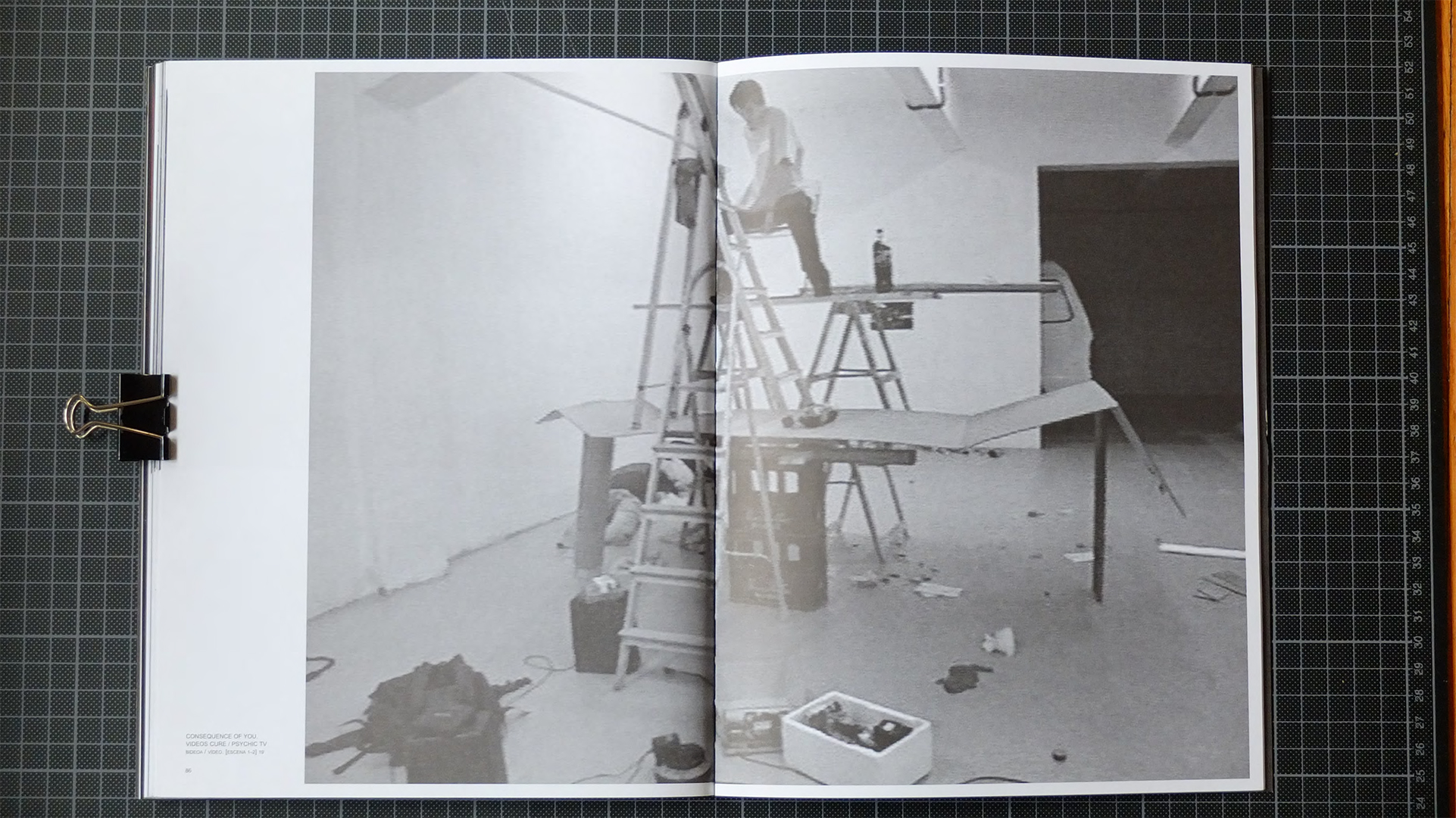

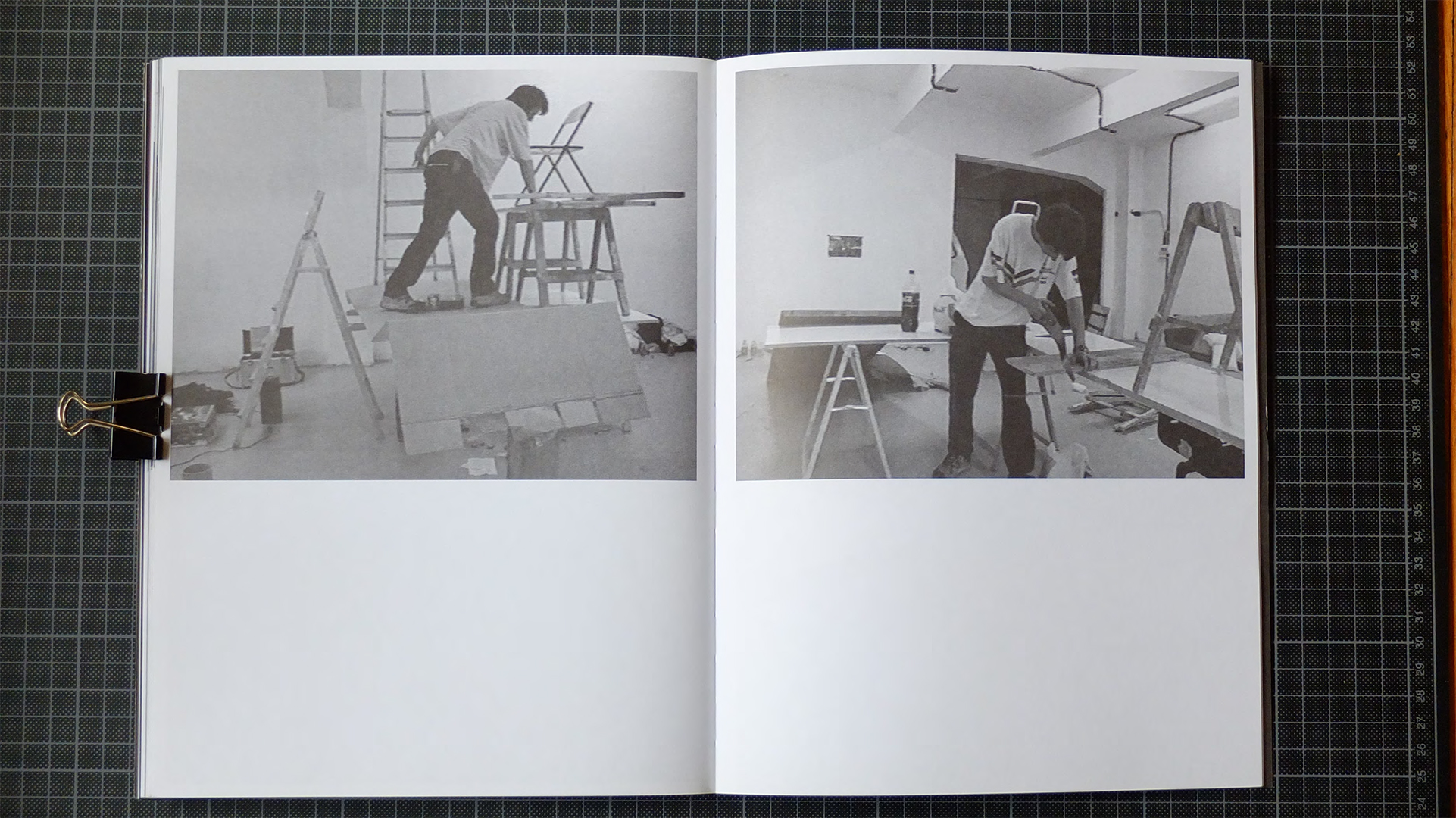

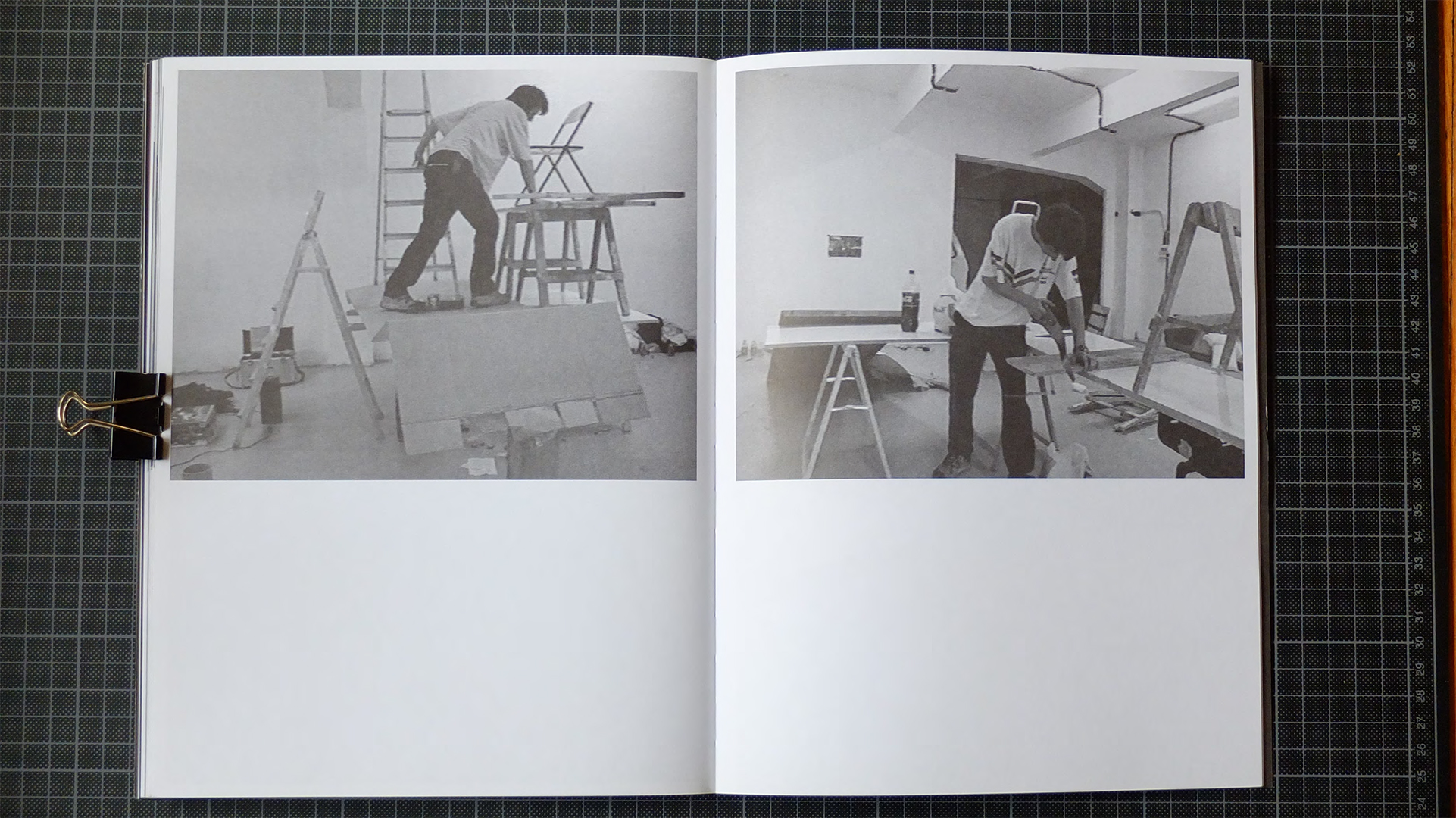

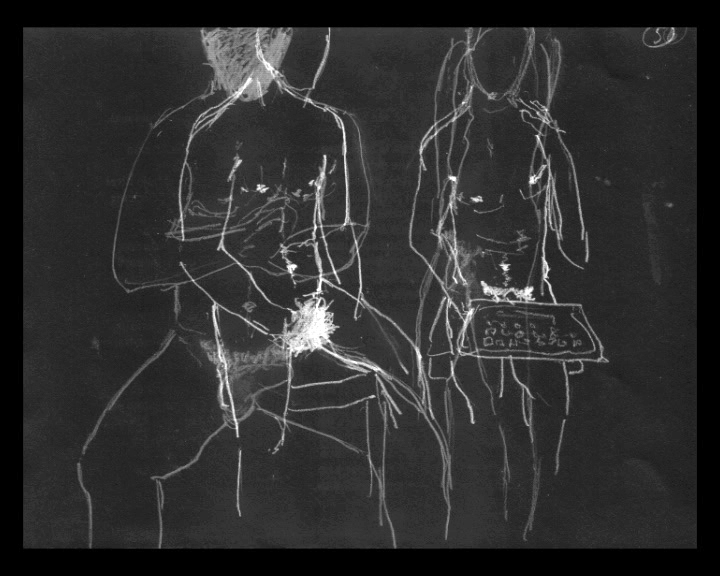

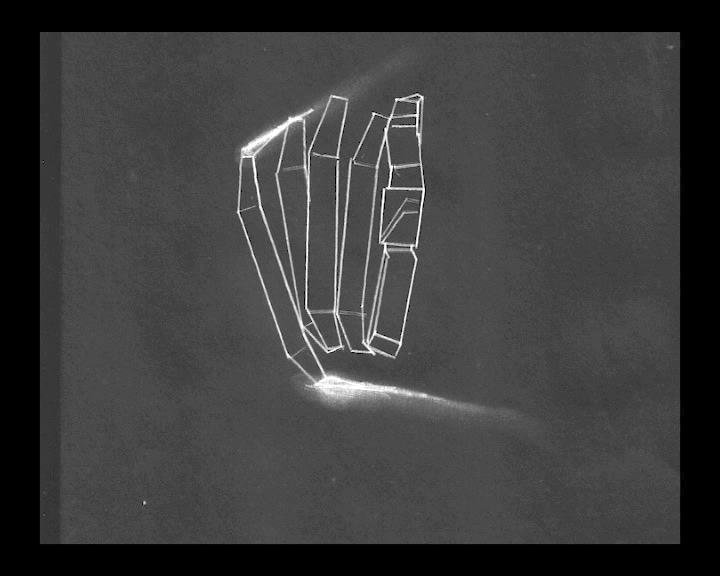

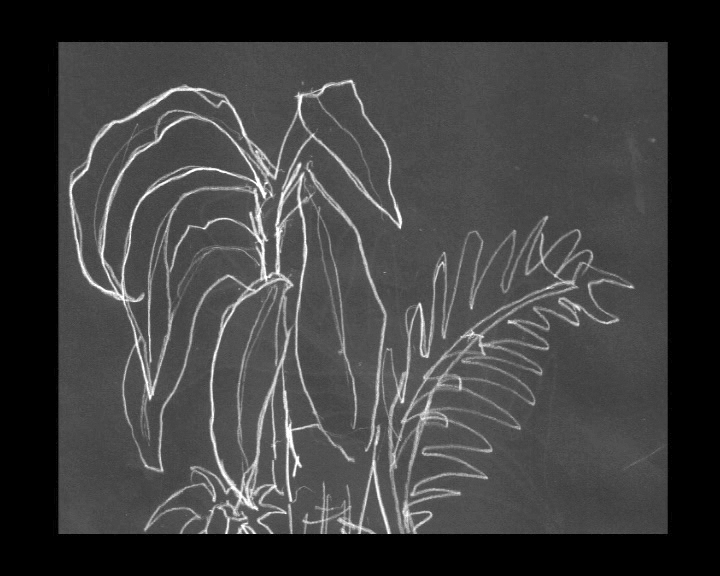

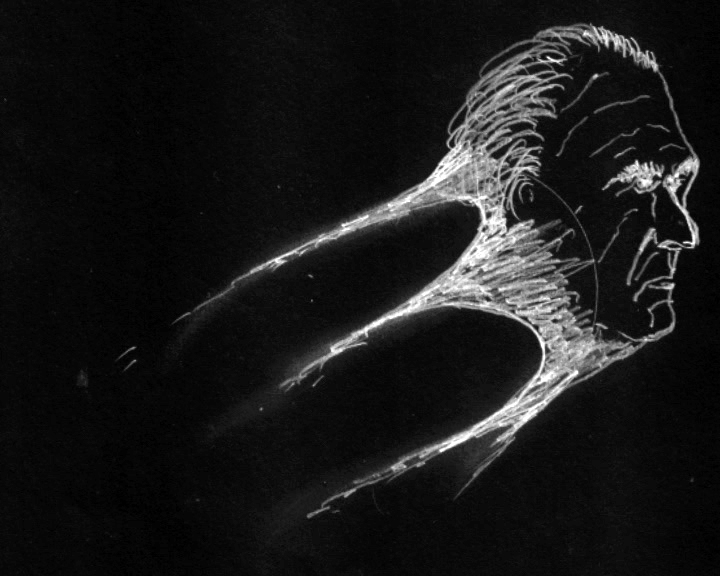

Exhibition views of Me voy a ir, me voy, estoy ido . Donostia-San Sebastián, DAE-Donostiako Arte Ekinbideak : Egiako Kultur Etxea = Casa de Cultura de Egia, May 28 – JUne 26, 1999.

Images courtesy of DAE and Peio Aguirre.

→ Dark-Drunker-Rocket. Barcelona, Centre d’Art Santa Monica, December 2006 – 4 March 2007.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

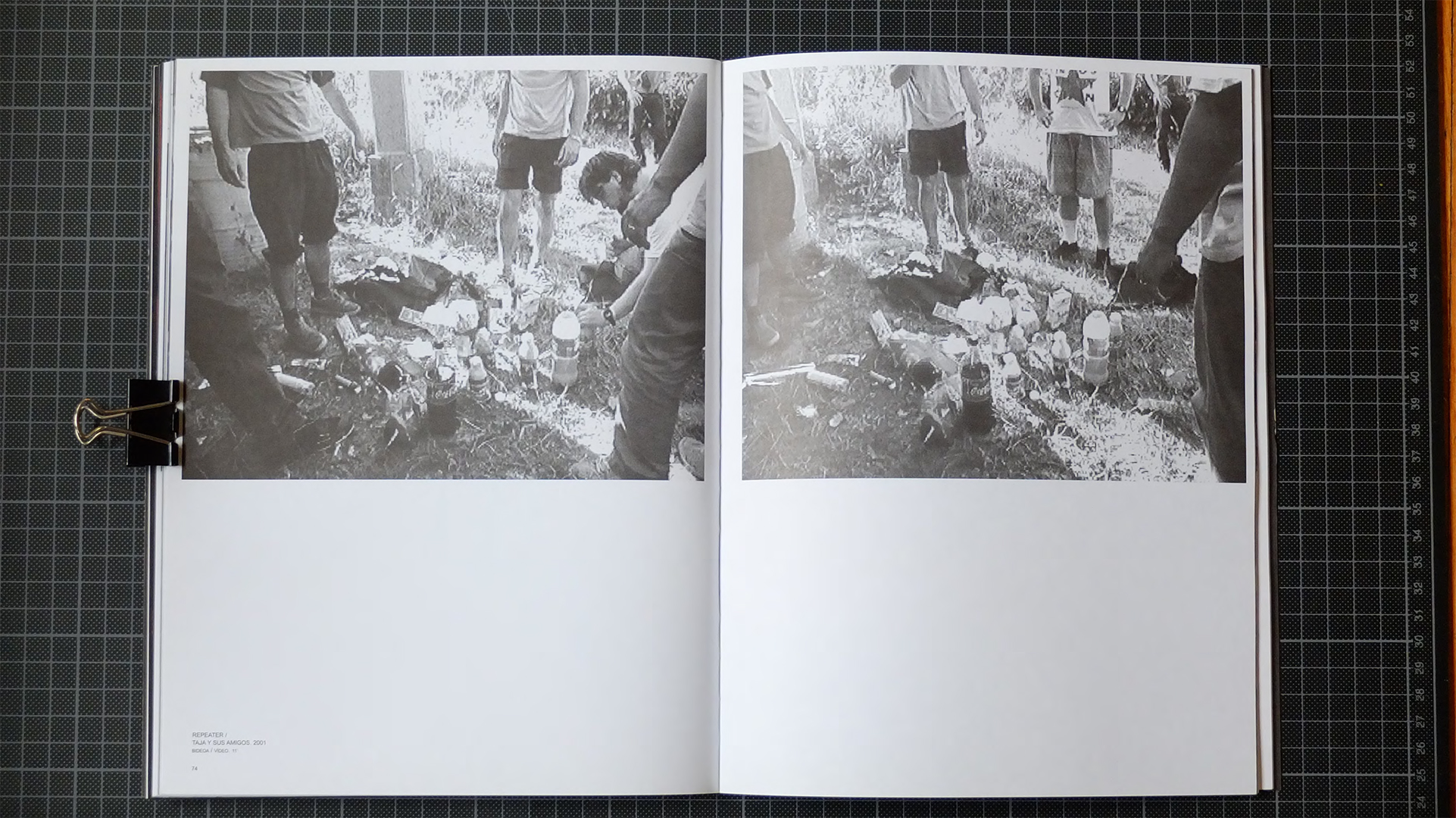

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

11’39’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

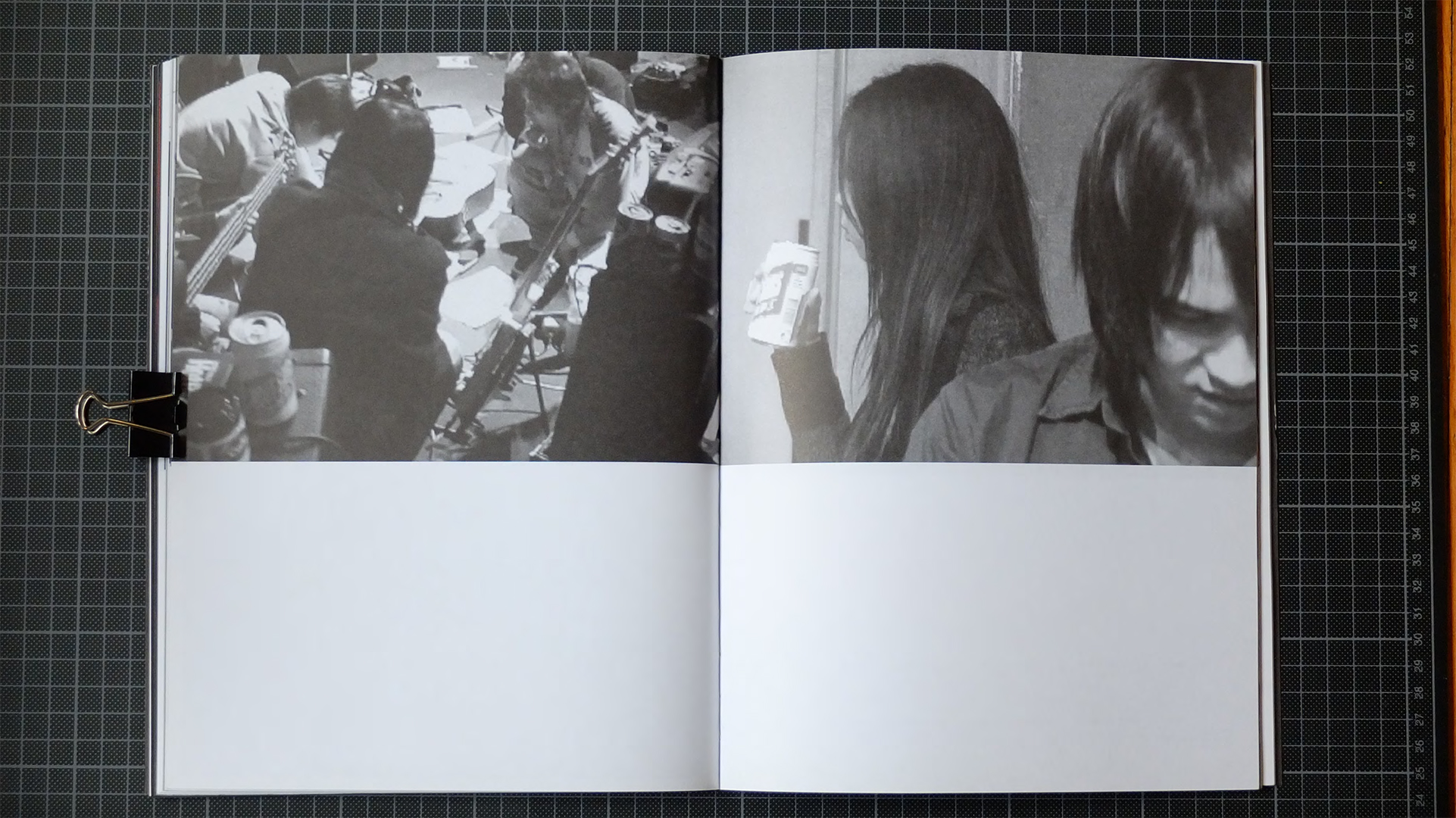

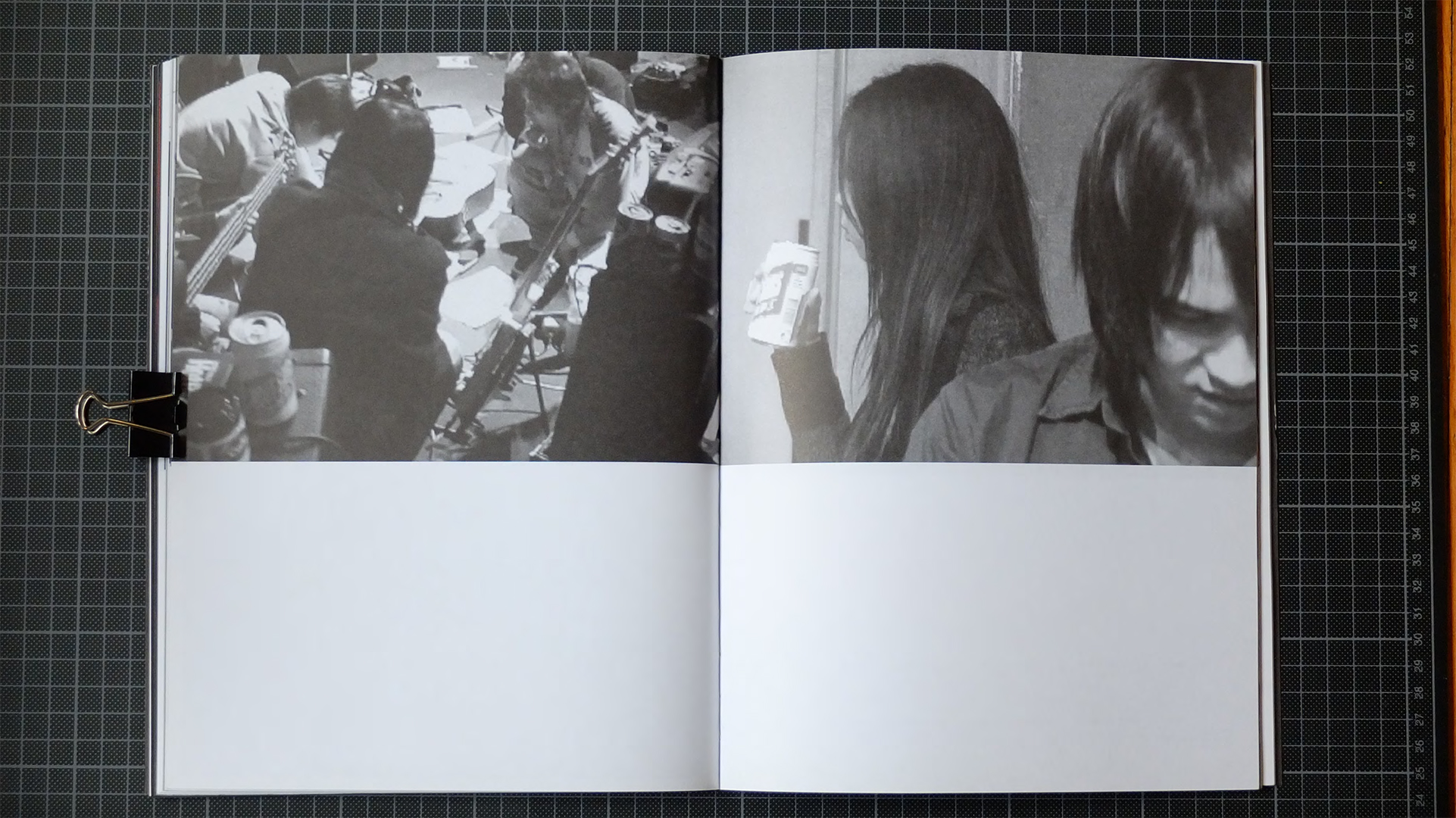

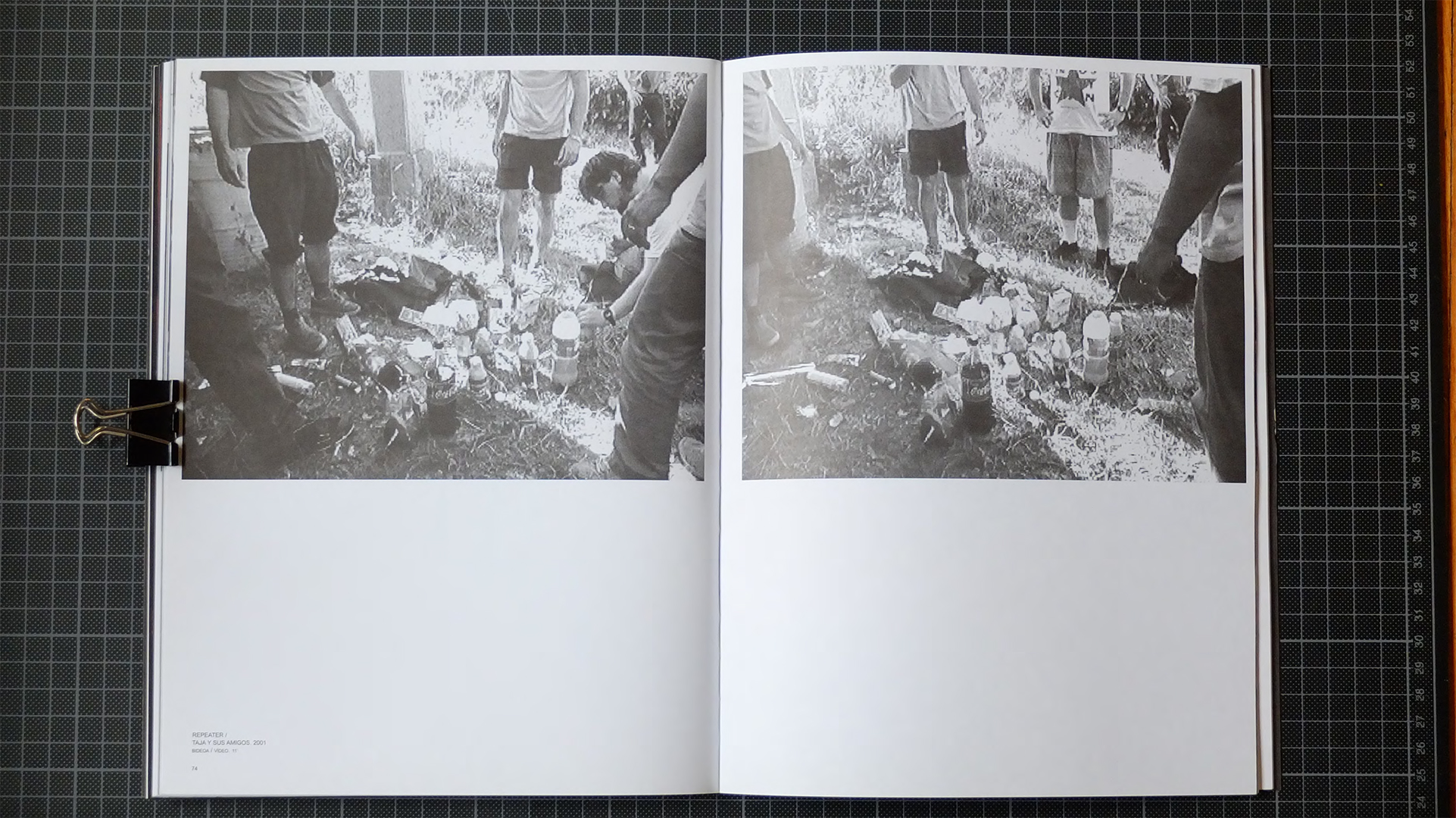

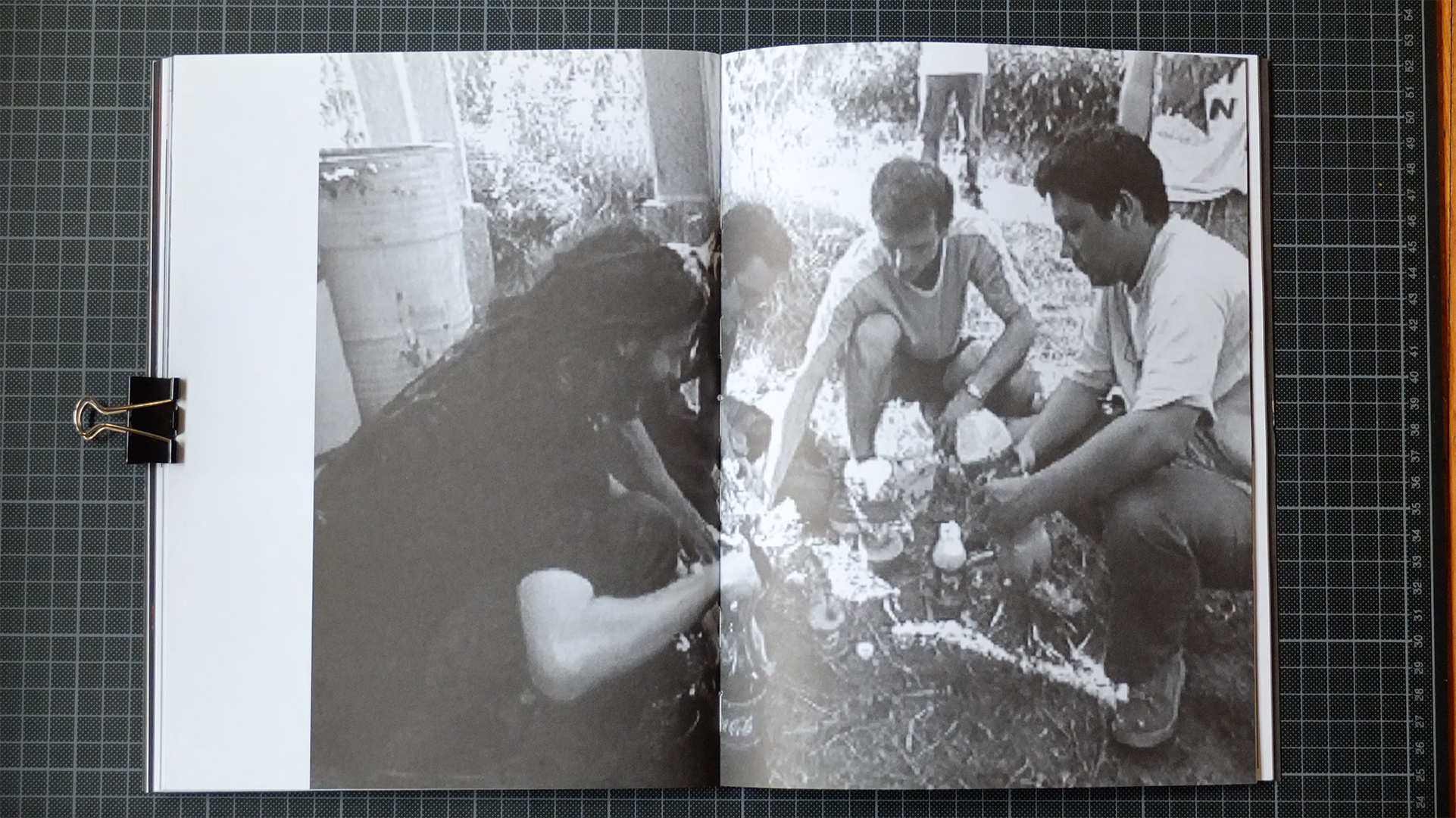

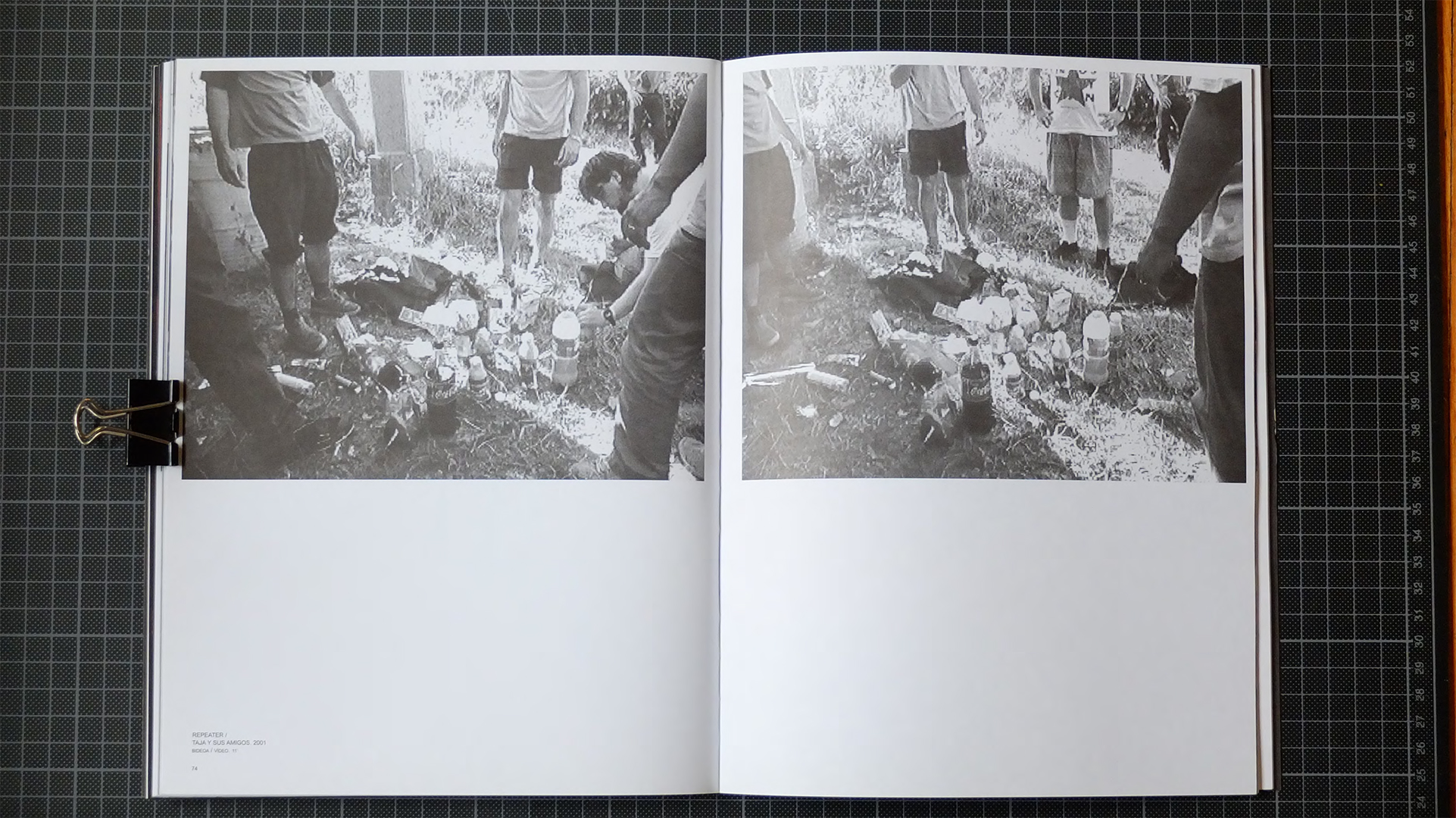

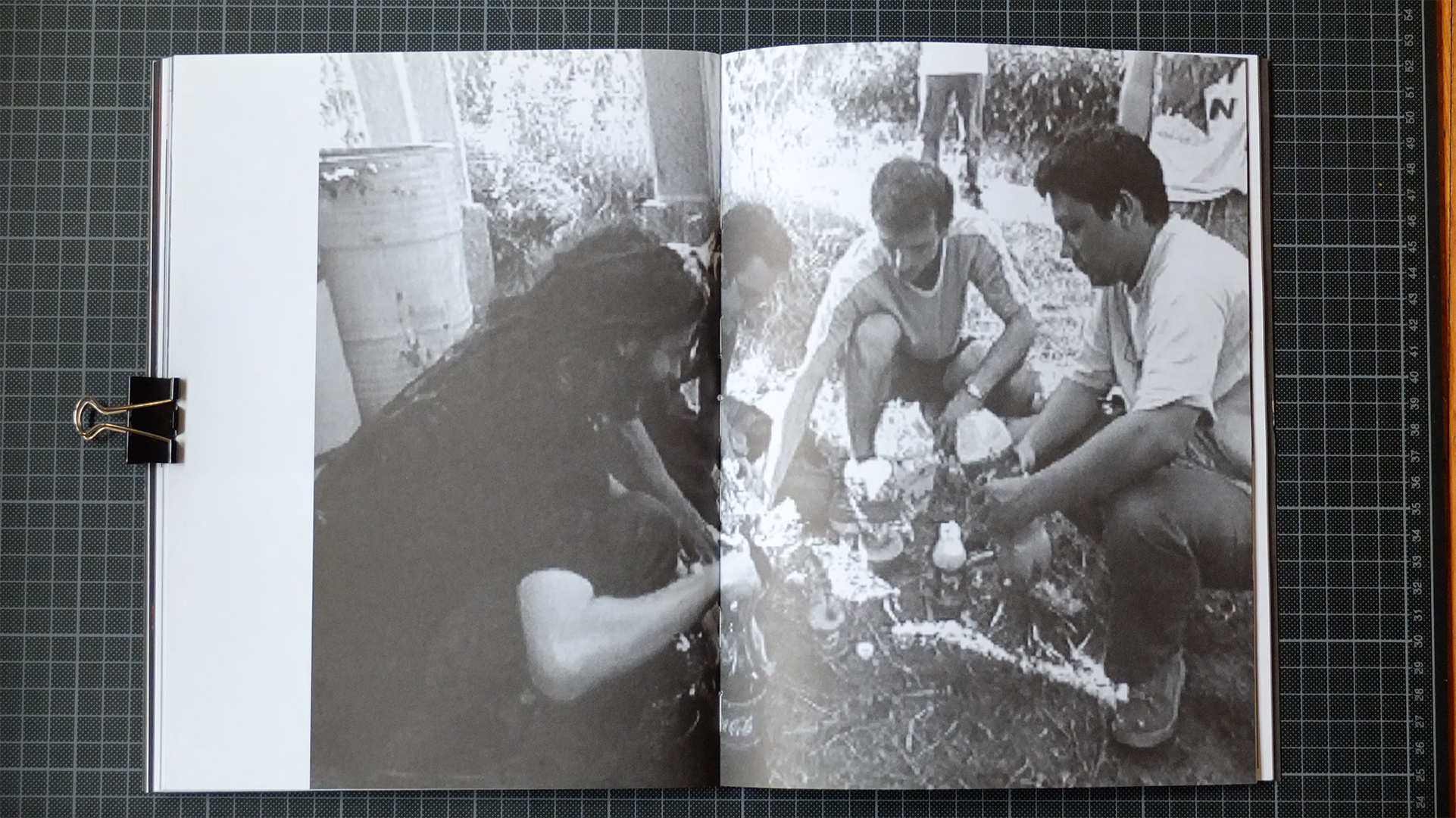

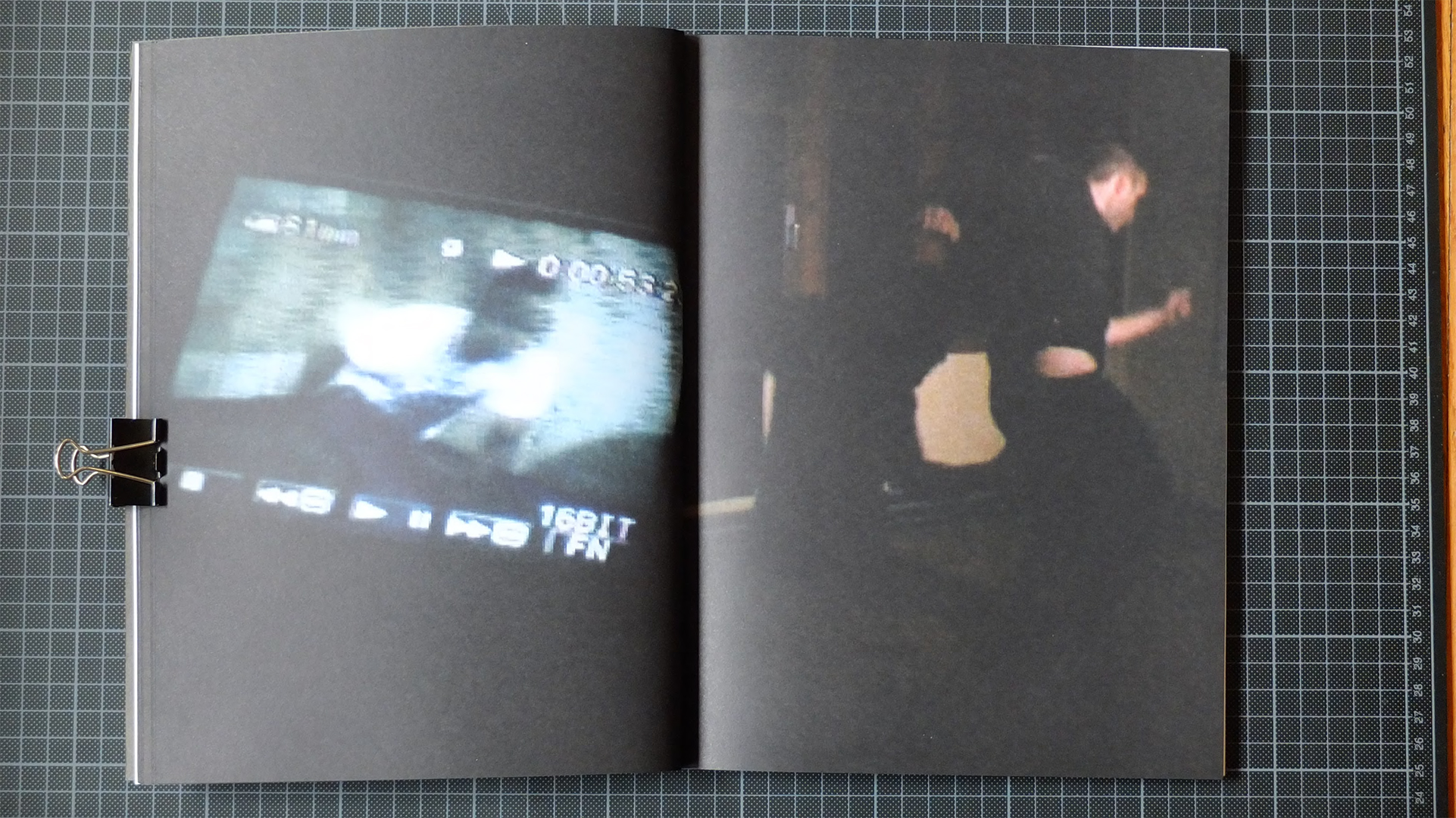

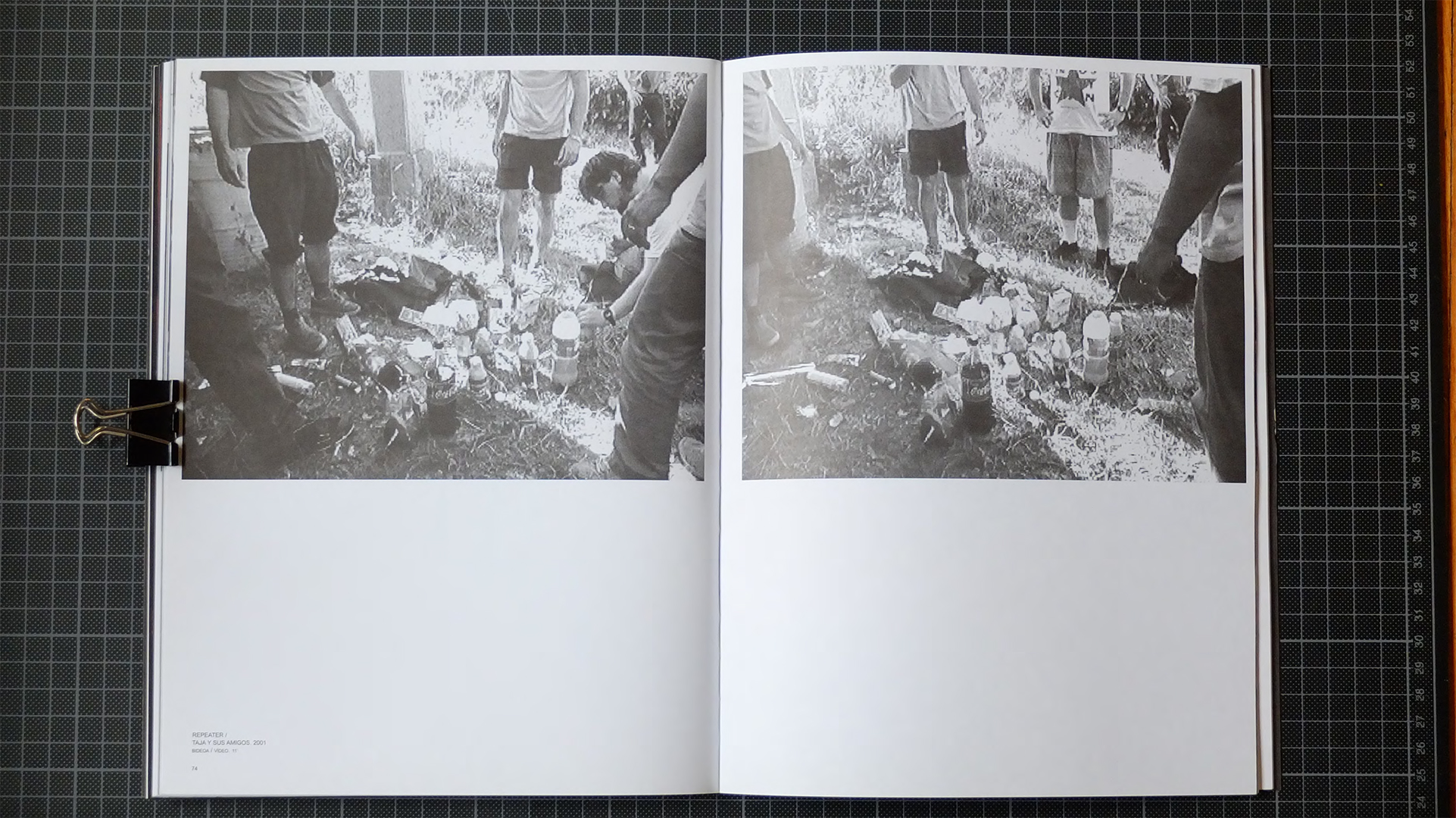

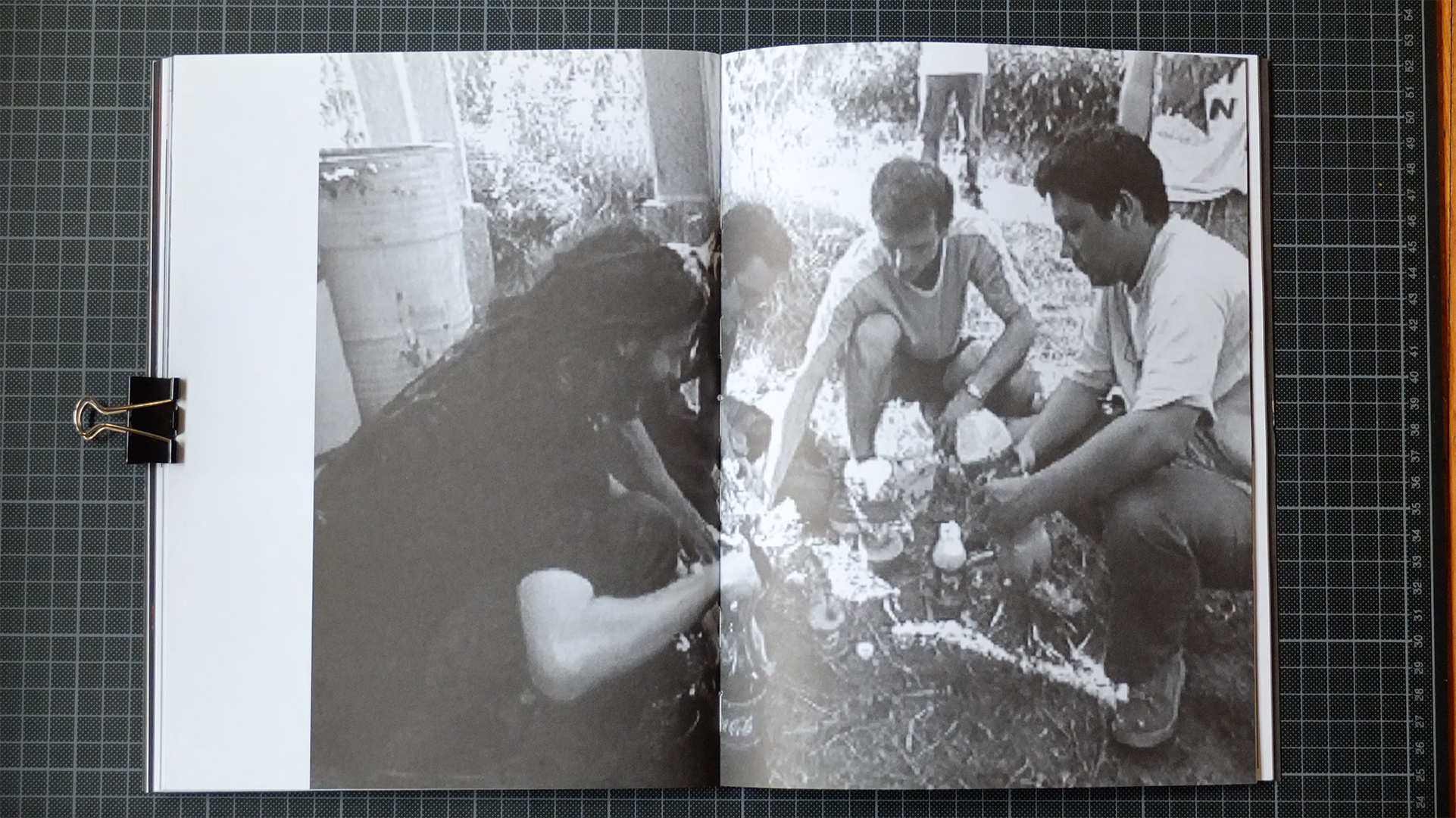

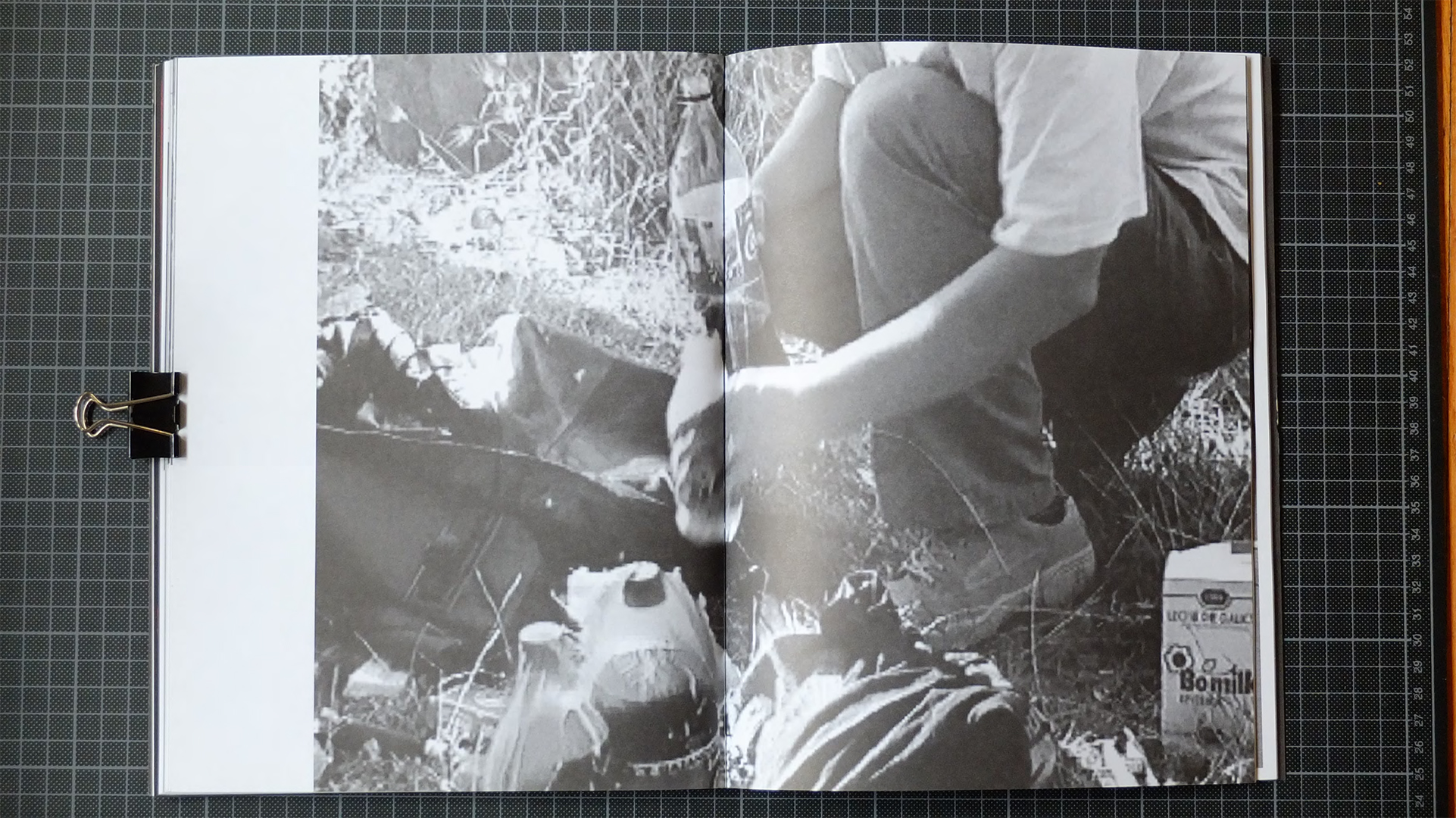

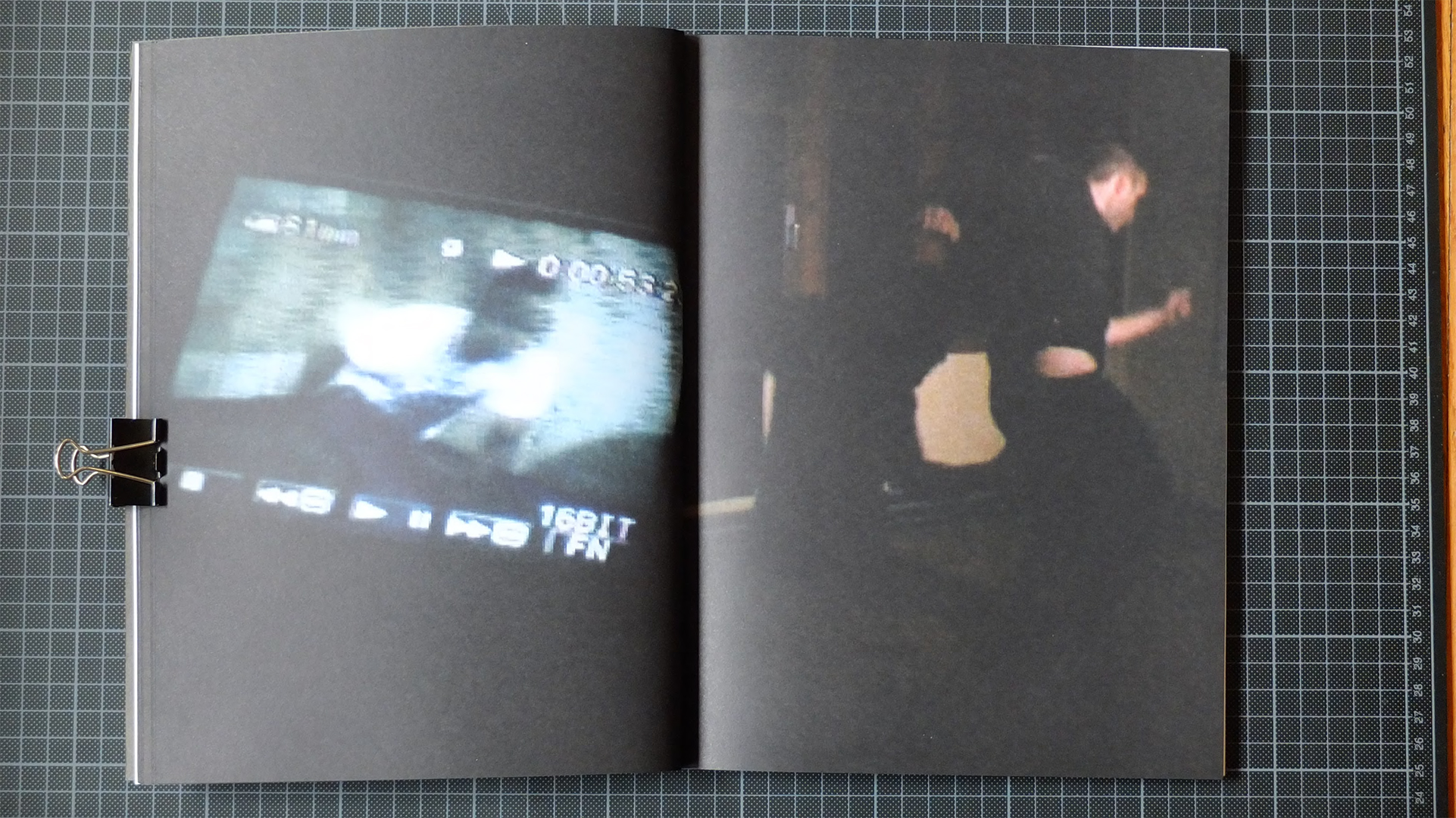

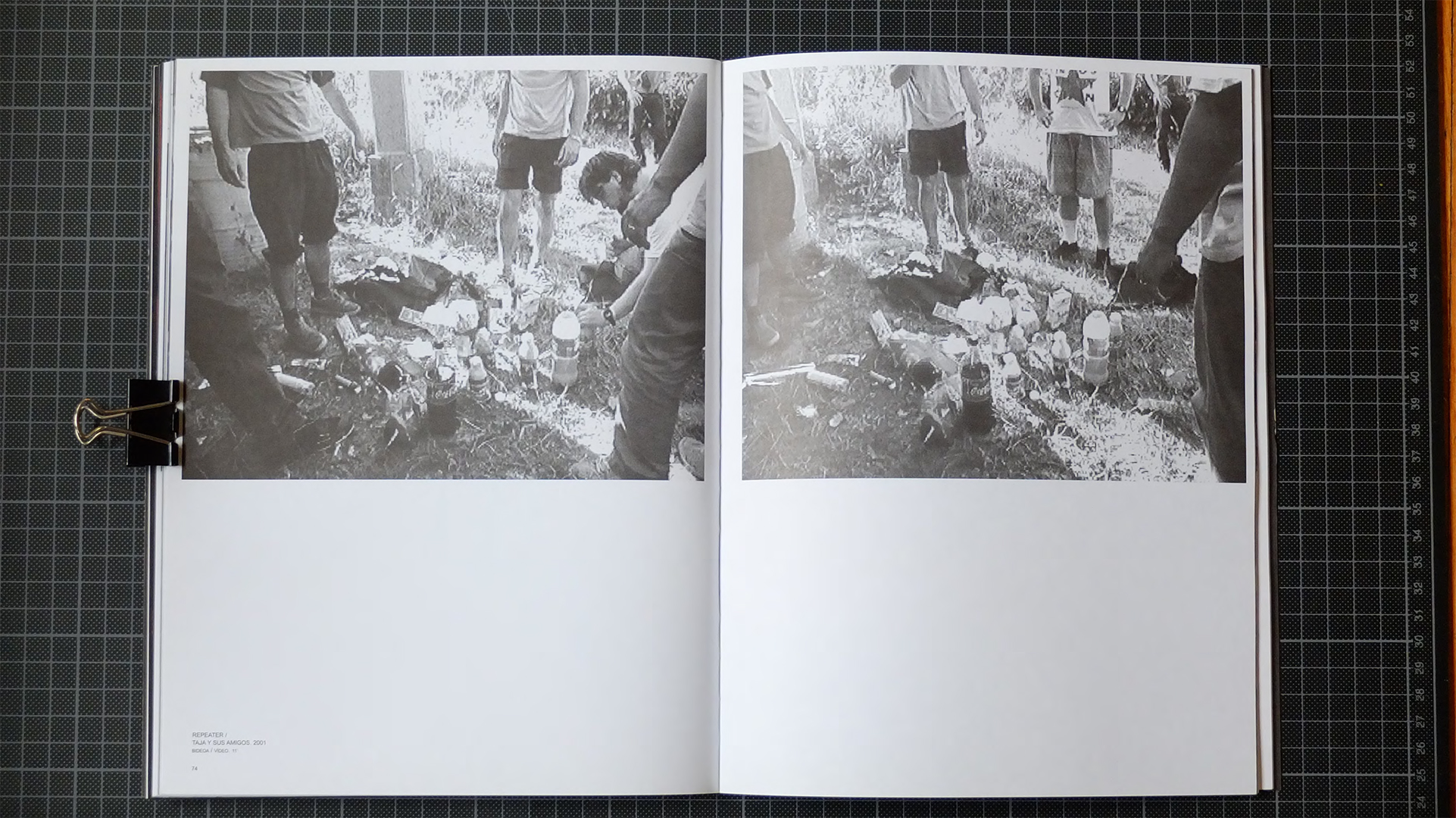

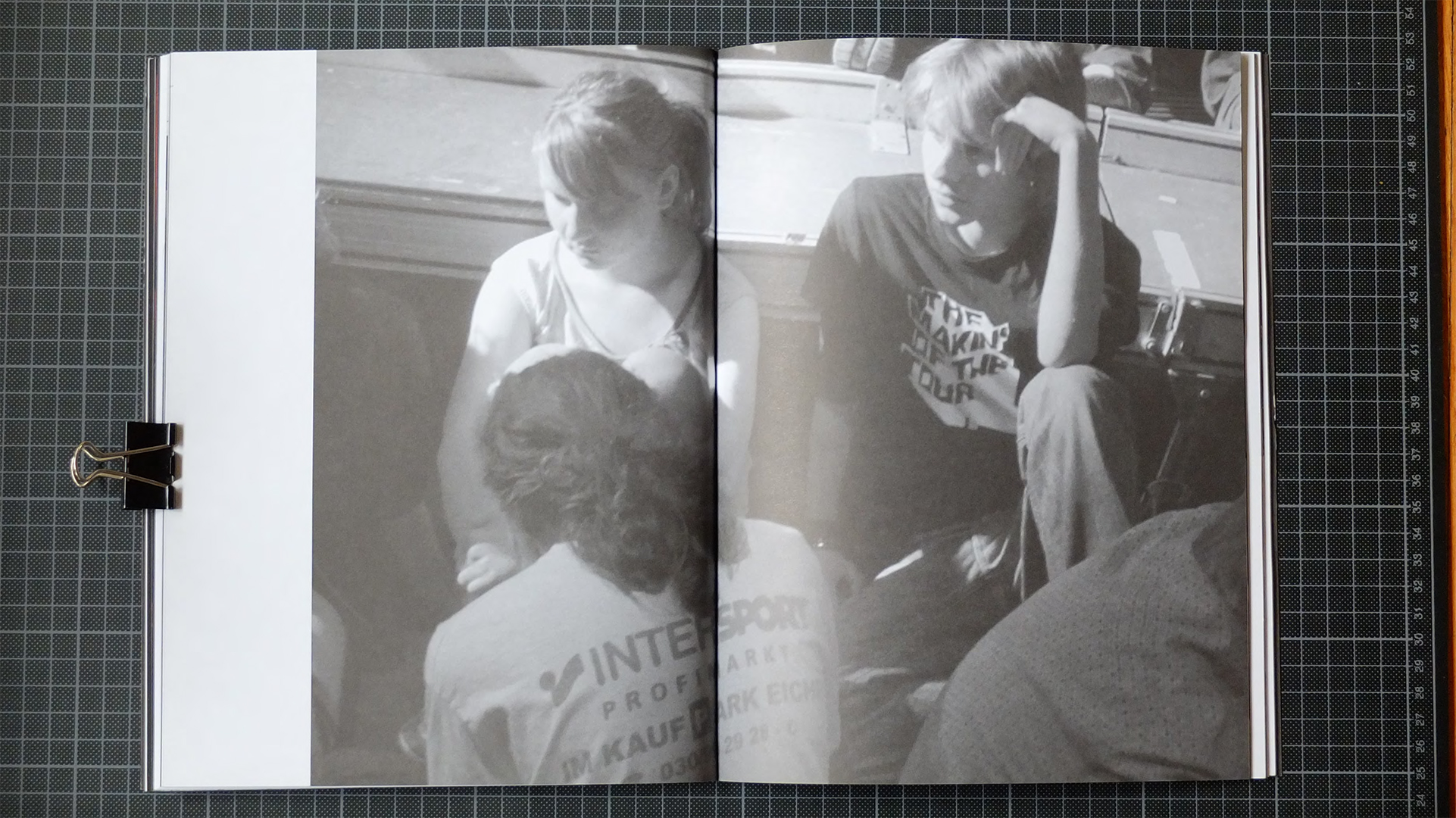

A “technical image”, as Vilém Flusser called it, is initiated at the meeting point between the lens, the eye, and the scene captured. The High 8 video camera used in Taja y sus amigos had no viewfinder, which made it necessary to connect it to a monitor in order to access the footage. This domestic procedure also made the editing of the recording possible with the help of a VHS player. This is how the editing was carried out—pressing rec and pause in order to connect the different takes.

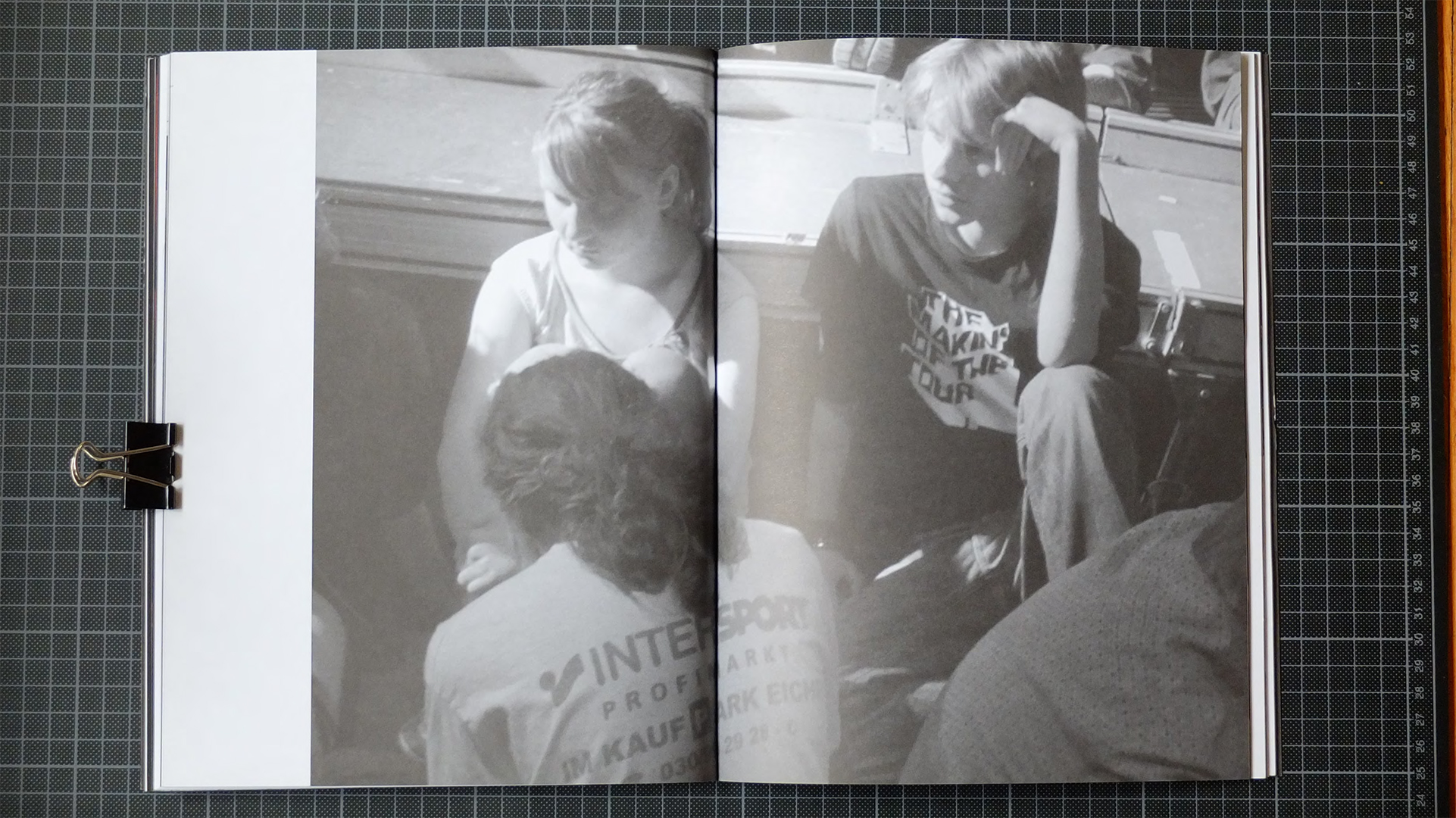

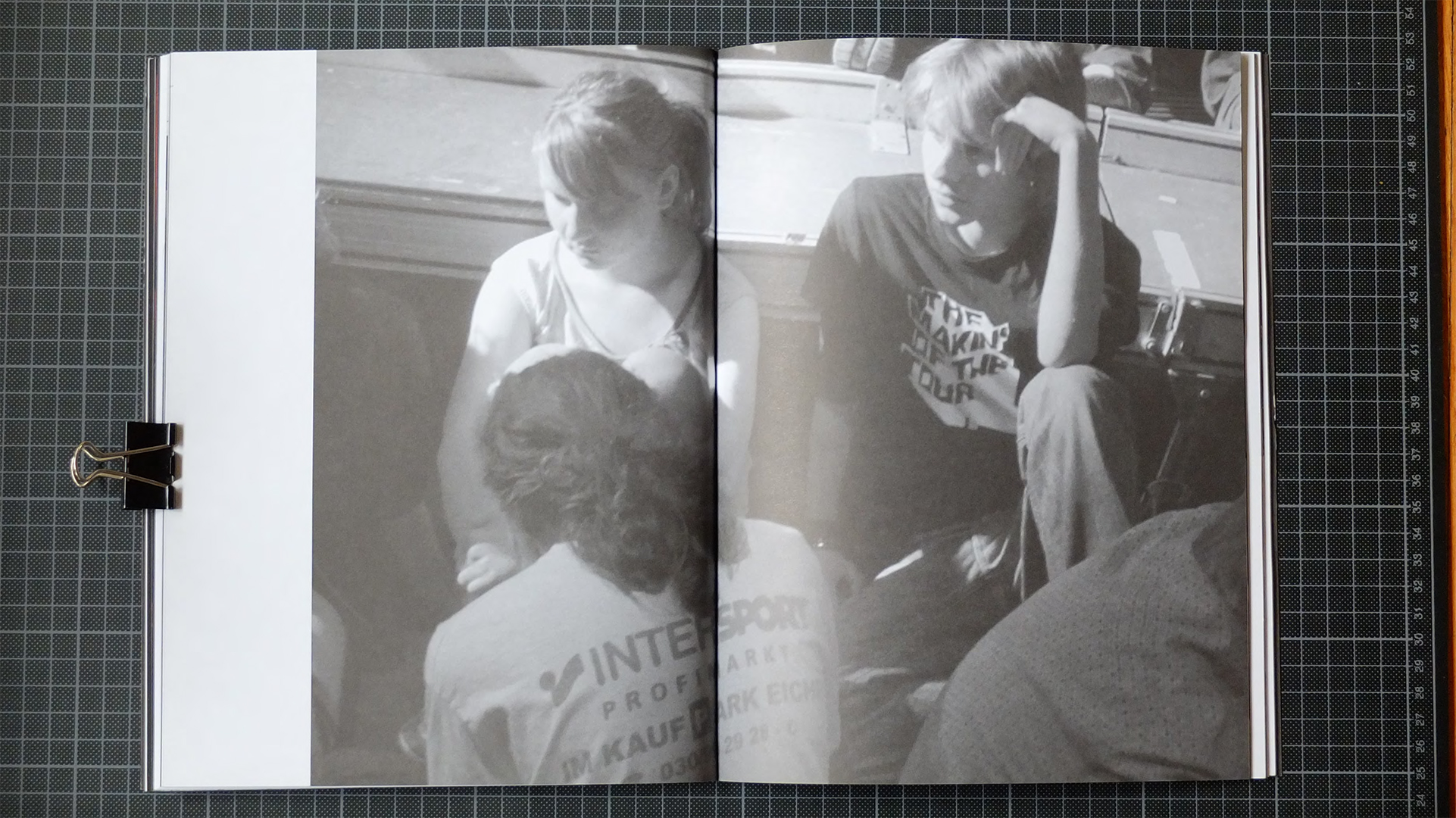

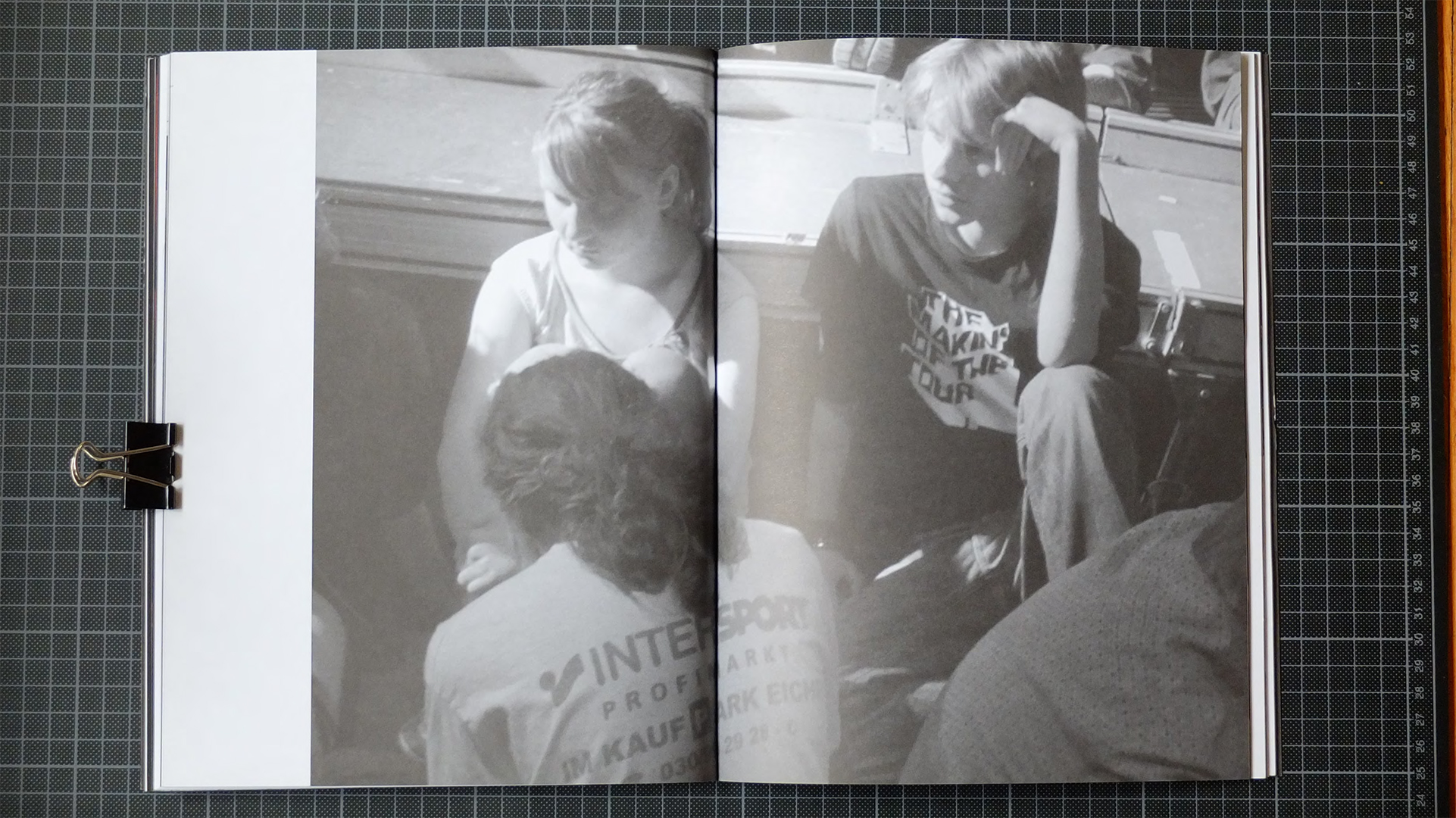

This video was finished in 2001, but the shooting was completed two years prior. I remember this when seeing some of the t-shirts, the battered dreadlocks sported by one of them —which he would soon cut off—, the thin frame of somebody else’s glasses. I remember the rehearsal room by the train tracks too, a summer afternoon, even though none of these elements were planned. They just happened, and happened to be there.

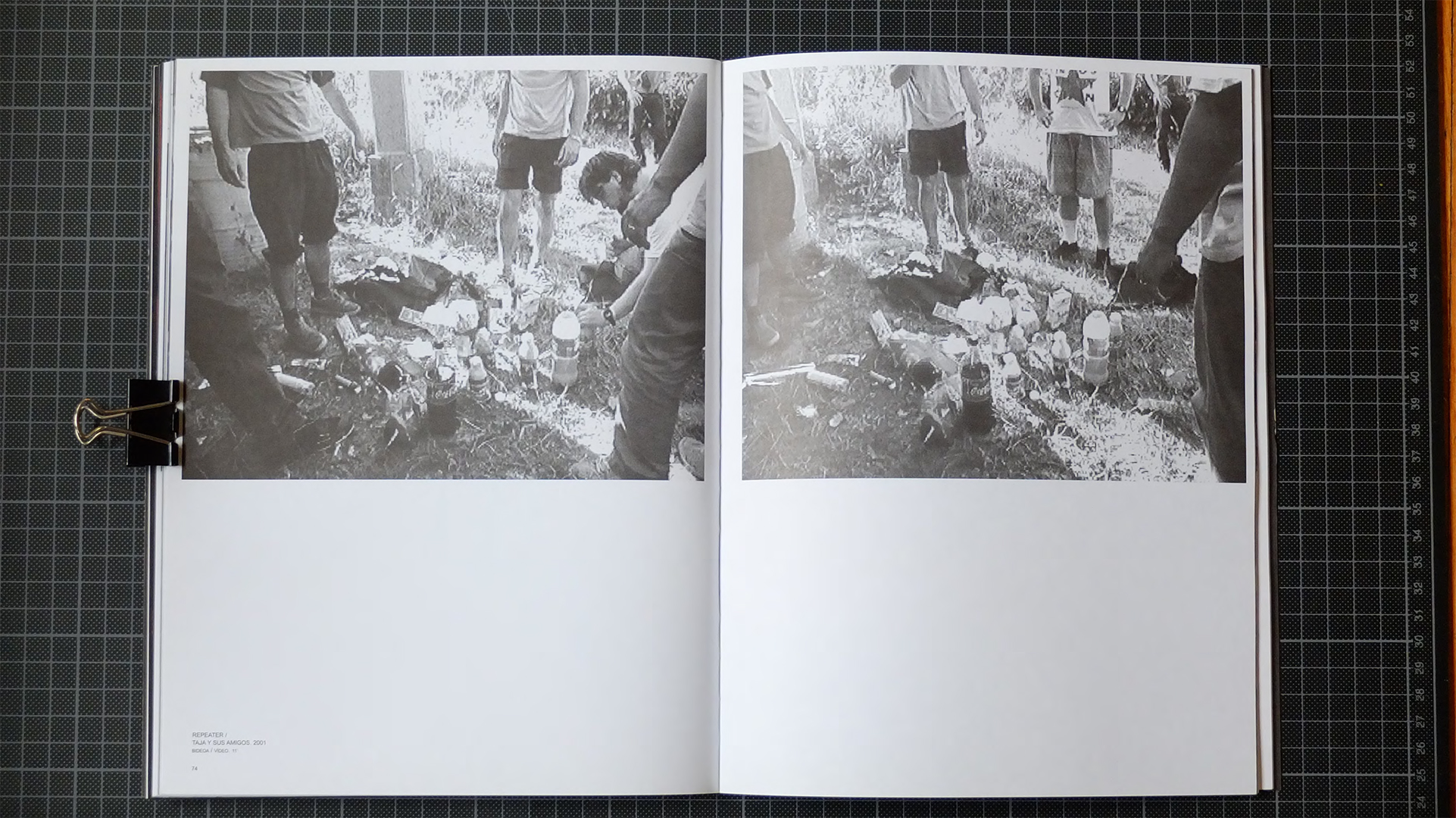

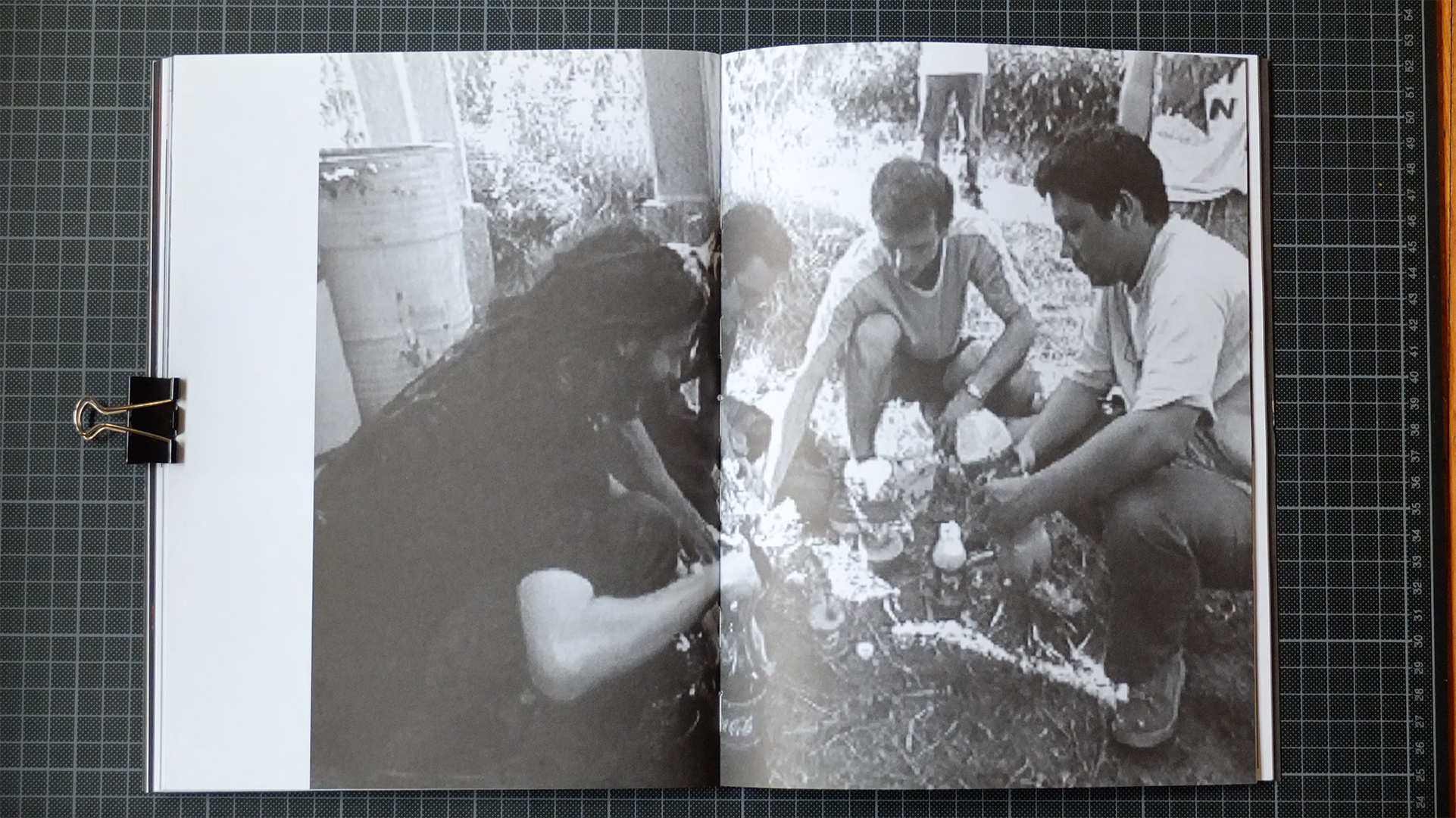

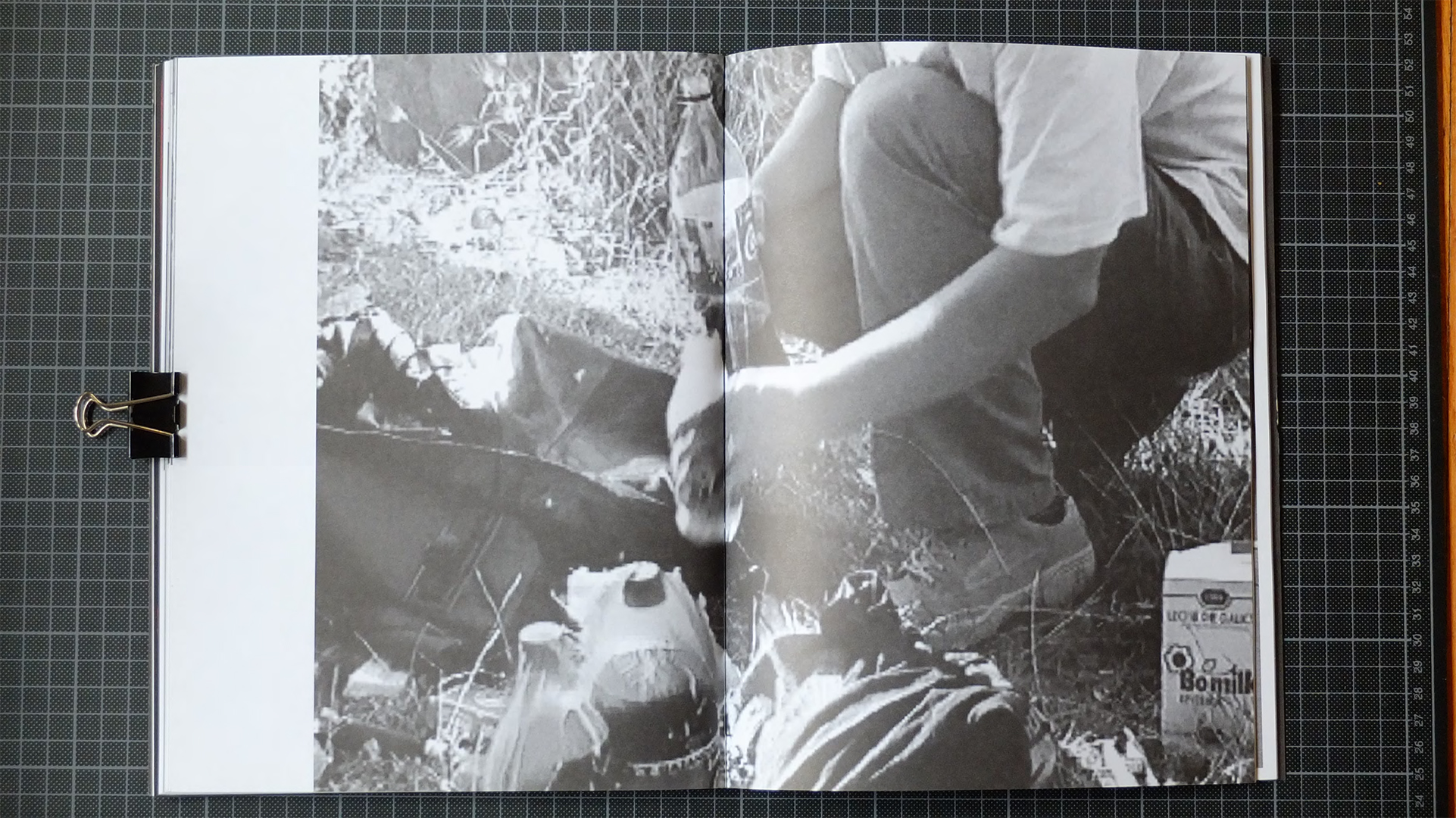

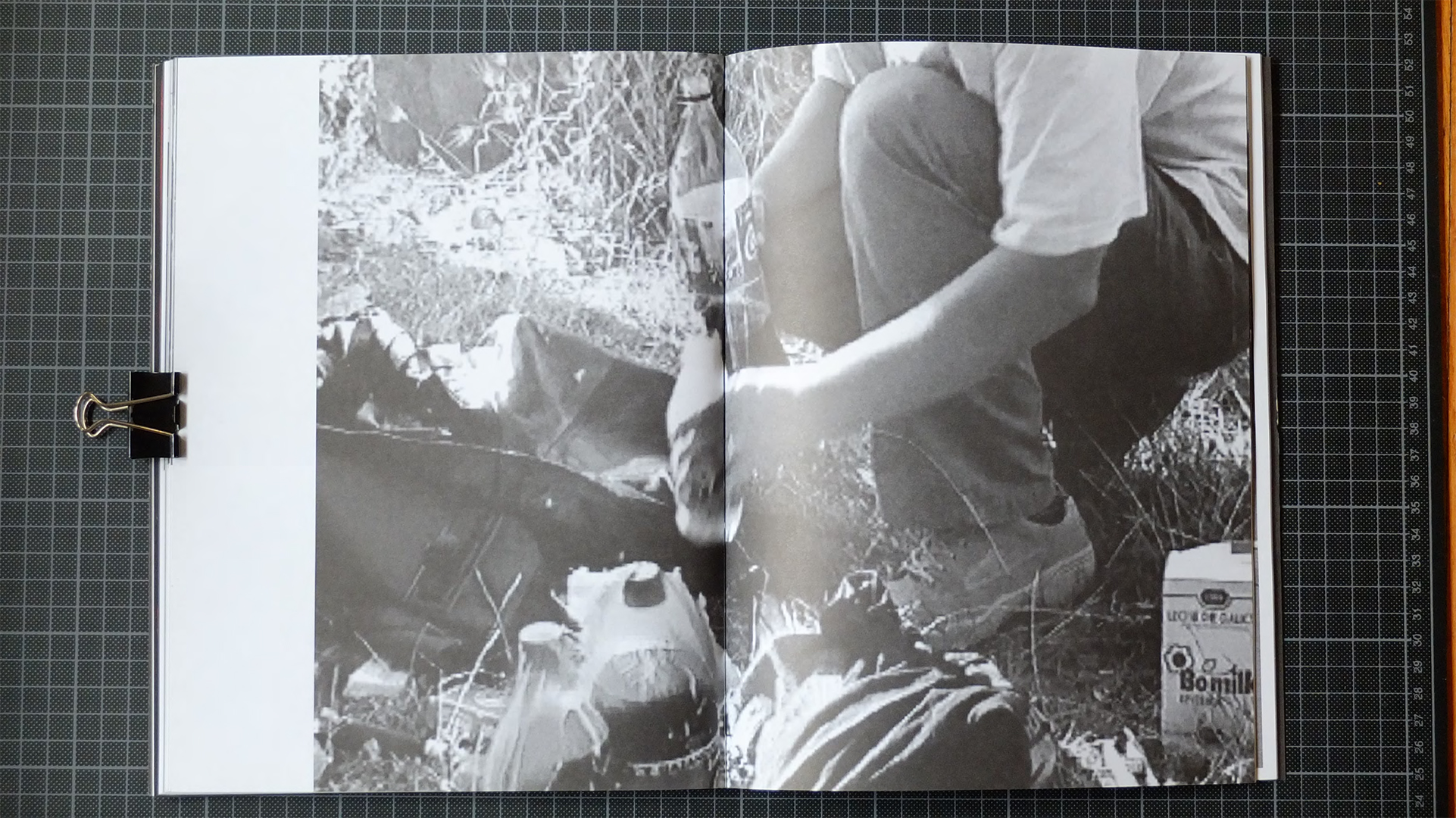

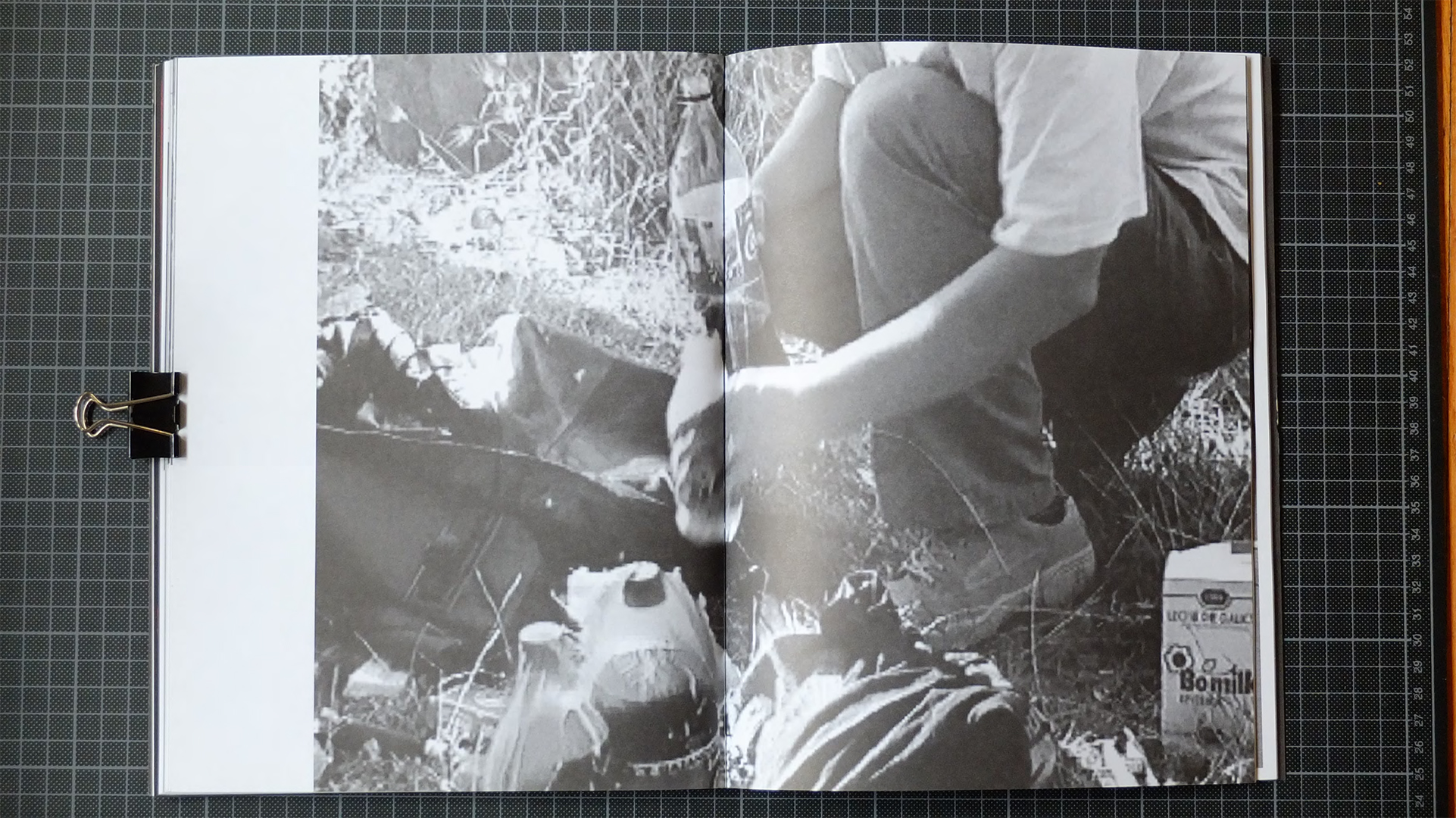

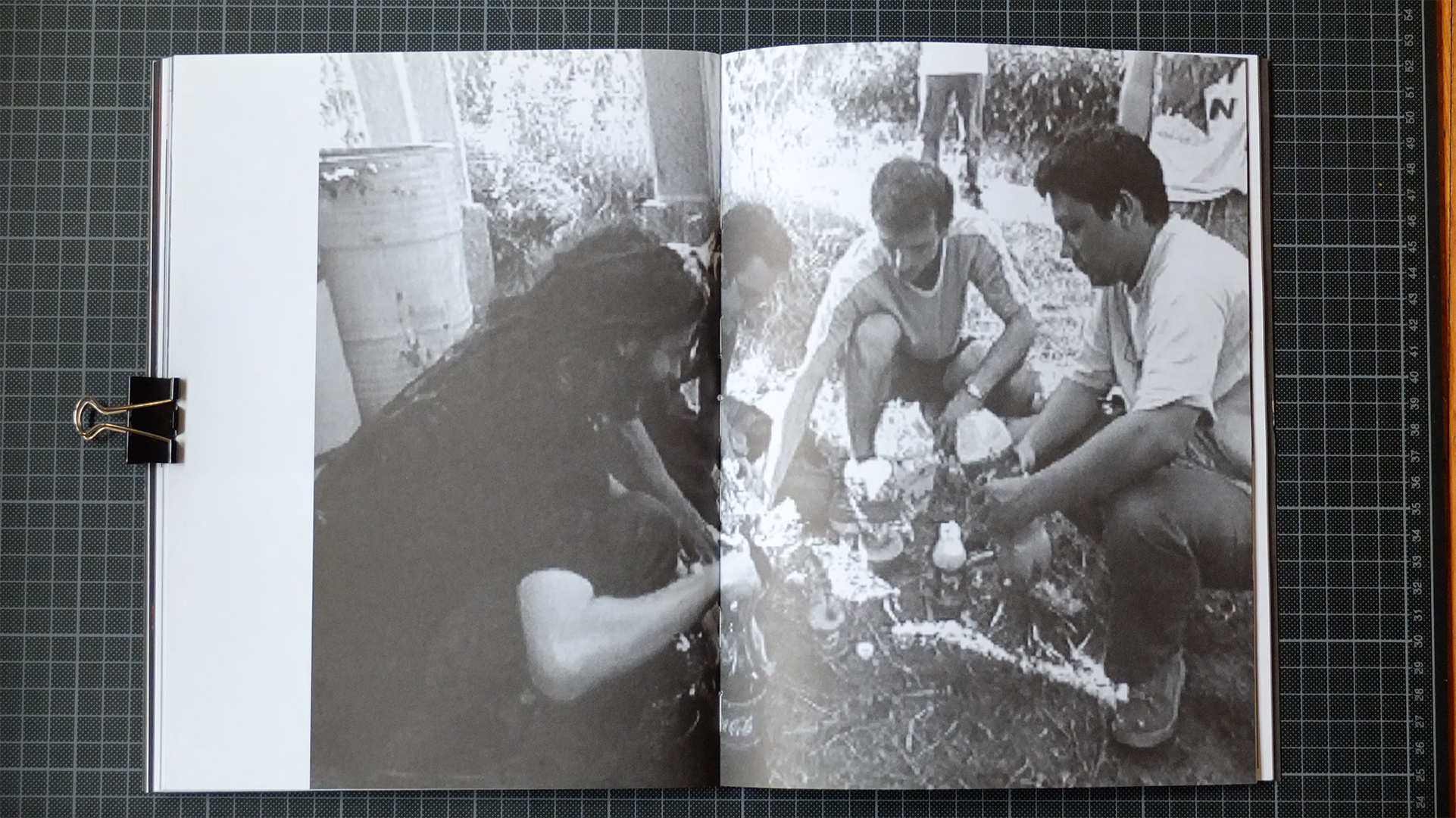

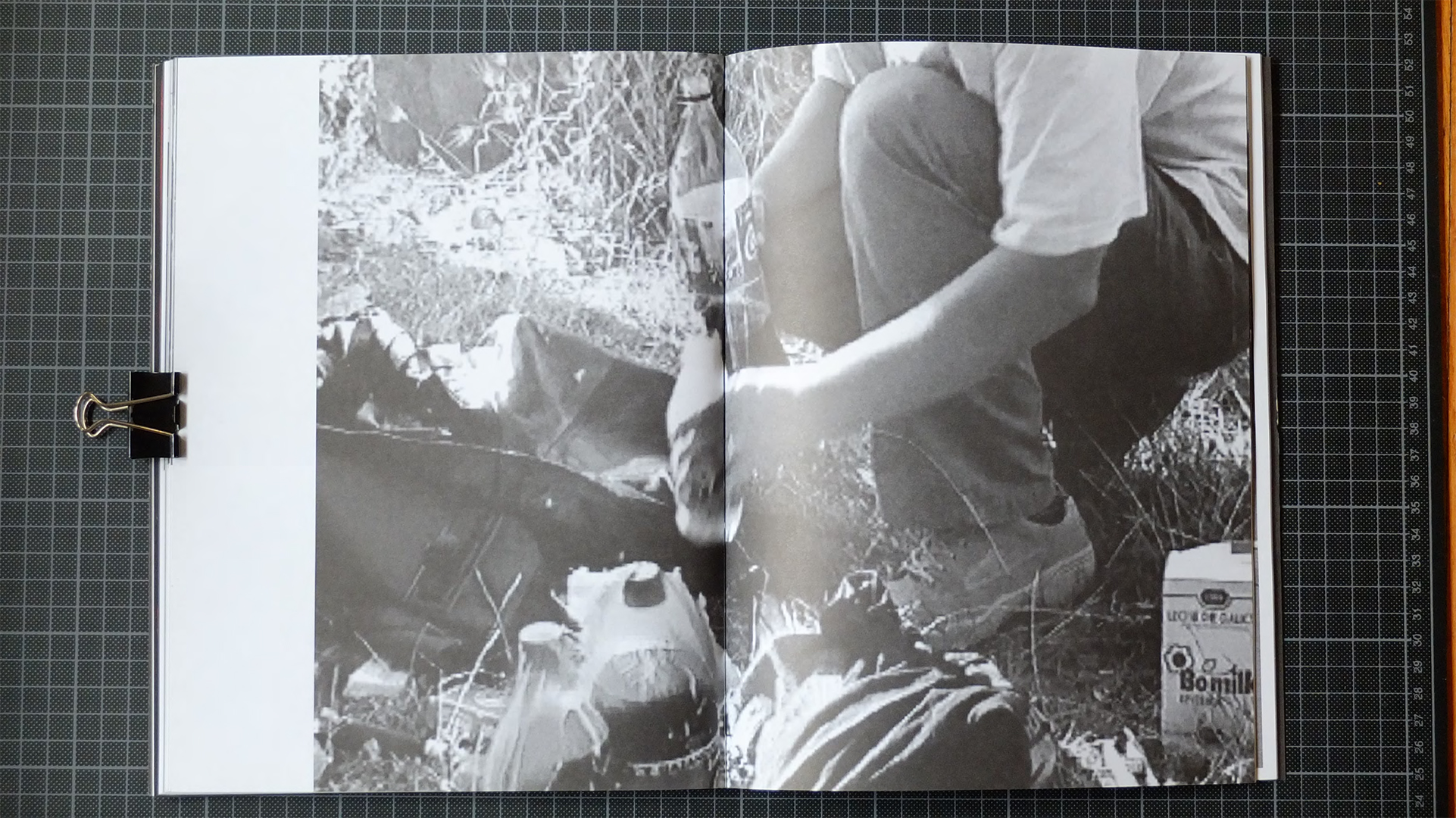

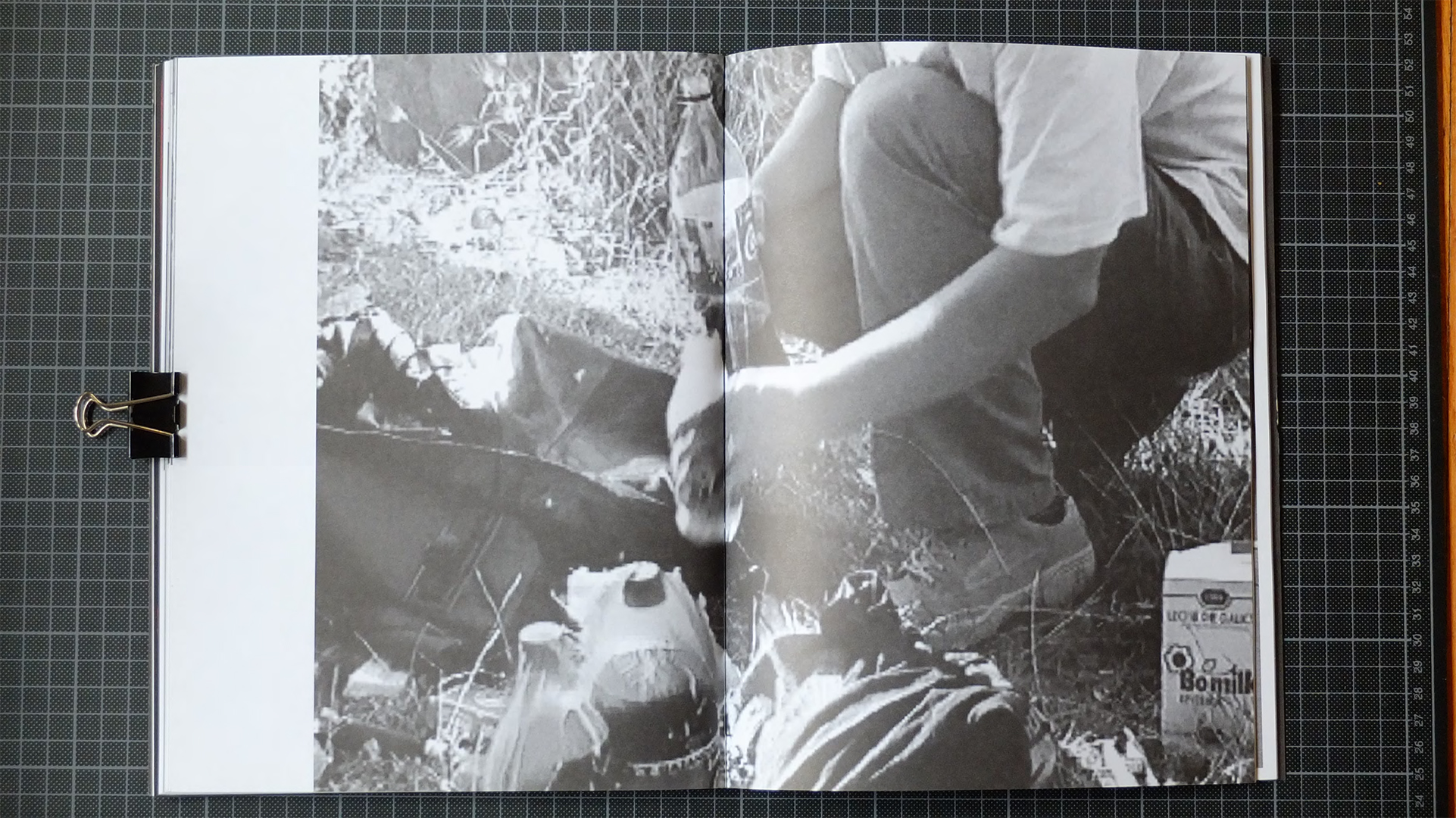

The scenes are built along the way, following a set of undefined rules. A group of young people step out of the frame and back into it as indicated. Together they develop a confusing composition, an ambiguous still life made of plastic, drinks, aluminium foil, duct tape and plasticine. The arrangement invites us to see it as a blurry form between paint and sculpture, onto which we can project a certain voyeuristic pleasure. Taja y sus amigos unfolds as a still life on a vacant lot by the train tracks and the road. In the beginning, the logic of arranging the elements in close up, typical of the aforementioned pictorial medium, is denied to some extent, as the resulting image is captured from a cautious distance, generating a feeling of alienation. As the video continues, the camera zooms in and a new arrangement of the frame offers a more detailed image. The light bathing the objects also reinforces the idea of pictorial composition. However, the camera’s distance remains contained at all times, despite progressively drawing closer, which prevents us from accepting the conformity of its nature. This might be caused by the composition refusing to be neither painting nor sculpture, merchandise nor footage/weapon. It merely offers itself as an ambiguous image facing the battleground of the TV medium.

A version with a rough transfer of the raw material was screened at the Festival Audiovisual de Vitoria-Gasteiz in 2000. Part of this screening involved broadcasting it at different times on TV. Later on, the final cut was exhibited on a monitor on a large, high stand in the installation Kolpez/Kolpe at the 2002 Taipei Biennial.

Related bibliography

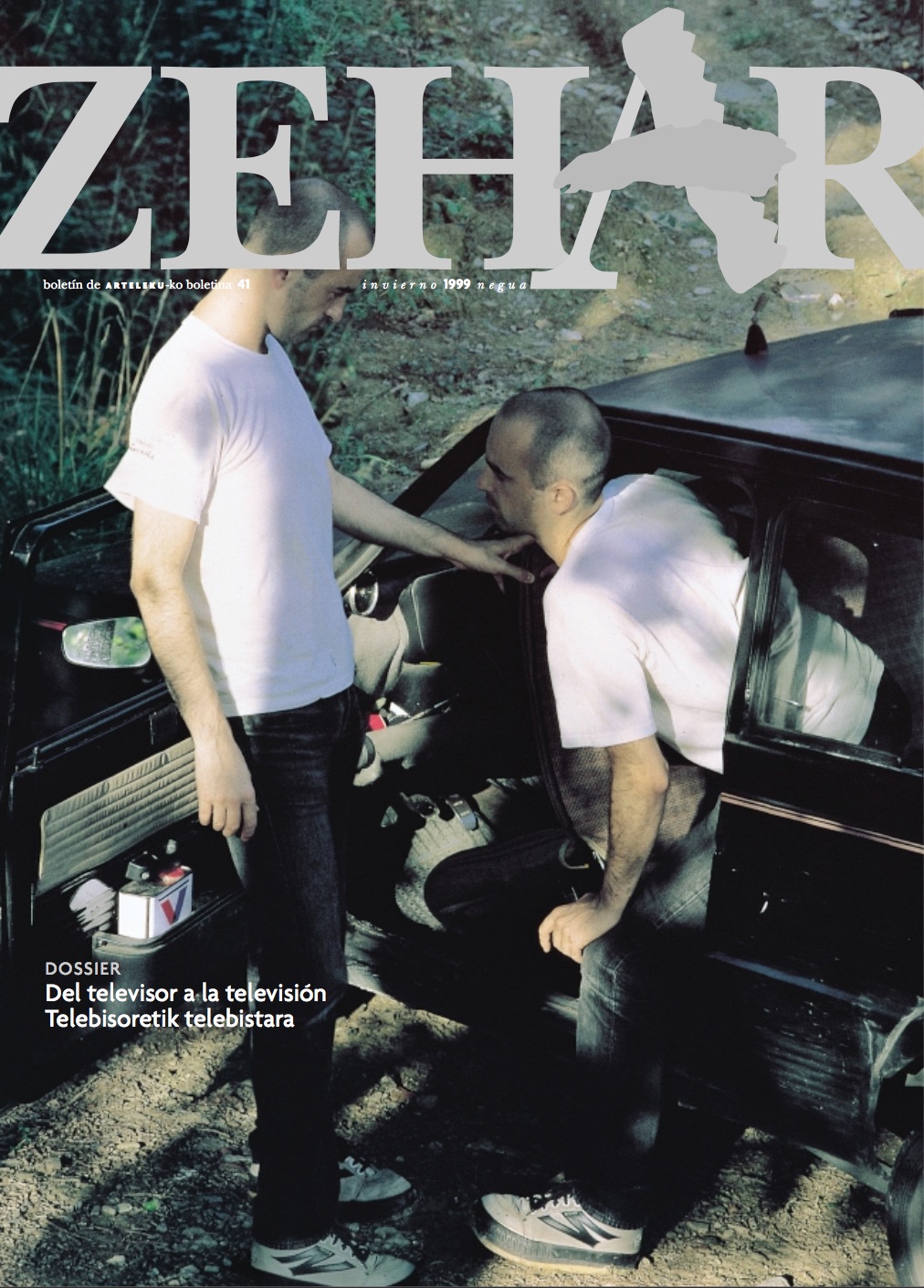

Zehar : Boletín de Arteleku. San Sebastian : Basque Regional Council, Department of Culture, no. 41 (Winter 1999), pp. 32-33.

Zehar magazine, published by Arteleku, San Sebastian , in which the “Gunea” section, coordinated by Asier Mendizabal, includes works by Aernout Mik and Iñaki Garmendia (two stills from Garmendia’s video Taja y sus amigos (1999) with extracts of dialogues) [pp. 32-33]. Download.

Peio Aguirre. “Basque report 2.0”, Lápiz, no. 178, Madrid, December 2001, p. 50-57.

Article by Peio Aguirre on the current situation of art in the Basque Country. Cites Garmendia’s work and illustrates his video Taja y sus amigos (1999). Originally published in Arts.zin : crítica online de las nuevas prácticas artísticas Madrid, vol. II, October 2000 – July 2001. Text in images courtesy of Peio Aguirre.

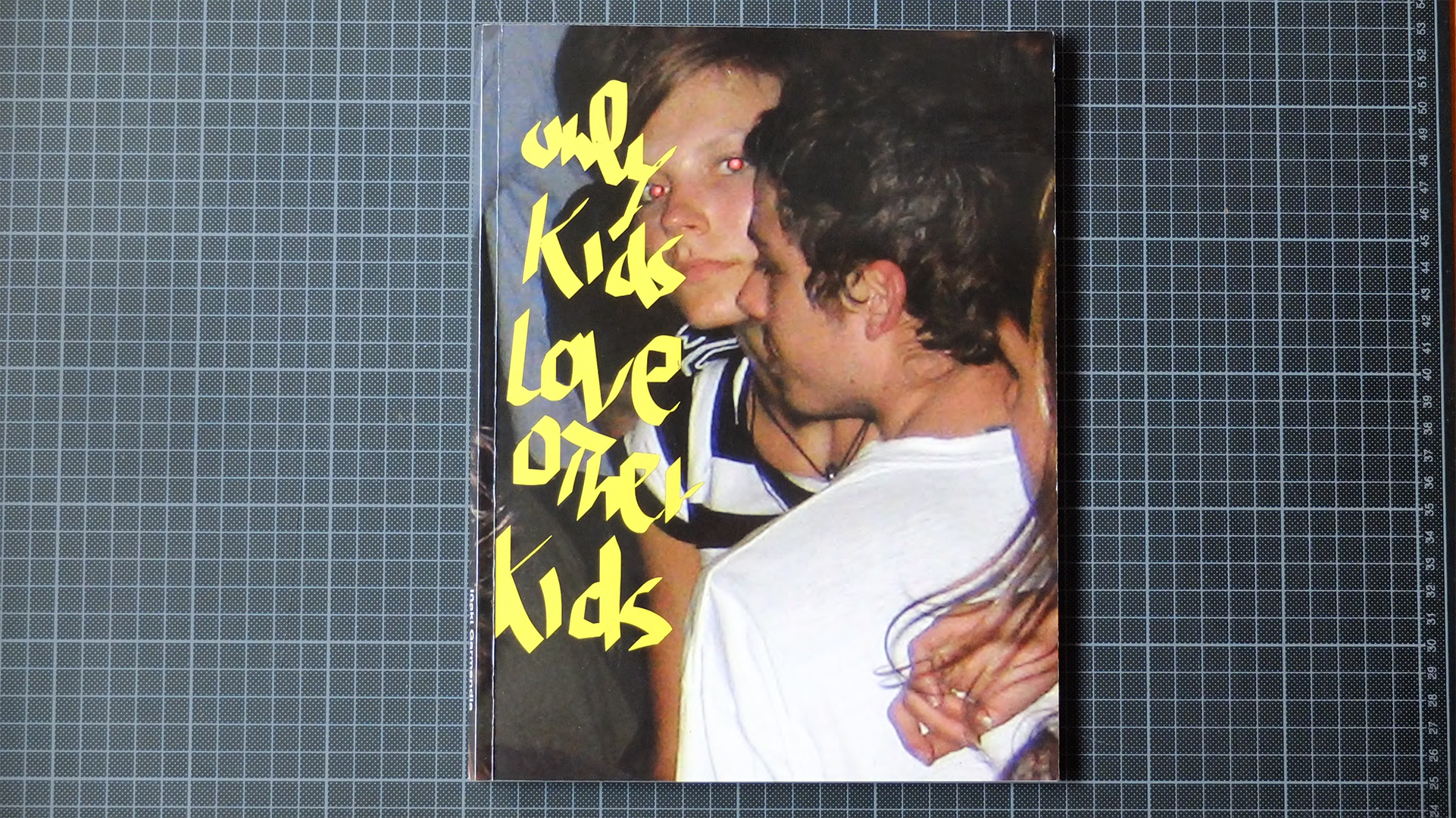

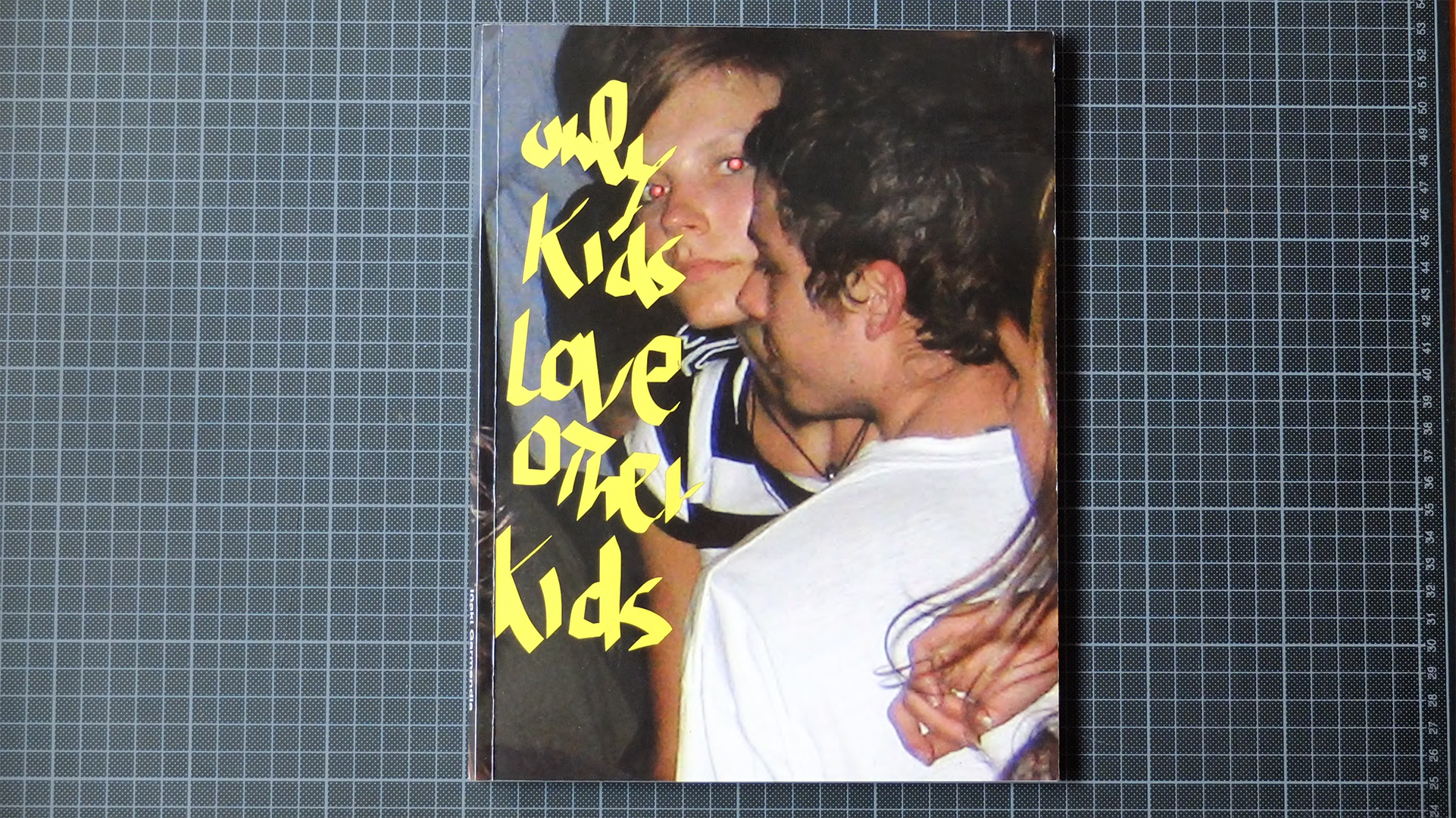

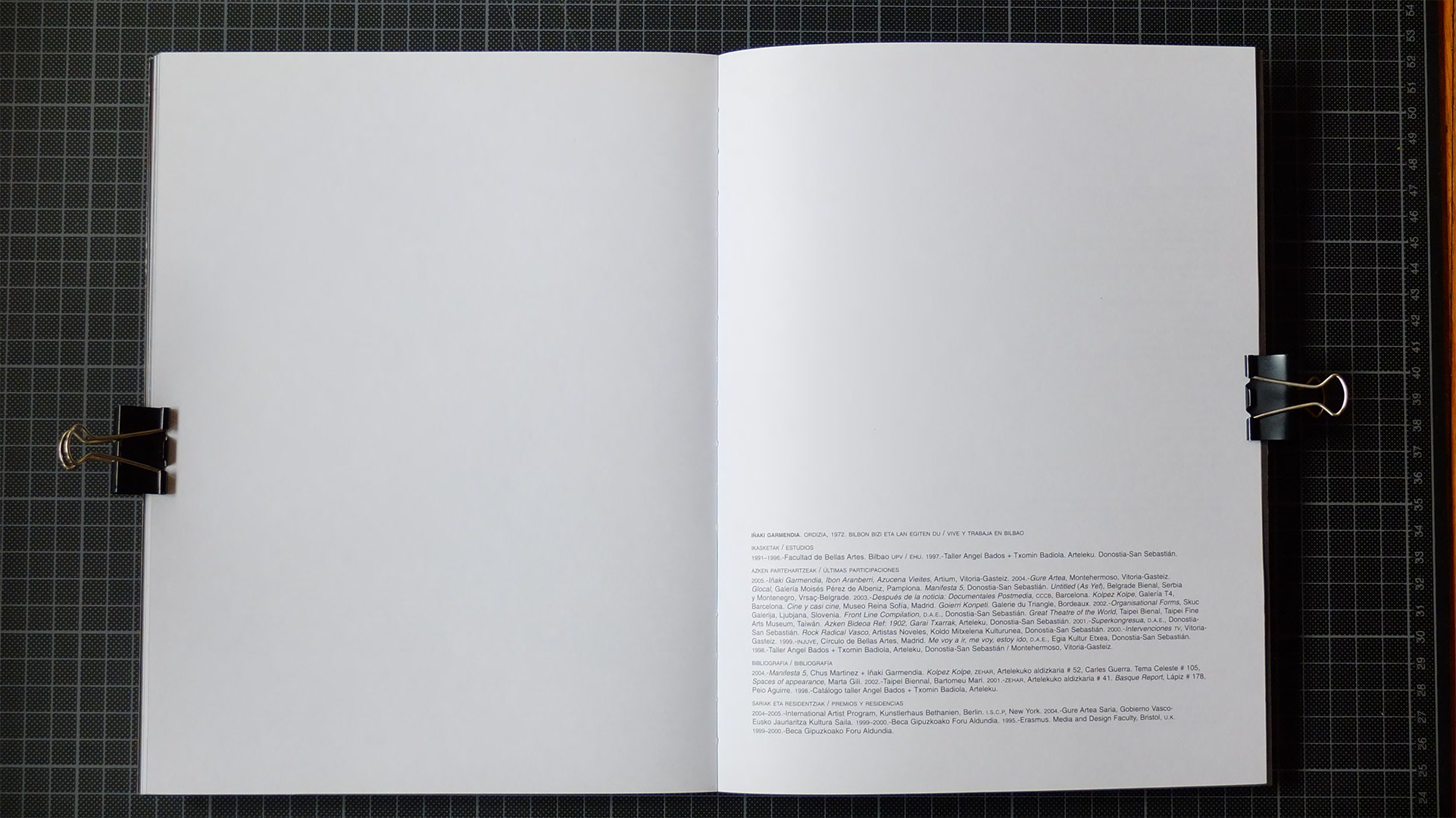

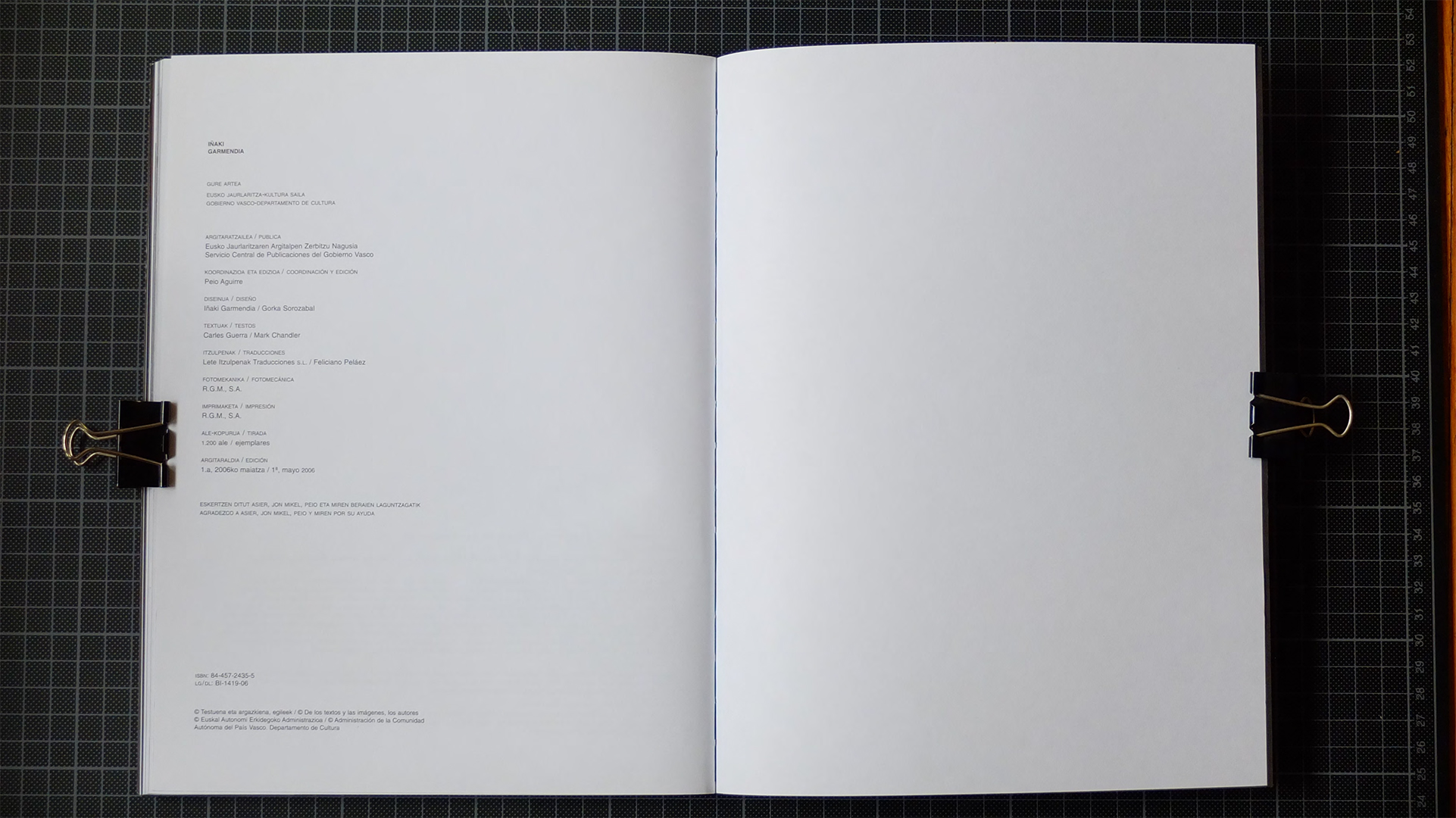

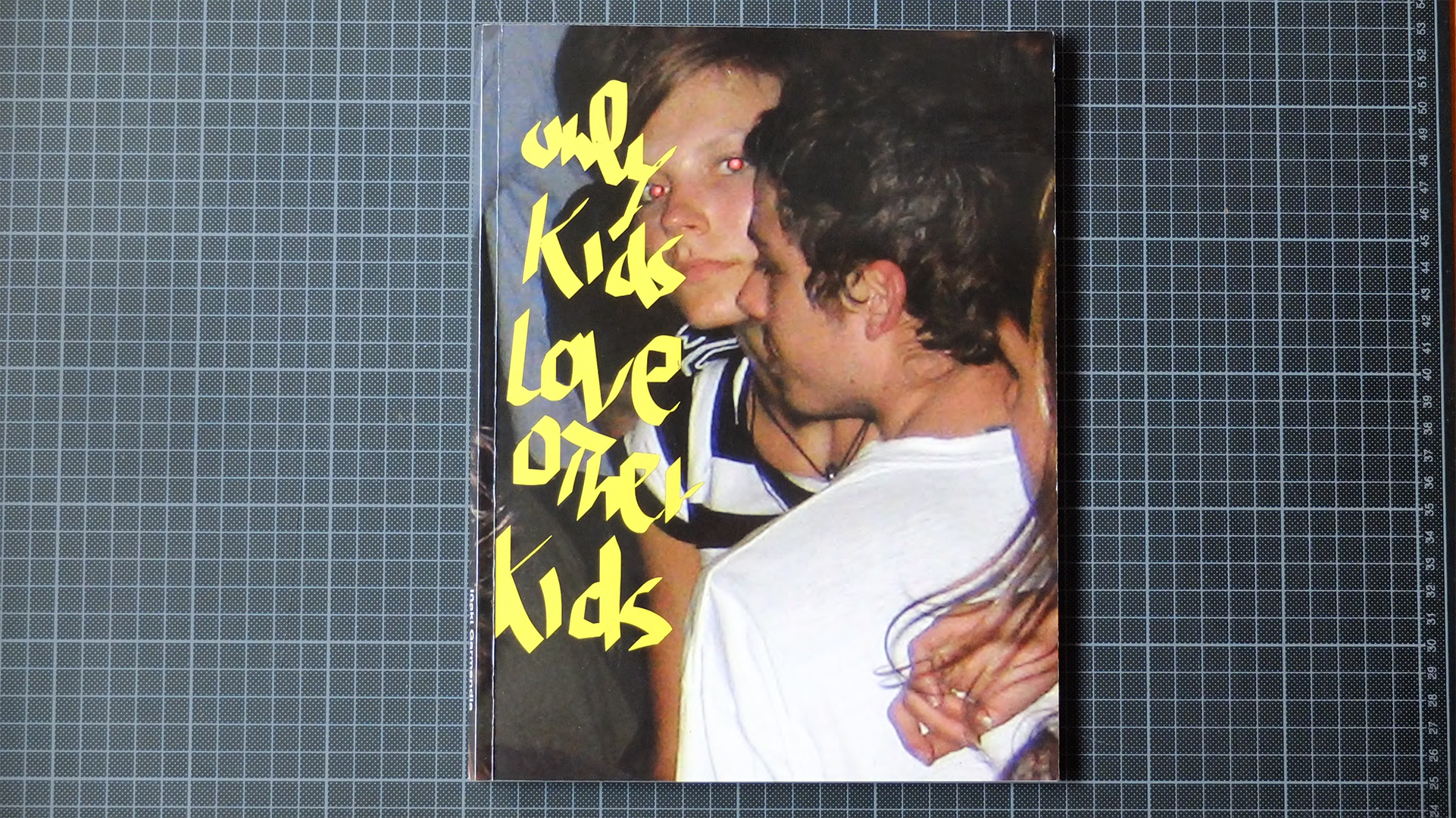

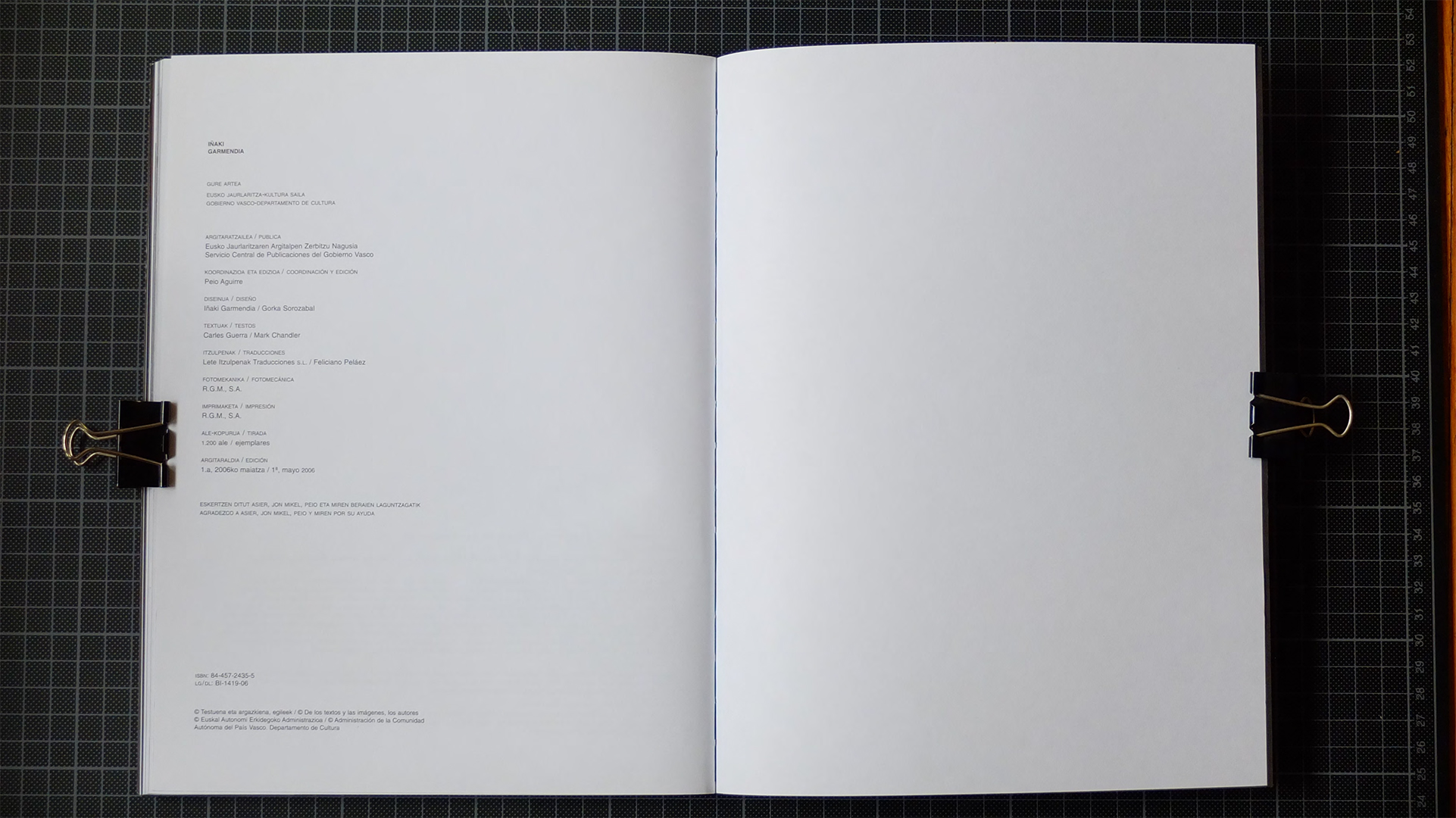

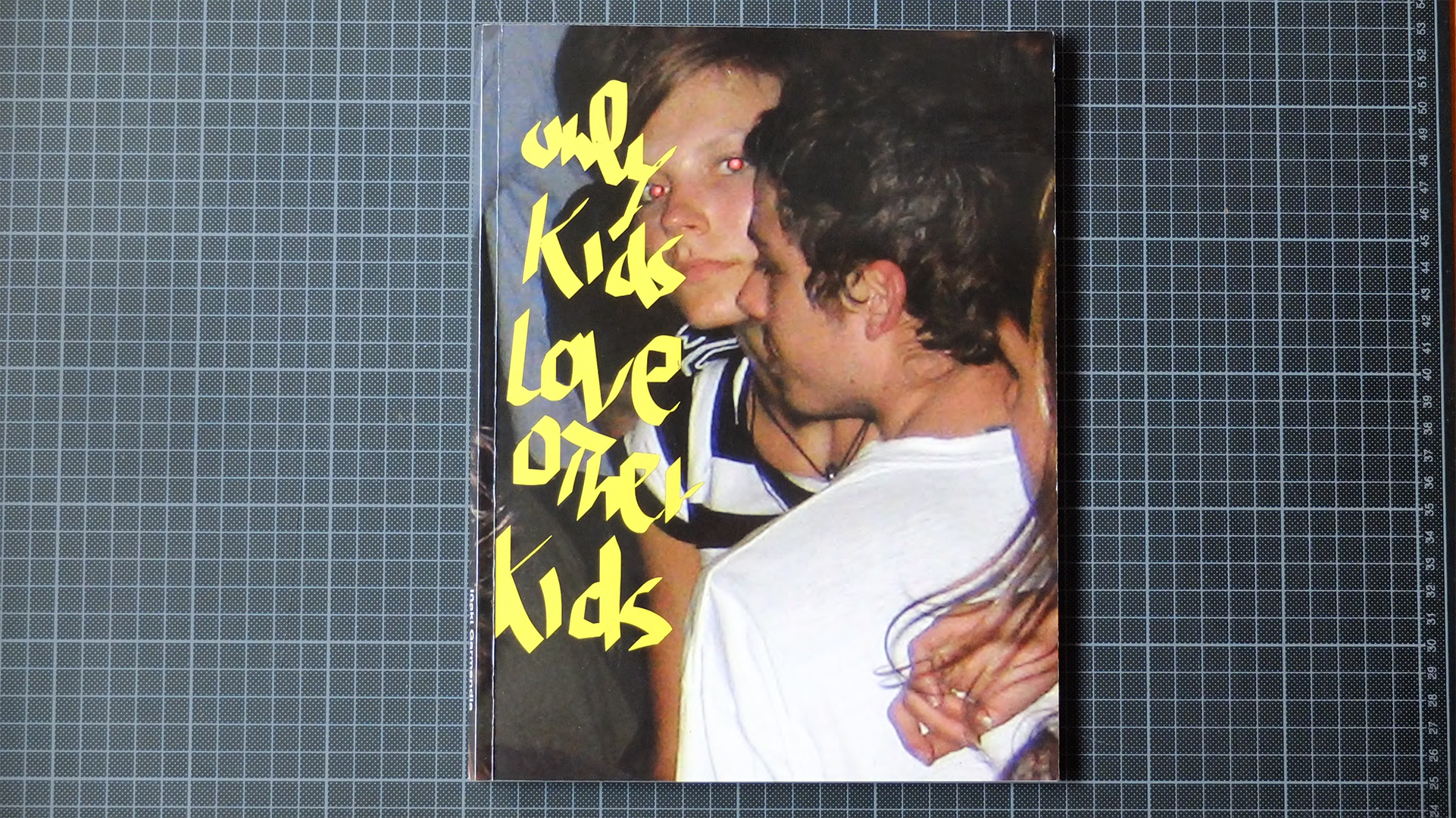

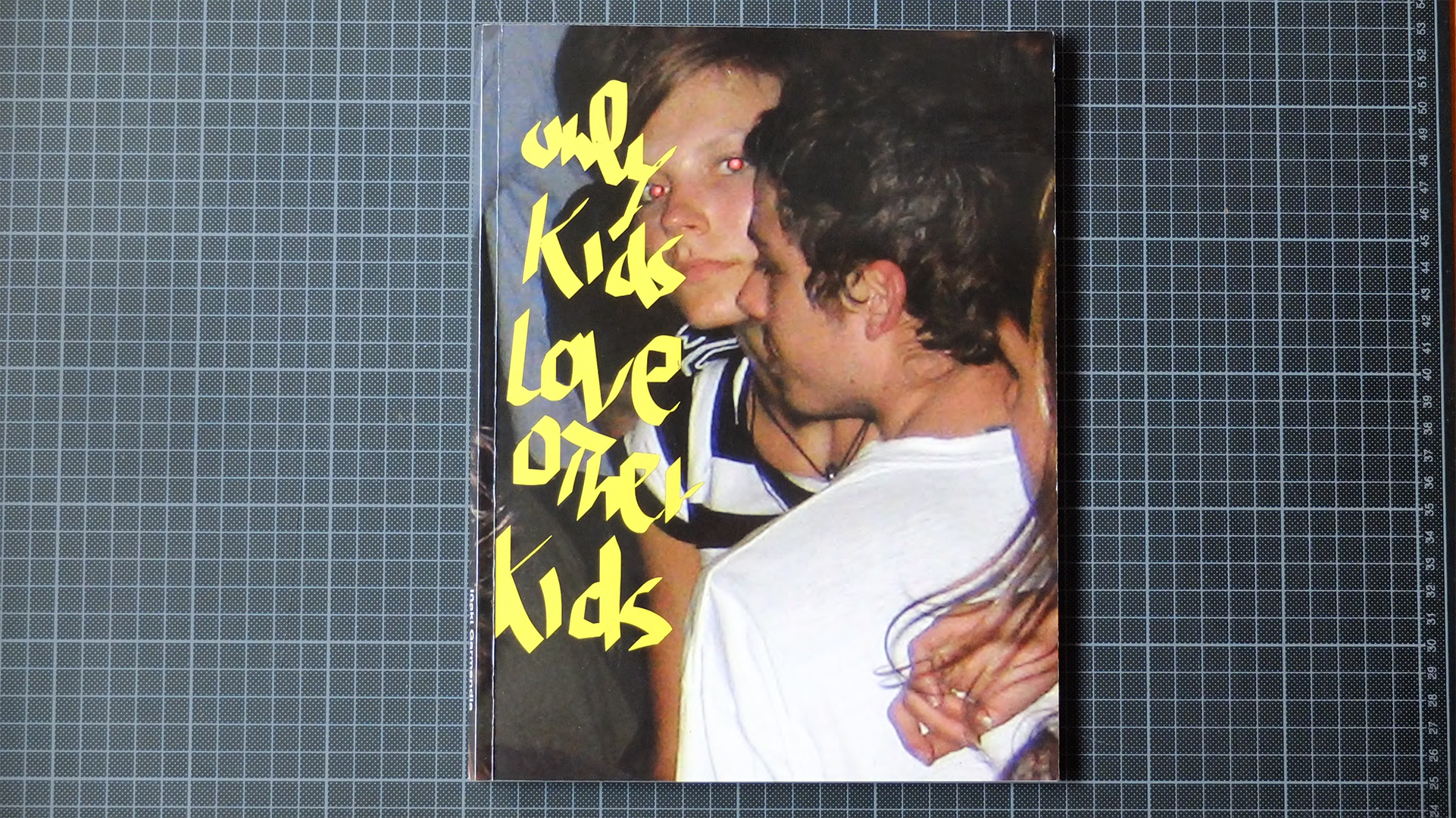

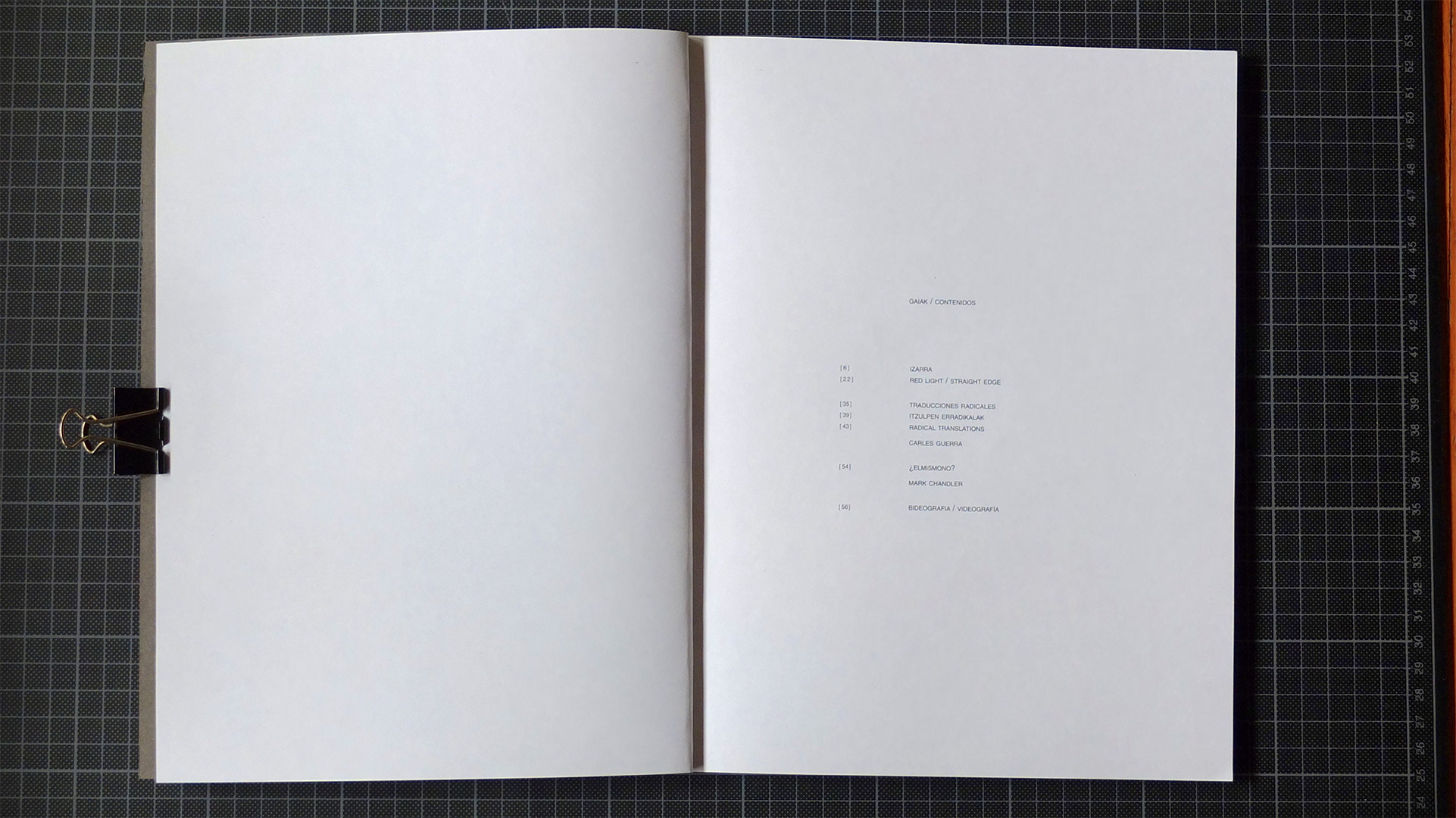

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

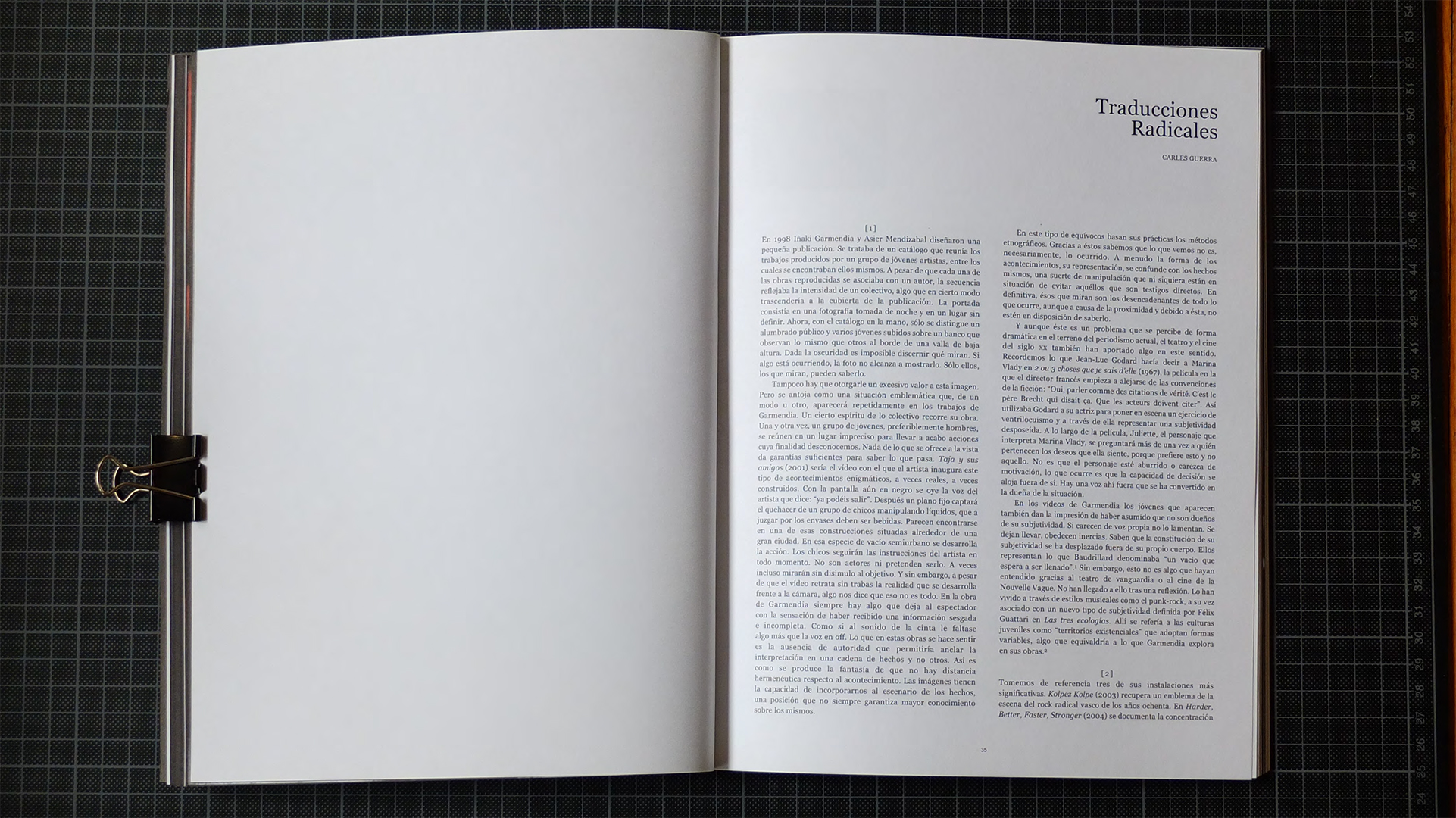

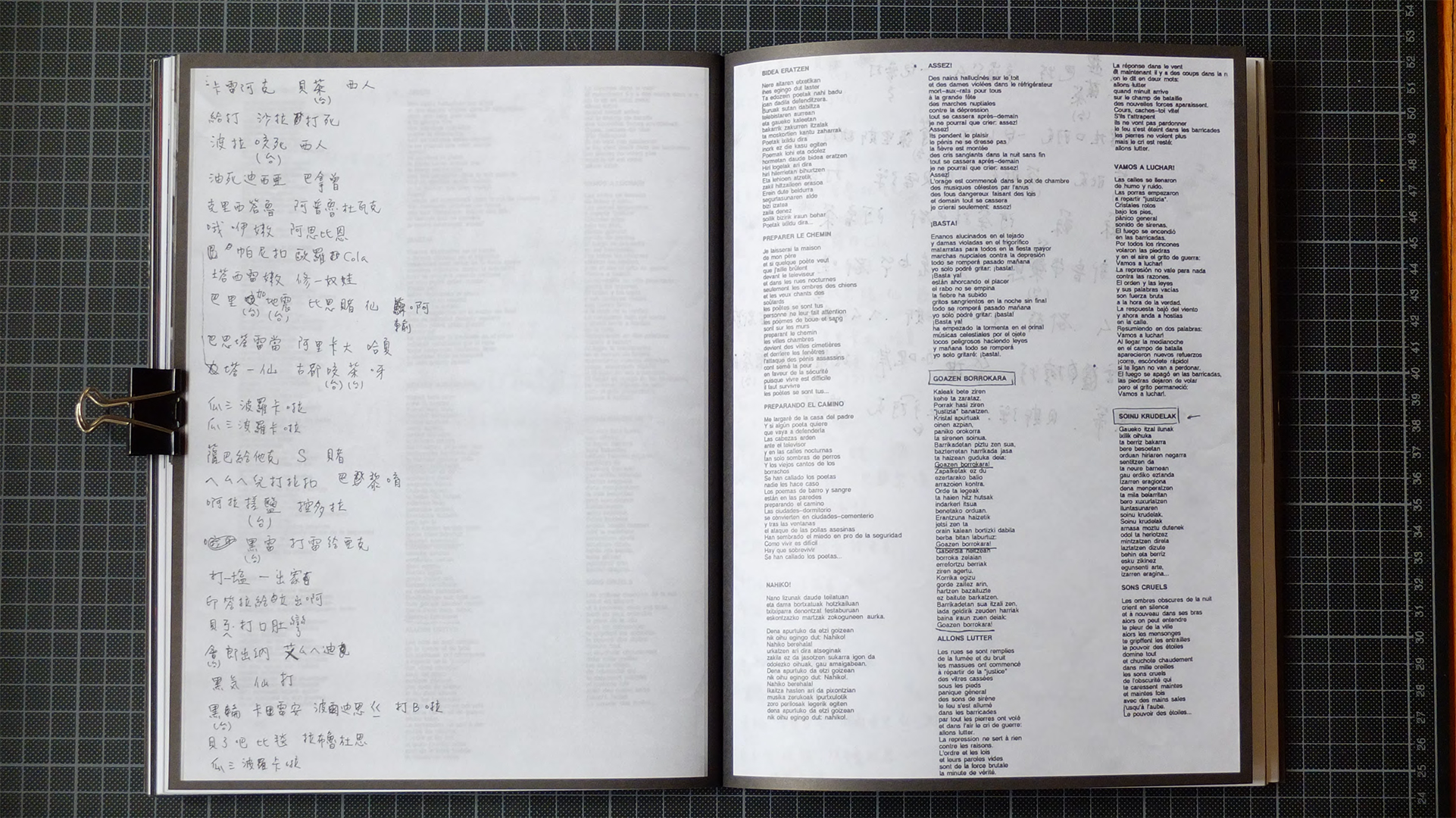

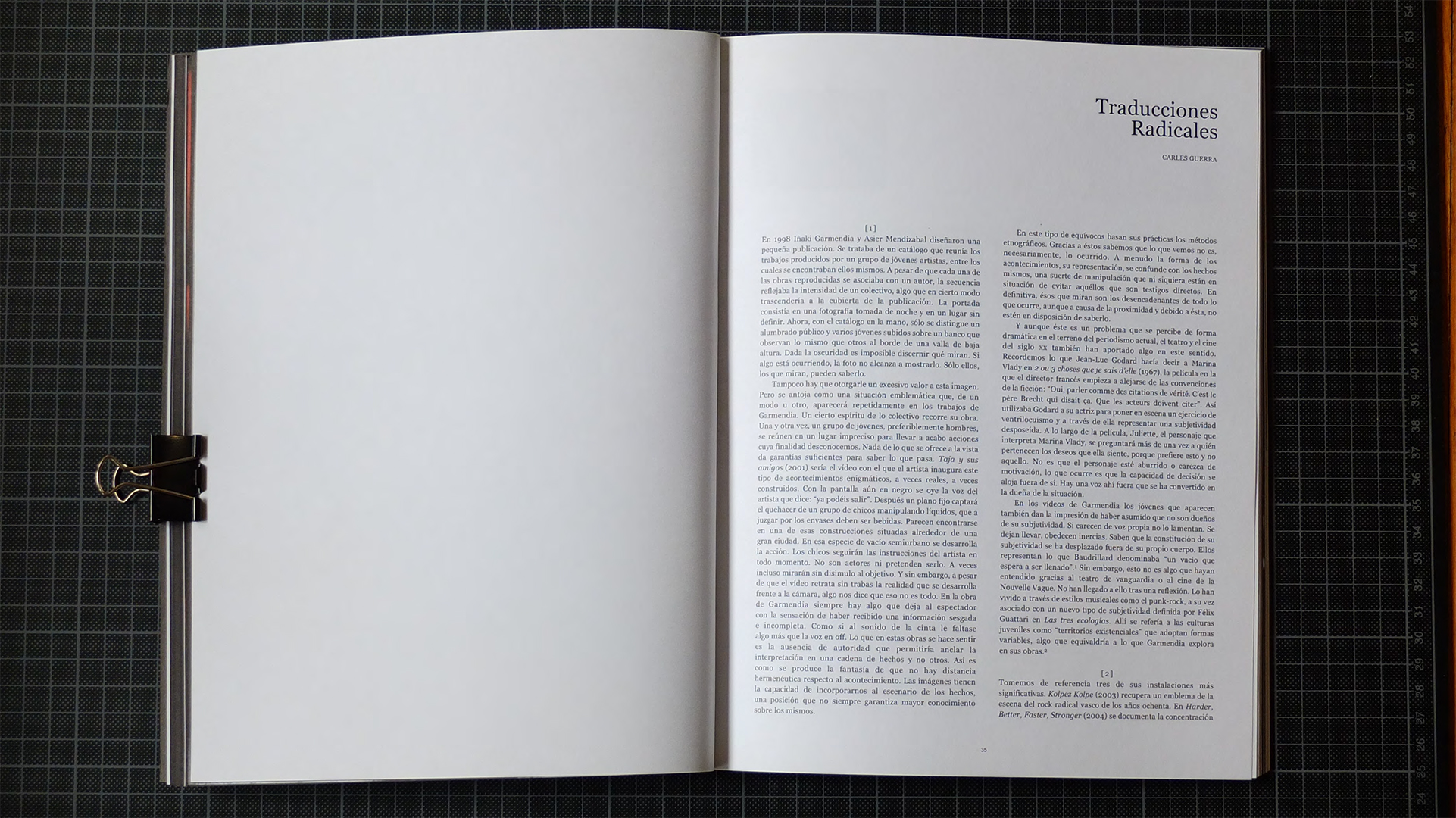

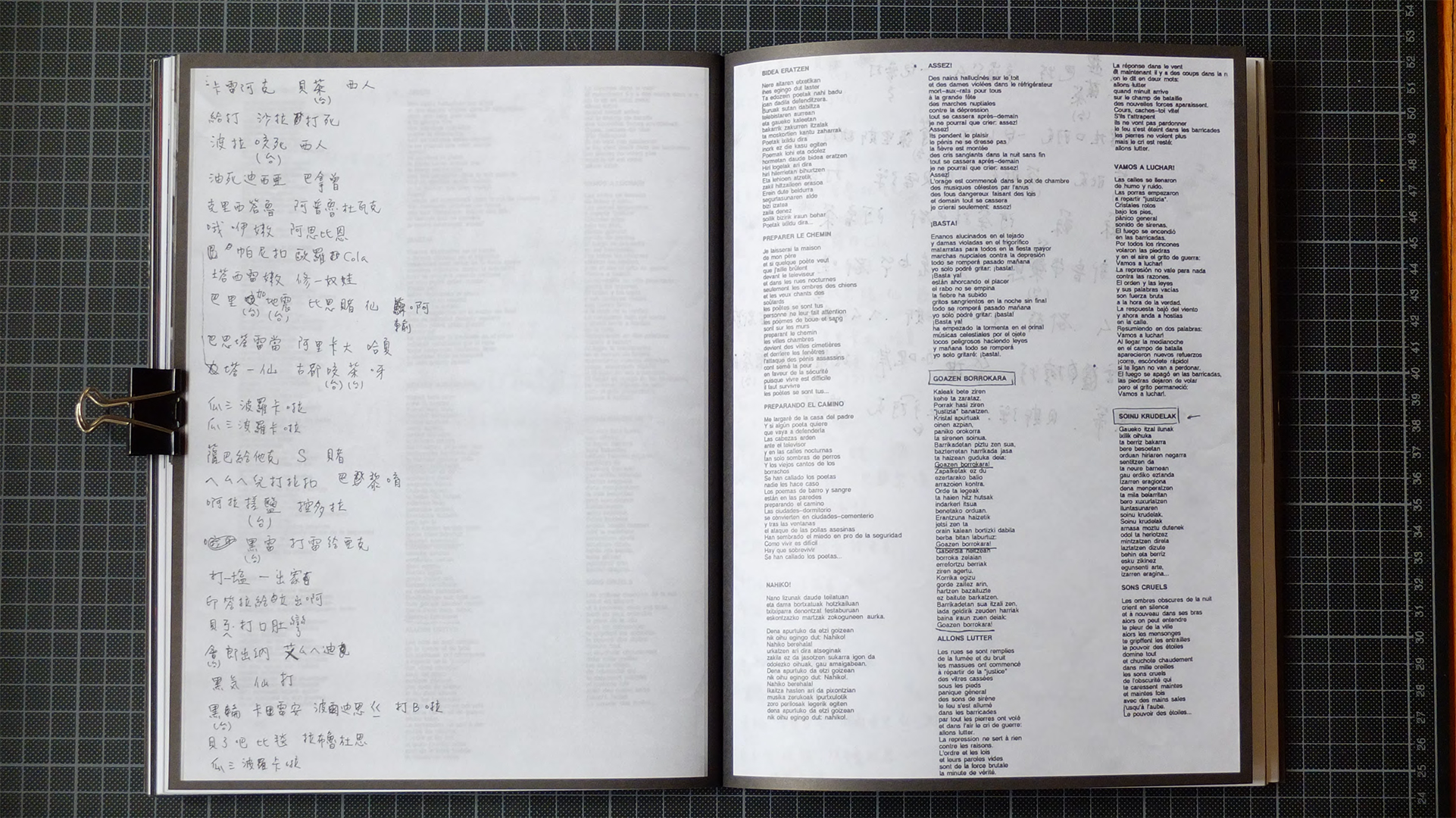

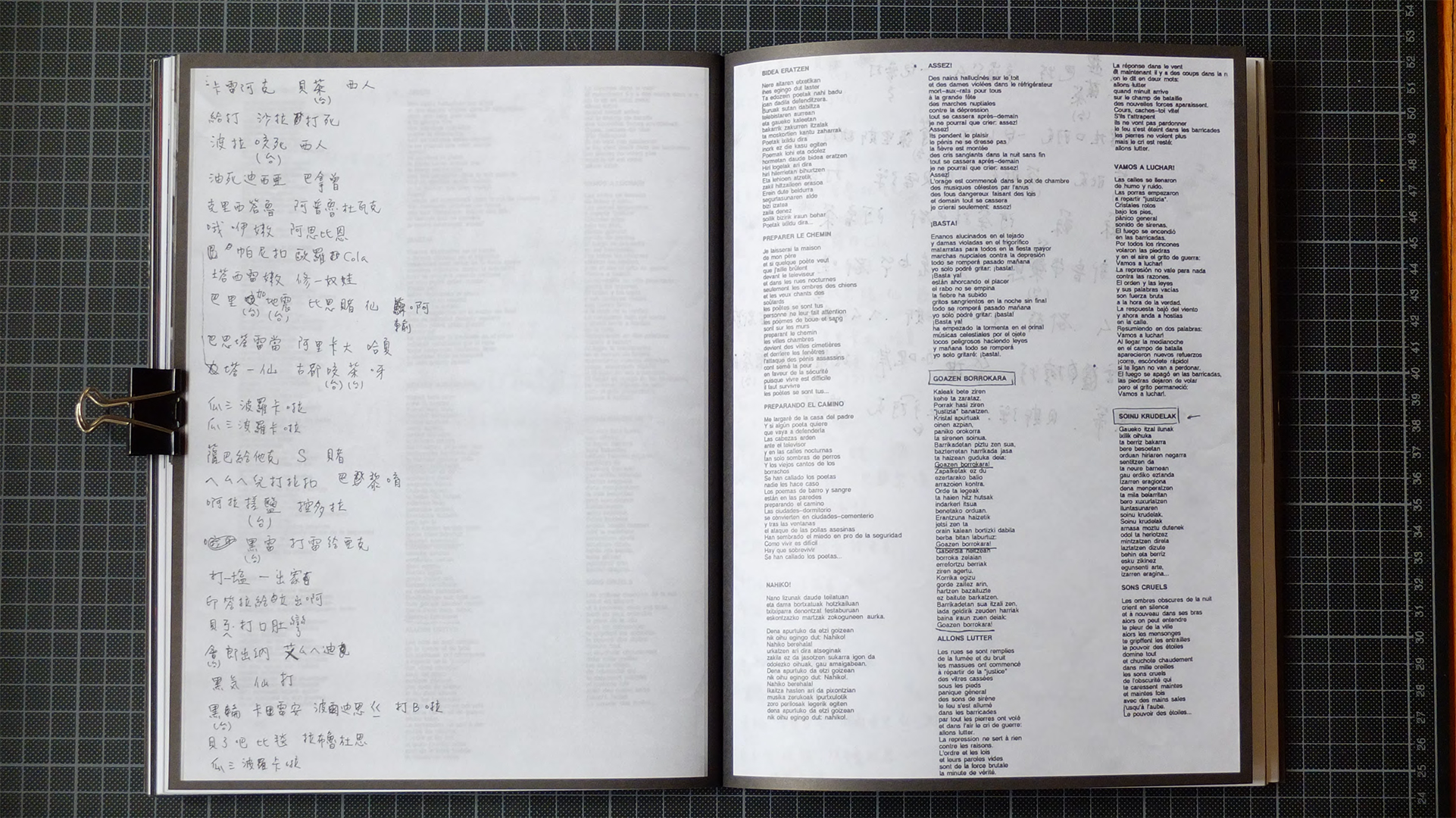

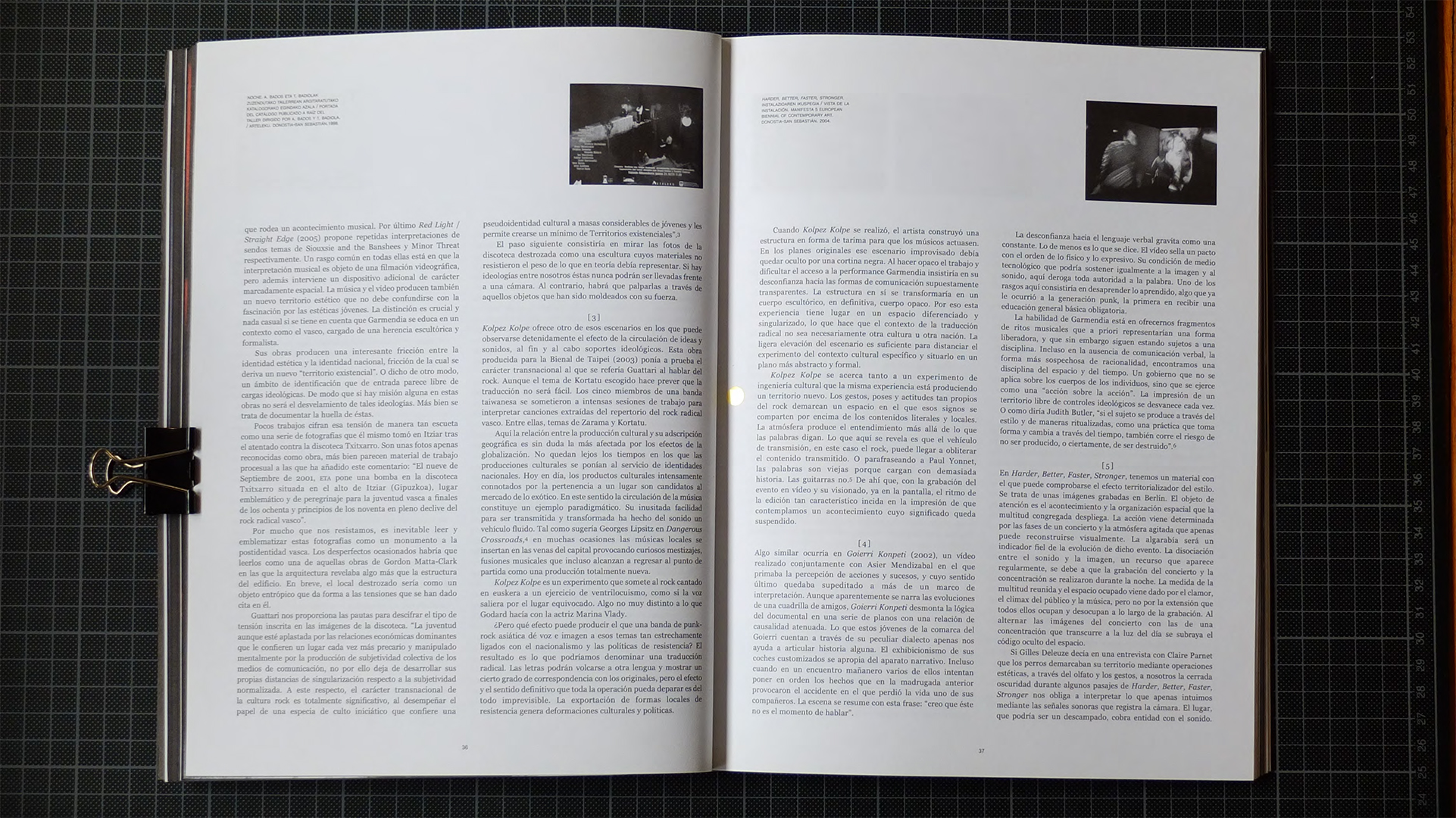

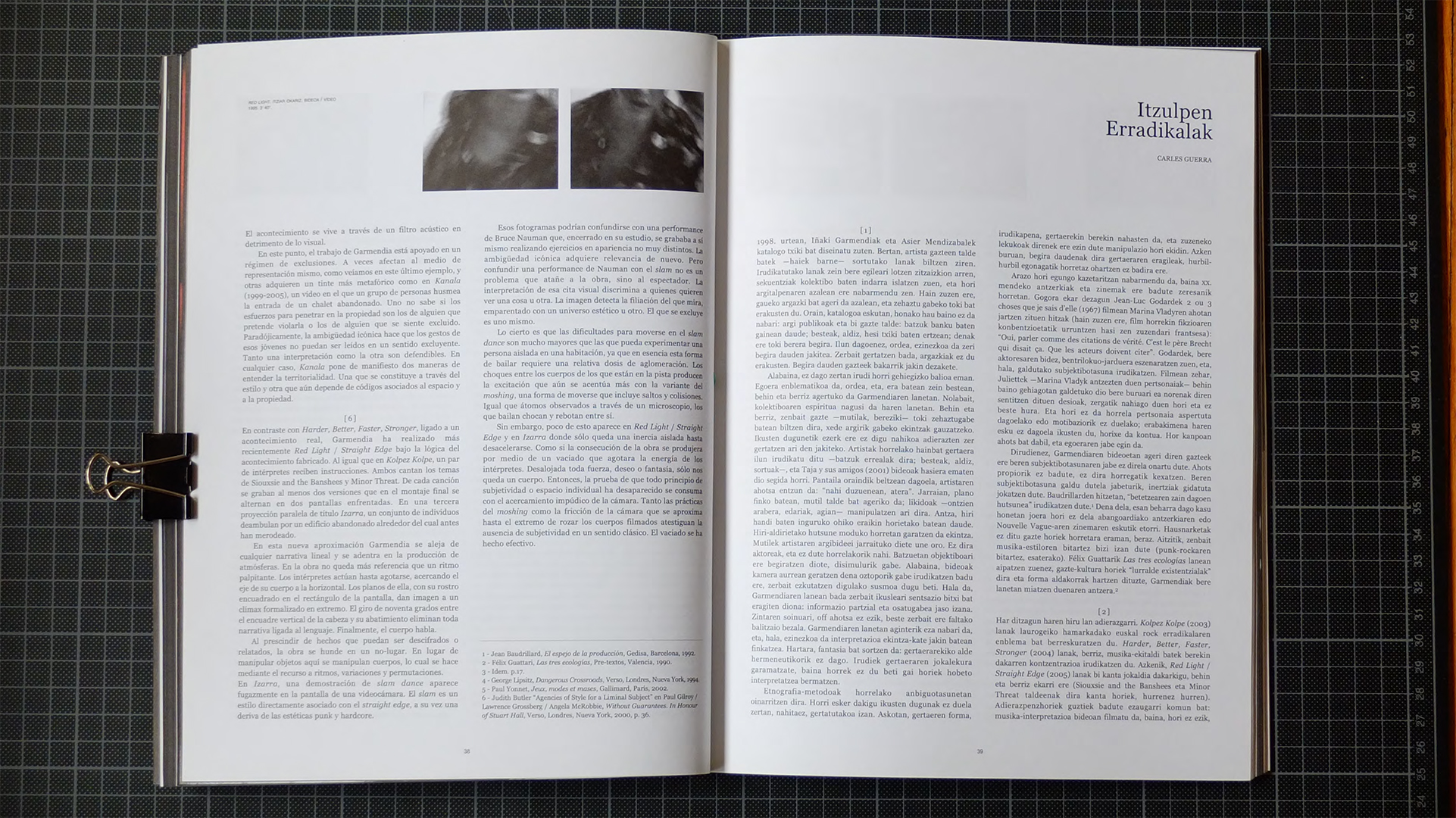

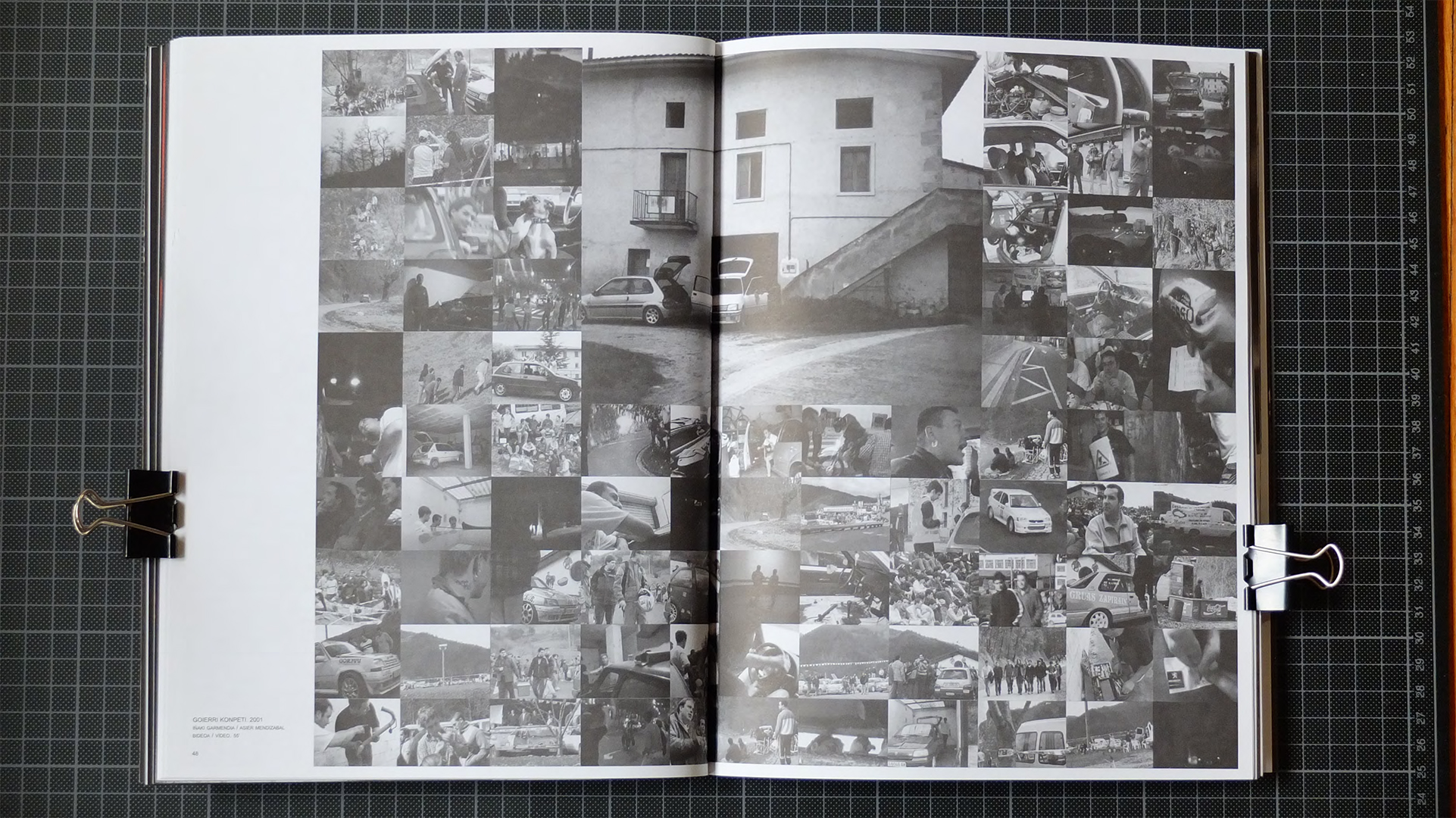

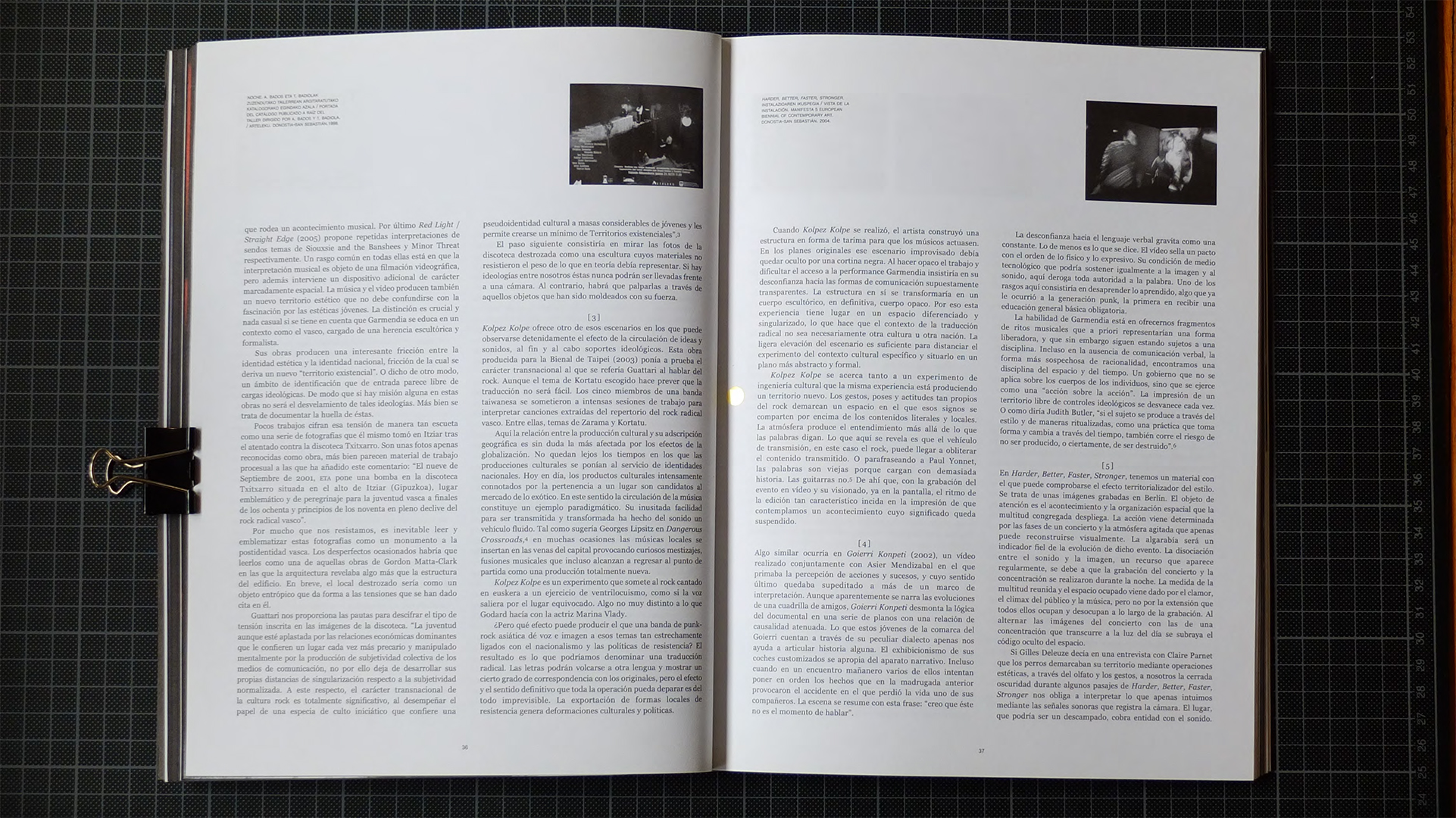

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

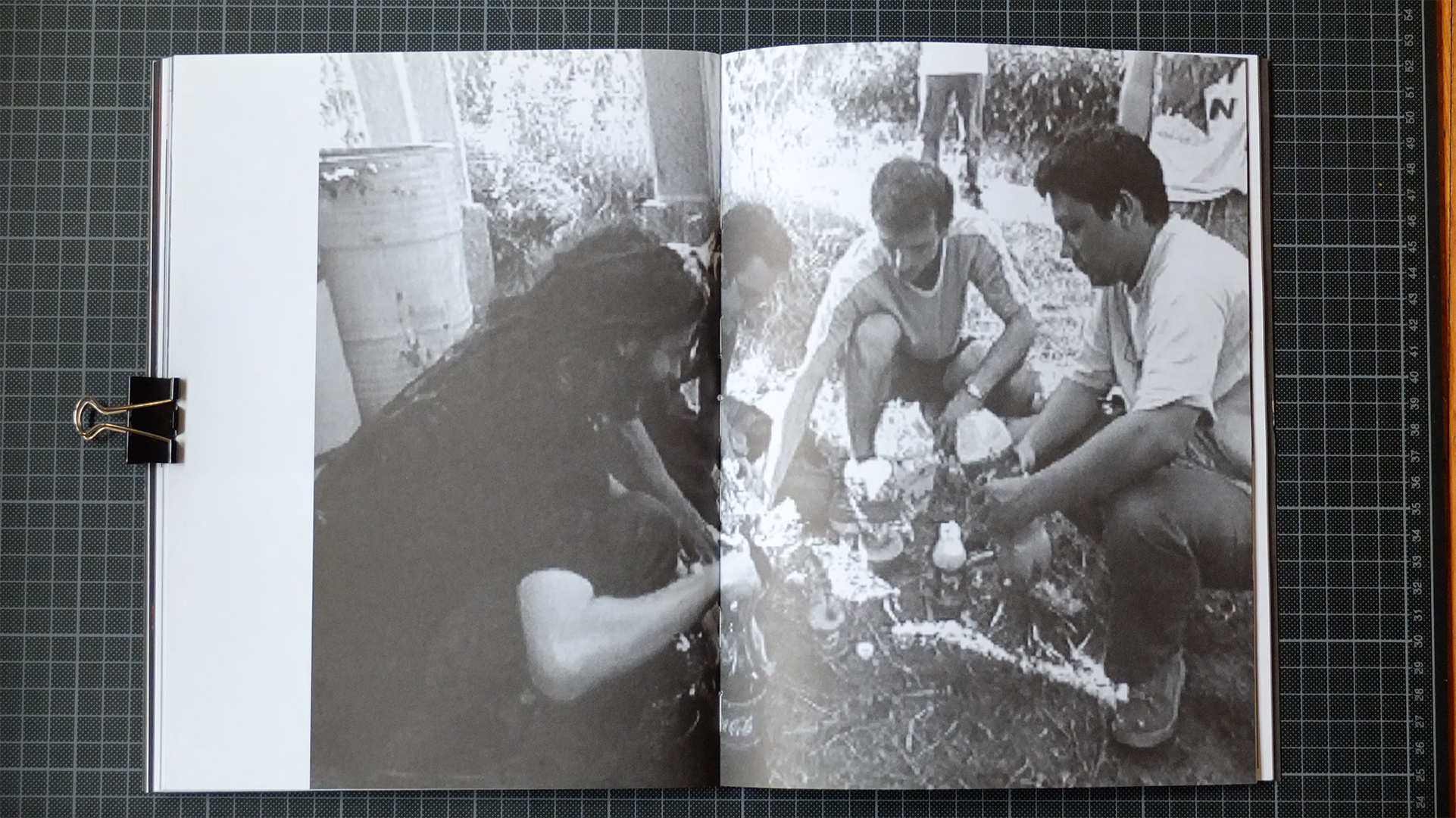

In collaboration with Asier Mendizabal

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

53’35’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

The work An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is Not An Artist by Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović —produced in 1992, only a couple of years after the fall of the Berlin wall— helps to situate the difficulty that carrying out a retrospective on the early 90s in the international art context implies. This was a transitional period, as described by the —also Croatian— curator collective WHW as “the narrow-minded local interests clash with the implacable and ever-present logic of capital and globalisation”. Stilinović’s precept, sewn on a pink piece of fabric in the form of a banner, questions the hegemony of English in the capitalist Western art world, hungry for great narratives and reluctant to devote its efforts to listening to specific types of storytelling from the periphery. In the early 2000s, the transition initiated during the 90s brought forth a new process of normalisation in contexts such as Croatia and other ex-Yugoslavian territories. This transformation comes at the same time —as pointed out also by WHW— as “the promise to progress towards the normalcy of late-capitalist Western societies, considered as welfare states in which human rights would be fully respected”.

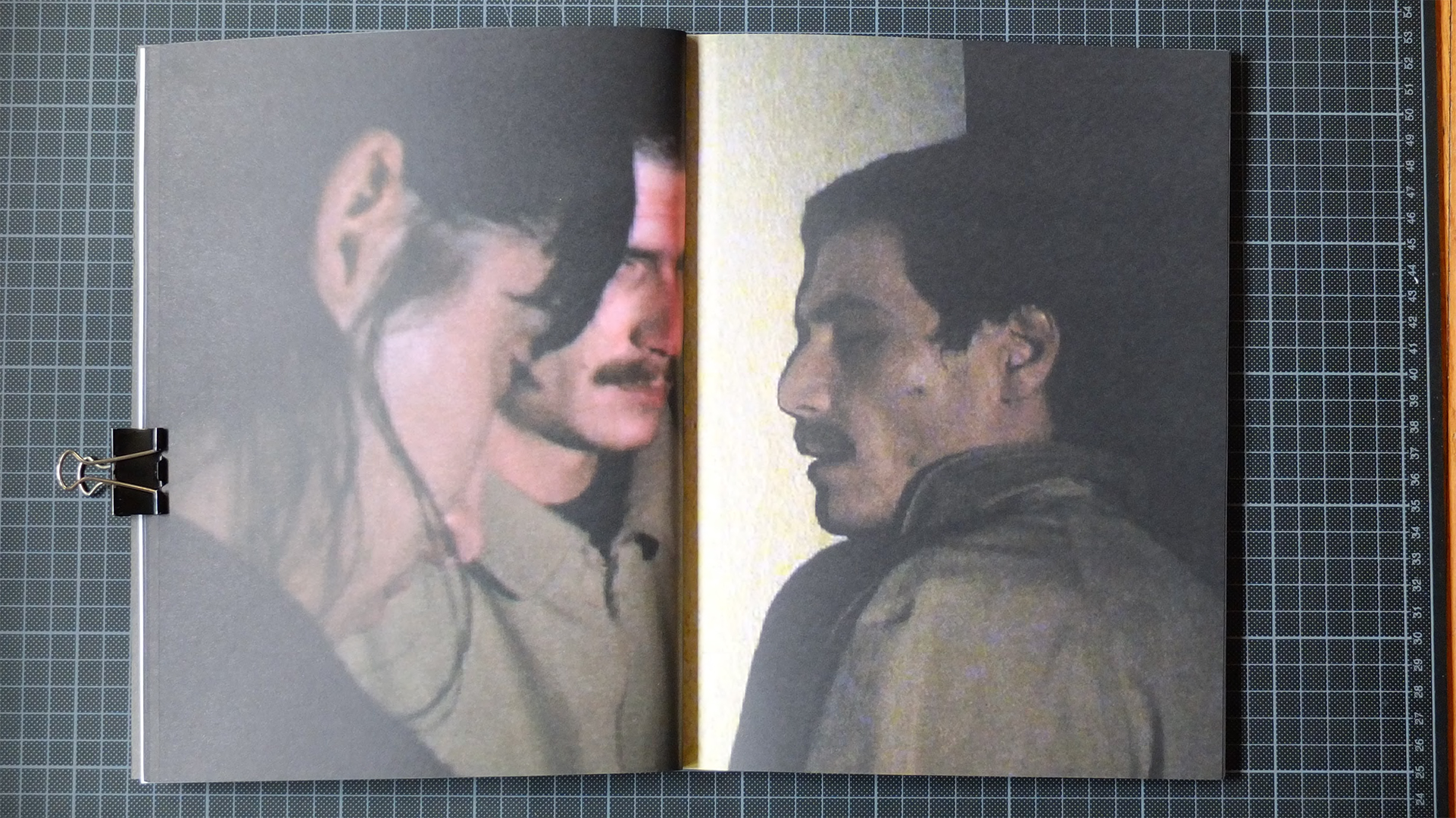

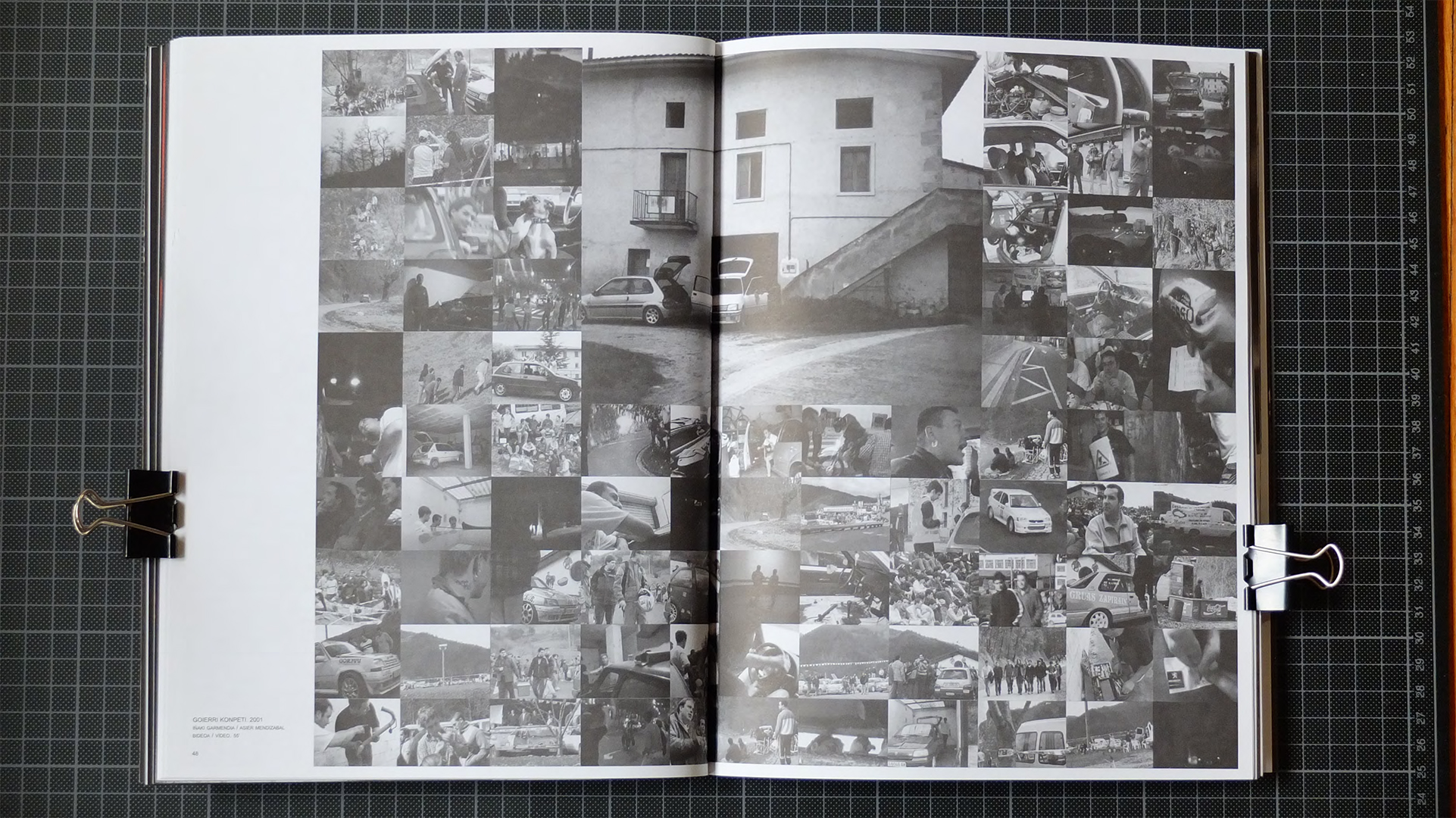

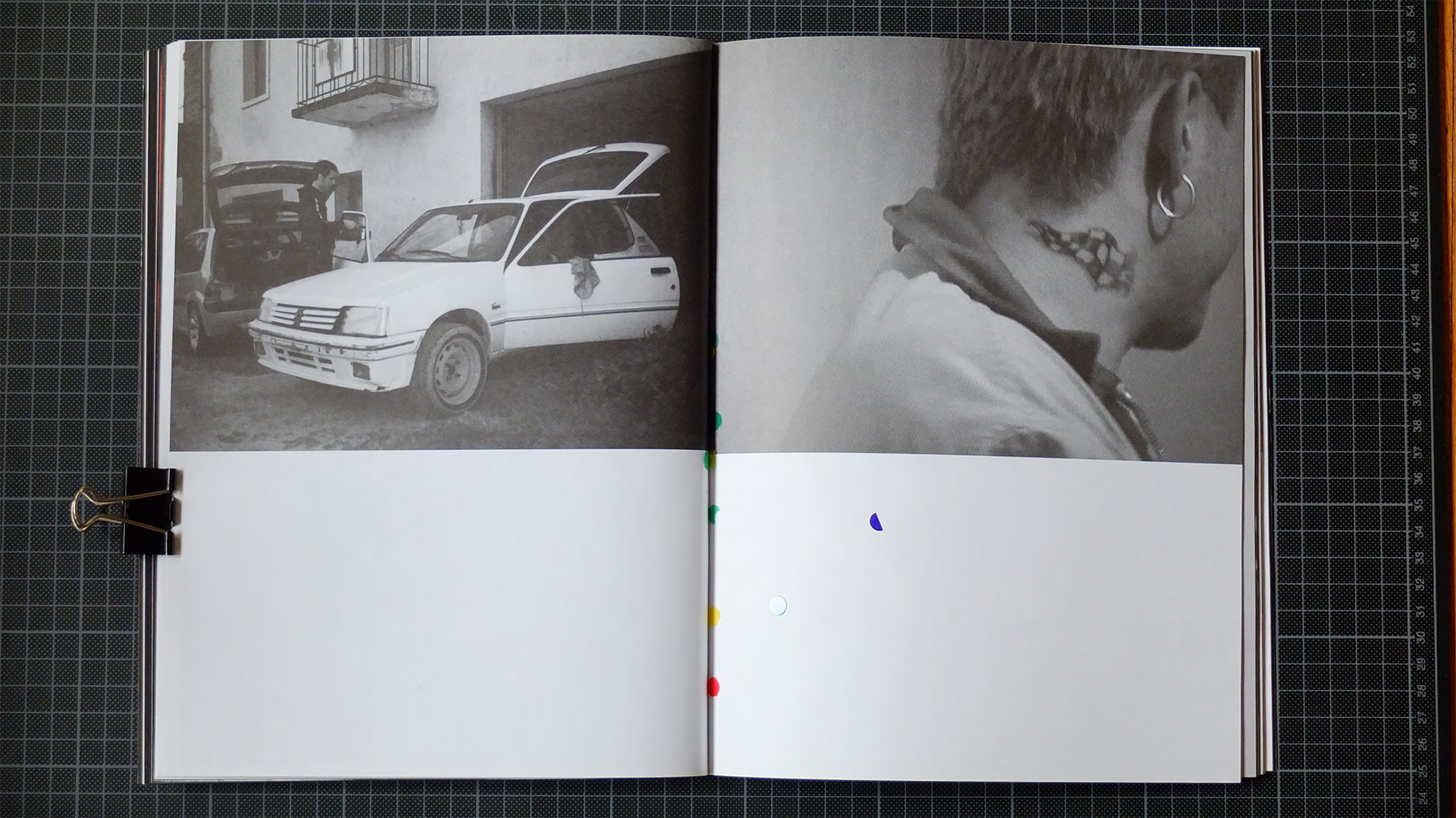

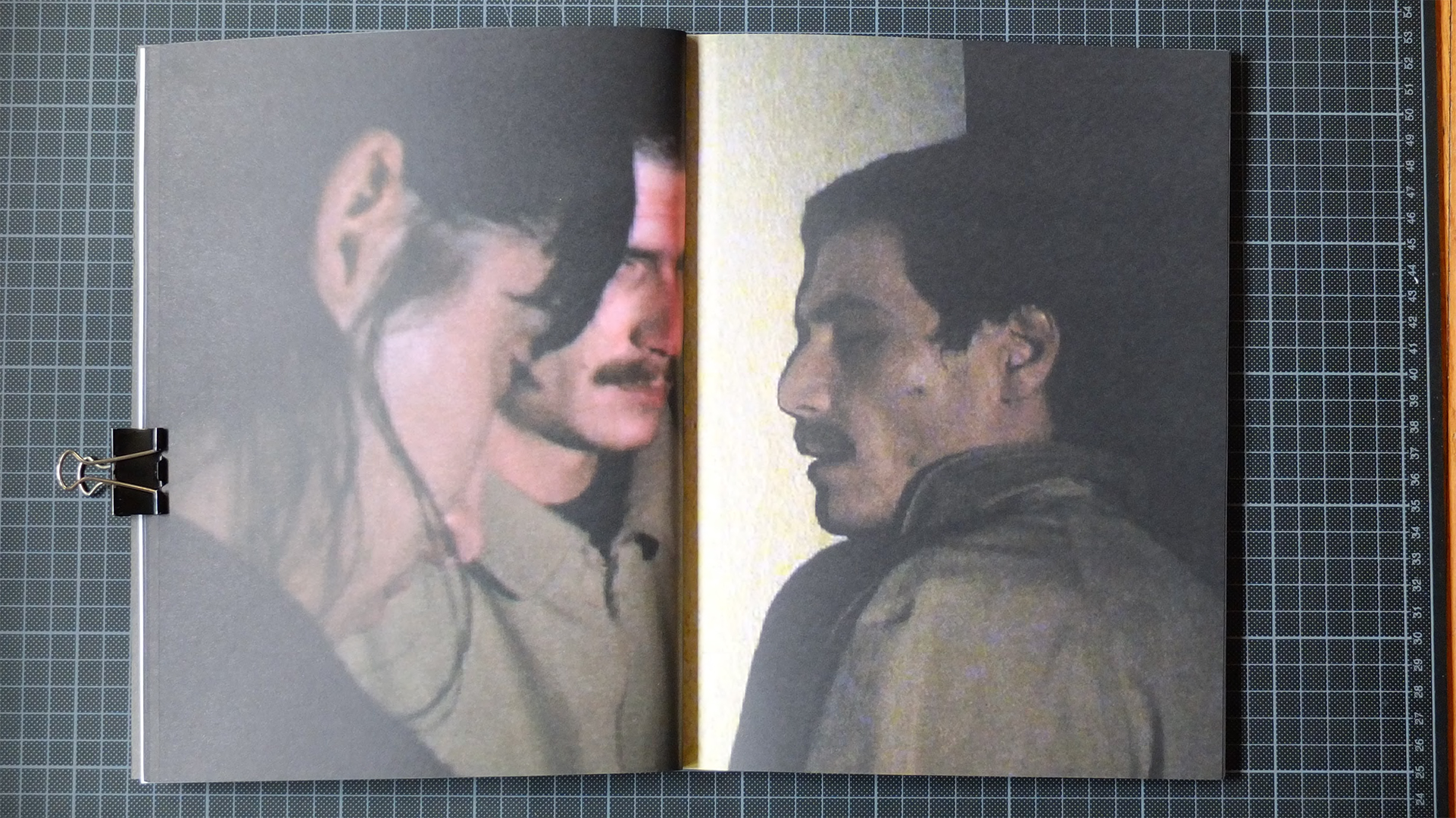

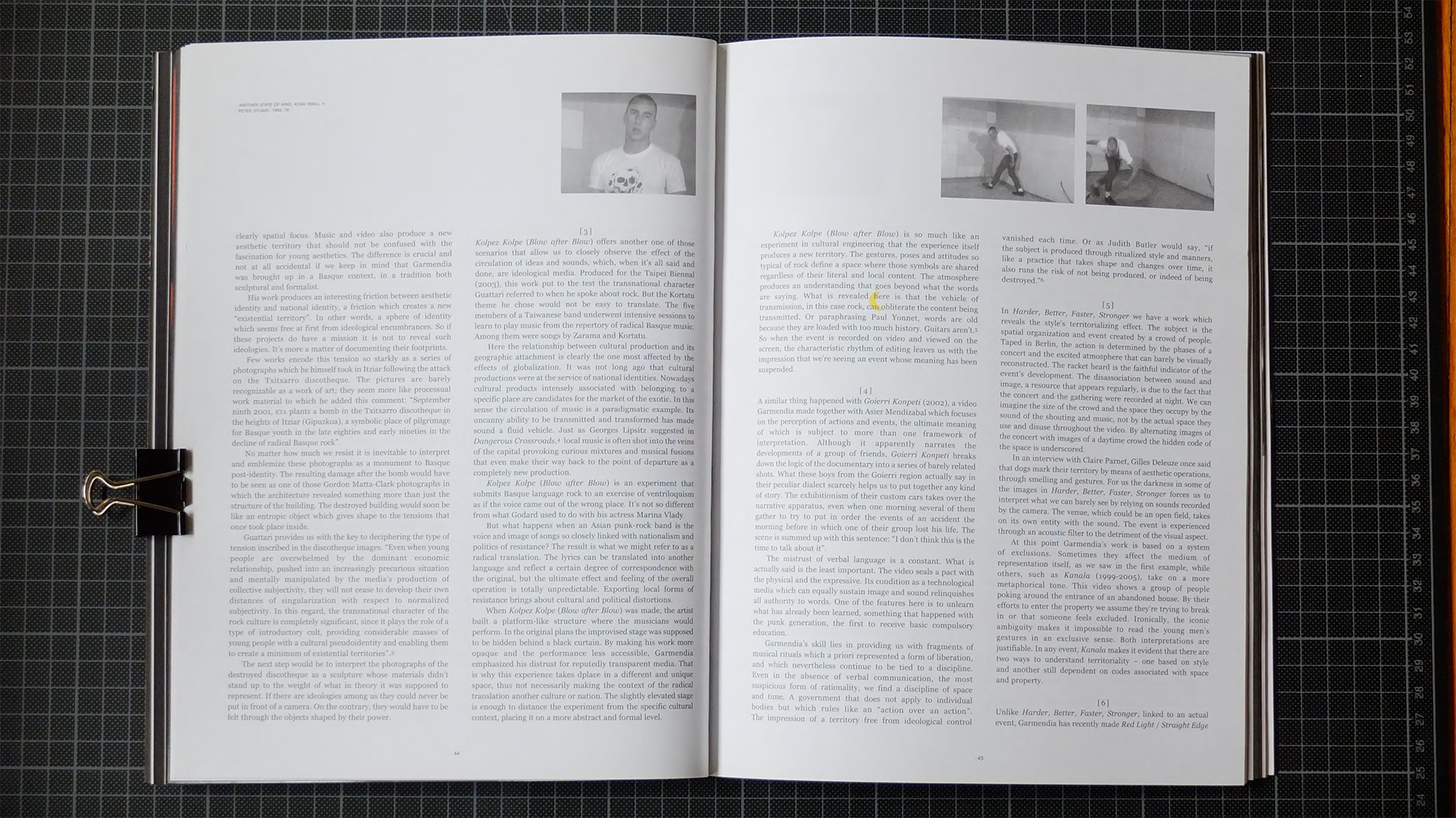

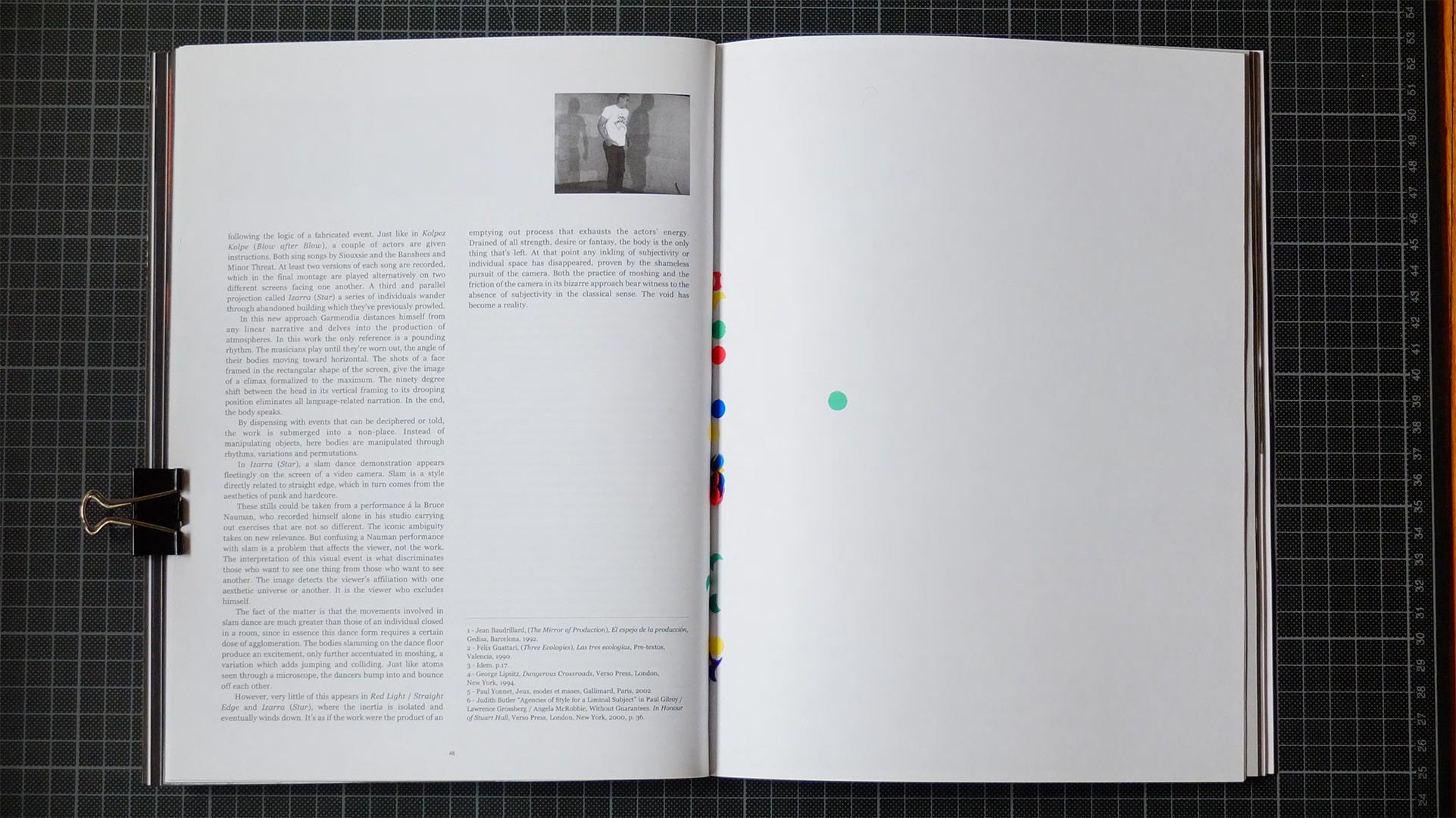

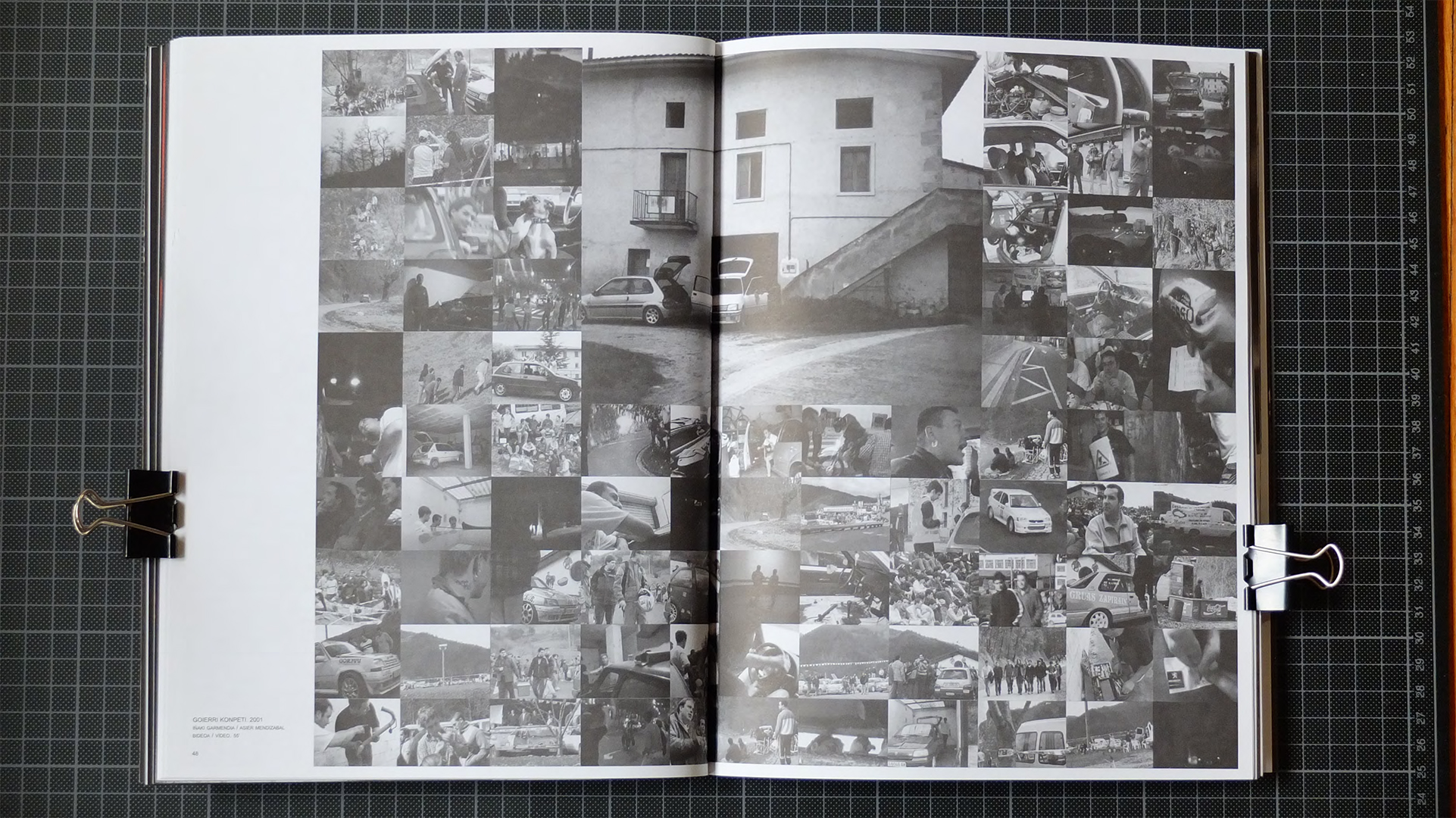

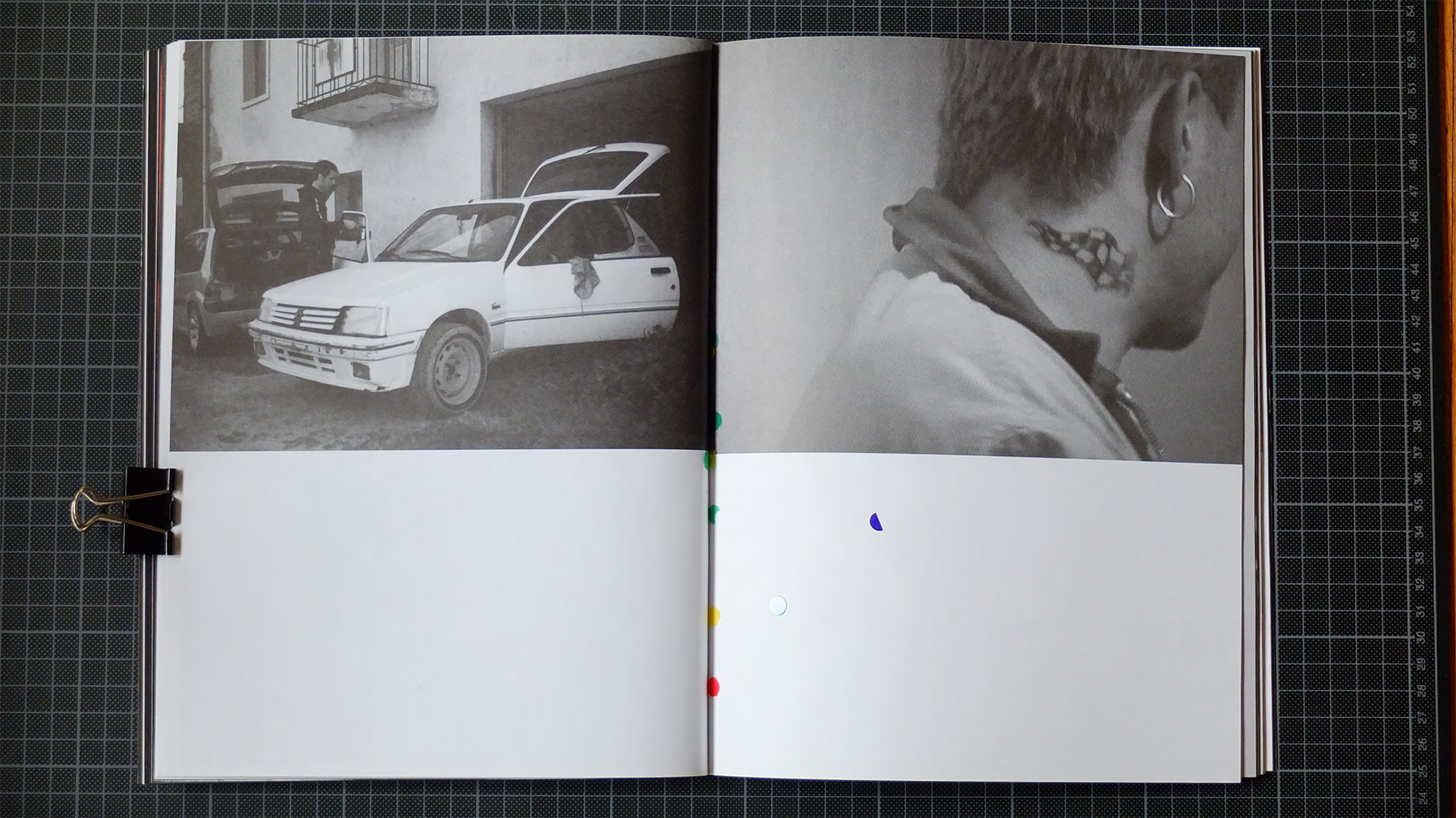

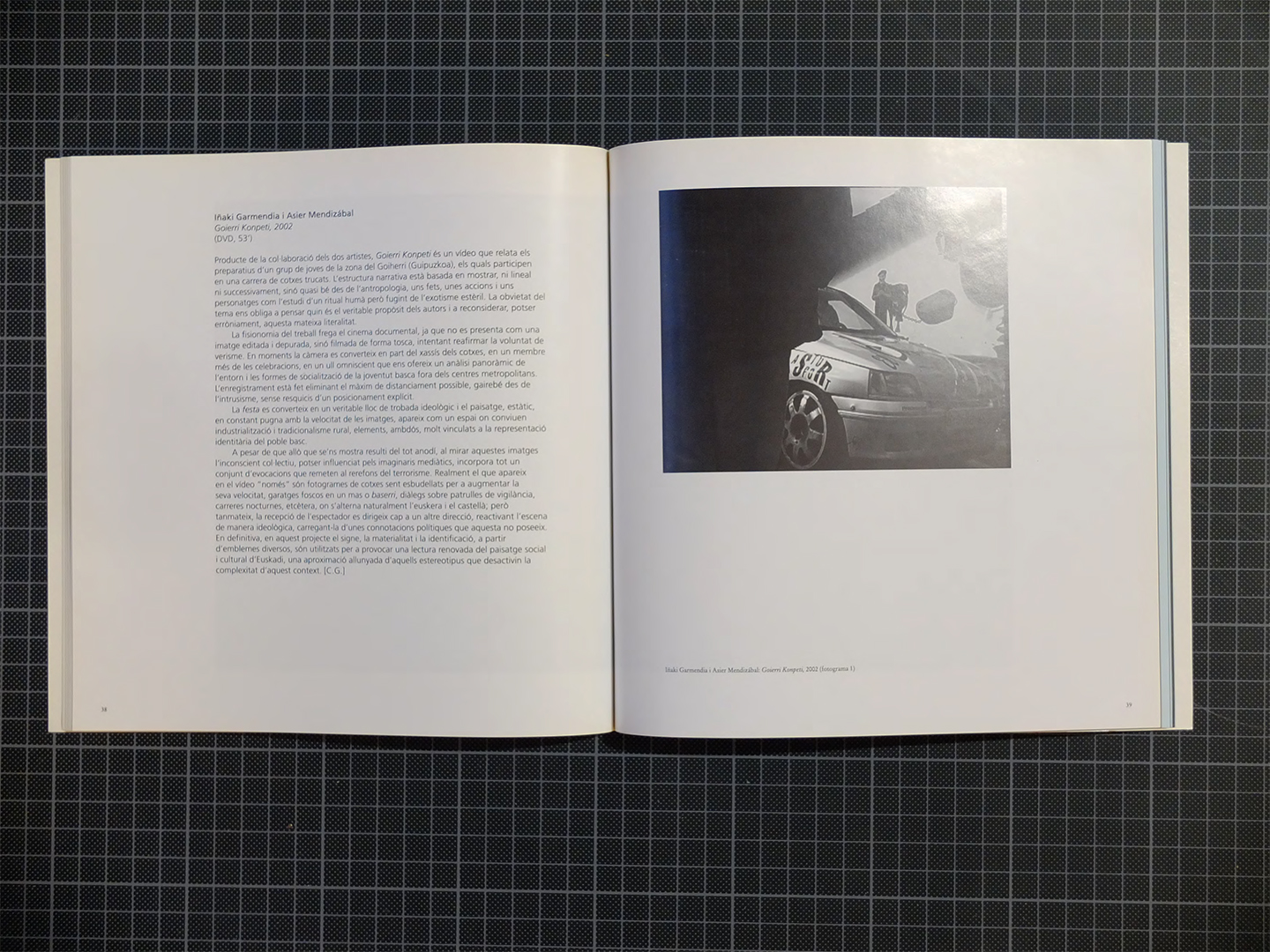

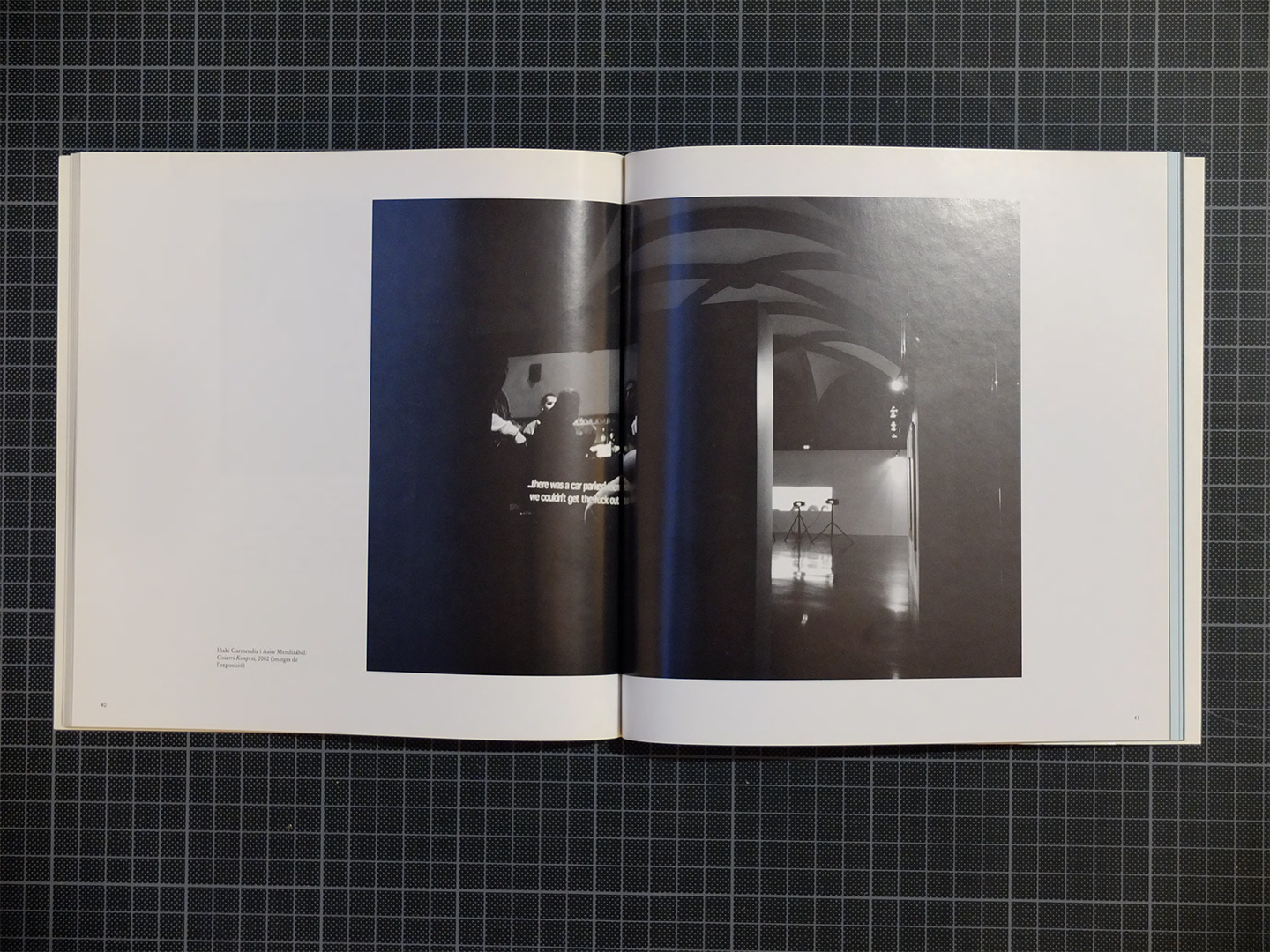

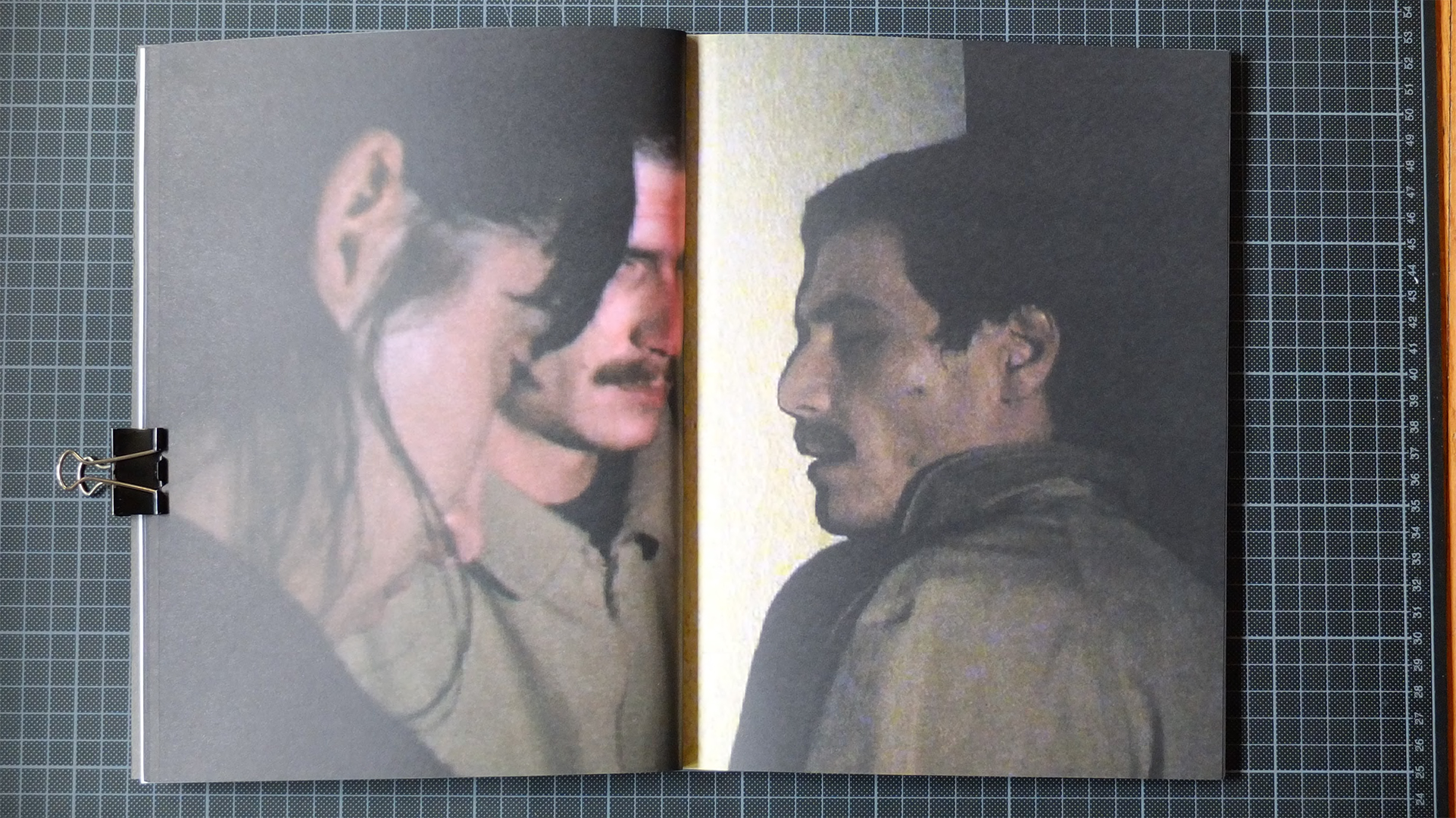

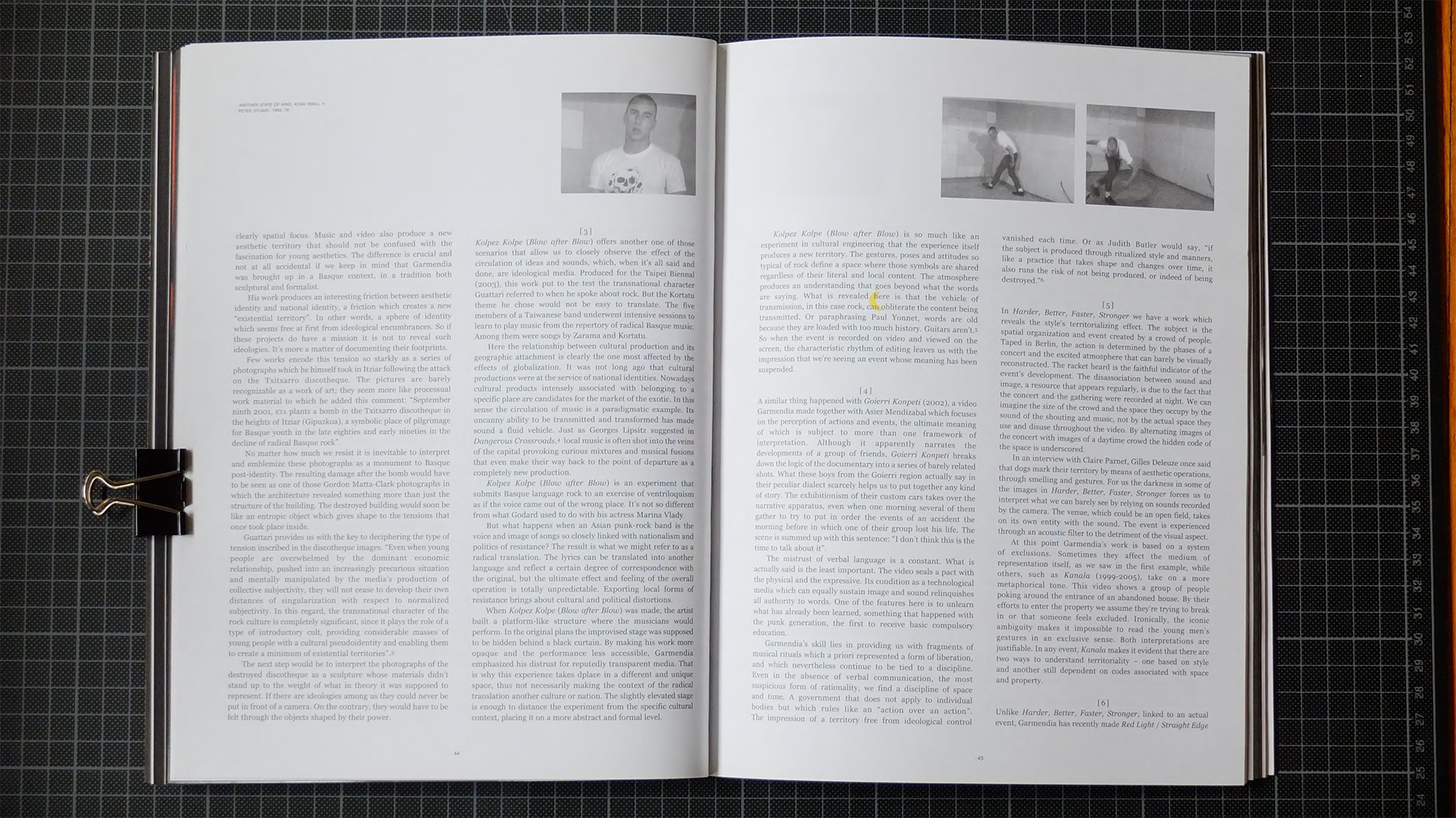

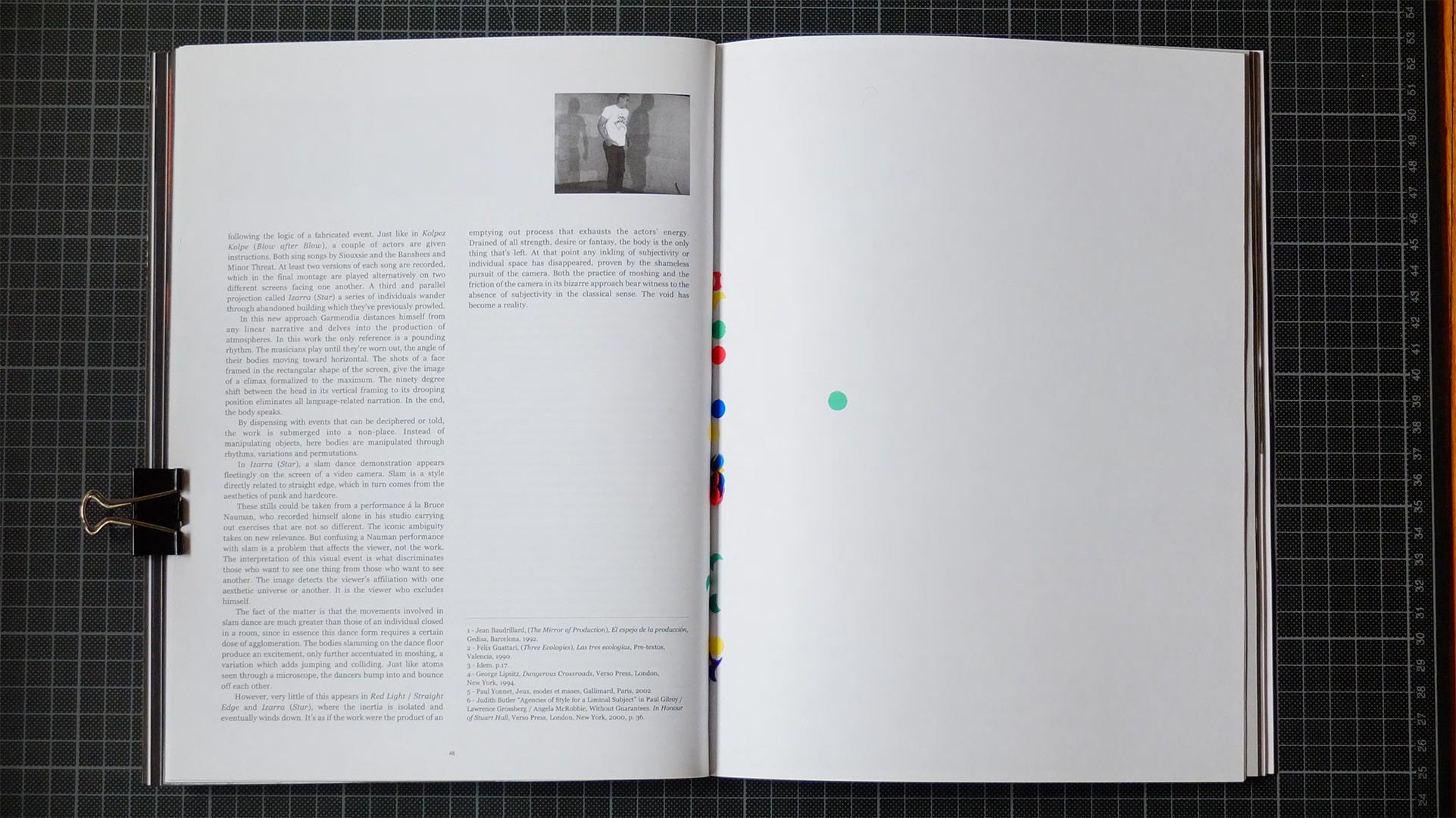

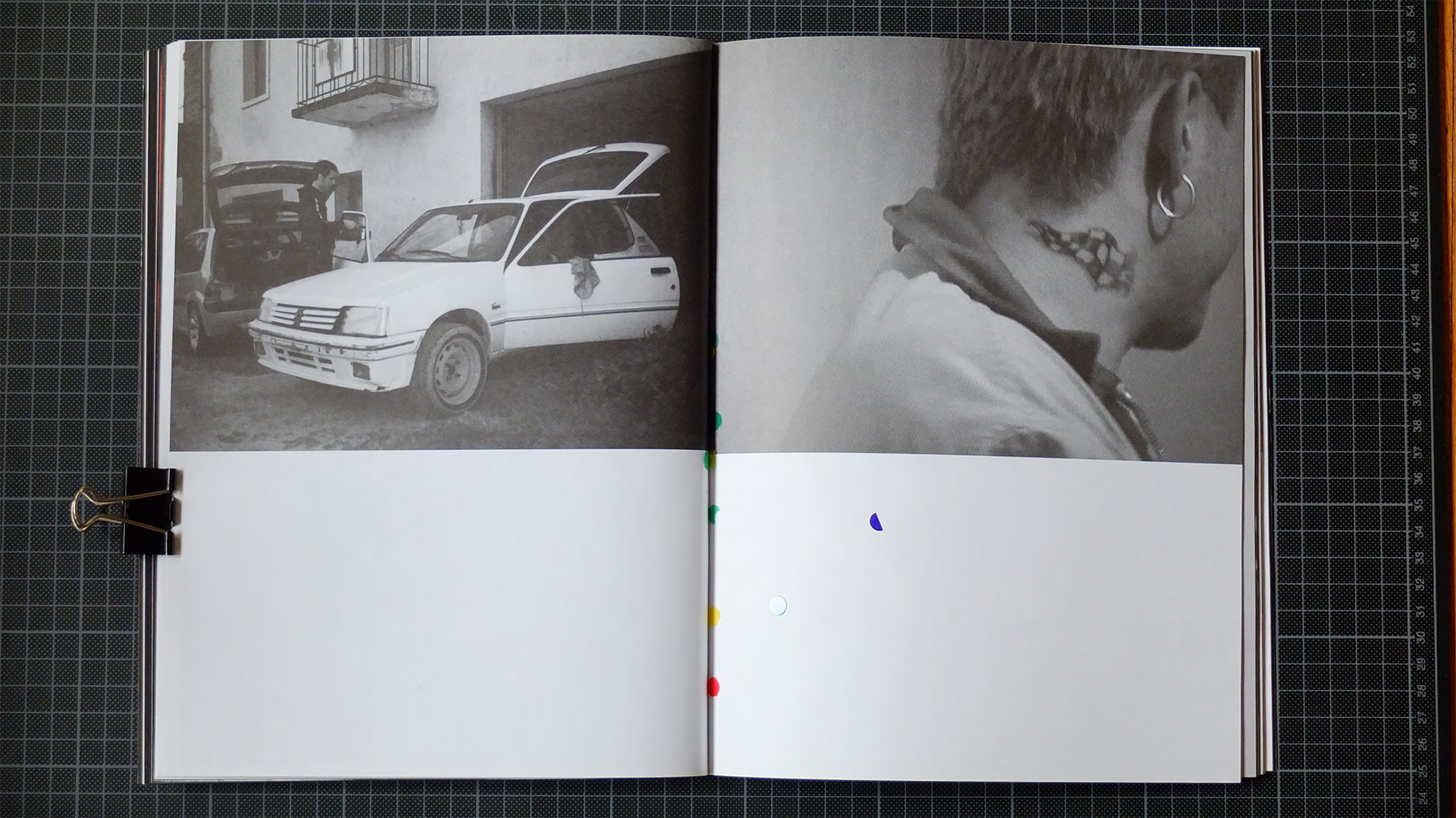

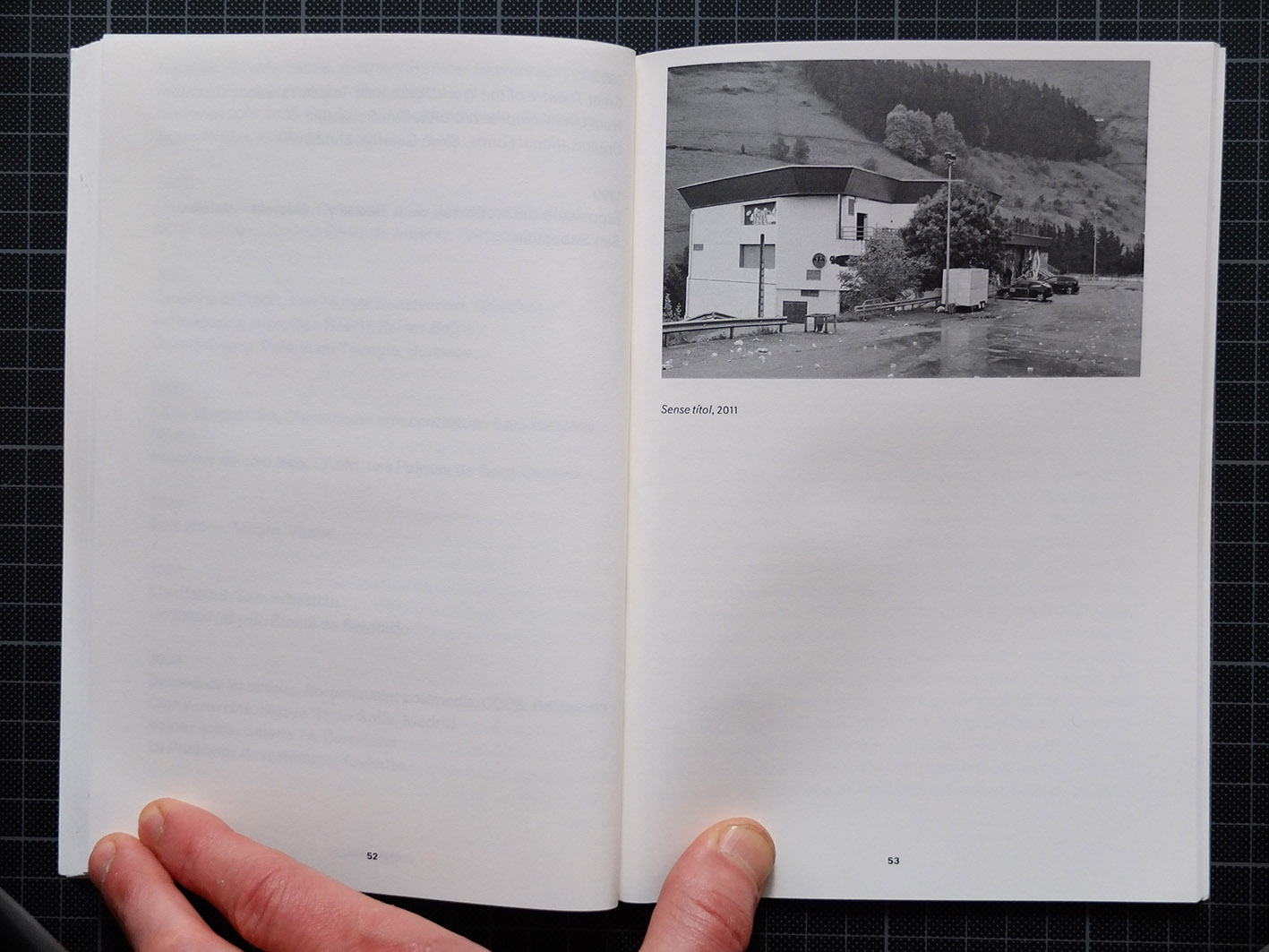

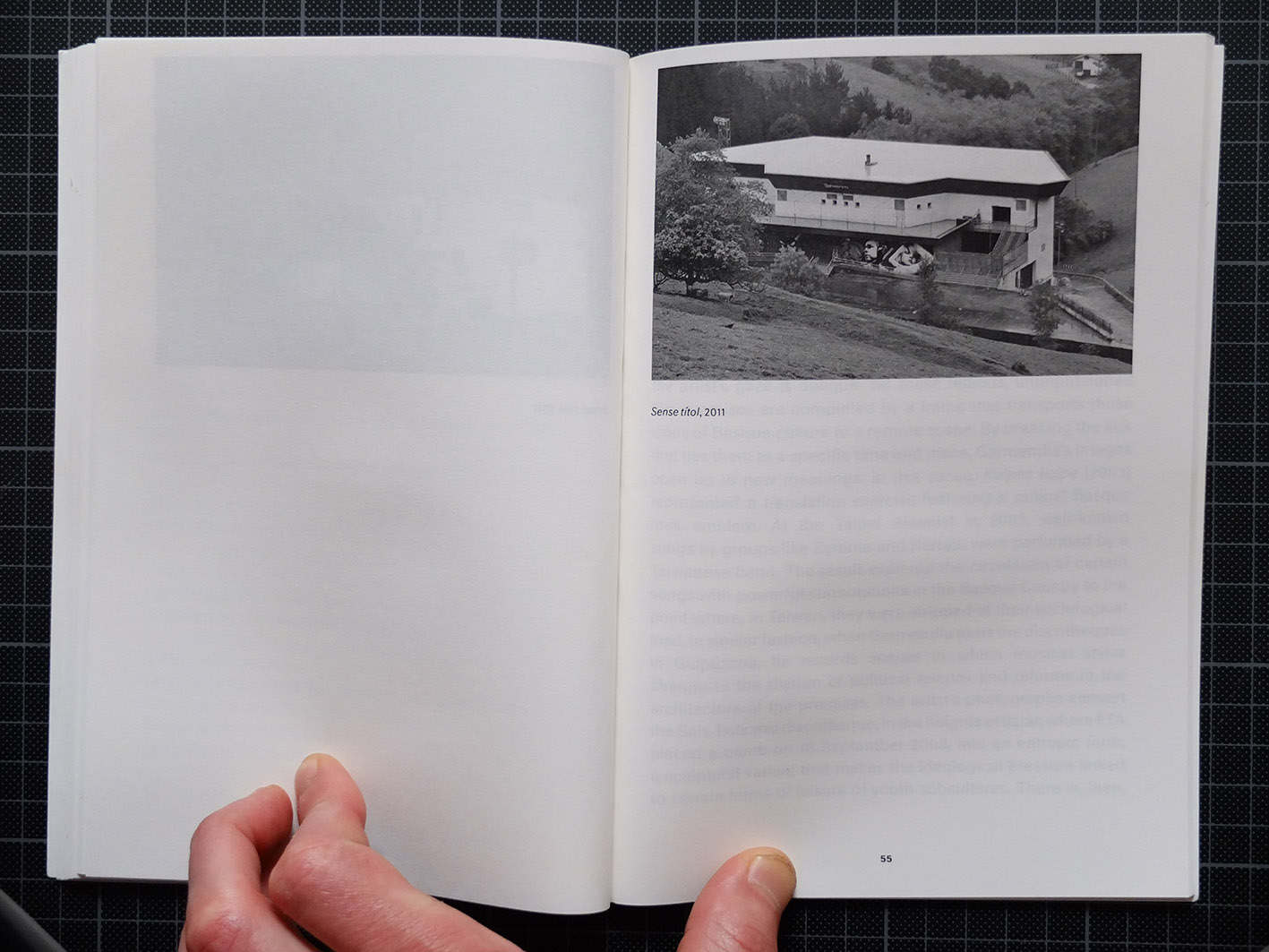

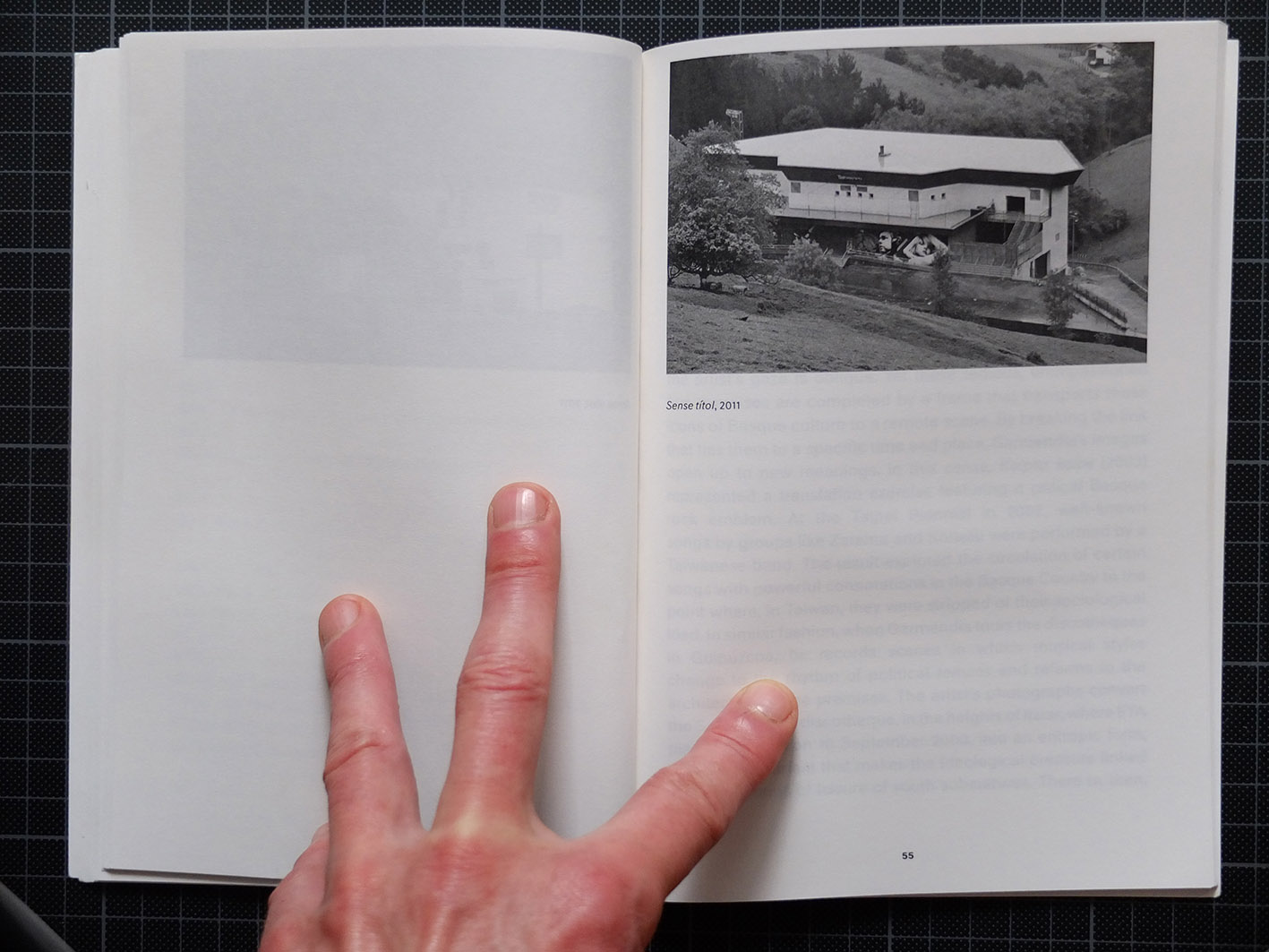

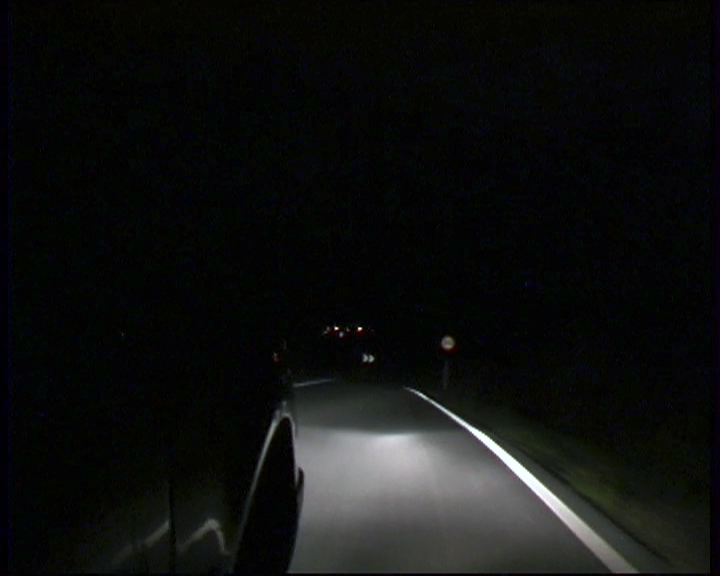

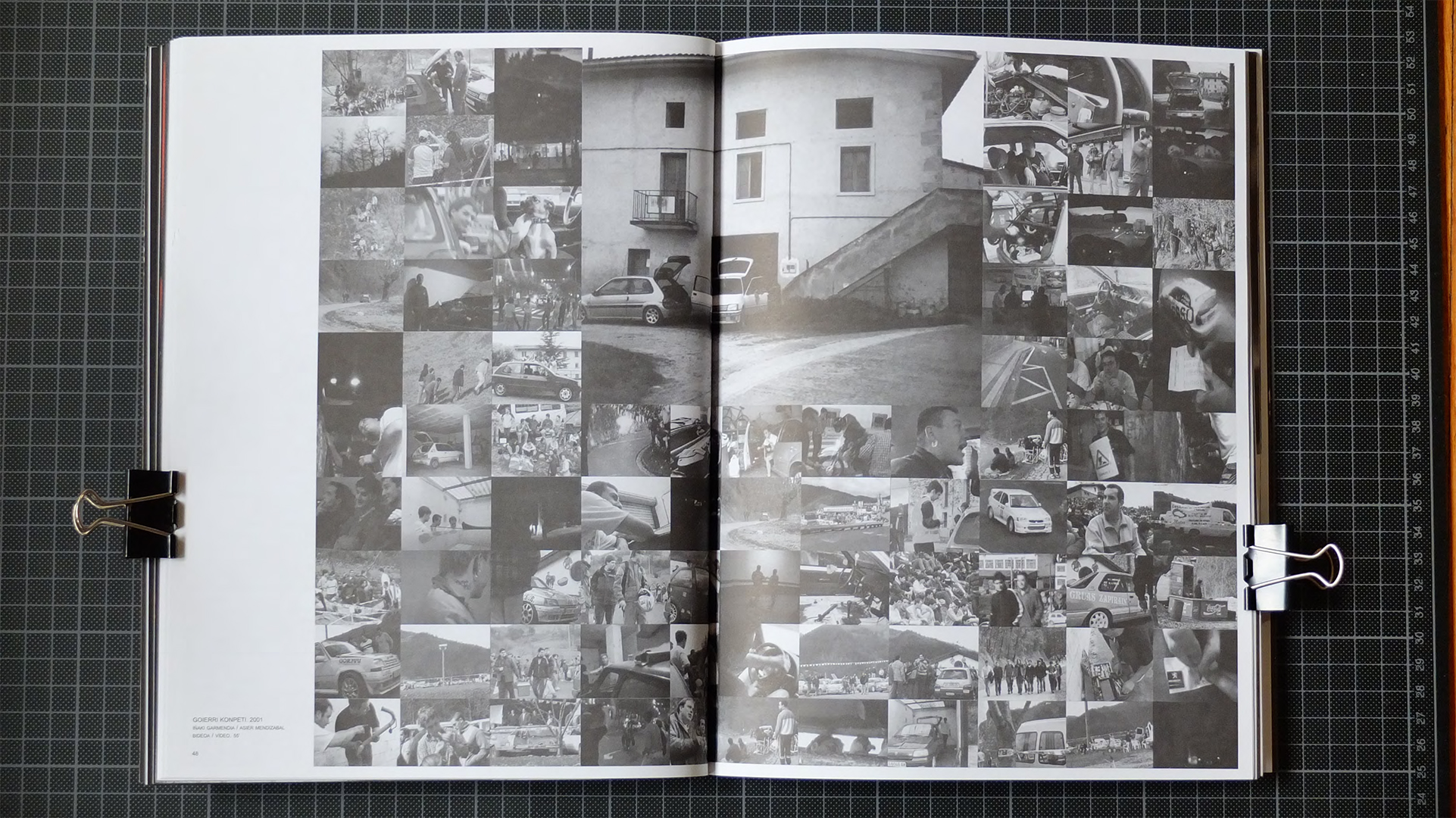

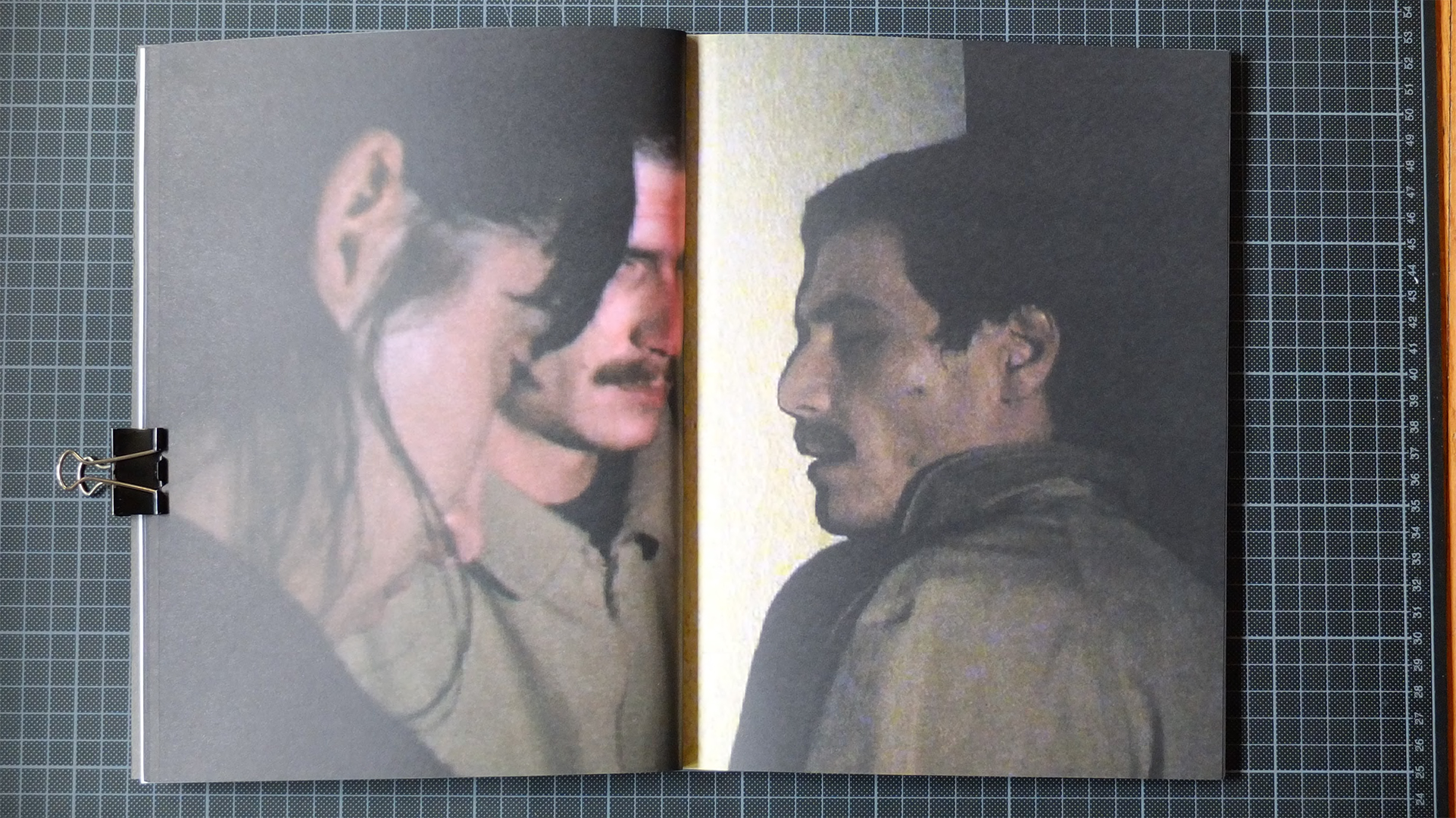

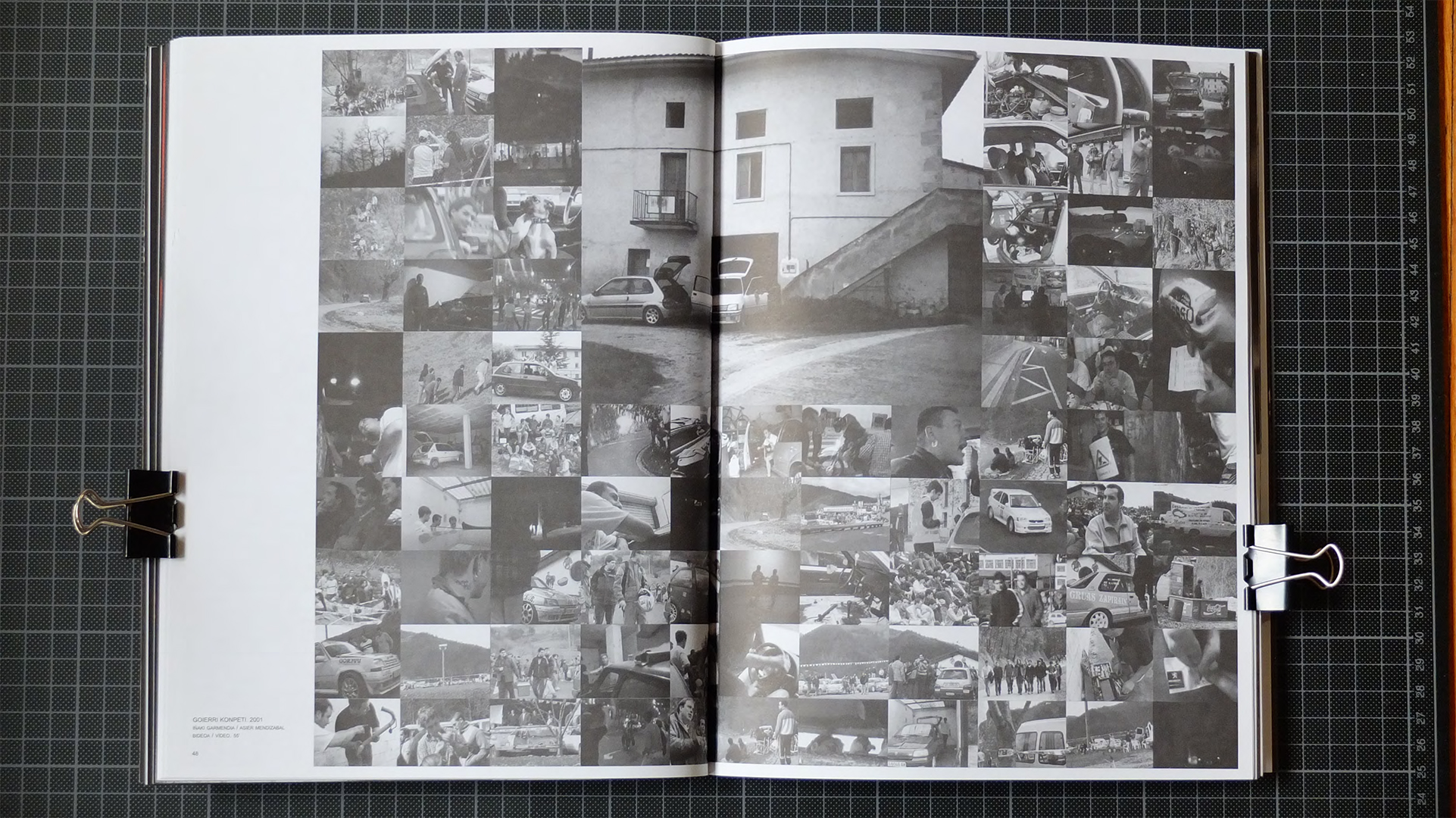

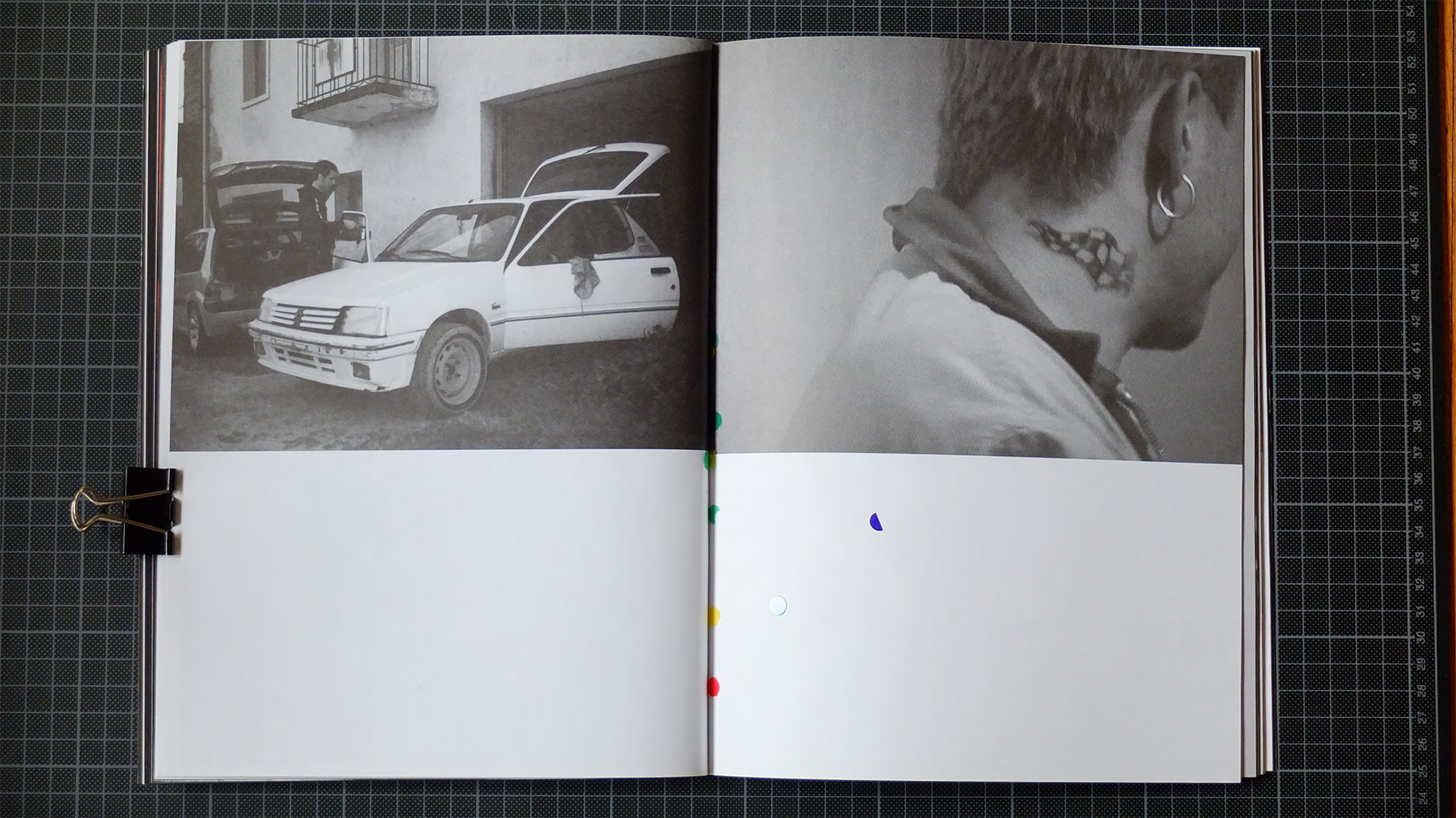

The protagonists in Goierri Konpeti, a group of young men, build their collective identity in the periphery by customising their cars, celebrating rallies and spending endless days driving at full speed. They communicate randomly alternating Basque and Spanish, drifting along whatever the situation asks for or carrying on in the language in which the first sentence of a conversation is spoken, which unconsciously establishes one language as dominant. The film’s subtitles translate this linguistic negotiation into a uniform English, never indicating the power play underlying the cultural cohabitation of the two languages. The video shows therefore its original attempt: to act as a visual artefact within the contemporary art sphere that may help introduce a highly codified peripheral reality. The simplification carried out for the benefit of English speakers reinforces Stilinović’s thesis suggesting that a worldwide exchange of the contemporary must happen in English. However, some peripheral narratives were more easily assimilated than others during this period. The fact that they were mediated by a perfect translation into English was not enough.

The authors of this work, Iñaki Garmendia and Asier Mendizabal, had obvious motives to be interested in making a documentary about a group of young men from Goierri, being the home region of both artists. This is an area that, in a way, was also immersed in its own normalisation processes at the time of the filming, marked —among other determinant aspects— by ETA’s ceasefire in 1998 and its interruption fourteen months later, in December 1999. The film, however, barely mentions these intentions, which hide behind a “methodology of the minimum possible distance”, as indicated by Miren Jaio in her review of the film En compañía de hombres (1993), published in Mugalari, the cultural supplement of the newspaper GARA.

The “embedded” camera crosses the valley in Arkaitz’s car, becoming invisible as everybody shares drinks, cigarettes and dinner; it captures the work of assembling and disassembling the pieces in the ground floor garage they rent in a baserri, filming the aimless comings and goings without cuts. However, as Miren Jaio points out in her text, it turns out that distance zero is not possible in this context. It becomes clear as we see the artists holding the little pet that accompanies the group at all times, designing the paintwork and patterns on one of the cars, and sharing unforeseen experiences in the desire to challenge the line demarcating the road across the well-known landscape.

Related bibliography

→ Front Line Compilation : “Goierri konpeti” : Iñaki Garmendia y Asier Mendizabal. San Sebastian, Donostiako Arte Ekinbideak : Kutxa Aretoa, 5 July 2002.

→ Formen der organisation. Ljubljana, Galerija Skuc, 28 November 2002 – 15 January 2003; Leipzig, Galerie der Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, 11 April – 10 May 2003; Lüneburg, Universität Lüneburg, Kunstraum, 8 – 24 July 2003

Ponencia de María Soledad Álvarez Martínez que aborda una revisión de la escultura vasca partiendo de la actualidad de la plástica vasca en el cambio del milenio. Cita a Iñaki Garmendia como representante de una generación emergente de creadores que tienen como herramientas nuevos medios [pág. 901].

→ Kolpez Kolpe. Barcelona, Galería T4, 19 November 2003 – 24 January 2004.

→ Kolpez Kolpe. Barcelona, Galería T4, 19 November 2003 – 24 January 2004.

→“Goierri konpeti” : Iñaki Garmendia y Asier Mendizabal. Bordeaux, Galerie du Triangle, 5 – 20 June 2003.

→ Després de la noticia : documentals postmèdia. Barcelona, CCCB-Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, 23 July – 2 November 2003.

→ Cine y casi cine. Madrid, MNCARS-Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 13 November – 19 December 2003.

Iñaki Garmendia. Kolpez Kolpe. [Press release]. Barcelona : Galería_T4, 2003.

Front Line Compilation. San Sebastian: Donostiako Arte Ekinbideak, 2003, pp. 27; 54.

Ainara Gorostitzu. “Euskal artearen manifestazioa”, Berria, Andoain, 09/06/2004, pp. 40-41.

Press release on Basque artists in Manifesta 5. Includes brief interview with Iñaki Garmendia, “Proiektu hau Euskal Herritik at lantzea premiazkoa zen”.

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

→ Underdox : dokument und experiment München. Munich, Filmmuseum; Werkstattkino; Theatiner Filmkunst, 2 – 8 October 2008.

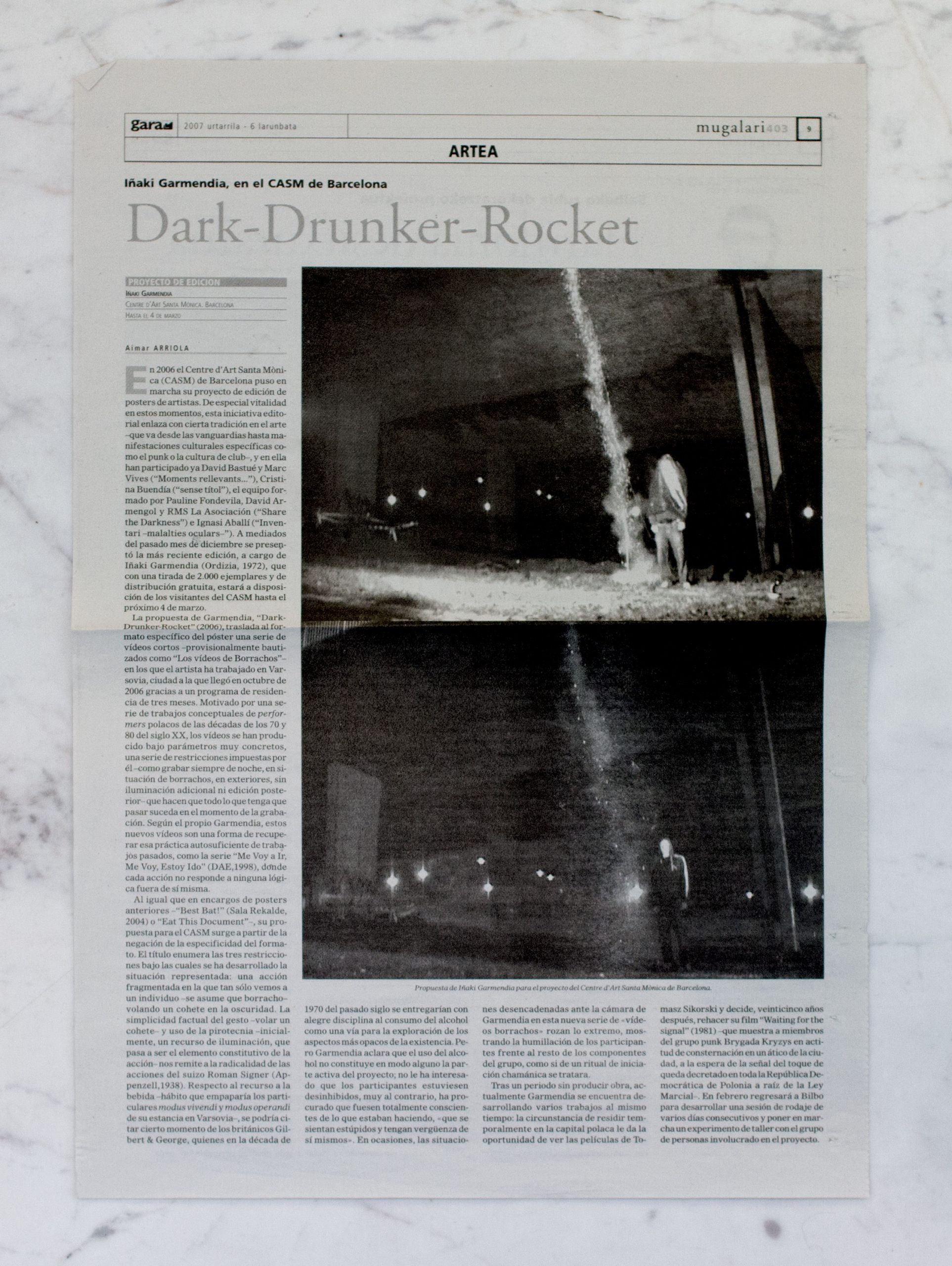

Artículo de Aimar Arriola sobre el proyecto de edición de posters de artistas del Centre d`Art Santa Mònica de Barcelona, para la que Iñaki Garmendia presenta Dark-Drunker-Rocket, que según el autor “traslada al formato específico del póster una serie de vídeos cortos –provisionalmente bautizados como ‘Los vídeos de borrachos’– en los que el artista ha trabajado en Varsovia.” Corresponde a la residencia que el artista realiza en 2006 en el Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Varsovia.

La condició de la imatge. [Exh. cat.]. Lleida, Institut d’Estudis Ilerdencs, cop. 2010.

Exhibition catalogue for La condició de la imatge, Gothic Hall, IEI-Institut d’Estudis Ilerdencs, Lleida (17/12/2009-14/02/2010) with works by Carles Guerra, Vlad Nancă/Asier Mendizabal and Iñaki Garmendia. Includes still image and photo of screened work, Goierri Konpeti (2001) with Catalan text on the piece by curator Carlota Gómez.

“Iñaki Garmendia, en Arco”, El Diario Vasco, San Sebastian, 18/02/2011.

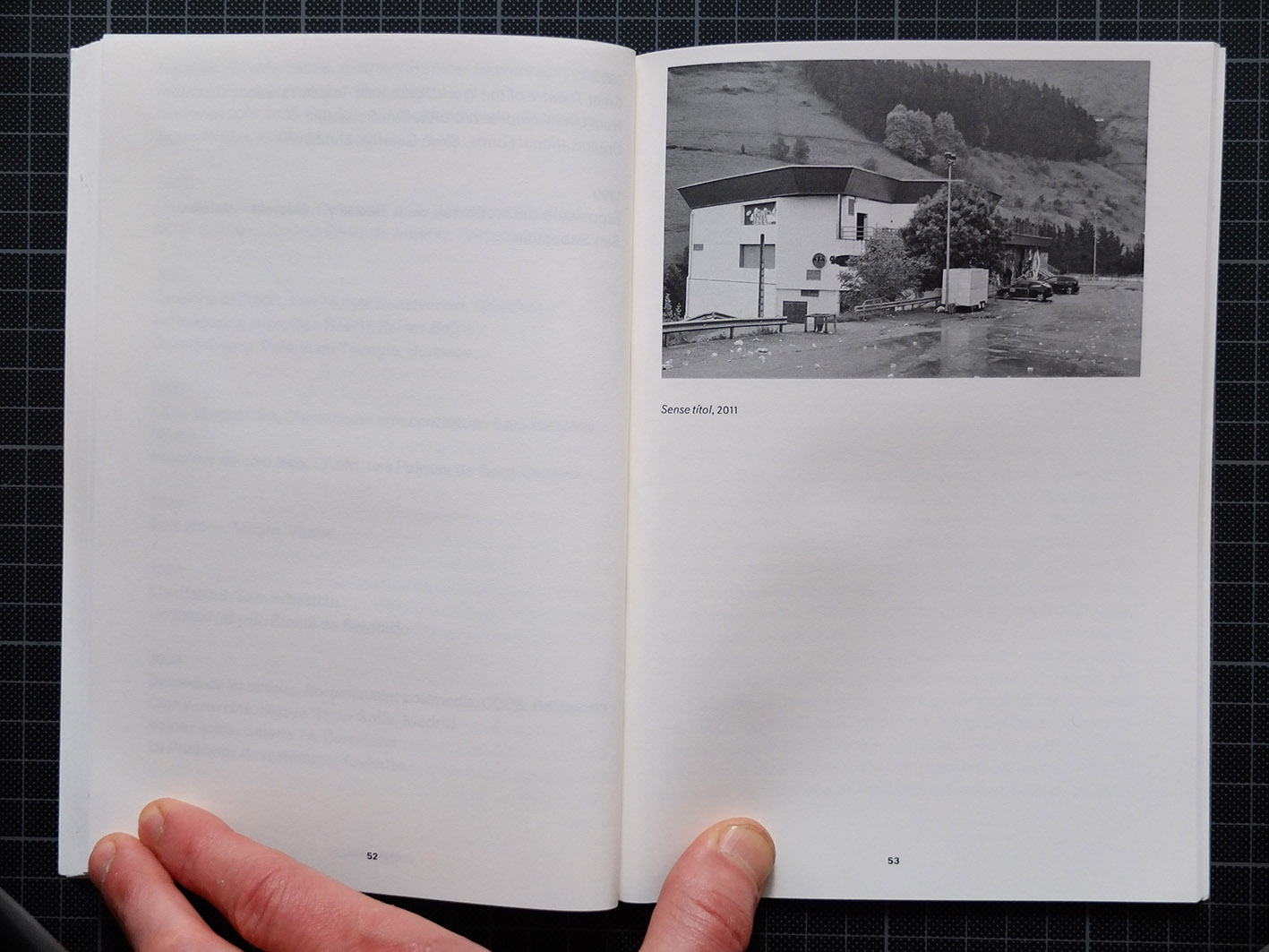

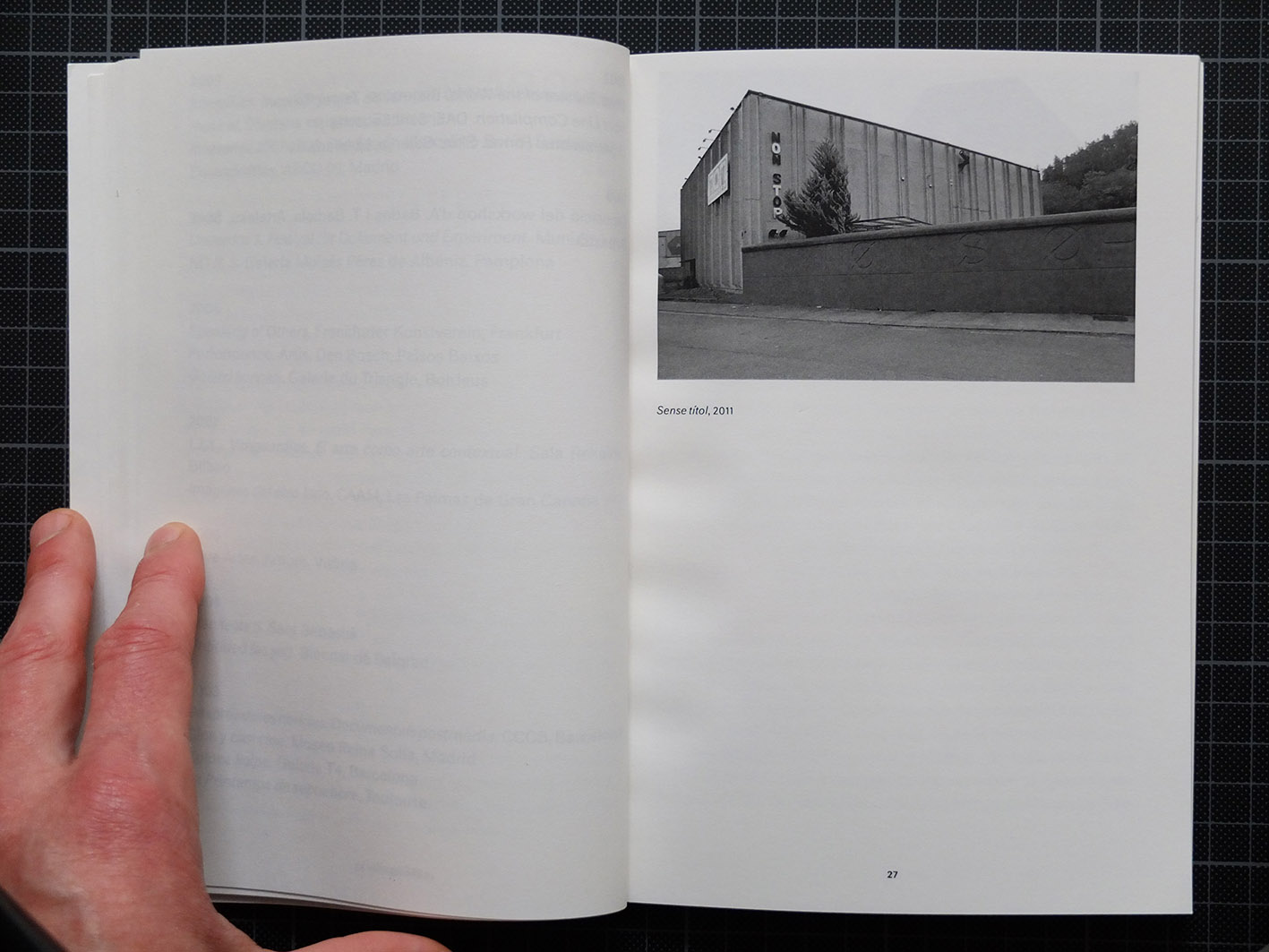

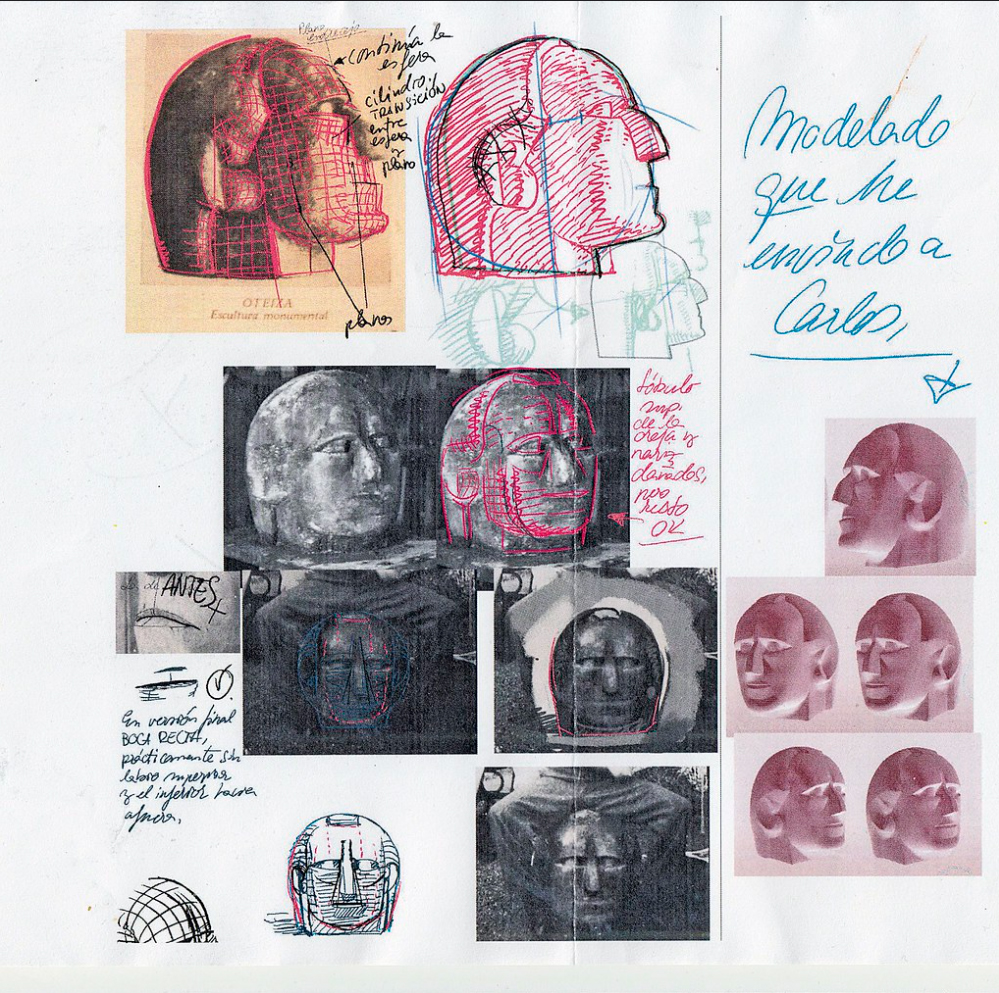

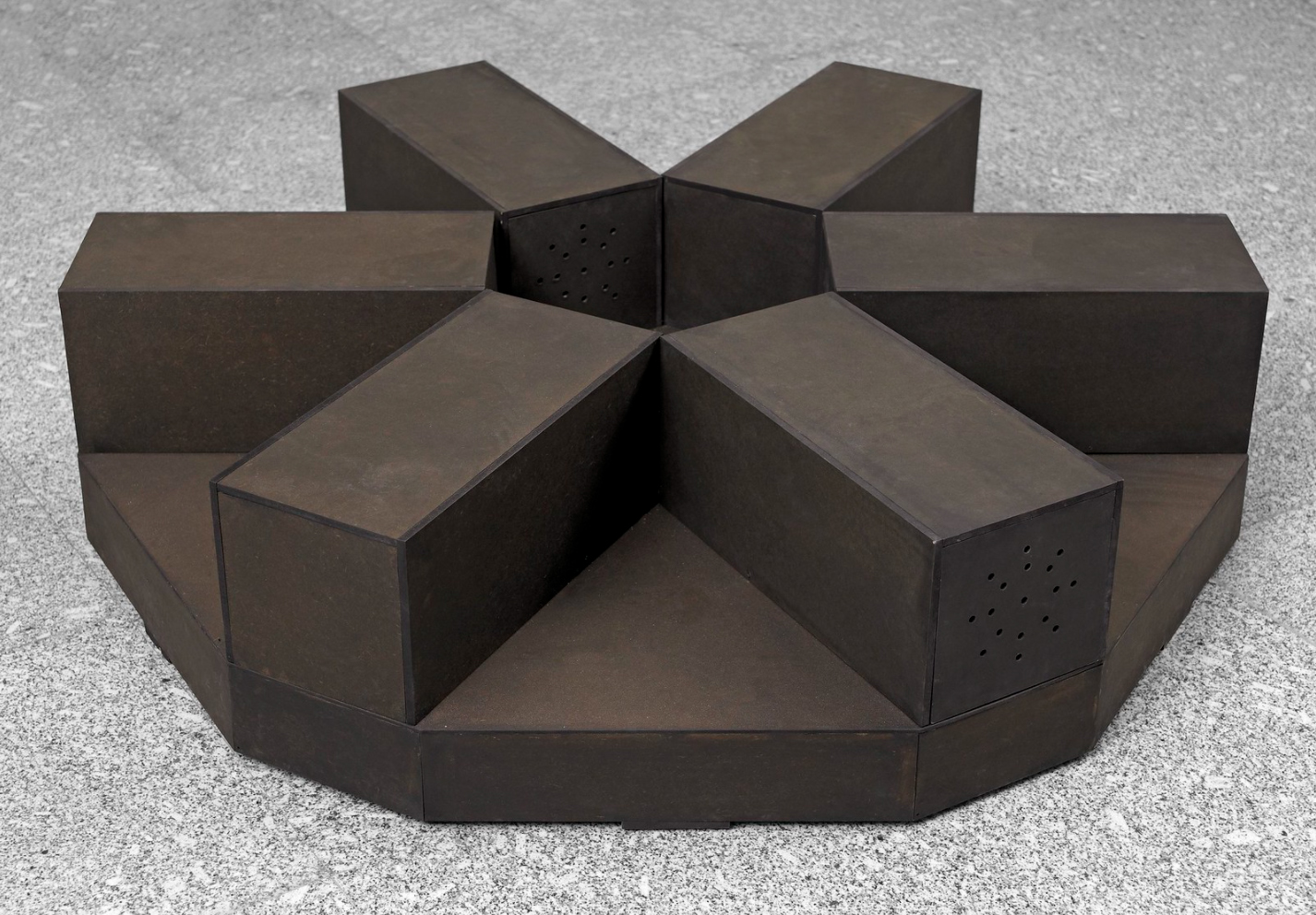

Press release on Iñaki Garmendia at ARCO, Madrid, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, Garmendia presented the sculpture Sin título (Seis picos), which according to the artist was “a reconstruction of a work by Robert Smithson, enlarged to three times its size, built as a single module using loudspeakers incorporating sound. (…) One of the biggest references in my work is everything that relates to (underground) suburban music”.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

Pablo Marte. «Sector Conflictivo. #02: Iñaki Garmendia», Basilika. Podcast, 85 min. 31 sec.

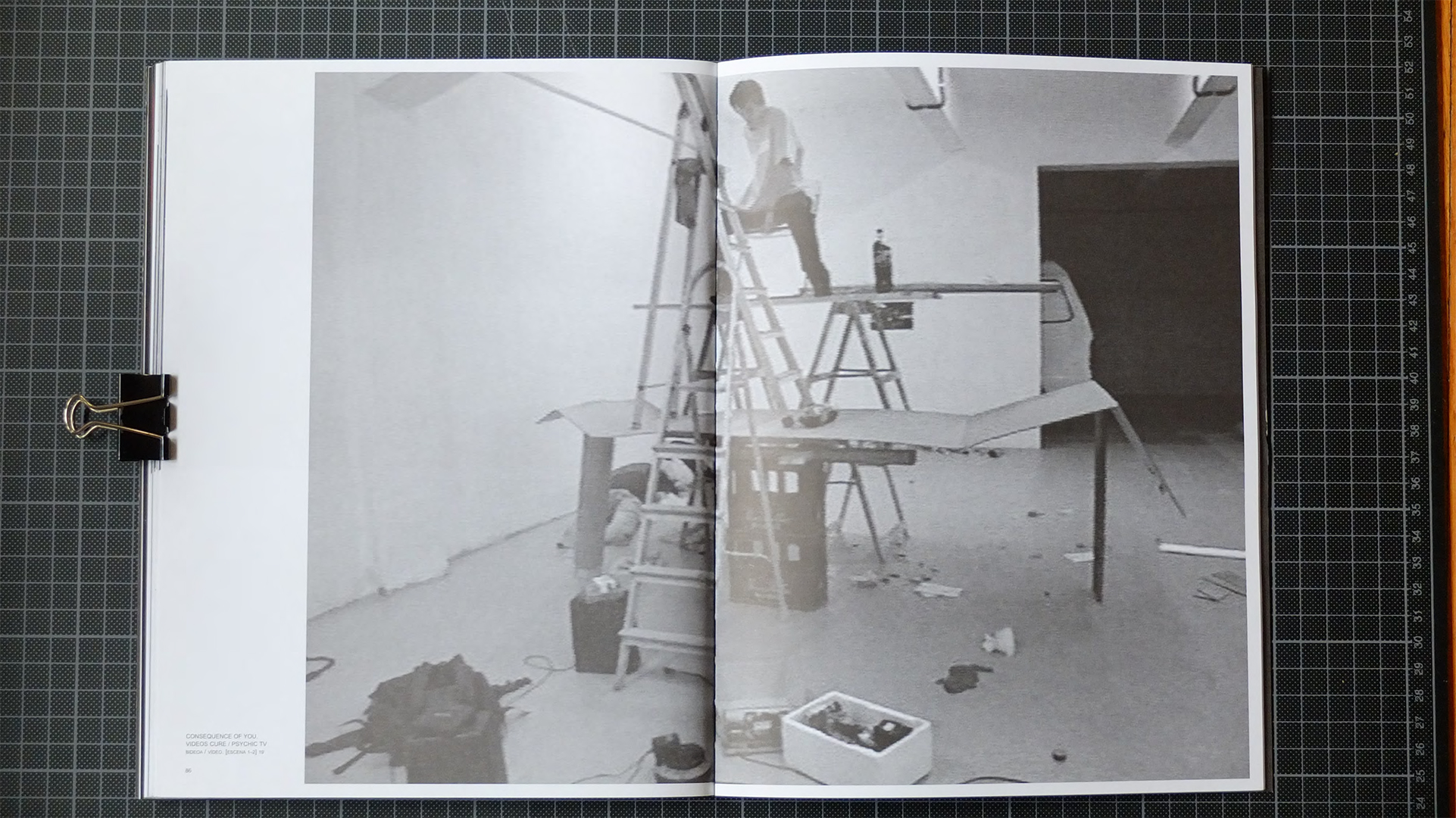

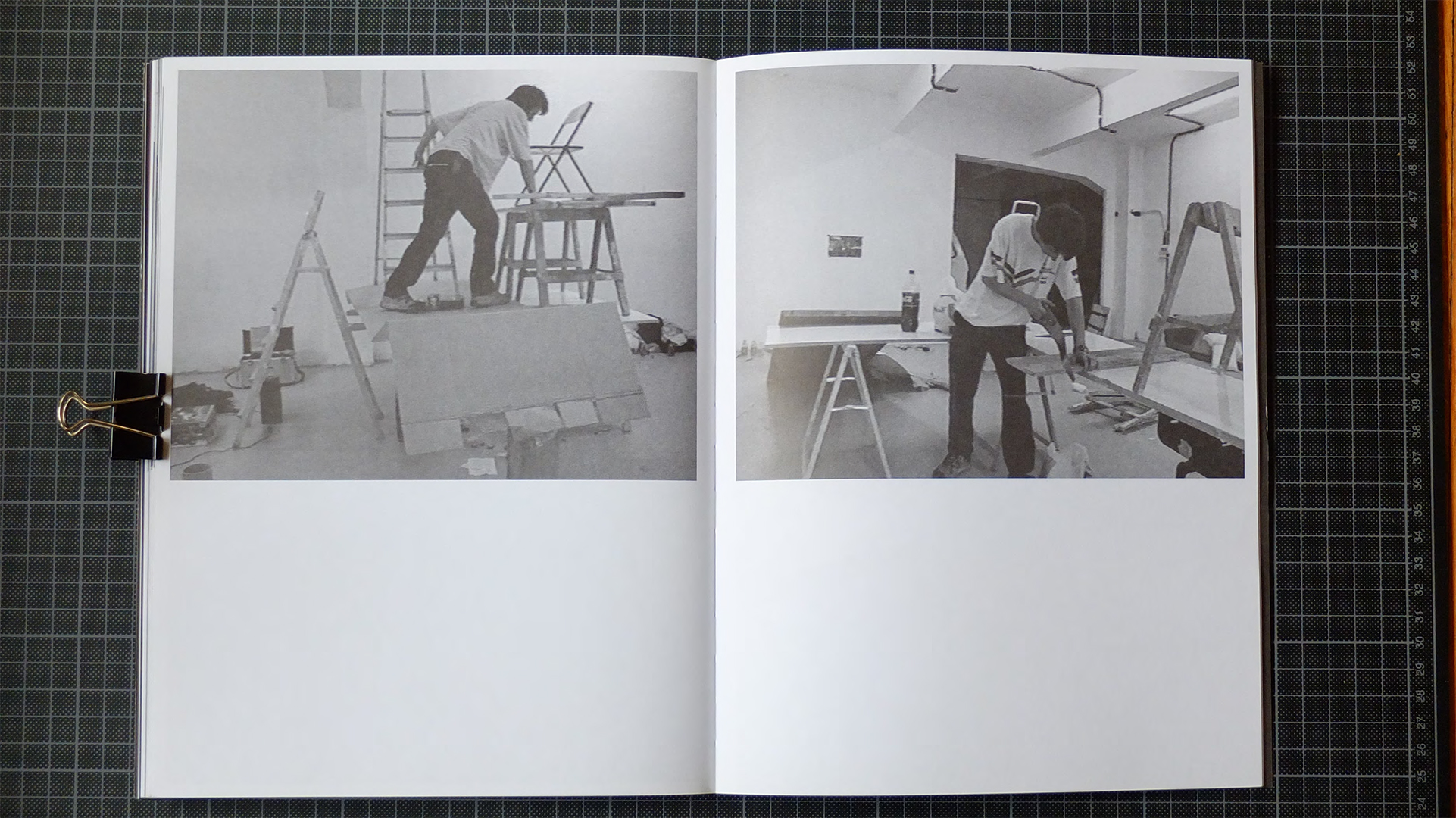

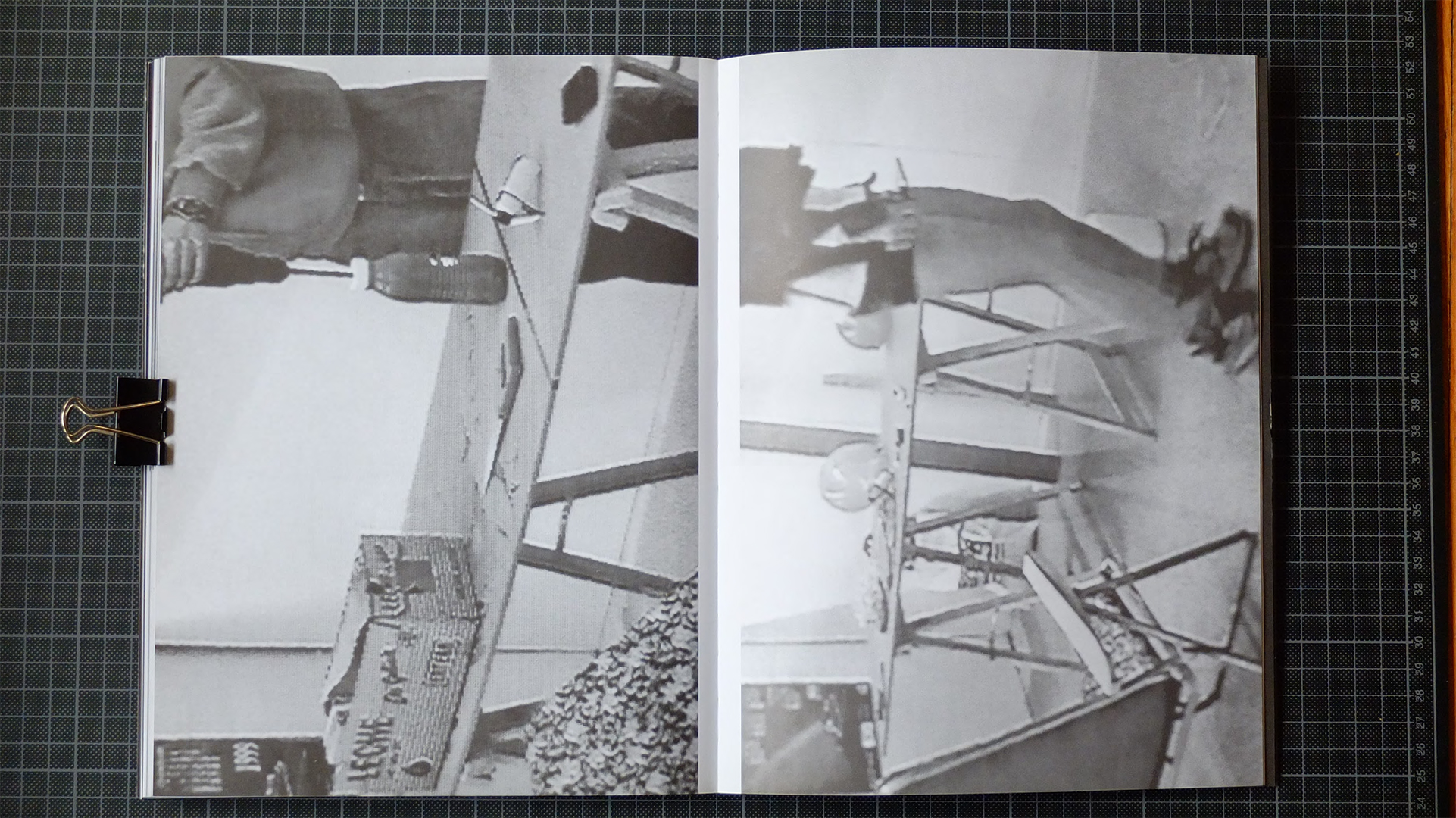

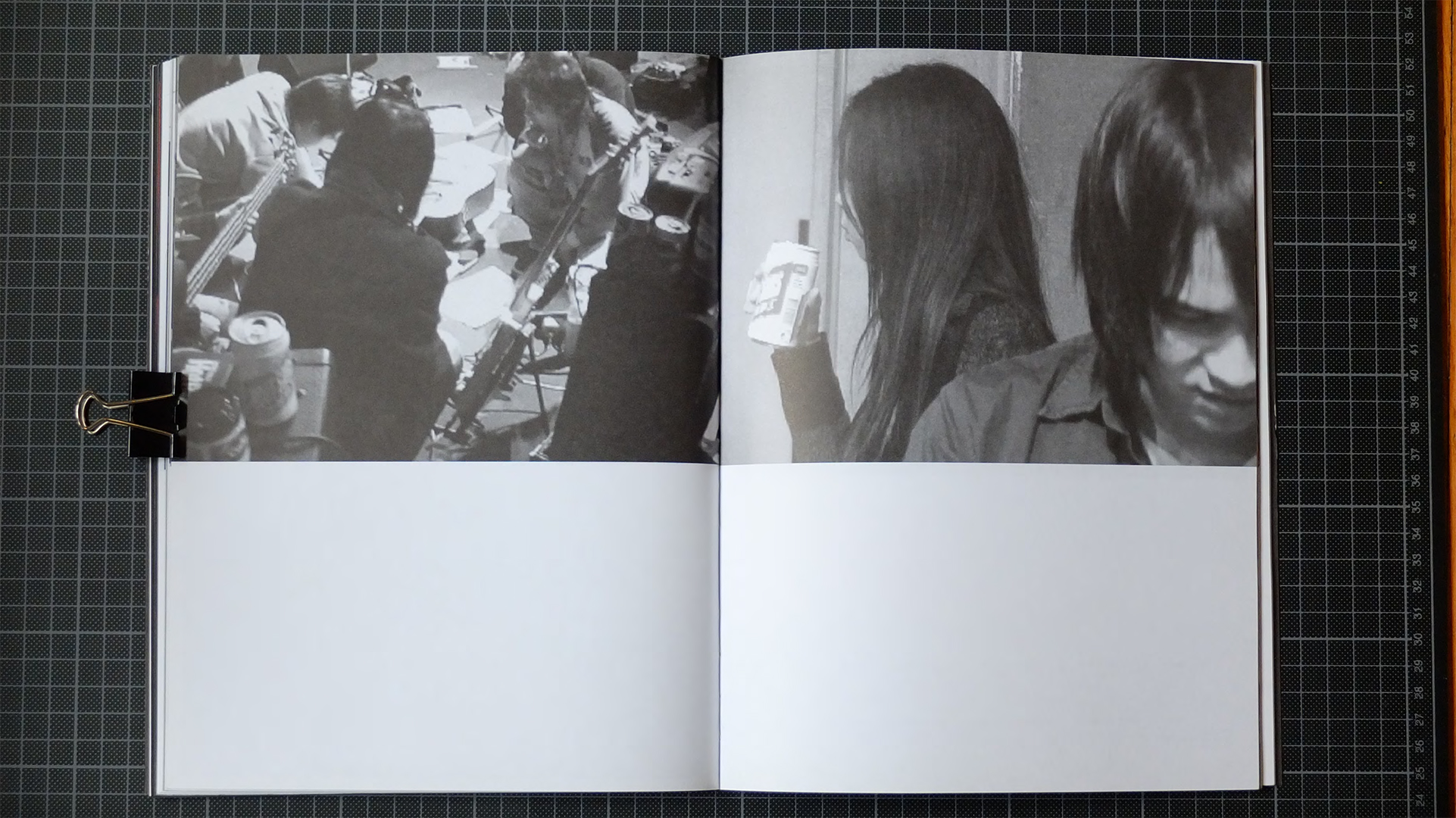

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

24’ 29’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

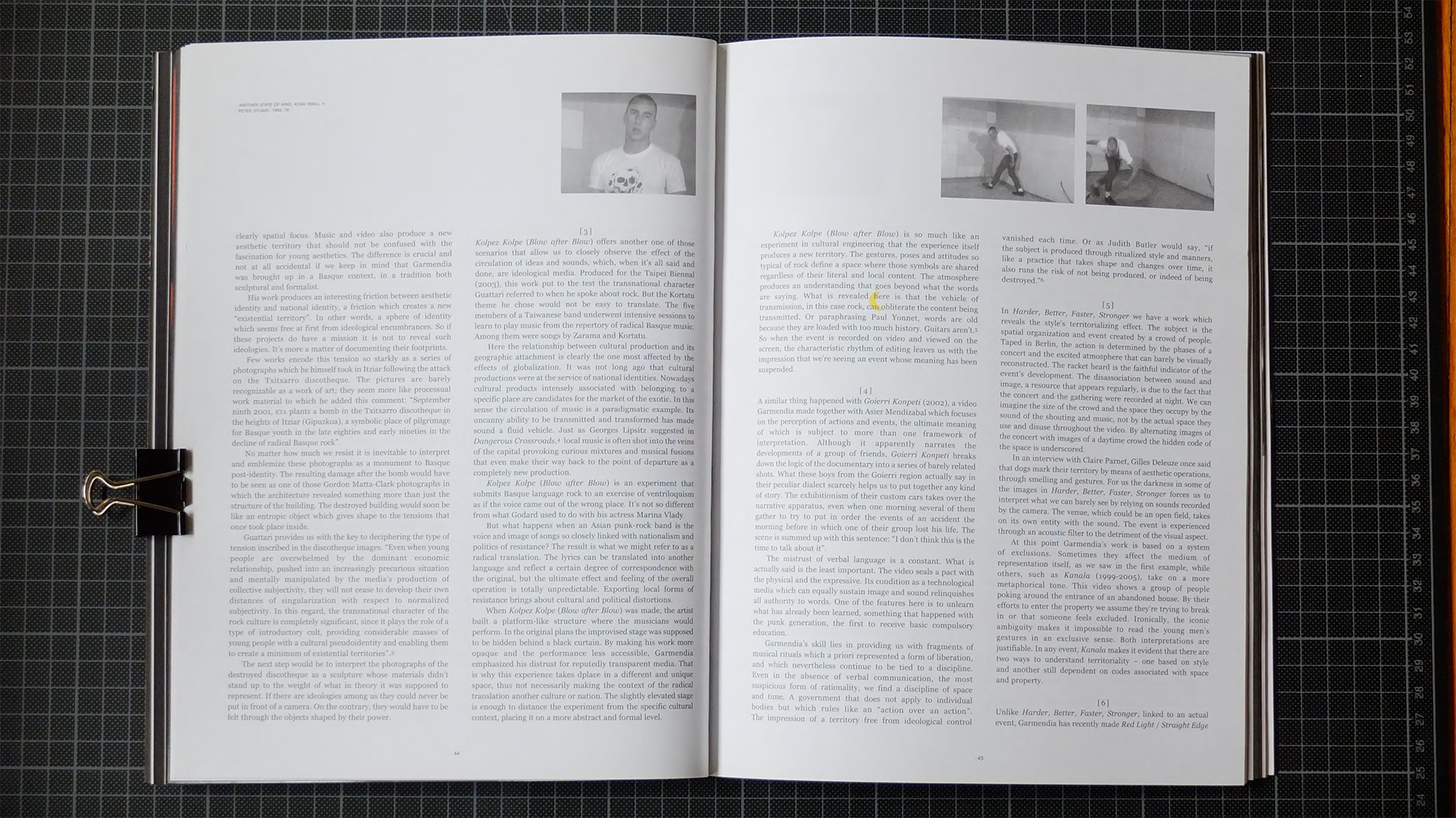

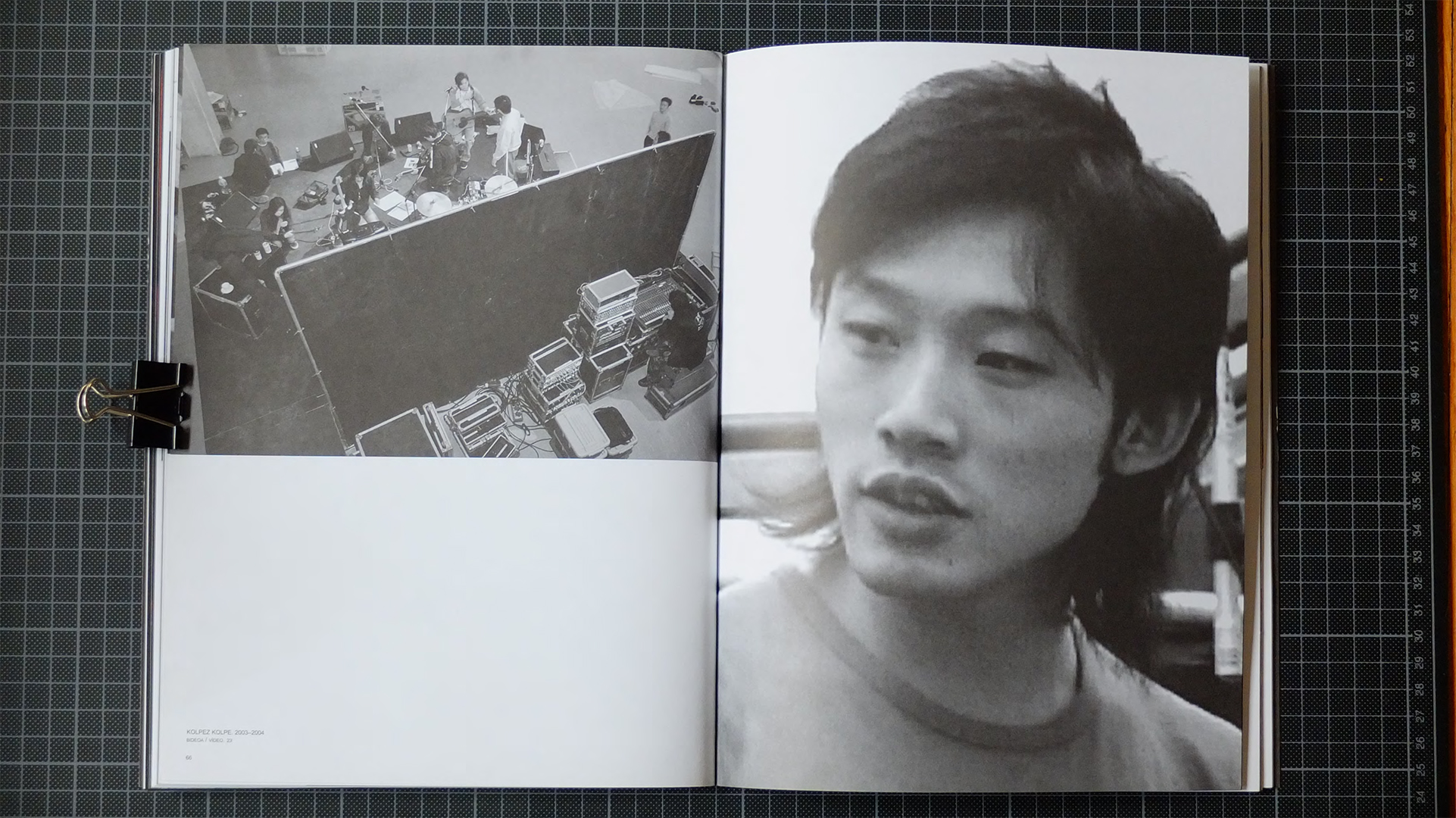

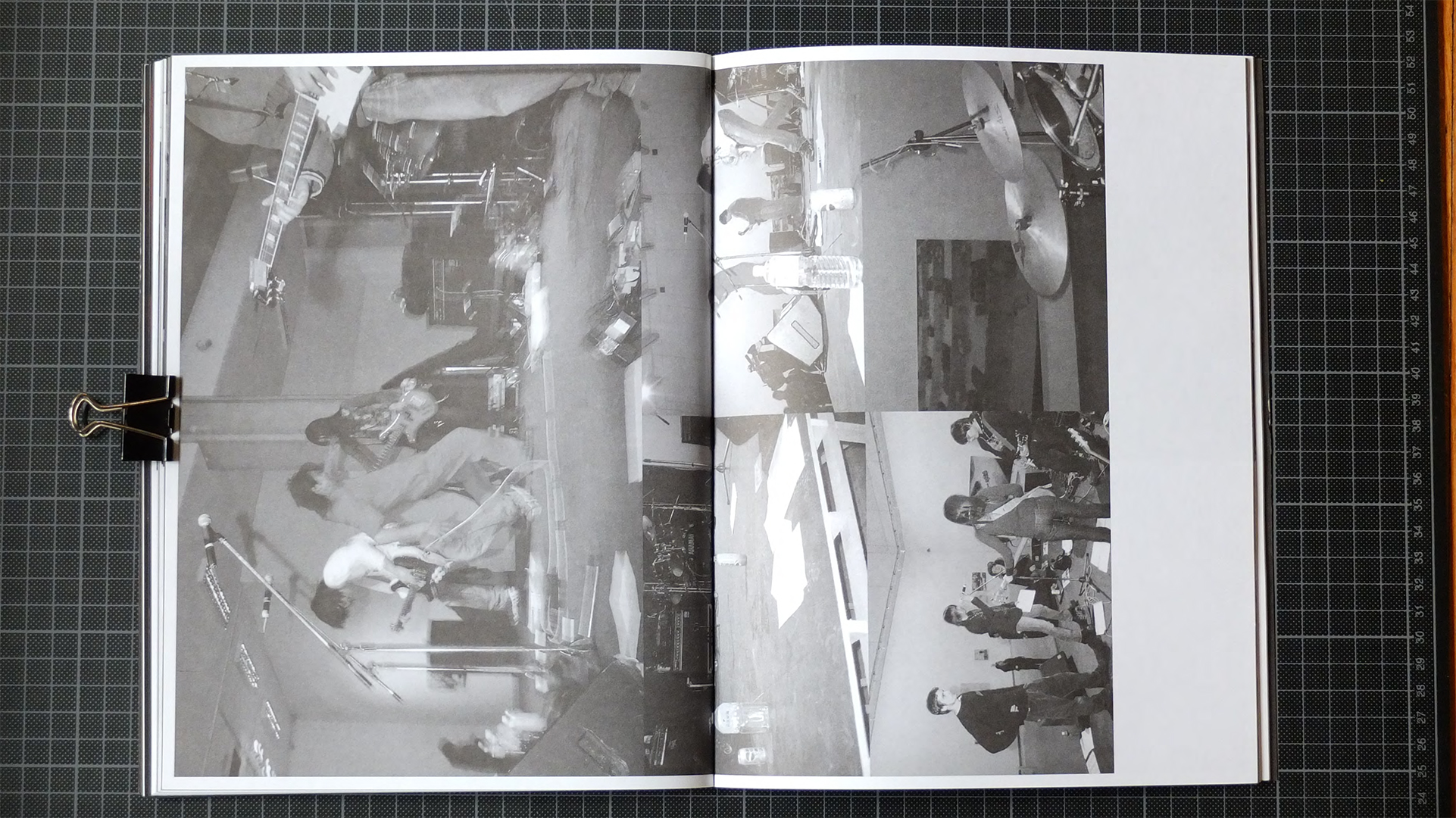

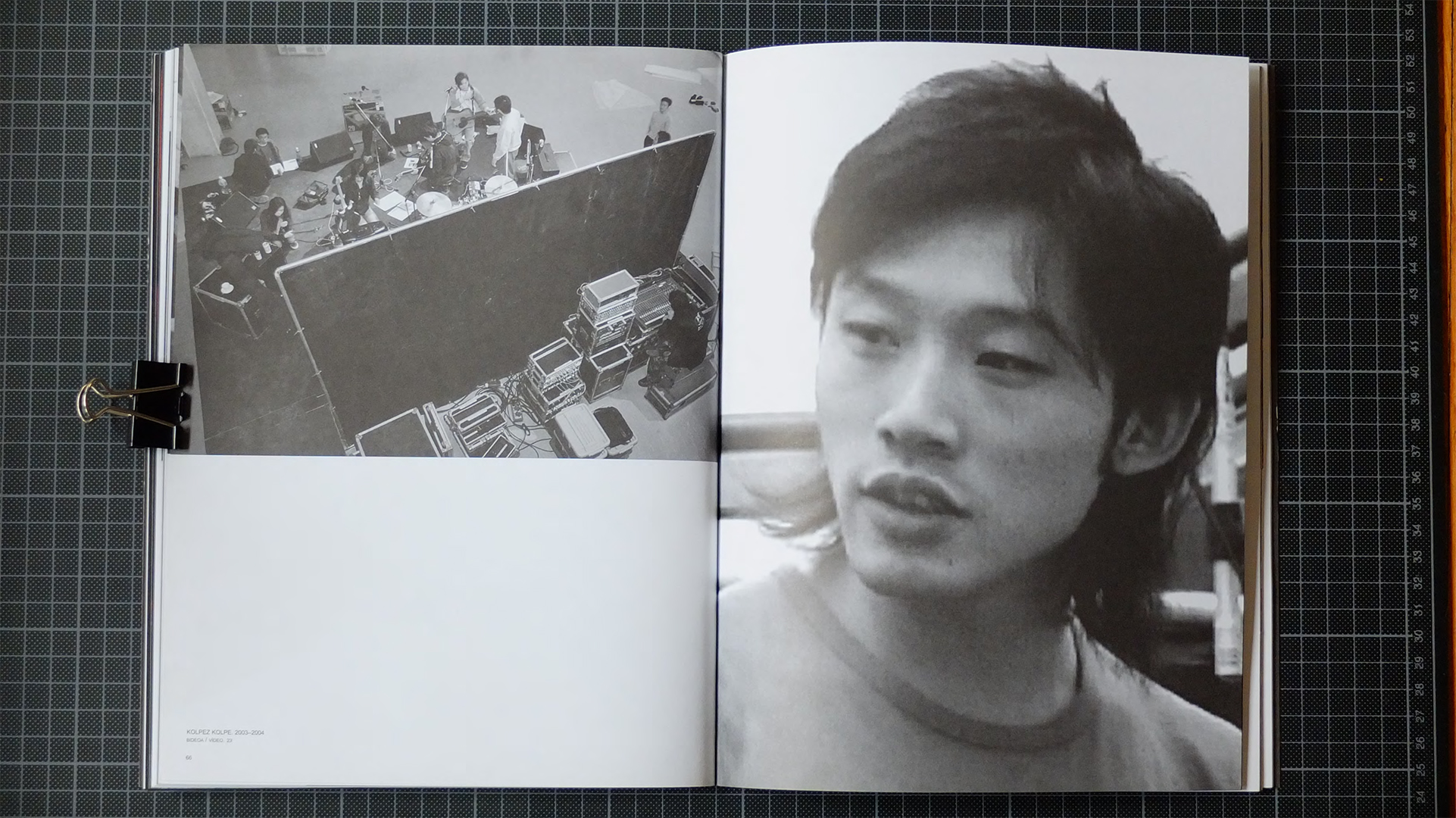

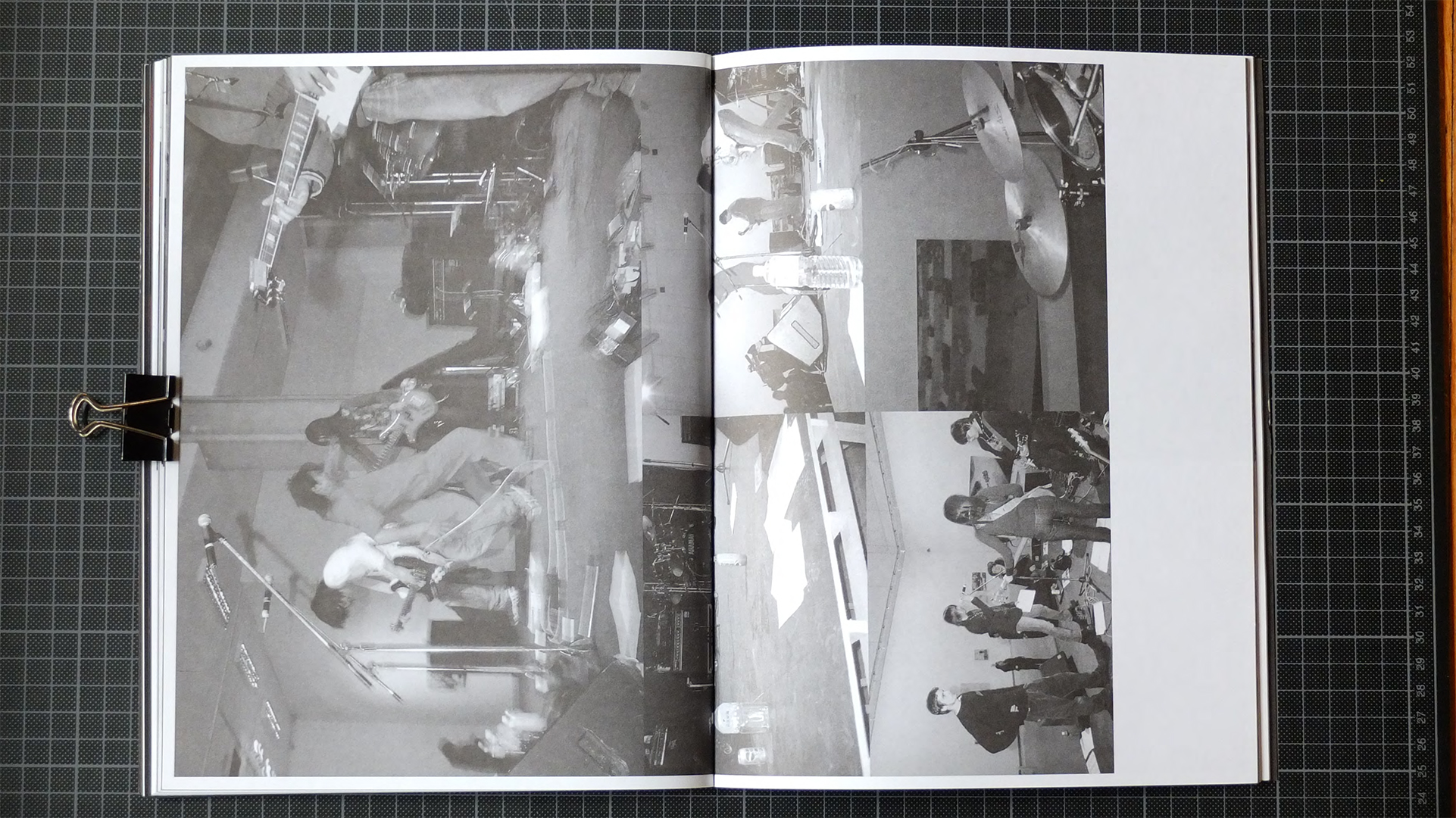

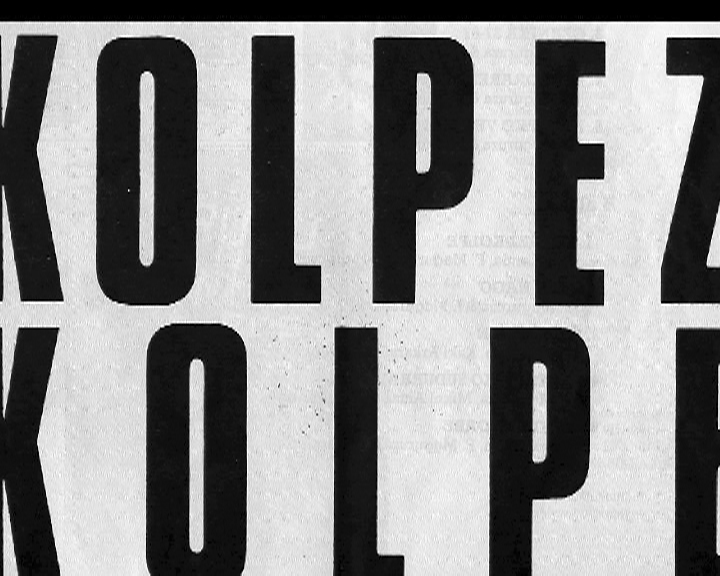

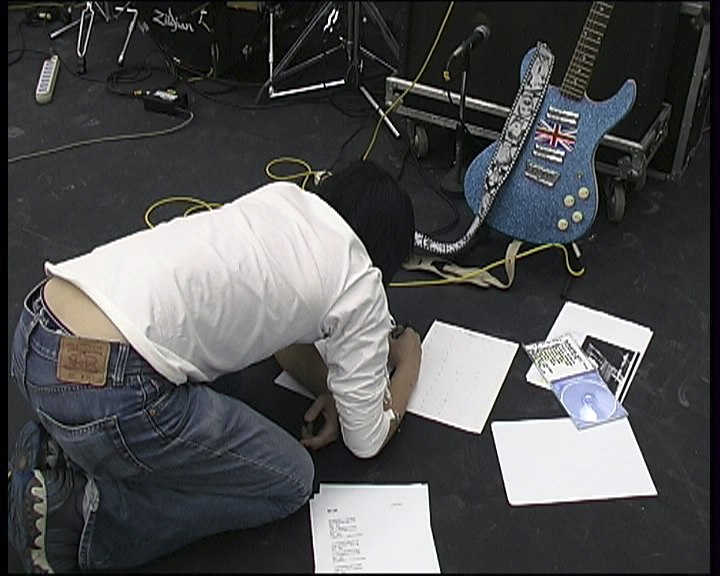

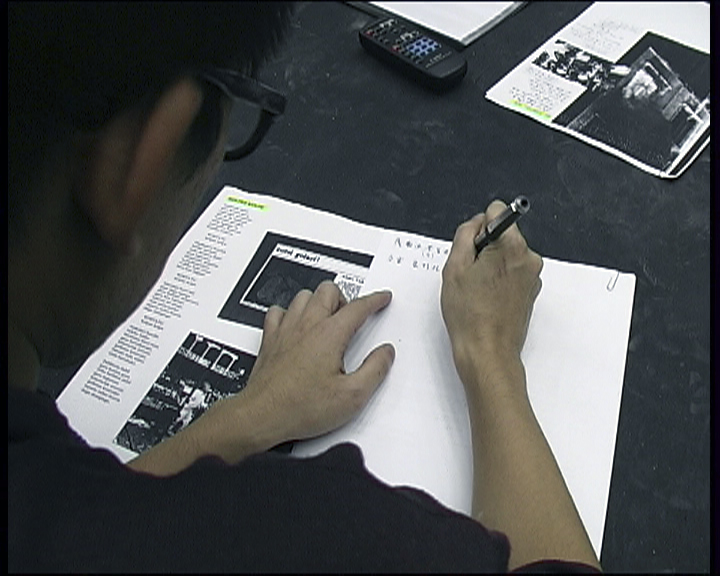

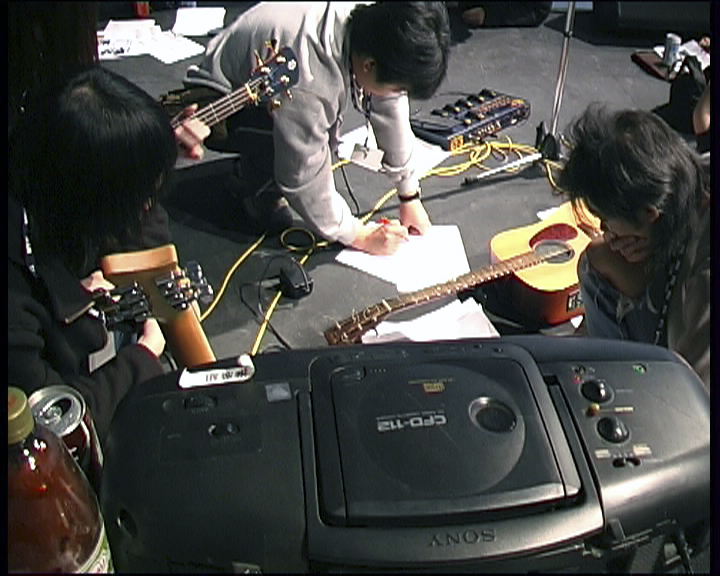

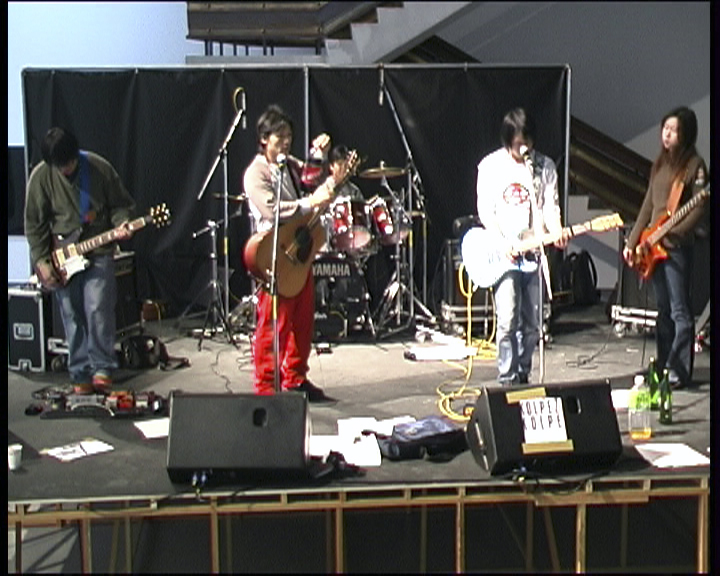

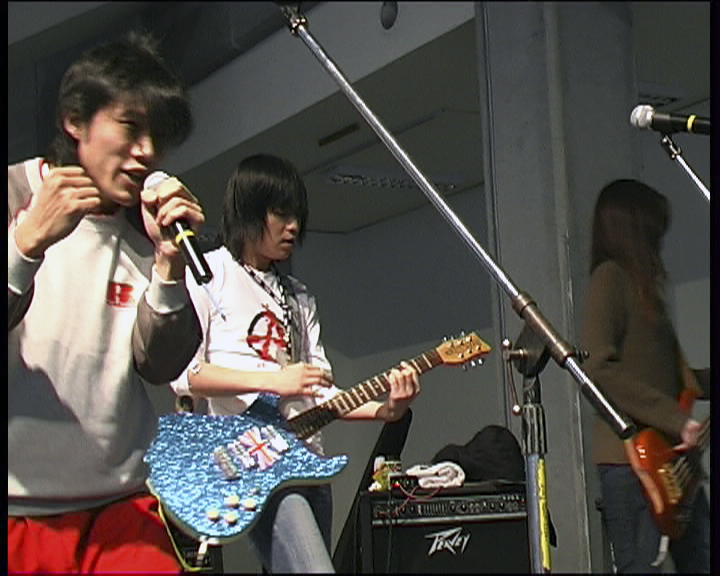

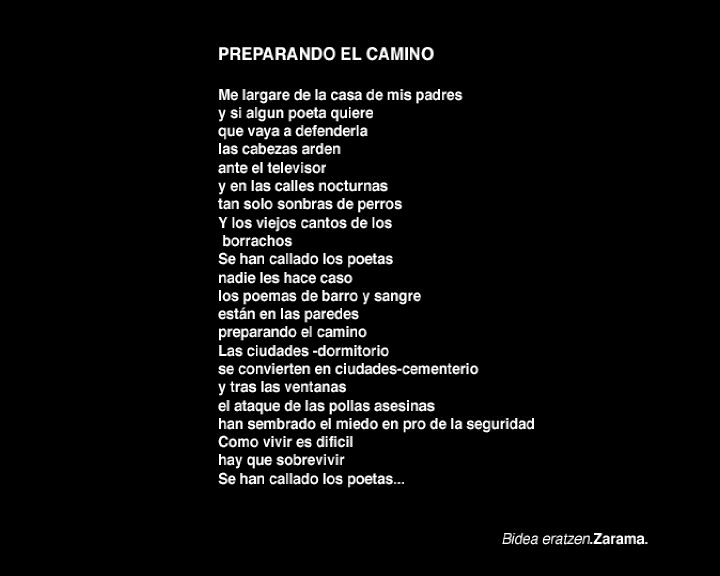

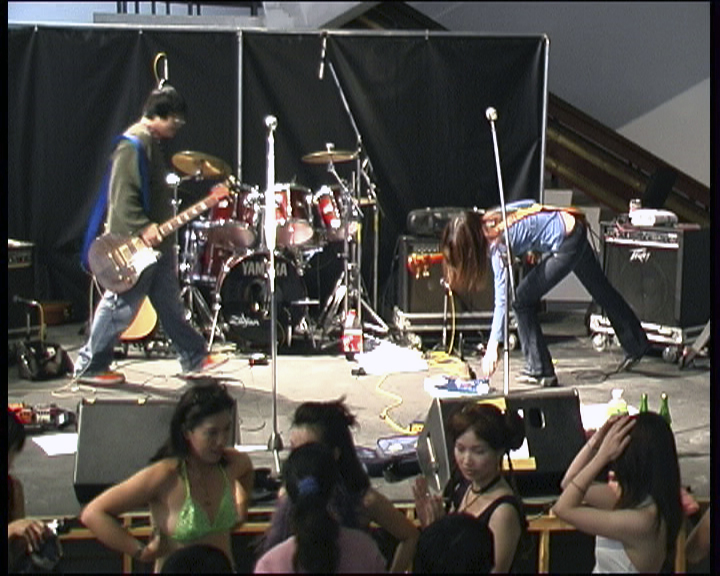

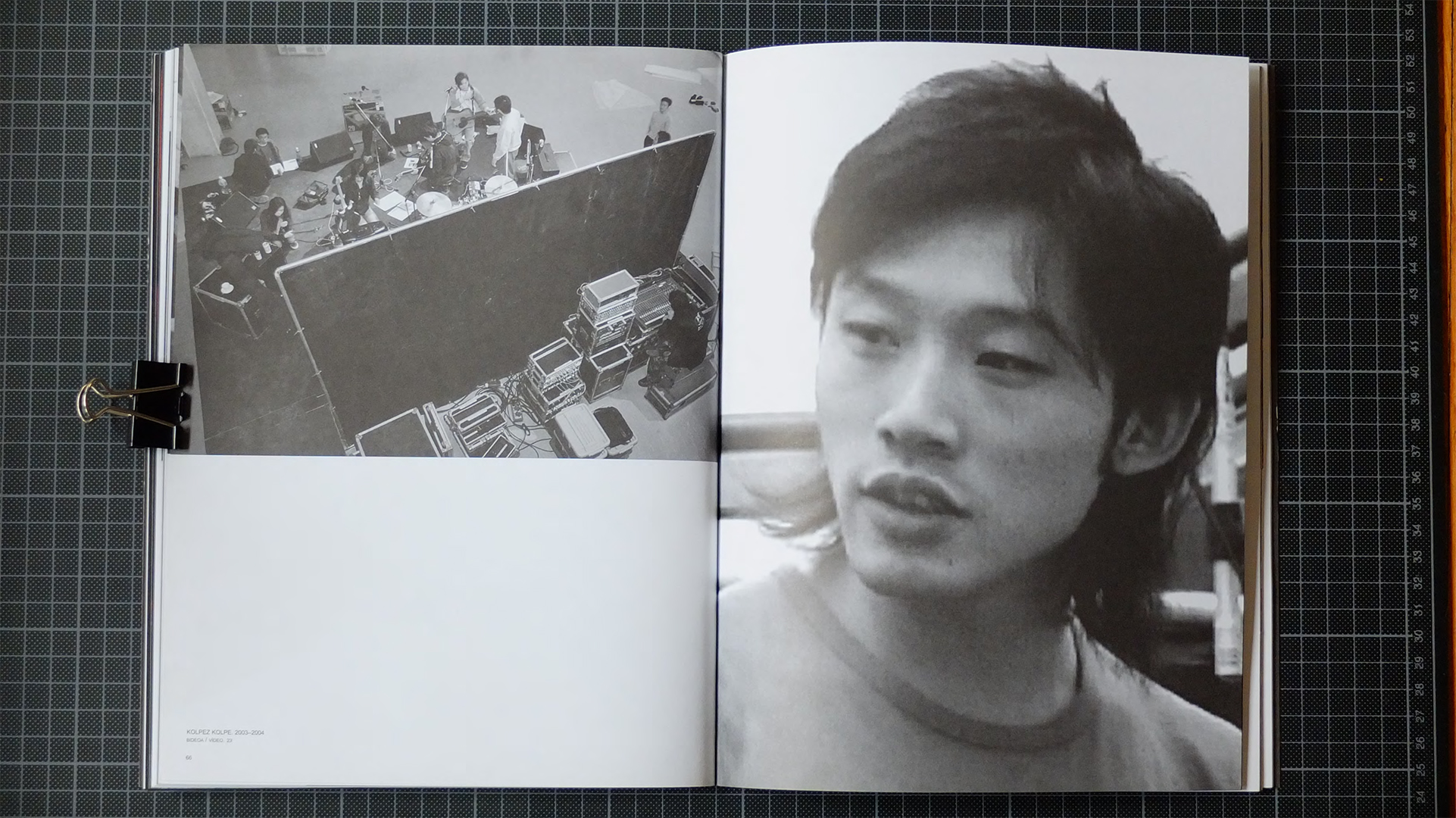

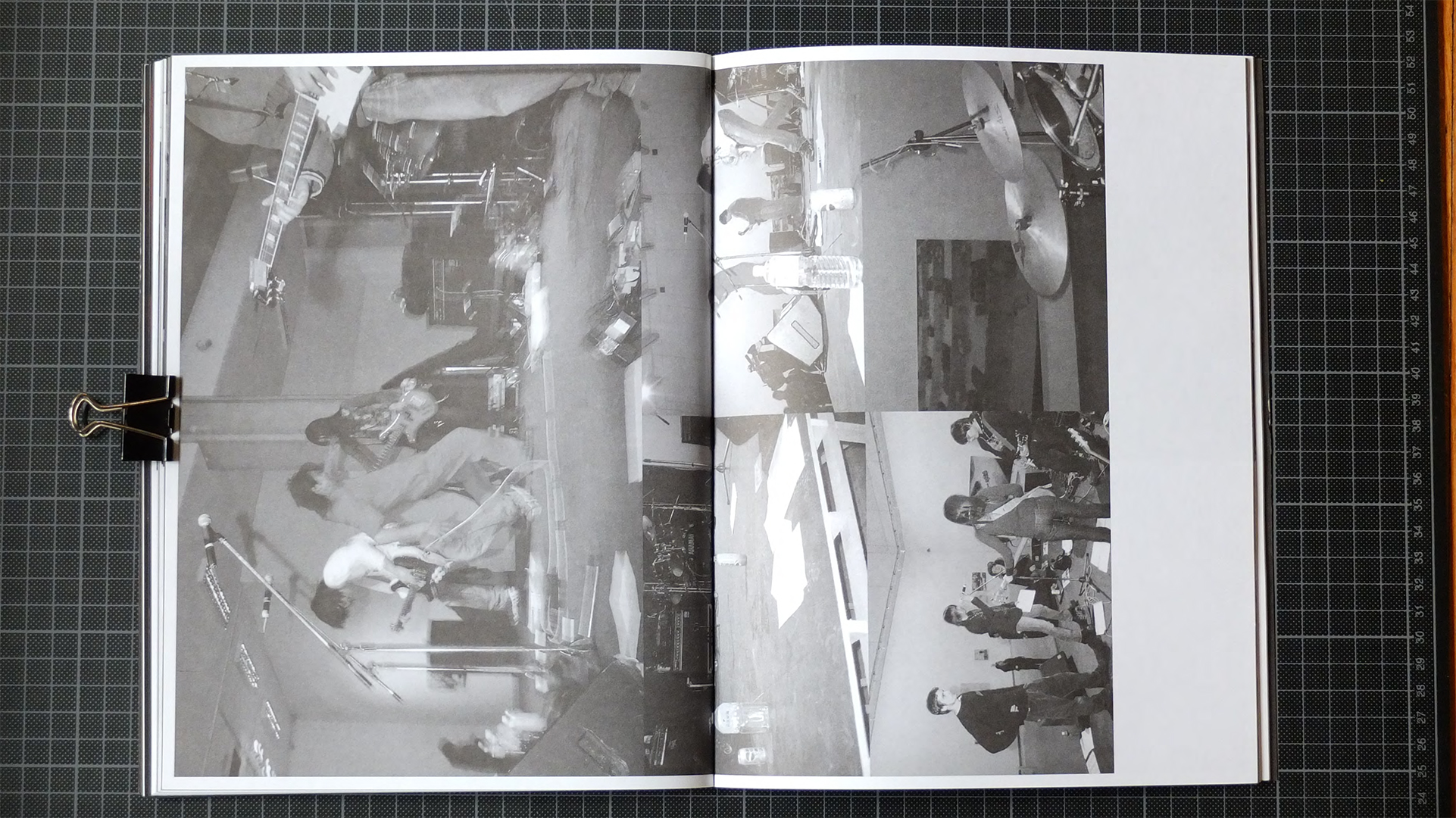

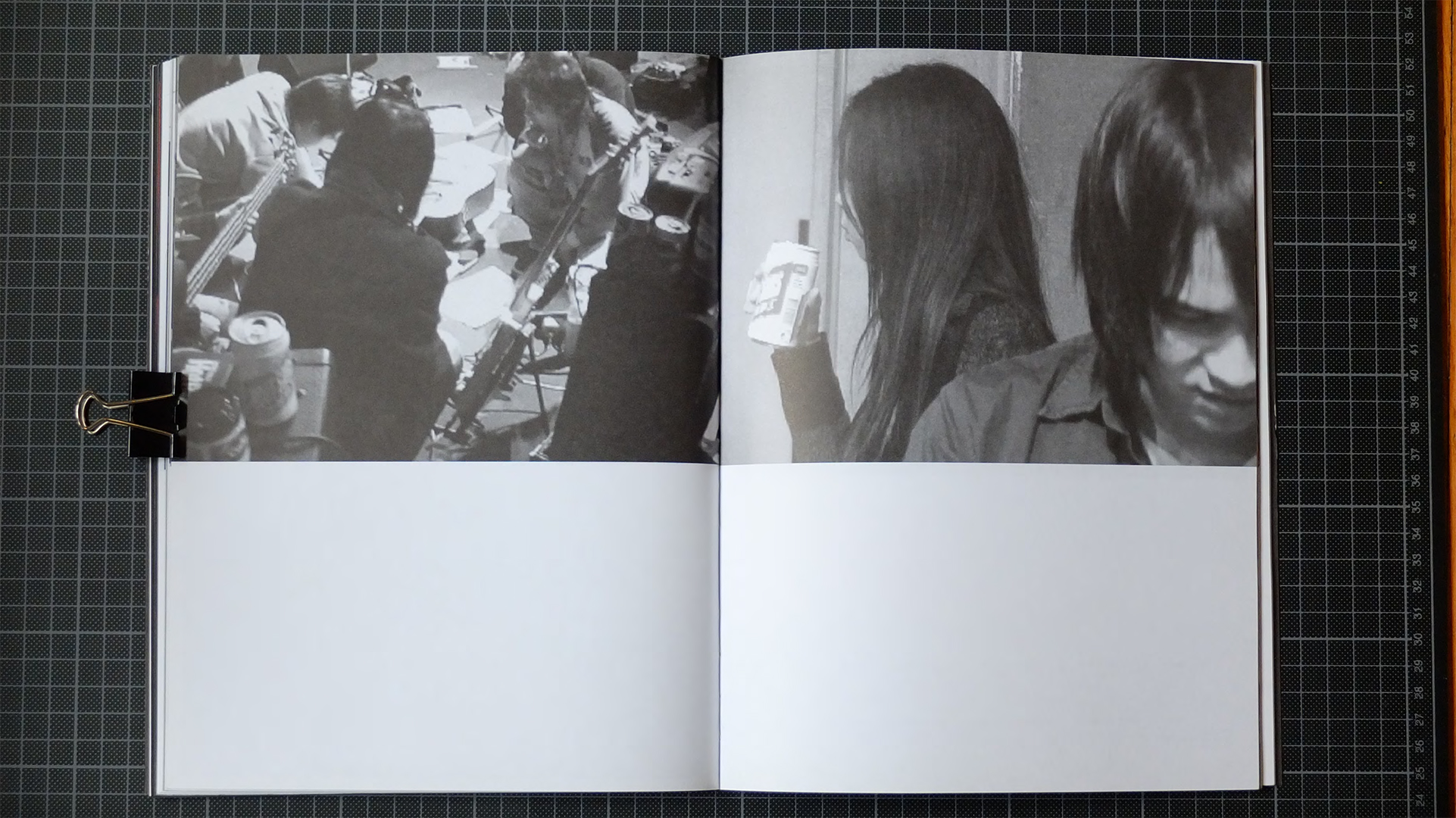

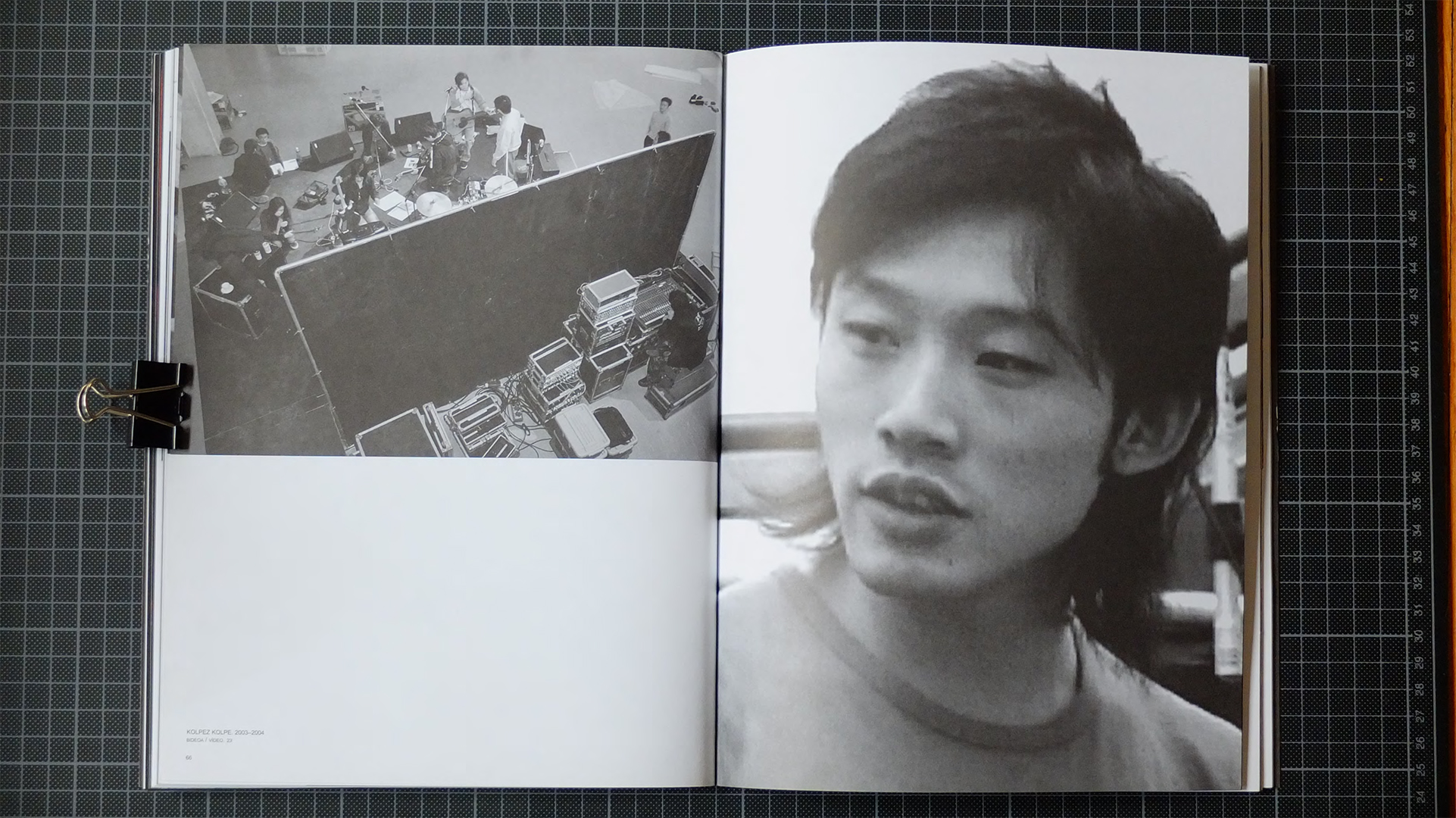

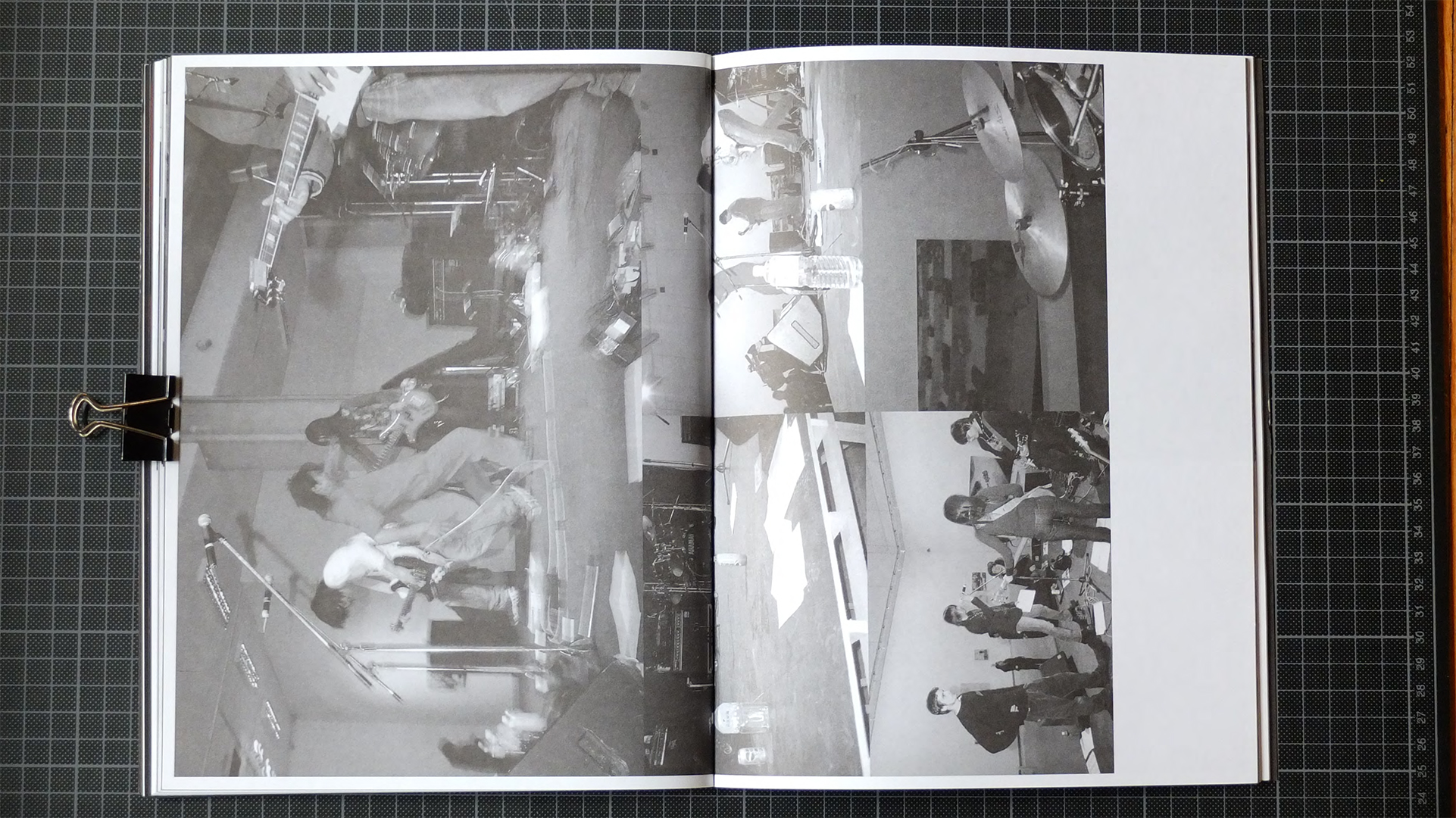

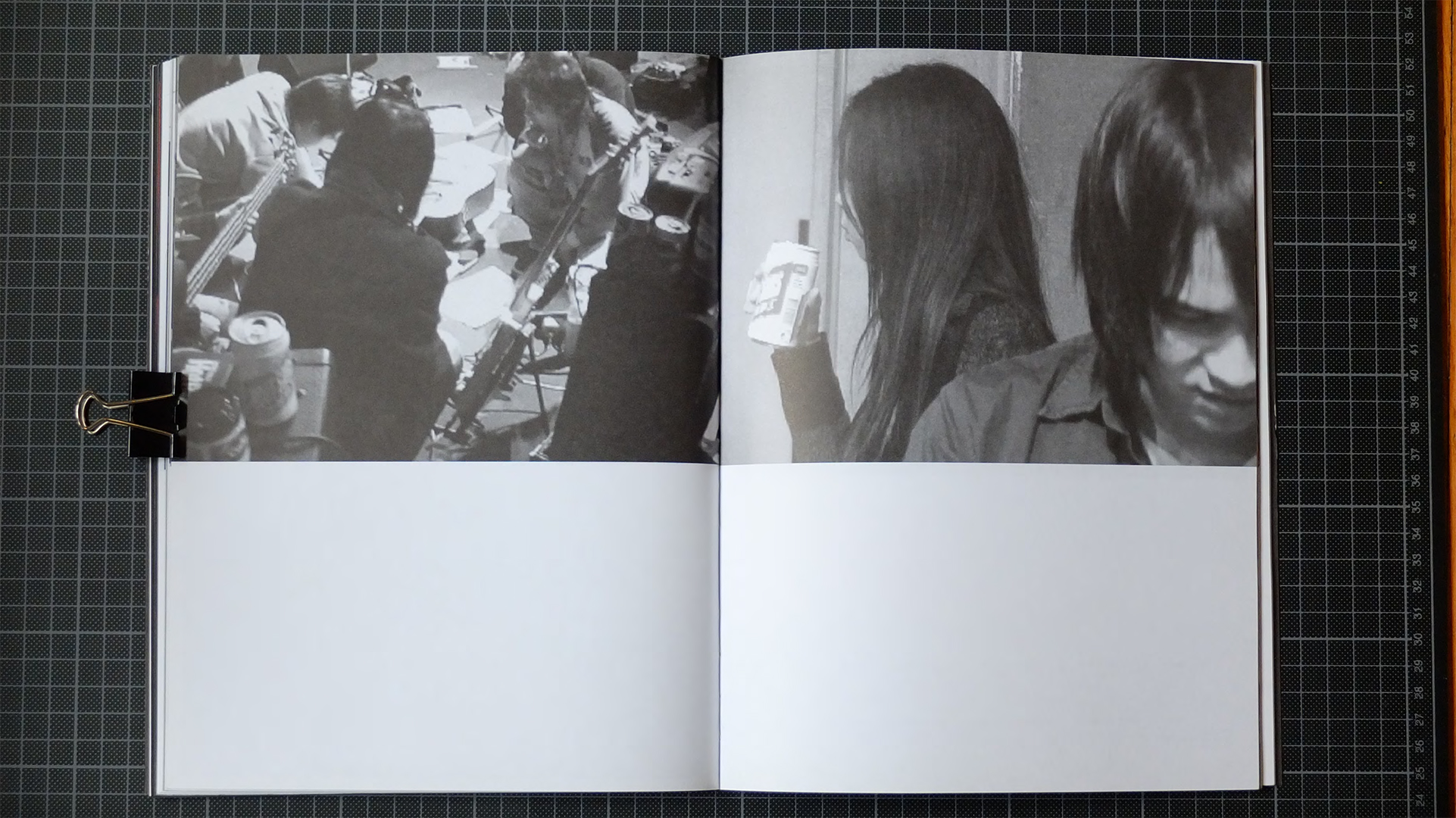

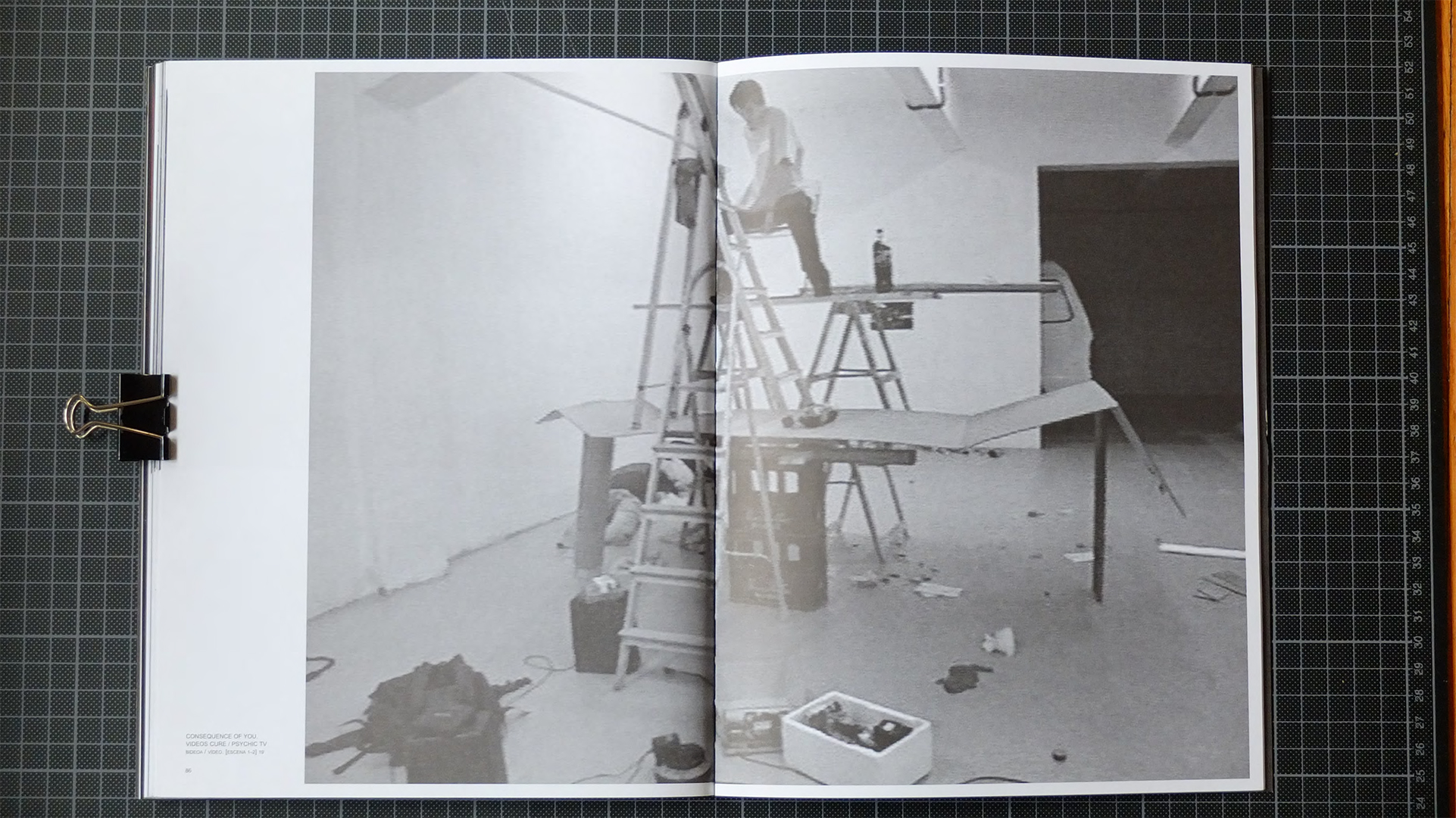

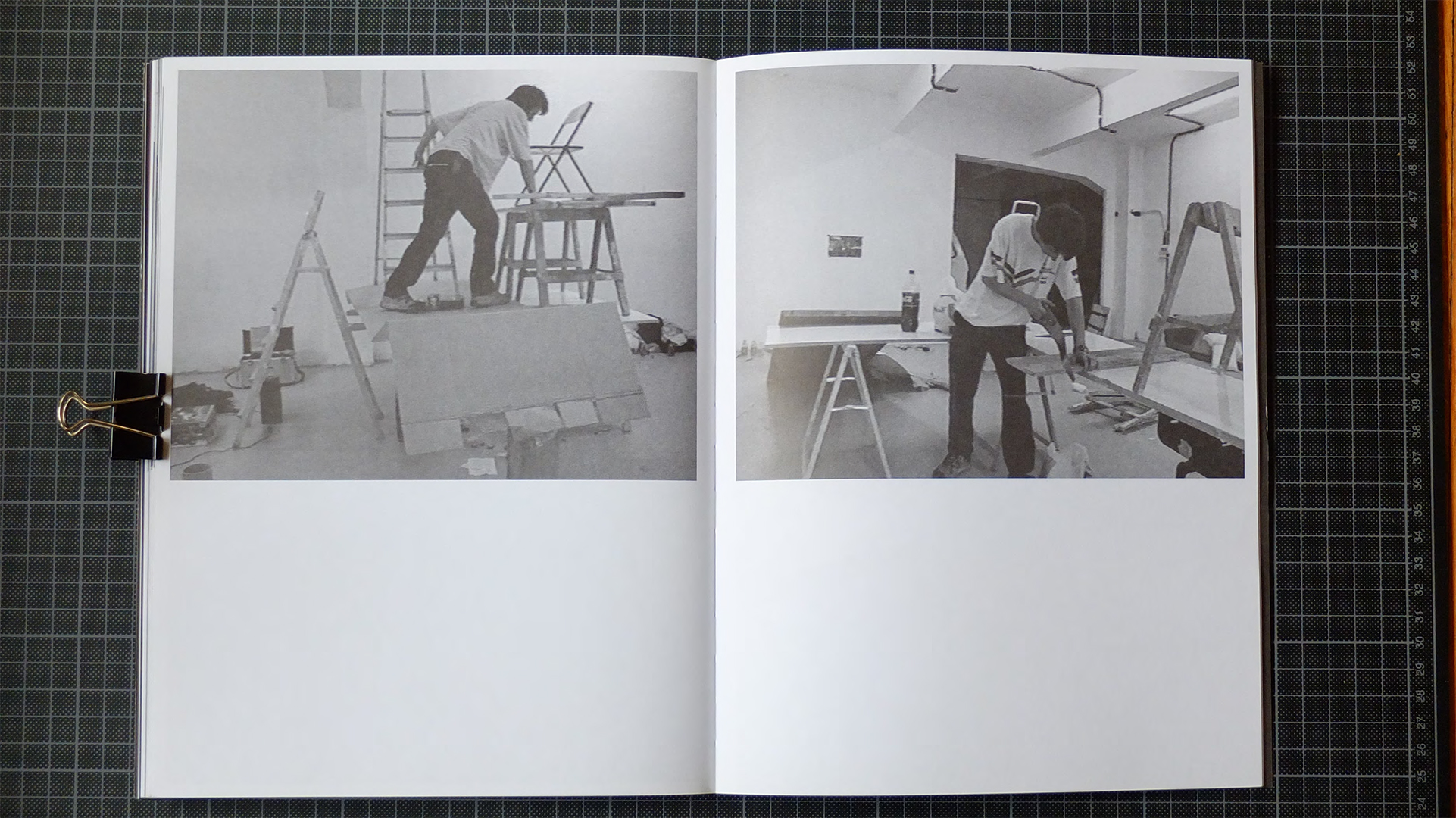

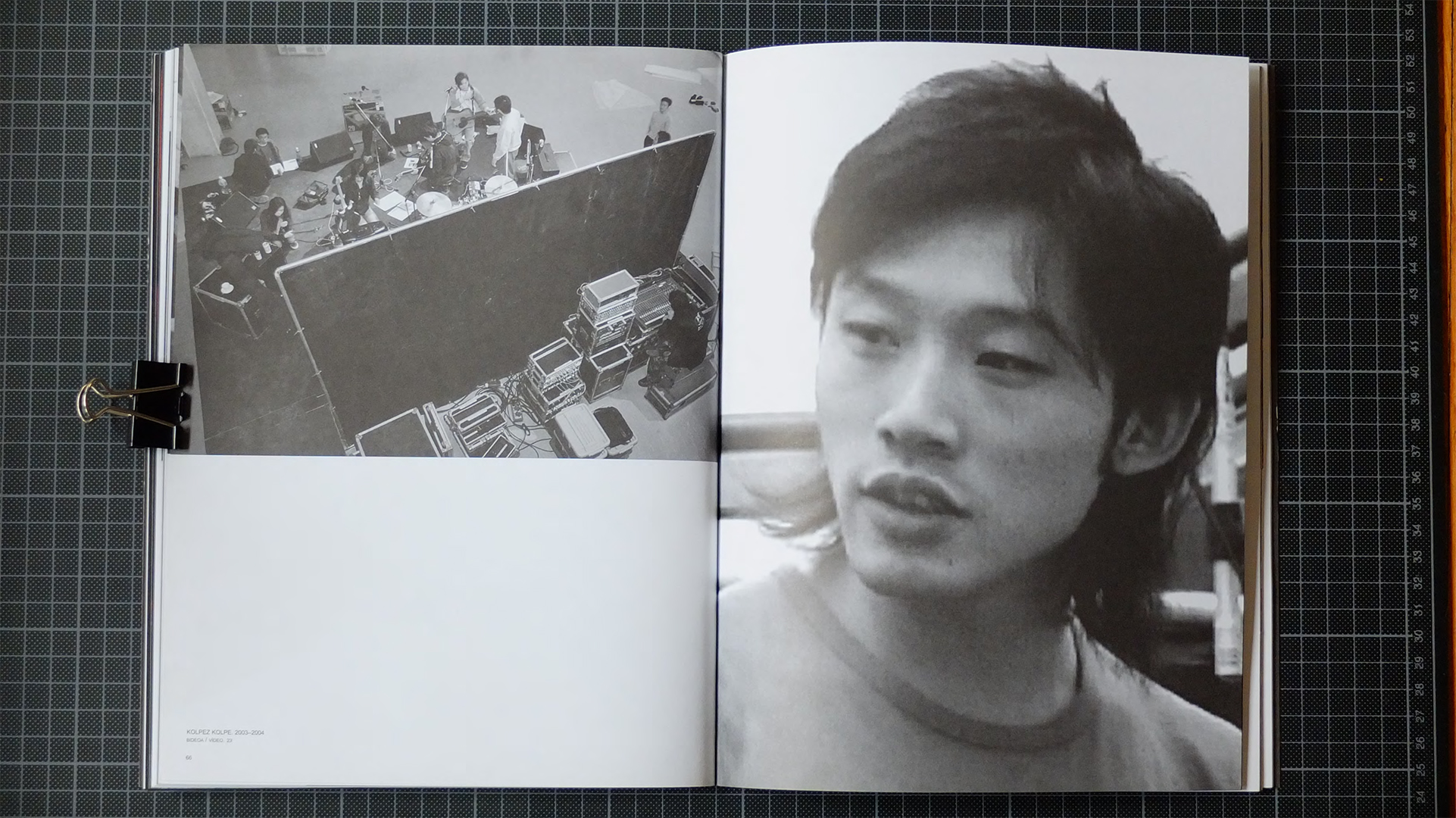

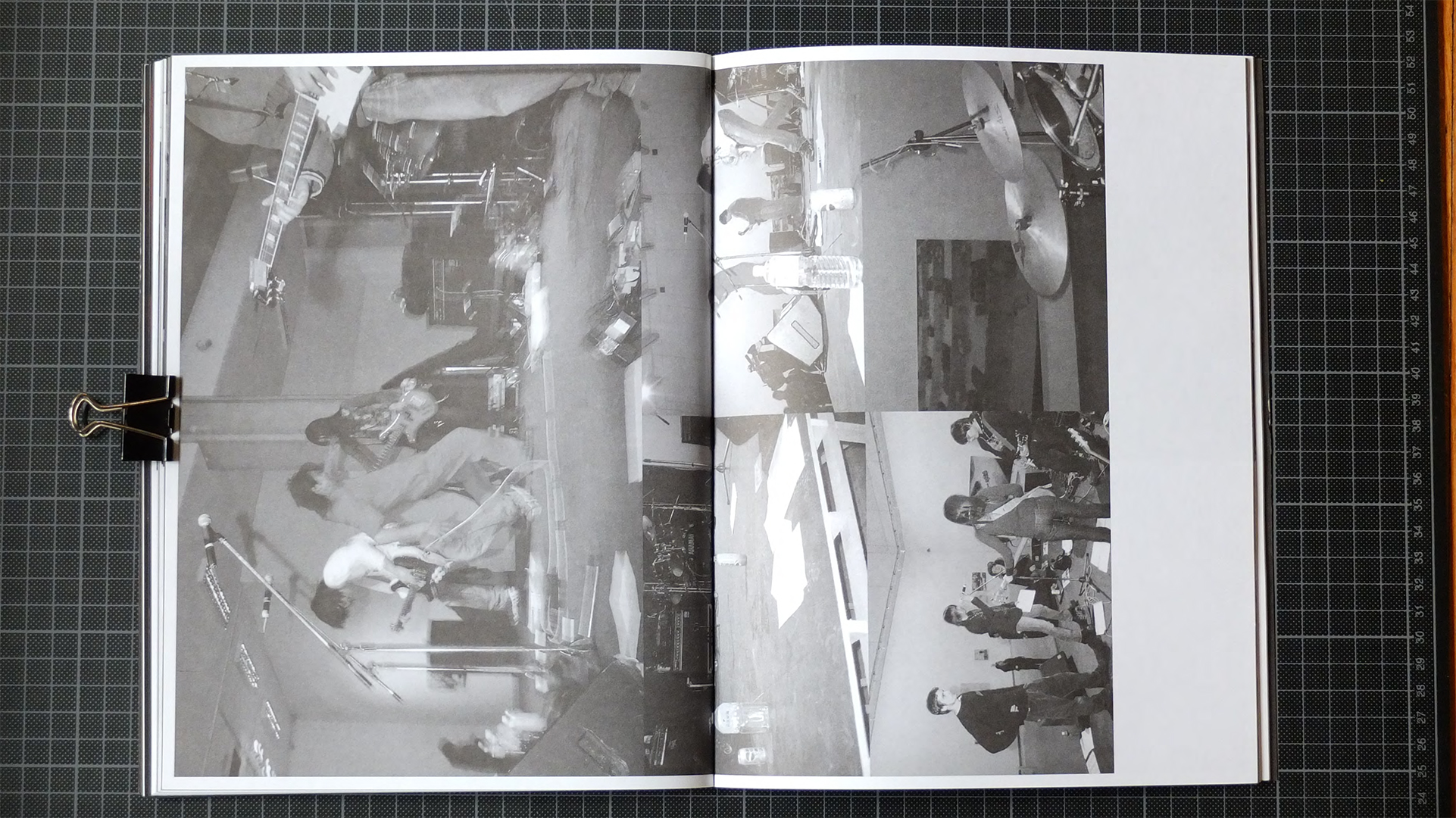

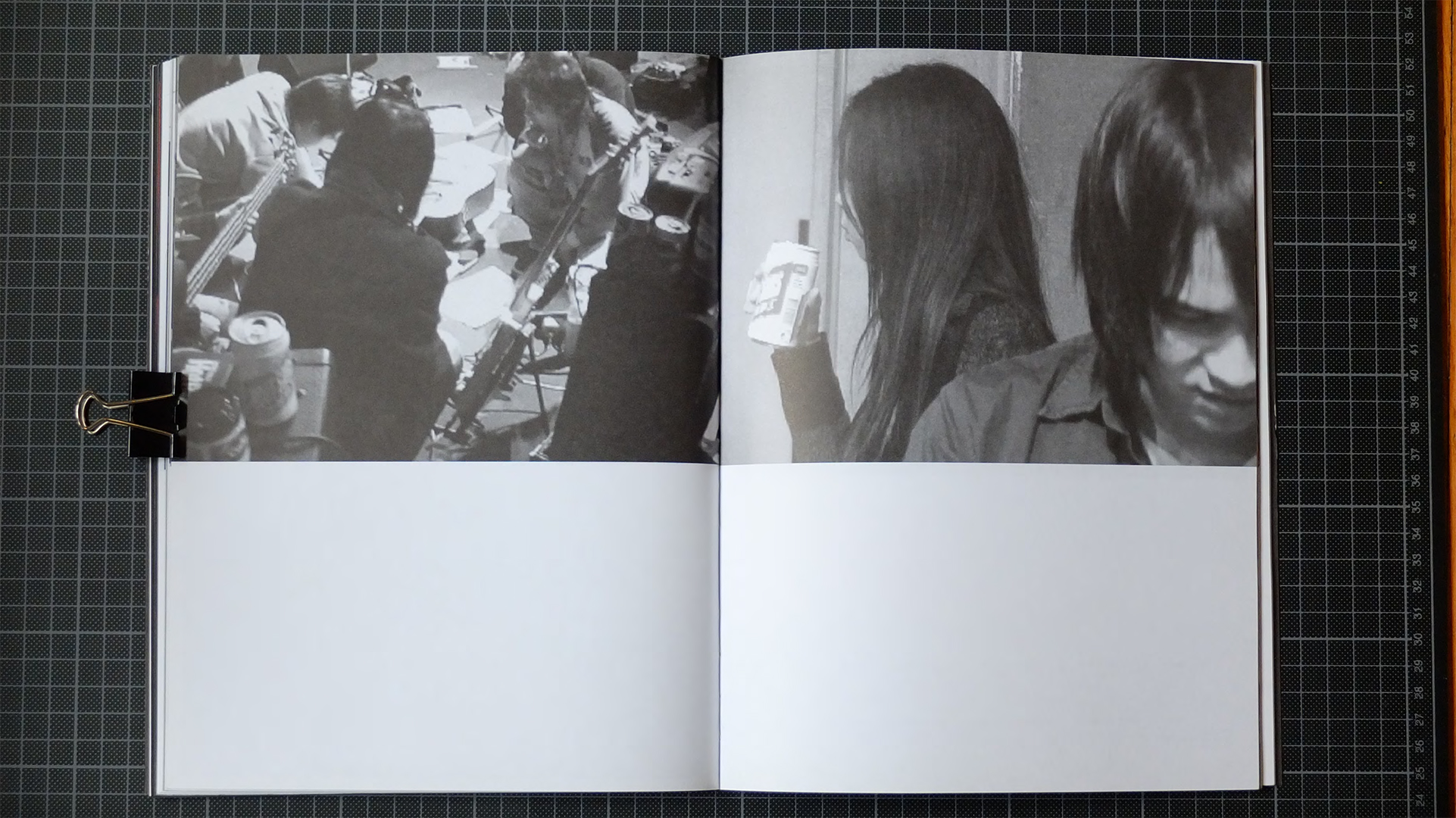

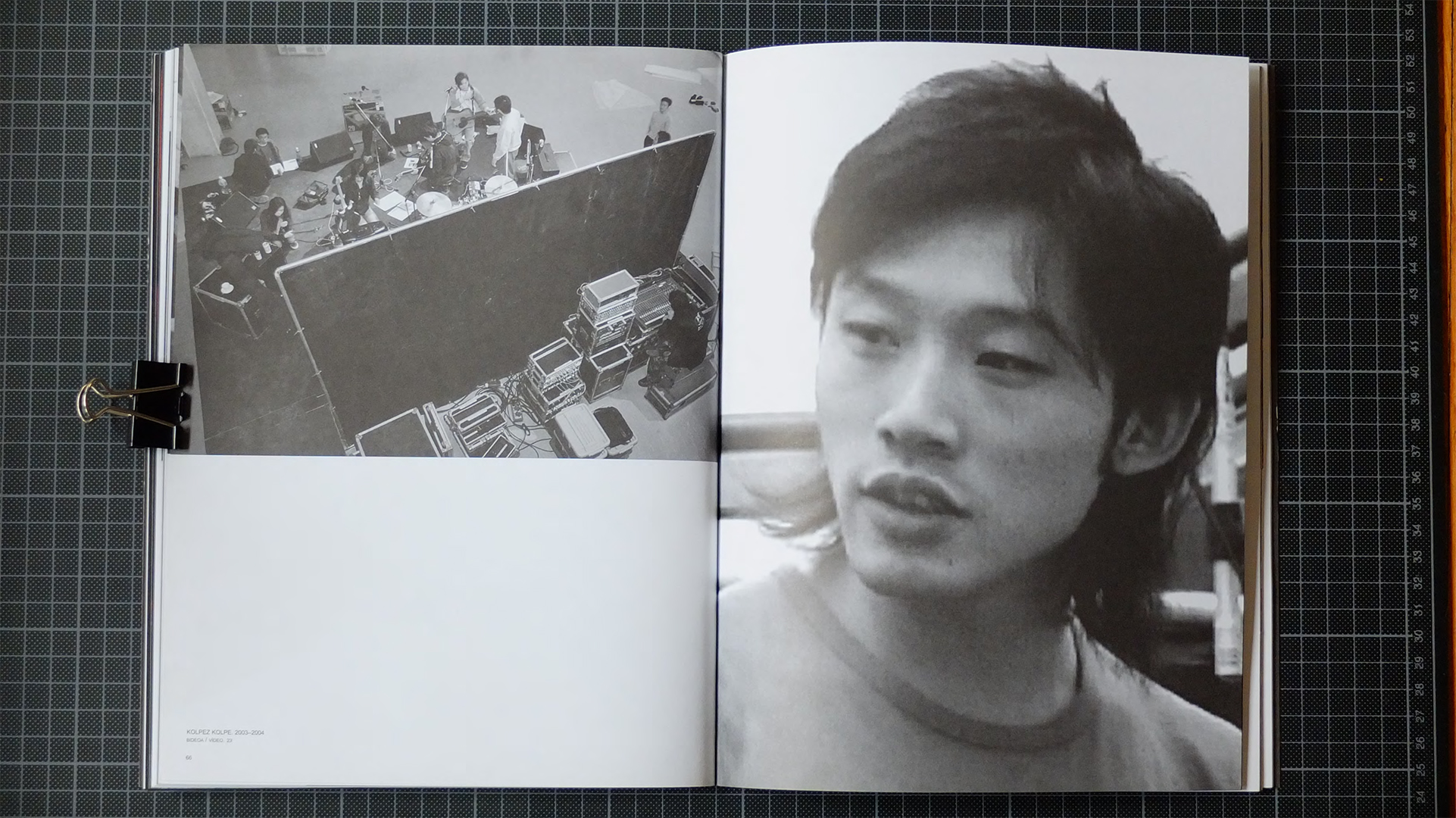

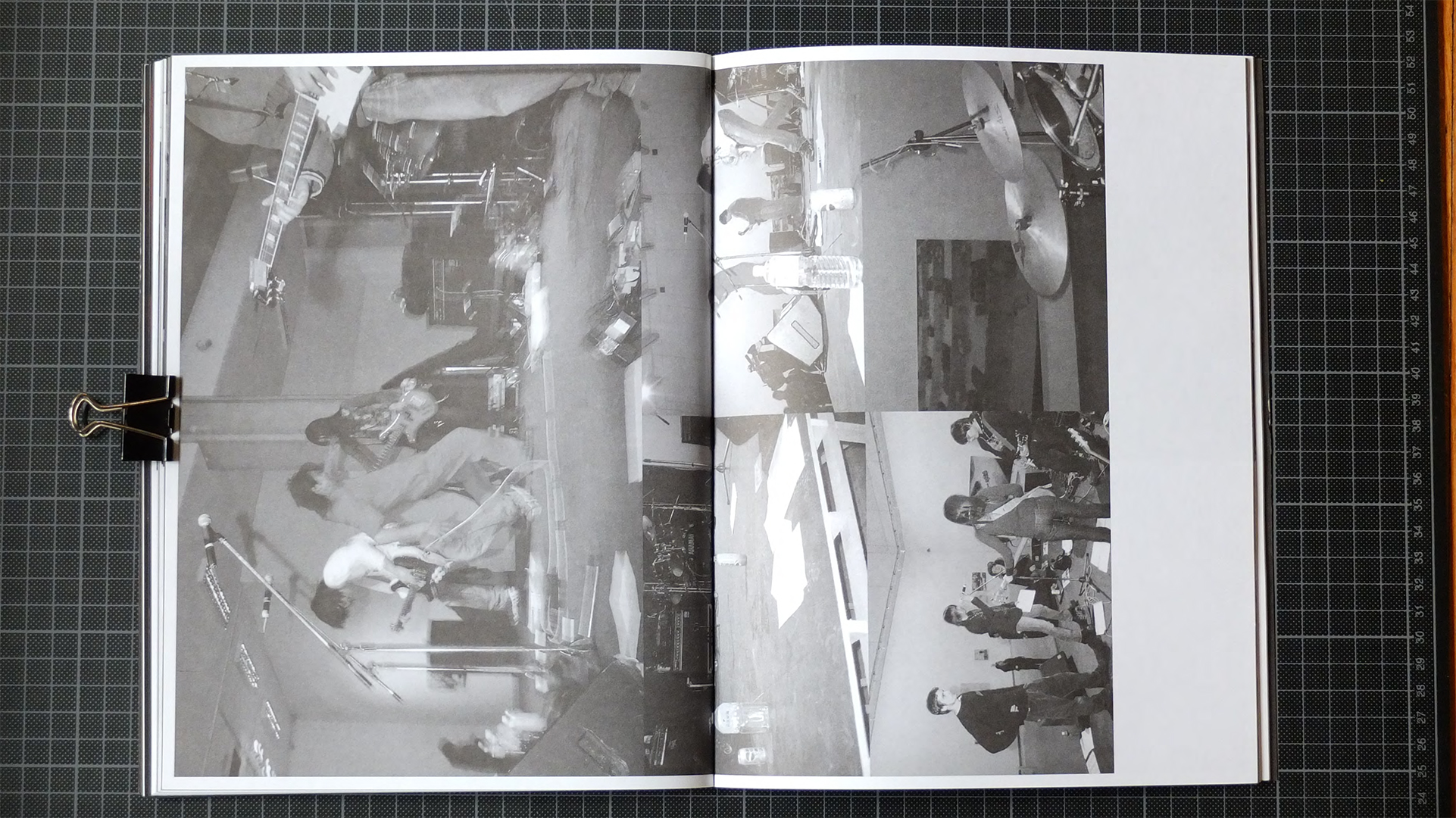

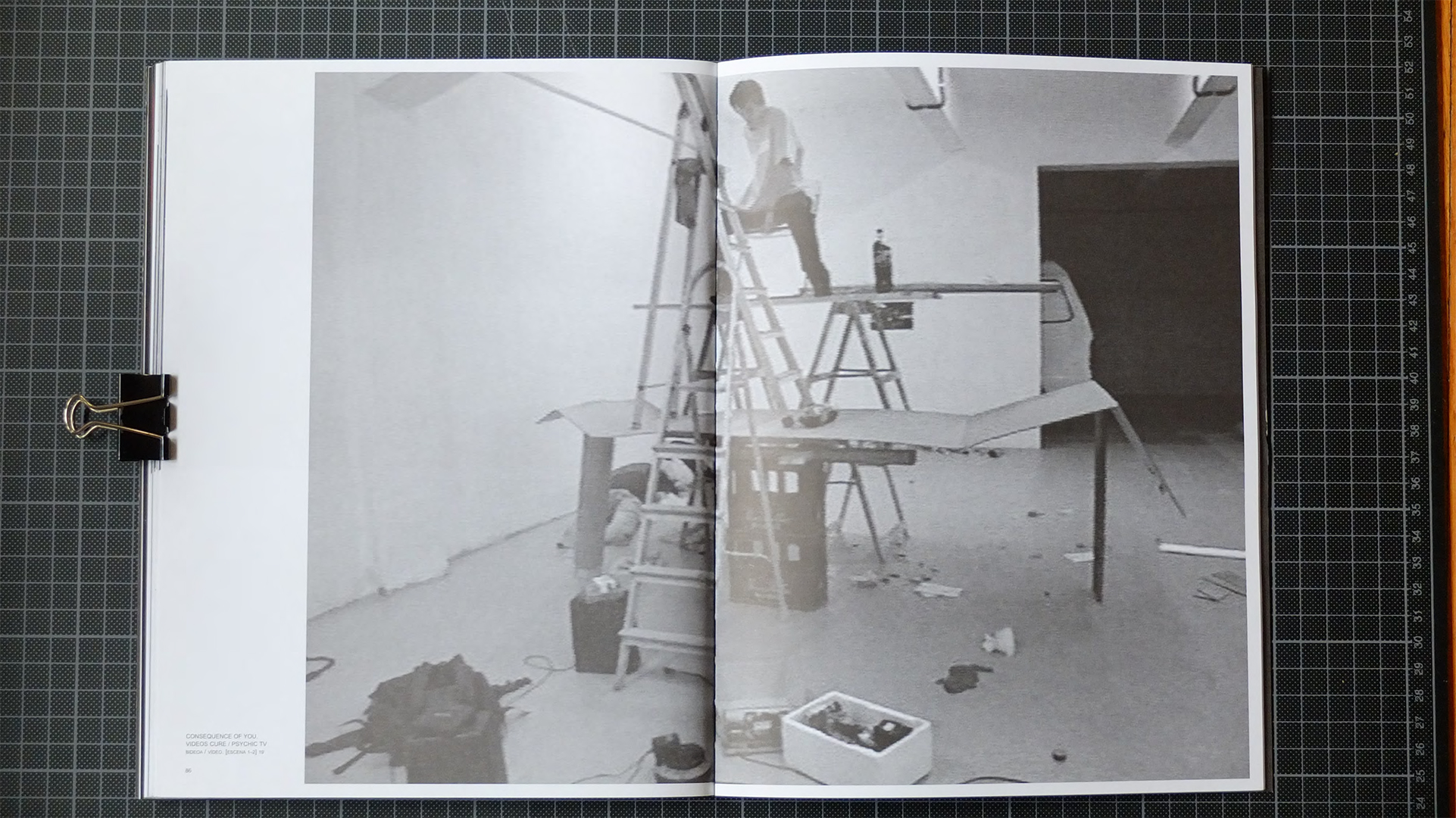

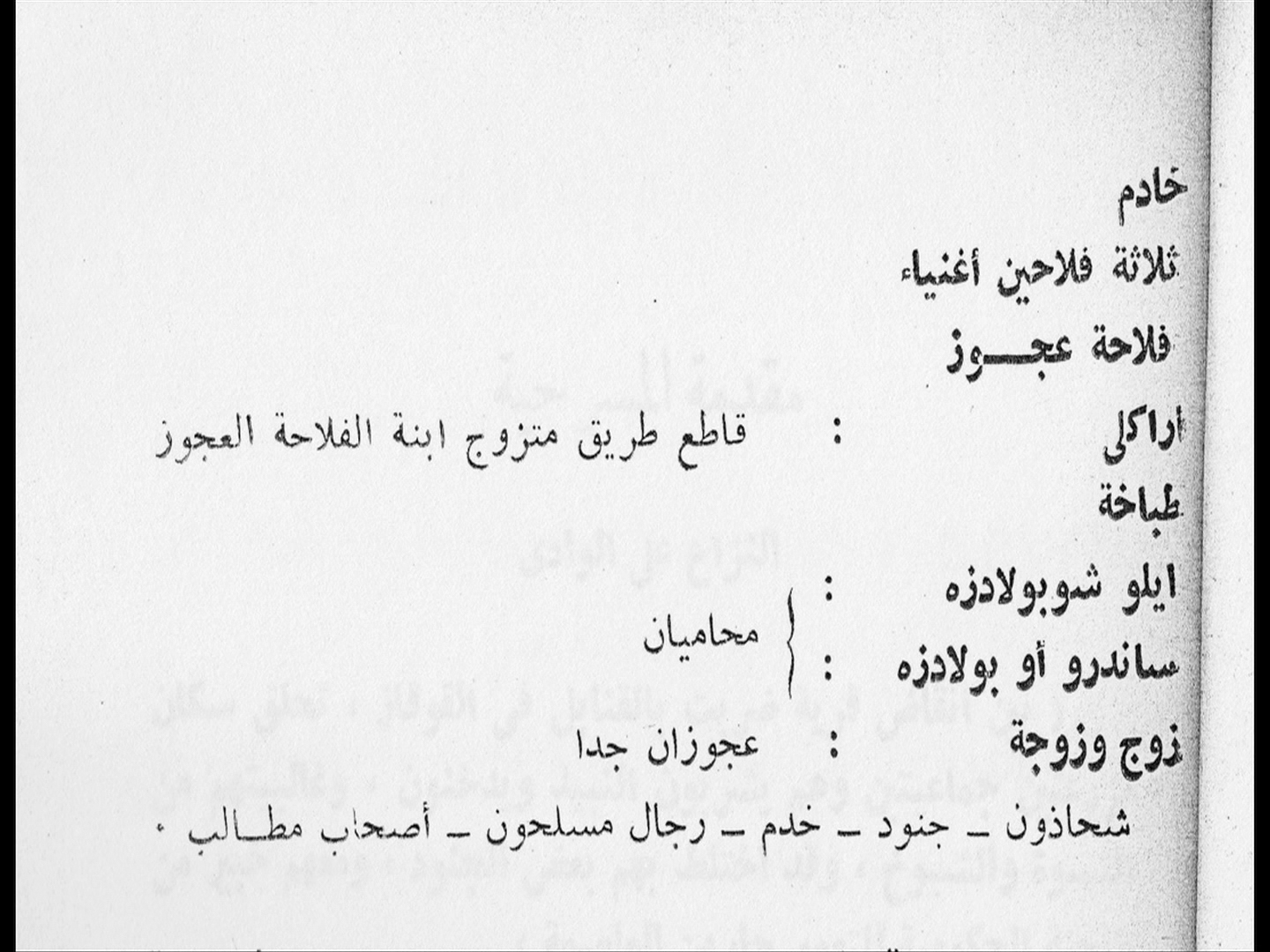

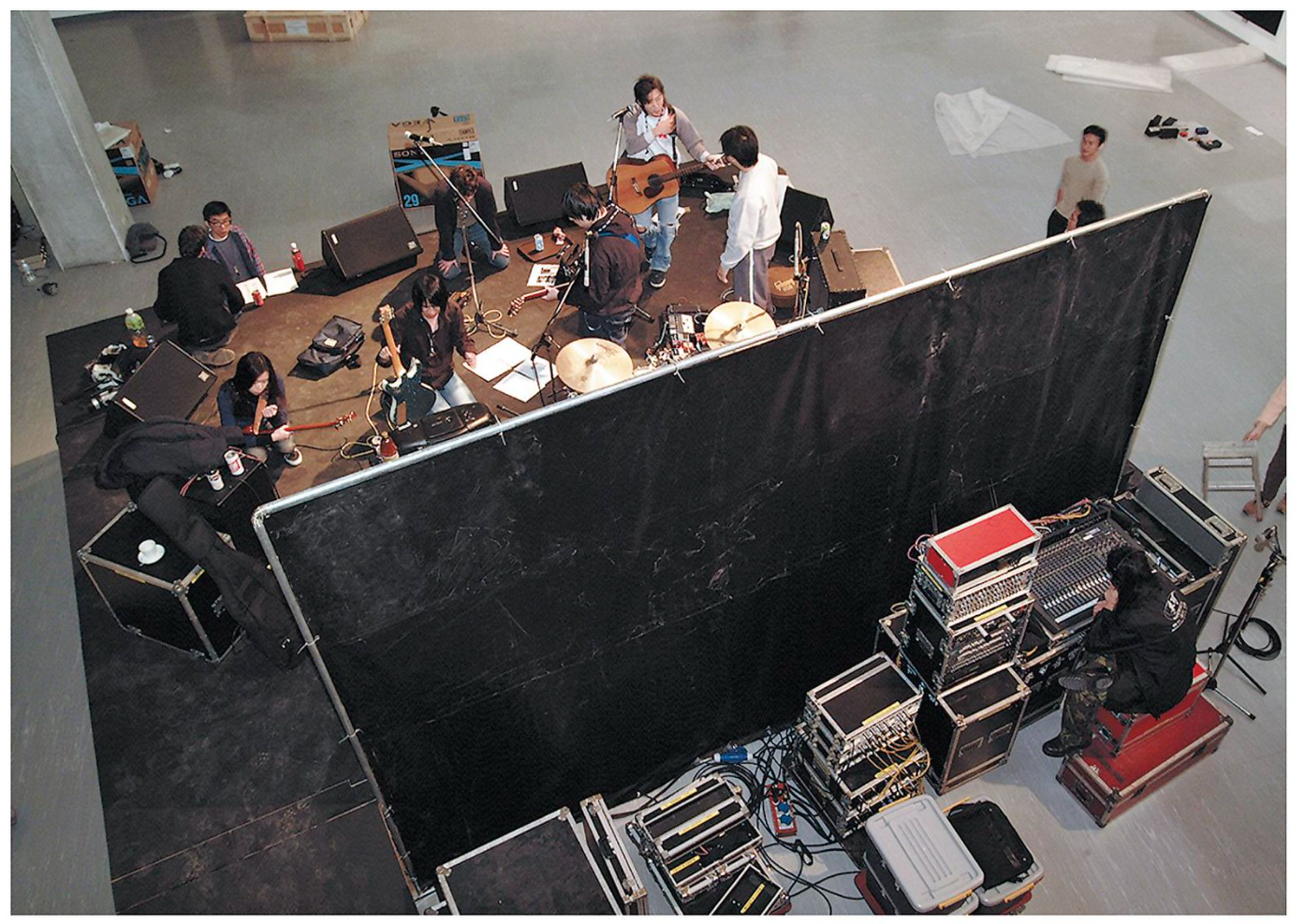

November 2002. Members of the Taiwanese band Le petit nurse undergo five consecutive days of intensive rehearsals in order to learn the songs from the Basque Radical Rock scene’s punk repertoire. This “radical translation exercise”, as described by Carles Guerra in the catalogue of the Gure Artea award, which Garmendia received for this piece in 2003, takes place on a stage built specifically for this purpose and designed by the artist in a spacious exhibition room of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, a venue of the 3rd Edition of The Taipei Biennial, titled Great Theatre Of The World (curated by Bartomeu Marí and Chia Chi Jason Wang).

Kolpez/Kolpe consolidates a filming style that Garmendia practiced in his previous works, while also inaugurating new interventions in the montage that would soon become his signature. On one hand, the shooting is articulated around a group of texts (songs by the bands Zarama, Kortatu and Eskorbuto) which the Taiwanese band members must internalise in a short period of time. On the other hand, the resulting film is assembled following a logic that brings together fragments of lived time during the filming, which are connected by fades to black and abrupt cuts. A “hatchet” editing that attempts to escape the documentary format which was ubiquitous in the art of the period.

The elusive nature of this work’s recording, nevertheless, facilitates the intersection of multiple temporalities: the recent past, spectrally present through the sound of the songs; the action’s present, which reinterprets said past from a different place and time —a present that becomes absent at times, due to the sound being taken off certain scenes—, and lastly, the time of the shooting echoing in the museum space during the days of the exhibition setup. The video even proposes a wider intertextual connection: the portrait of the spirit of a period mediated by the Basque Radical Rock scene as the remains of the Basque context’s paranormal reality, as Joseba Zulaika would call it. Next to it, a global image, a blue-glitter and Union Jack pastiche typical of the early 00s post-MTV generation.

The text emerges from the margins, at its own pace, following its own slow and incomplete logics of the exchange between copy and original. The image has its own cadence, marked by the unstable assimilation of a homogeneous time, constantly accelerating, as it seems, but which will actually soon be forgotten. This is even more evident now, almost 20 years since the making of Kolpez/Kolpe. In the light of the present —a present in which, as Mark Fisher said, the sense of future shock has disappeared—, this work demonstrates the sound repertoire from the 70s and 80s remains an icon, whereas the defiant insolence of some forms of artistic and exhibition production from the beginning of the 2000s has disappeared.

Related bibliography

→ Kolpez Kolpe. Barcelona, Galería T4, 19 November 2003 – 24 January 2004.

→“Goierri konpeti” : Iñaki Garmendia y Asier Mendizabal. Bordeaux, Galerie du Triangle, 5 – 20 June 2003.

→ Després de la noticia : documentals postmèdia. Barcelona, CCCB-Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, 23 July – 2 November 2003.

→ Cine y casi cine. Madrid, MNCARS-Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 13 November – 19 December 2003.

Carles Guerra. “Kolpez Kolpe de Iñaki Garmendia”, Zehar, San Sebastian, no. 52, 2004, p. 65.

Critique by Carles Guerra of Garmendia’s exhibition Kolpez Kolpe, Galería_T4, Barcelona (19/11/2003-24/01/2004) in Zehar magazine, Arteleku. Guerra sees Kolpez Kolpe as “an exercise which puts Basque Radical Rock through an exercise of ventriloquism”, resulting in what might be called “a radical translation”. Download article.

TB esku-hartzeak, 1999-2004 [Exh. cat.]. Vitoria City Council, 2004, p. 10.

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

→ Iñaki Garmendia : kolpez kolpe. Madrid, Matadero-Centro de Creación Contemporánea, 2 – 30 June 2009.

ARCO ’09. Madrid: ARCO/IFEMA, Feria de Madrid, 2009, pp. 224, 578.

Selected #4 : Una font per els amants del videoart : a source for videoart lovers. [S.l.] : Screen Projects, [2009], p. 30.

→ Iñaki Garmendia : Kolpez Kolpe. Lleida, Centre d’Art La Panera, 10 March – 25 April 2010.

“Kolpez Kolpe. Iñaki Garmendia sobre los denominadores comunes de la juventud”, nexo5.com. Magacín digital de la cultura contemporánea, Madrid, 16/03/2010.

La sombra del habla : colección MACBA. [Exh. cat.]. Seoul, Kungnip Hyondae Misulgwan, cop. 2010, p. 194-195

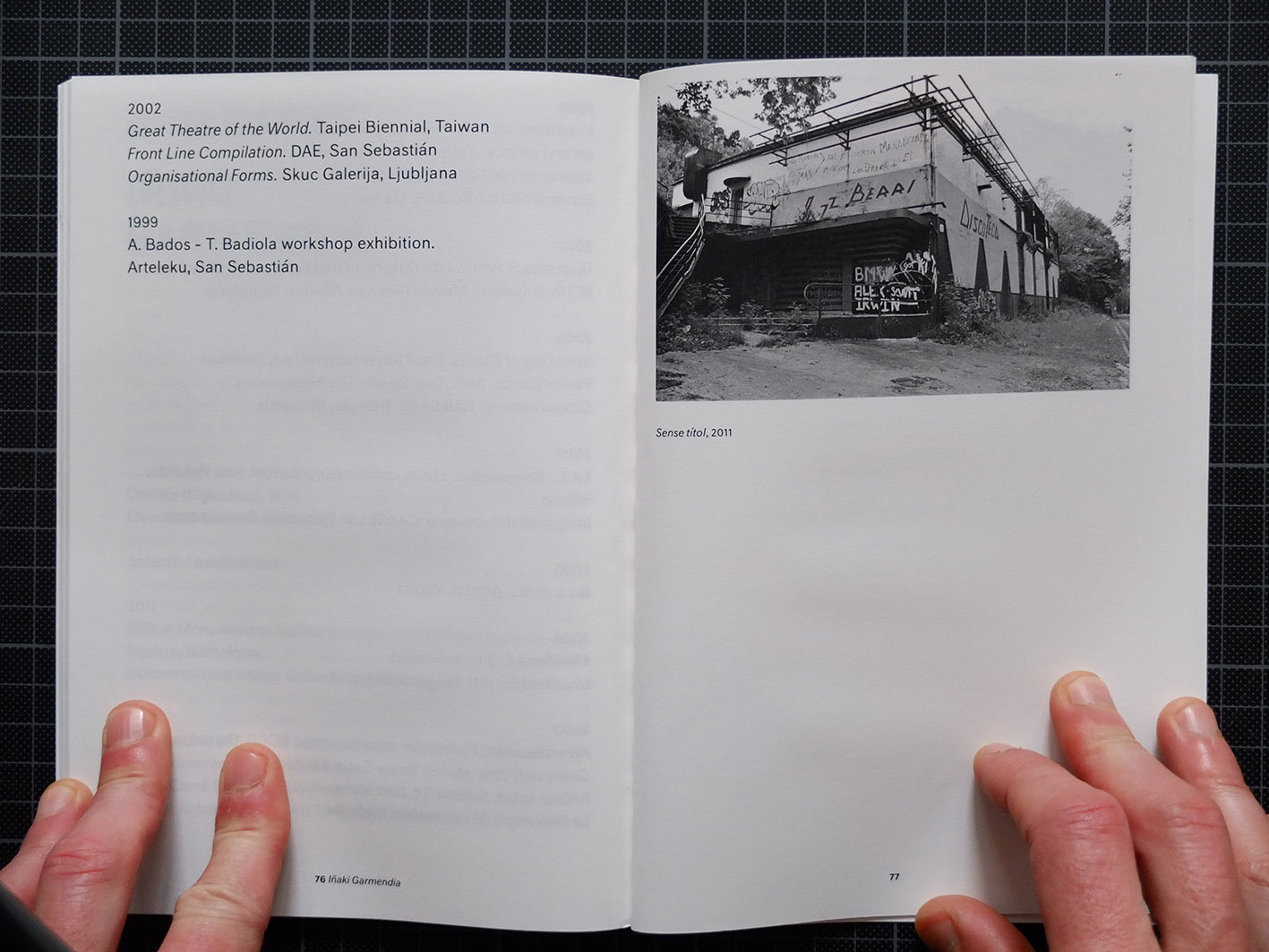

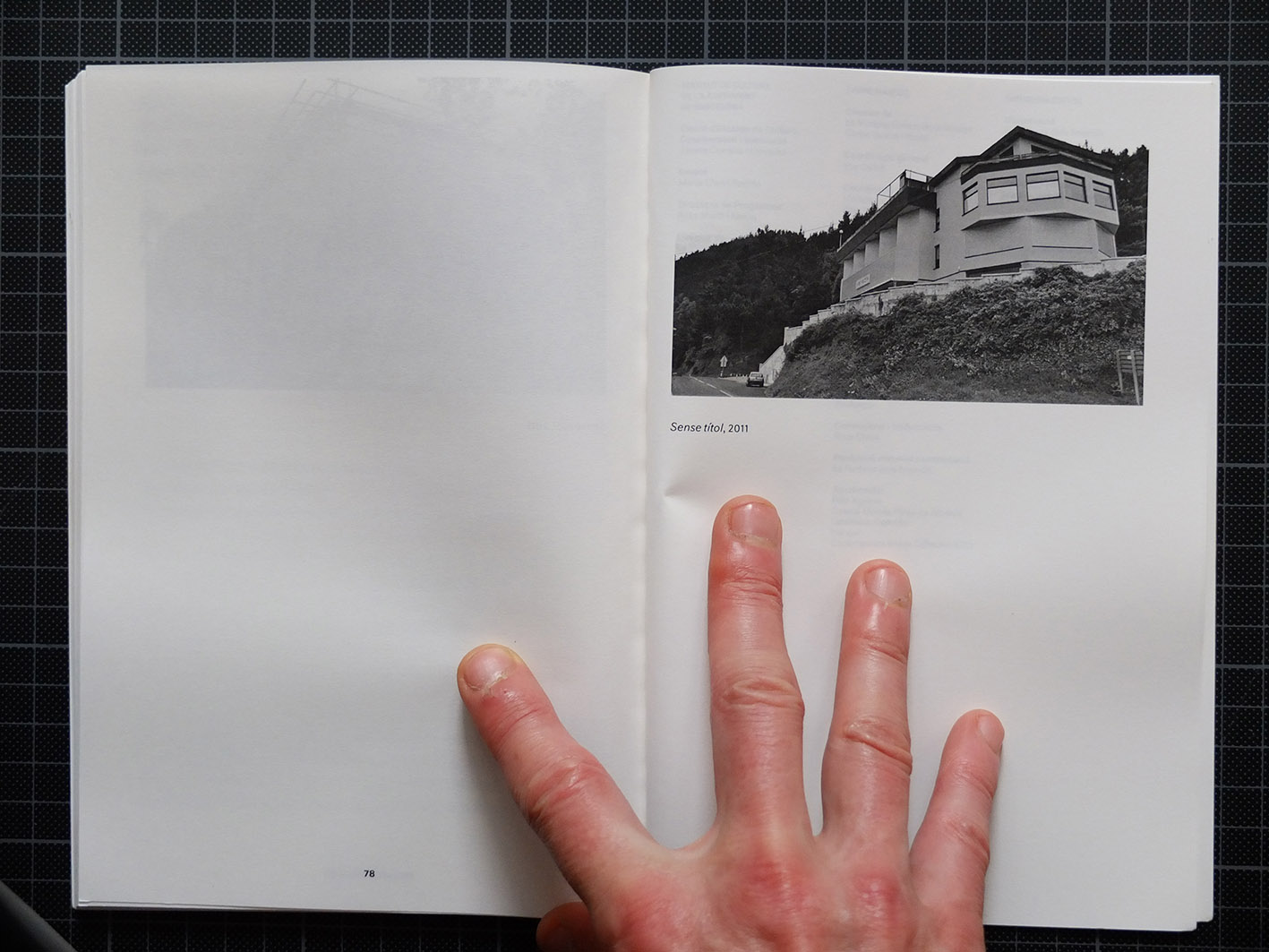

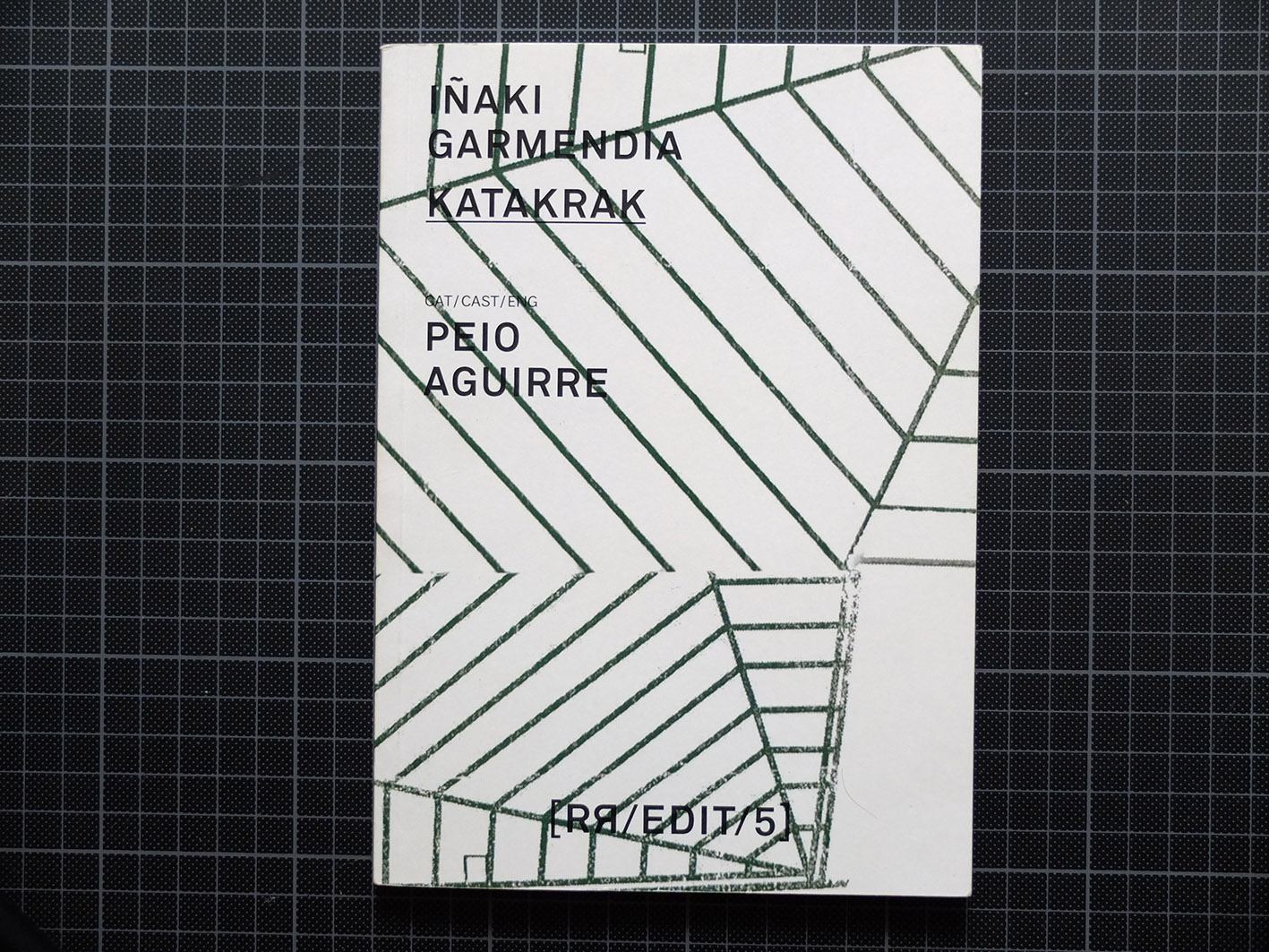

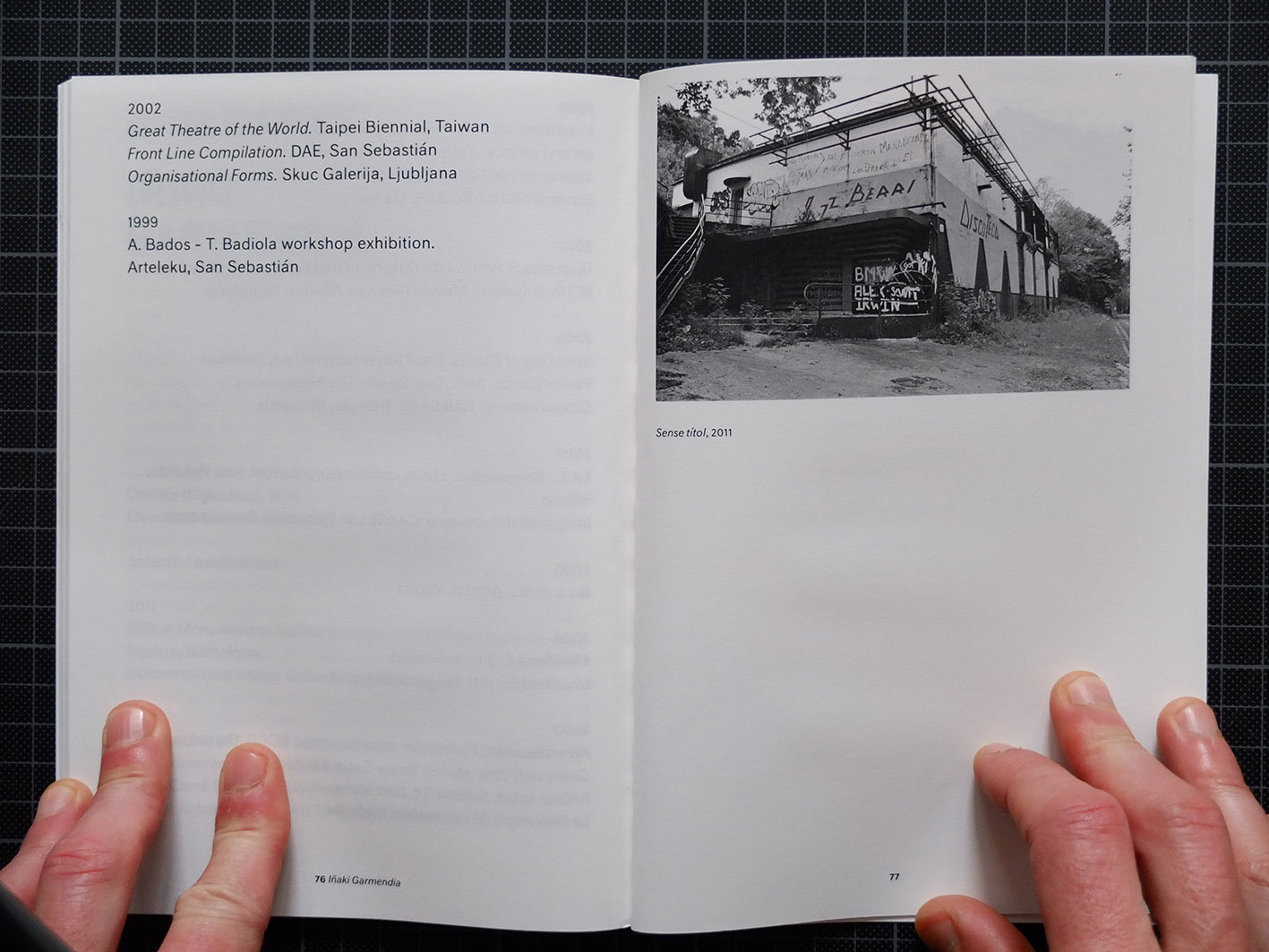

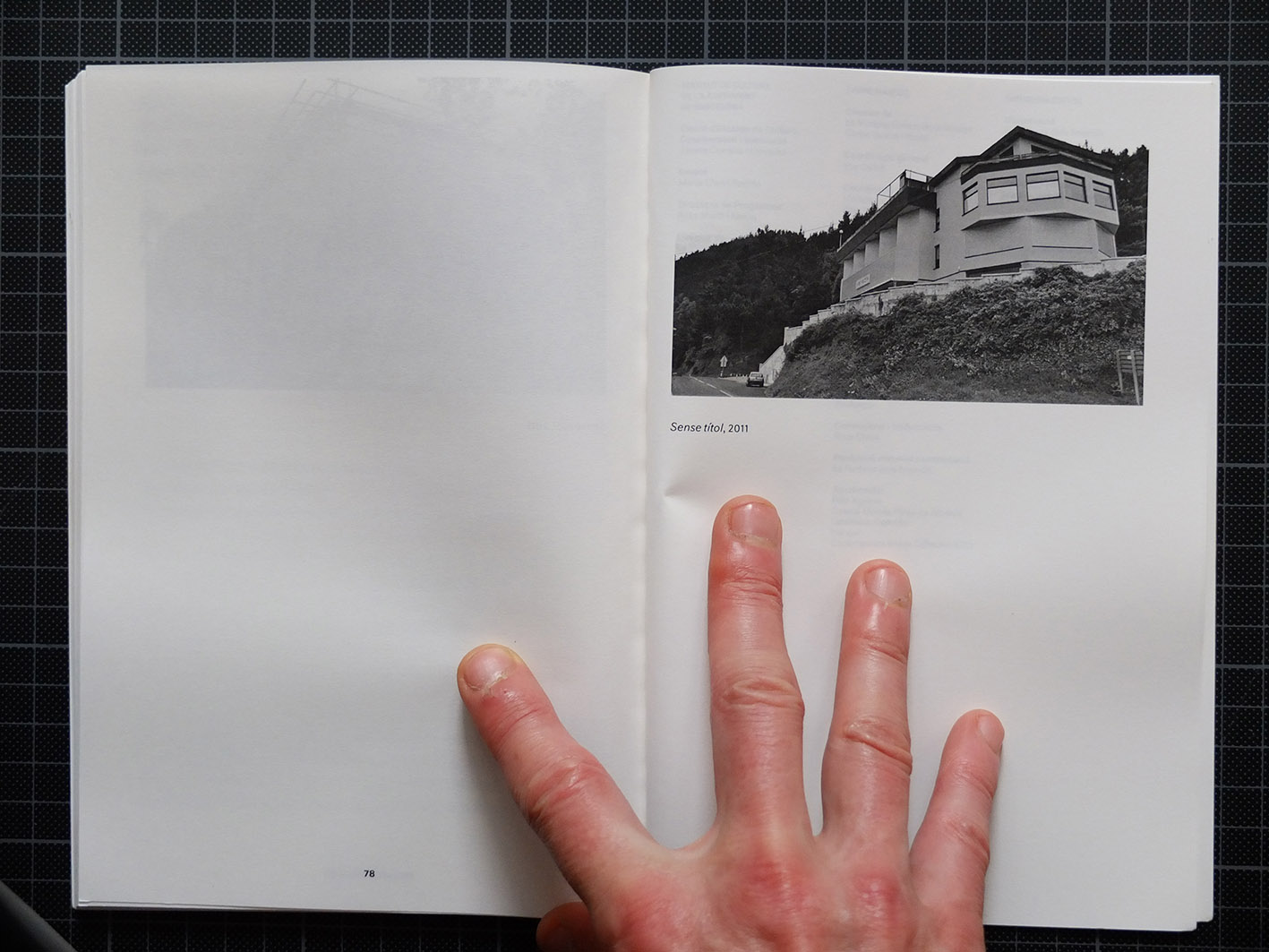

KATAKRAK: Iñaki Garmendia. [Exh. cat.]. Barcelona: Barcelona City Council, Institut de Cultura, 2011.

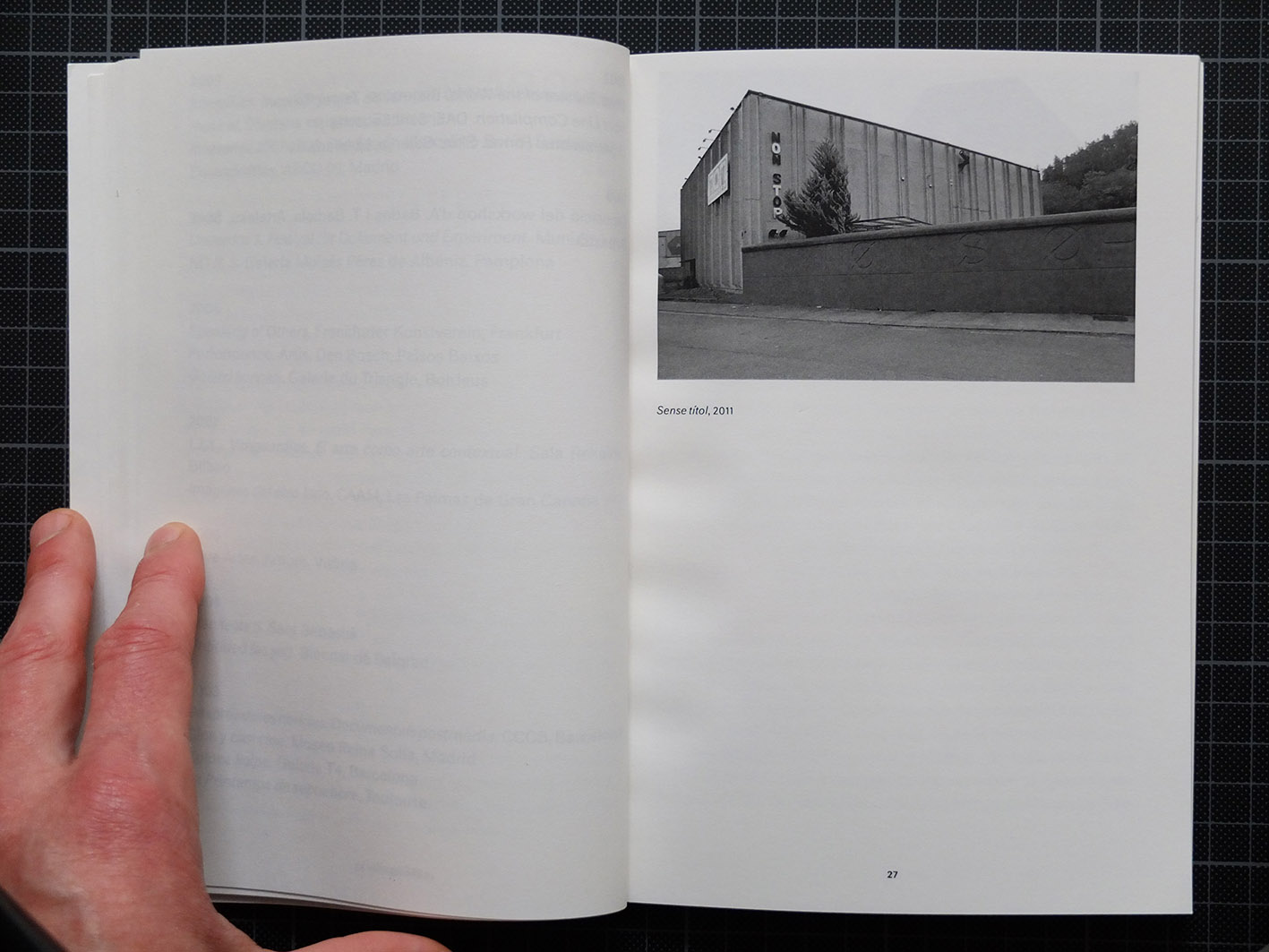

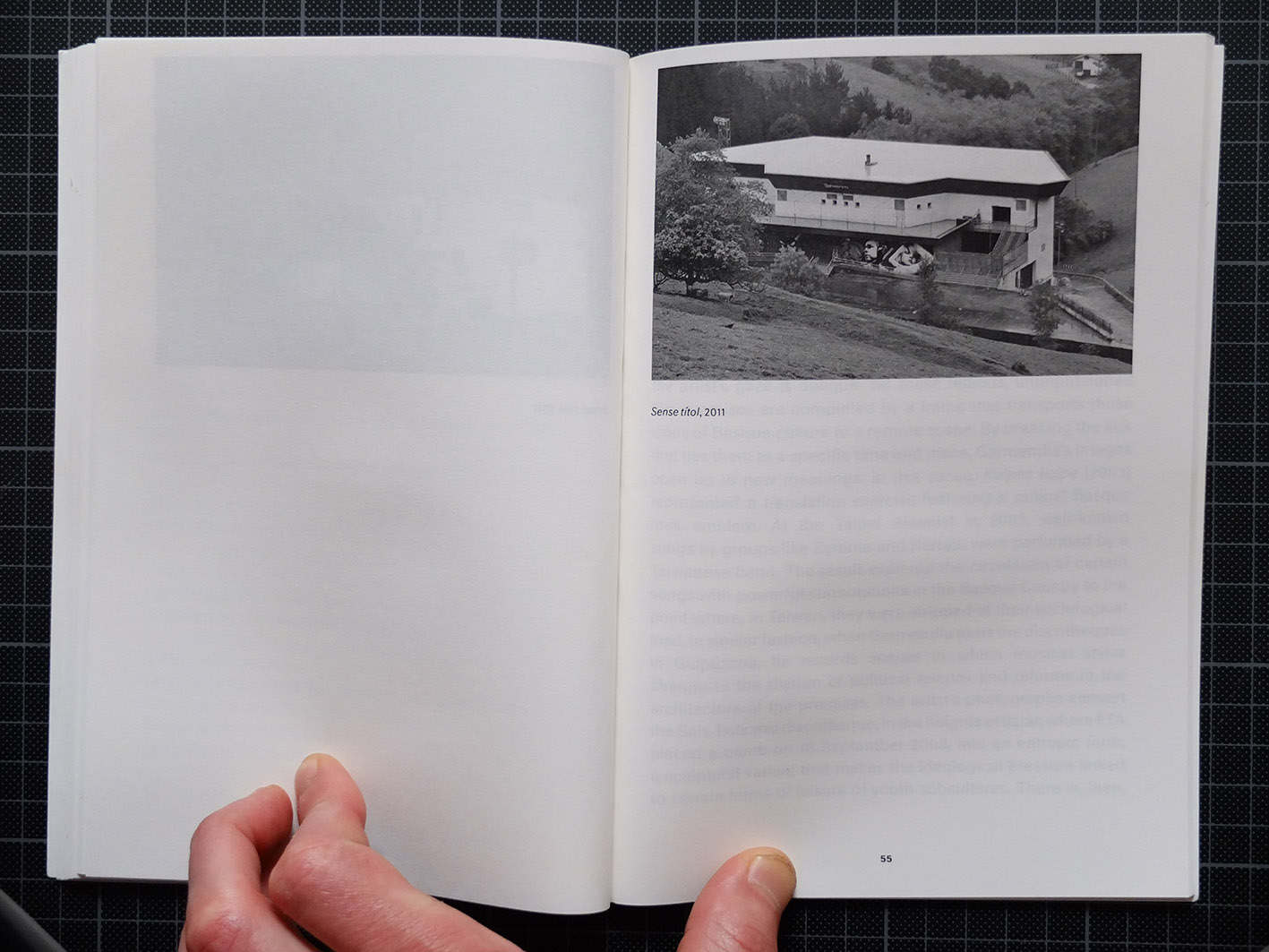

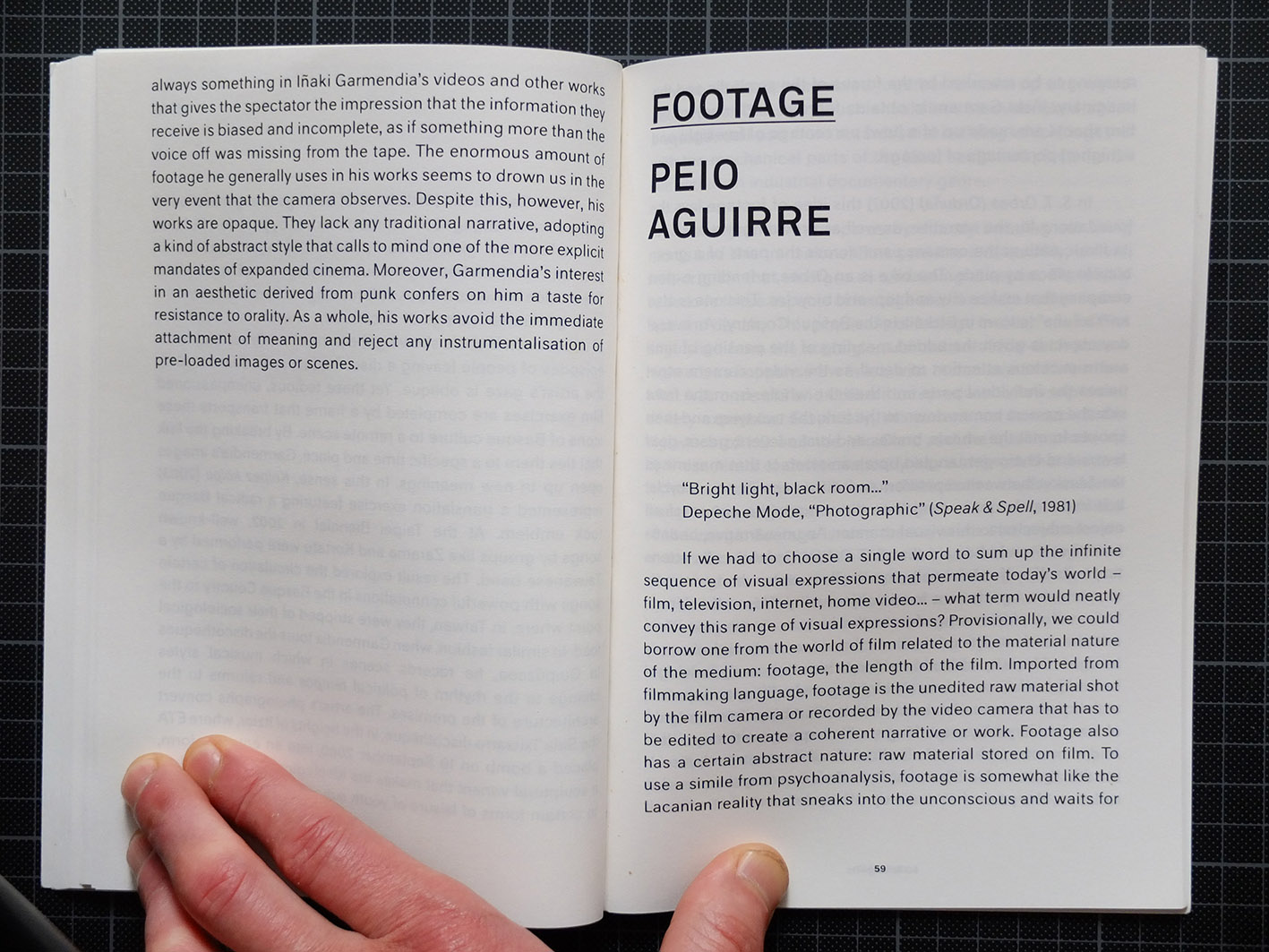

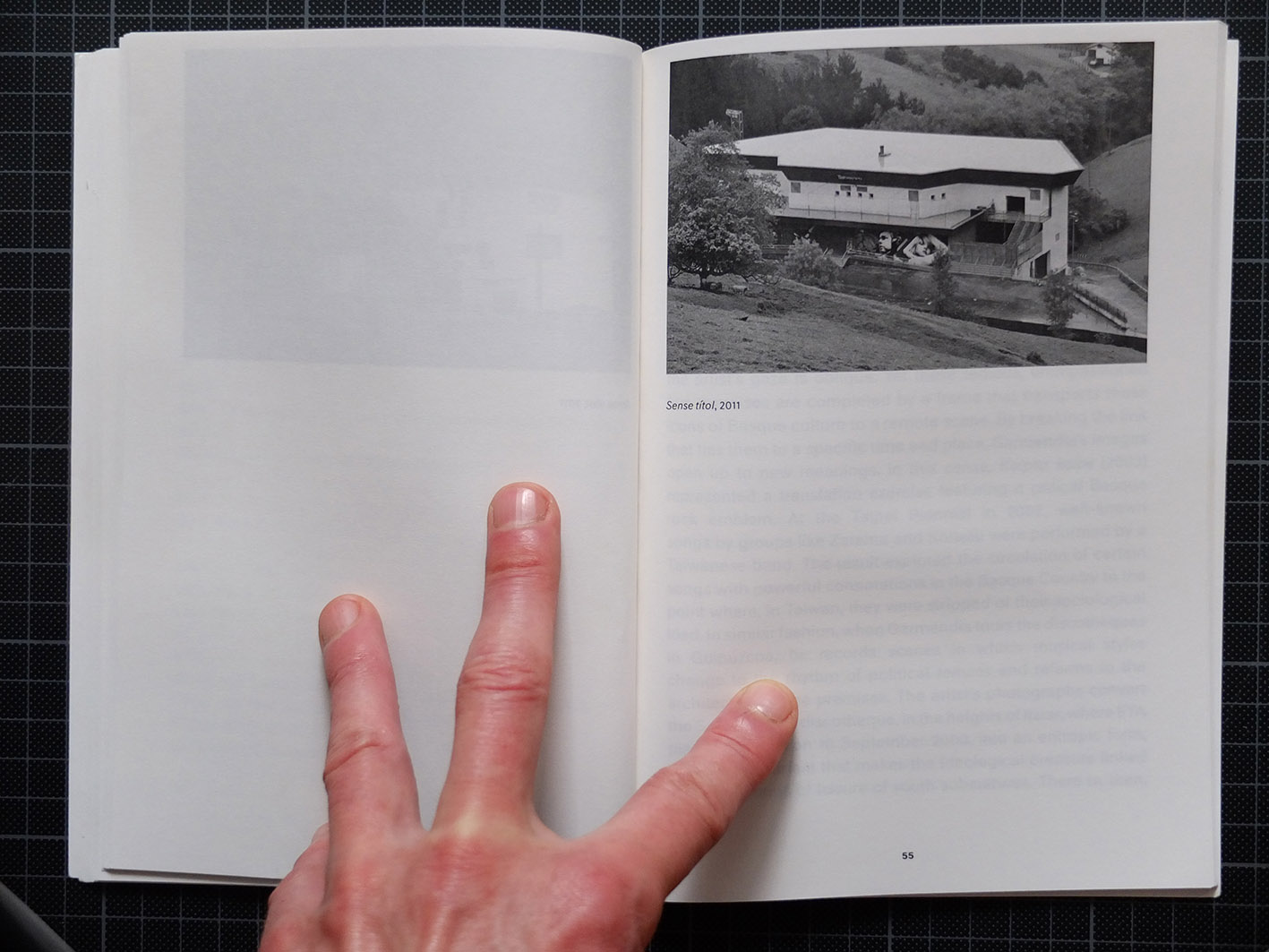

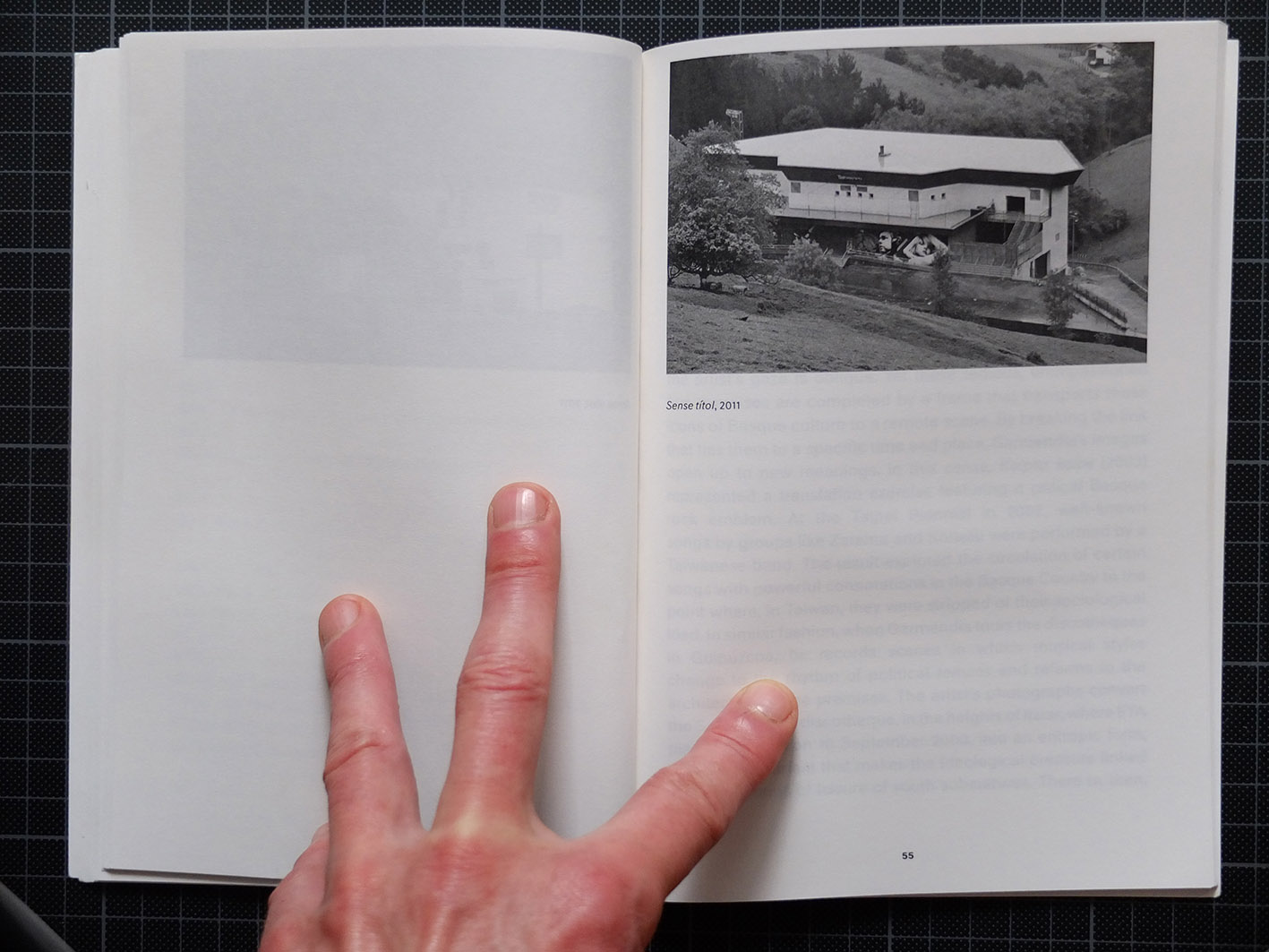

Catalogue of solo exhibition at Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, titled Katakrak (14/07-02/10/2011) including “Metraje”, a text by Peio Aguirre, in Spanish, Catalan and English. The text basis its analysis of the artists work on videos such as S.T. (Orbea) (Orduña) (2007), Bolueta (2011), Kolpez Kolpe (2003), Harder, Faster, Better, Stronger (2004), and series such as Txitxarro (2000). With black and white images and brief artist bio.

Miren Jaio. A Collection of Prints: Visual Arts in the Basque Country. San Sebastian, Etxepare Basque Institute, D. L. 2012.

Efectos de superficie. Iñaki Garmendia y Leire Vergara. [Unpublished interview]. [Bilbao : Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2013].

Unpublished dialogue between Leire Vergara and Iñaki Garmendia for Garmendia. Maneros Zabala. Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Bilbao (31/10/2013-16/02/2014). The artist answers questions on his work process, the importance of the script, interrelationships between different works, text/image correspondence, and tensions between subject and object.

“Enfado del artista Iñaki Garmendia con el Guggenheim por no exponer una de sus obras”, naiz.info, 30/10/2013.

The Europe(n) Book. [Exh. cat.]. Berlin: jovis Verlag Gmbh, 2013, pp. 172-183.

M/Other Tongue. London : Tenderpixel & Tenderbooks, 2015, pp. 2, 18.

Punk : sus rastros en el arte contemporáneo. [Exh. cat.]. Madrid, Comunidad de Madrid ; Vitoria, Álava Provincial Government, 2015, pp. 78, 90, 92.

→ Después del 68 : arte y prácticas artísticas en el País Vasco, 1968-2018. Bilbao, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 7 November 2018 – 28 April 2019.

Después del 68 : arte y prácticas artísticas en el País Vasco, 1968-2018. [Exh. cat.]. Bilbao : Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 2018, pp. 103, 115, 116, 231, 281.

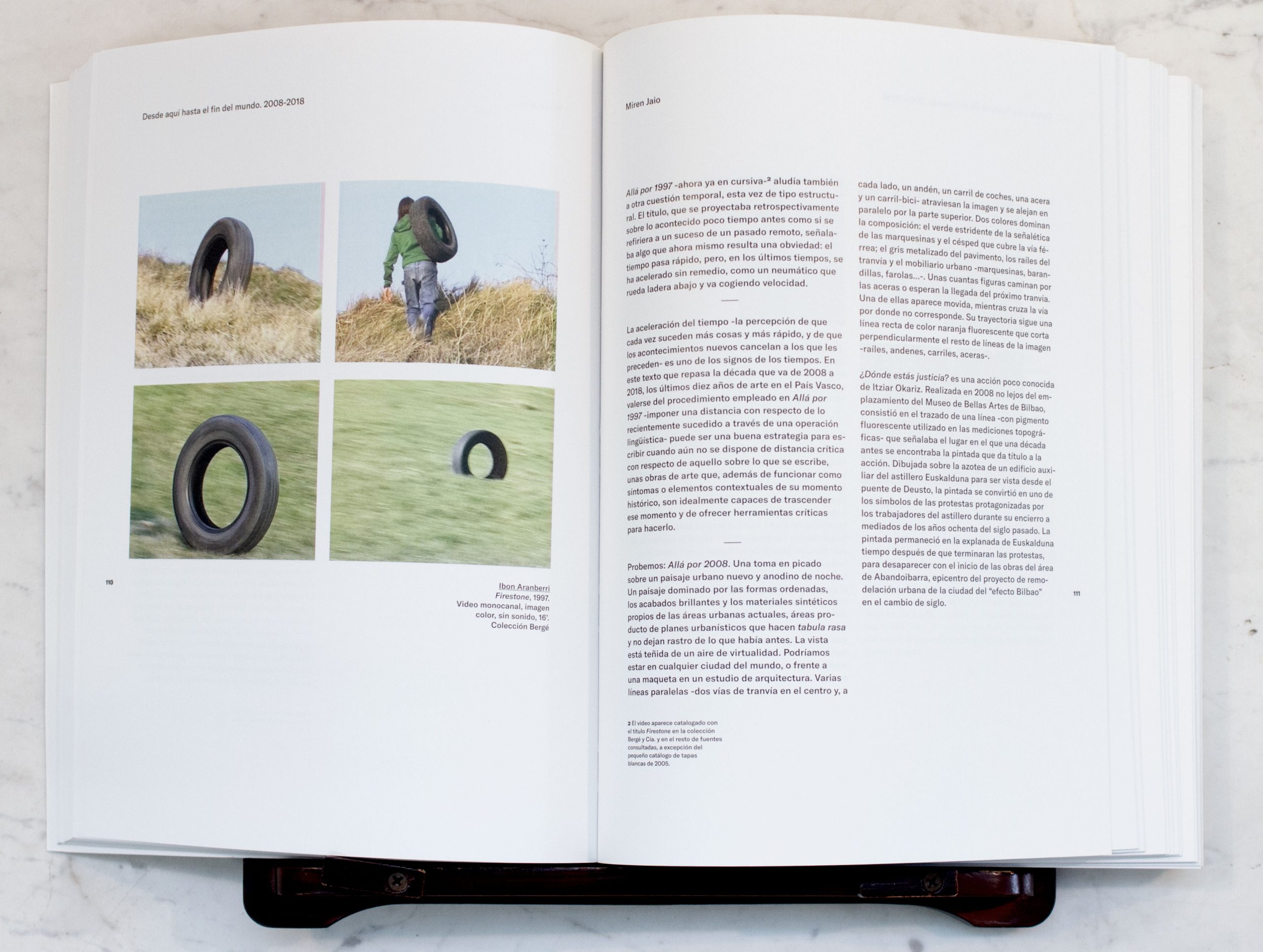

Exhibition catalogue for Después del 68, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (7/11/2018-28/04/2019), a revision of art practices in the Basque Country over the past 50 years via a selection of approximately 150 pieces, curated Miguel Zugaza, Miriam Alzuri and Begoña González. Includes still from Garmendia’s S.T. Orbea (2007), one of the selected works [p. 231]. Kolpez kolpe (2002-2003) is cited, with image, in Peio Aguirre’s article “Periodizando los años noventa. Sujetos deseantes” [p. 103]; and Miren Jaio, in the chapter “Desde aquí hasta el fin del mundo. 2008-2018” speaks of Garmendia’s exhibition Katakrak, Palacio de la Virreina, Barcelona (2011), and includes a view of the works Líneas de montaña (I-IV) and Sin título (verja) [pp. 115-116]. The cover of the exhibition catalogue for Garmendia; Maneros Zabala; Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (2013) is also reproduced [p. 281]. A chronology by Mikel Onandia includes references to Garmendia’s principal exhibitions and projects [pp. 400, 421, 428, 440, 443, 445, 451, 465, 469, 472, 476, 478, 479, 481, 482, 483, 487, 499, 503 y 505].

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

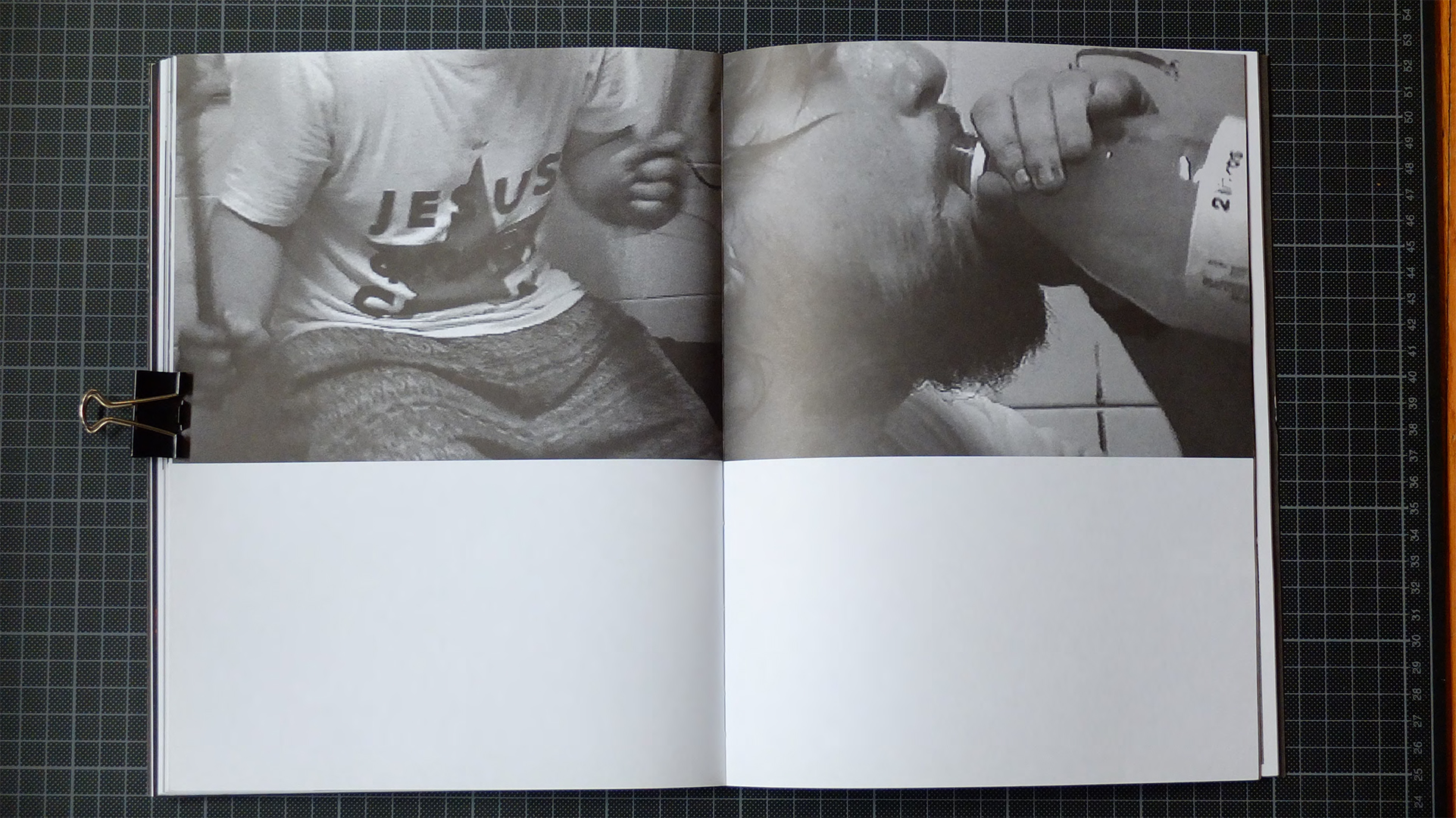

Two-channel video, with sound, colour

16’ 30’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

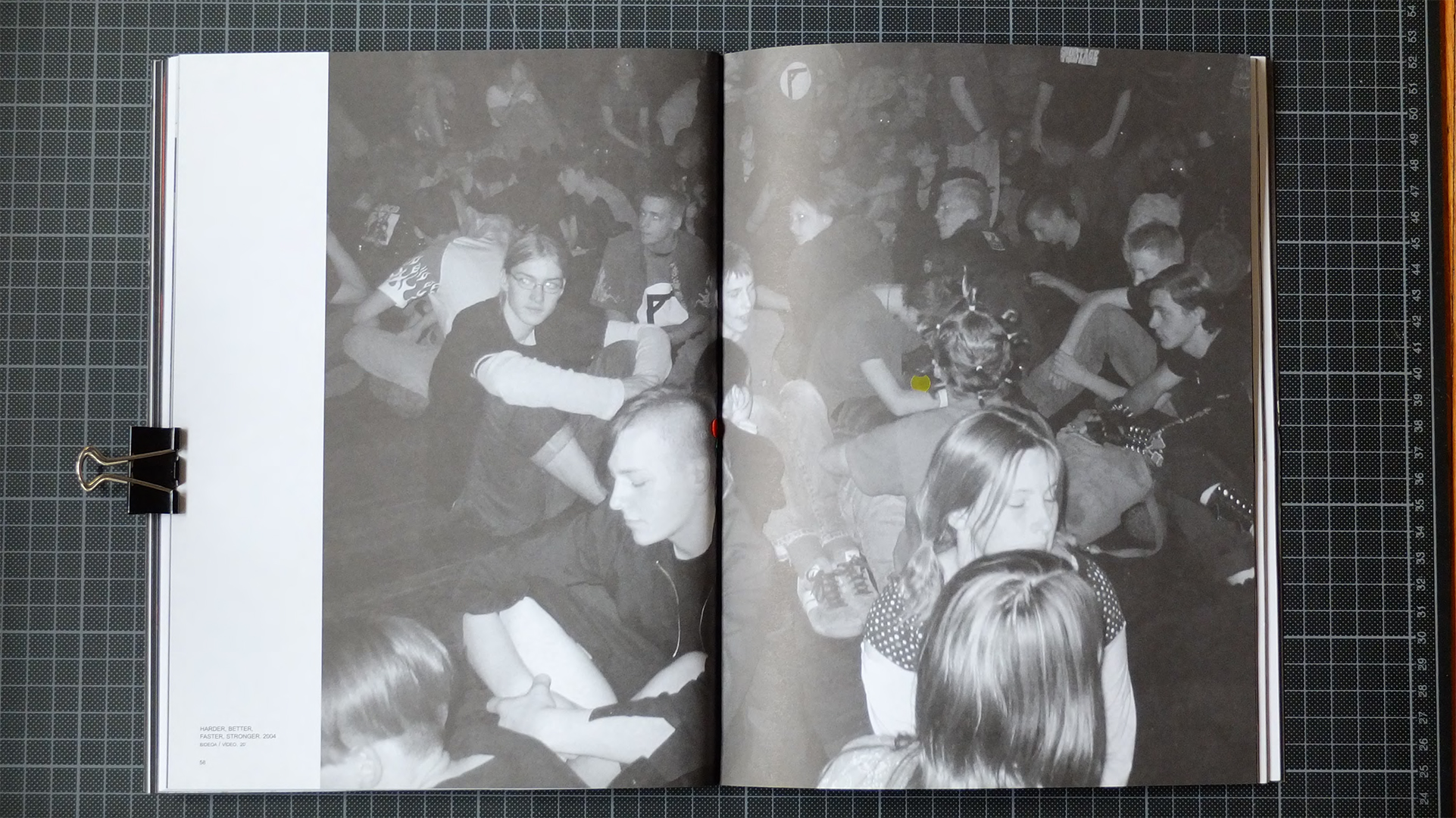

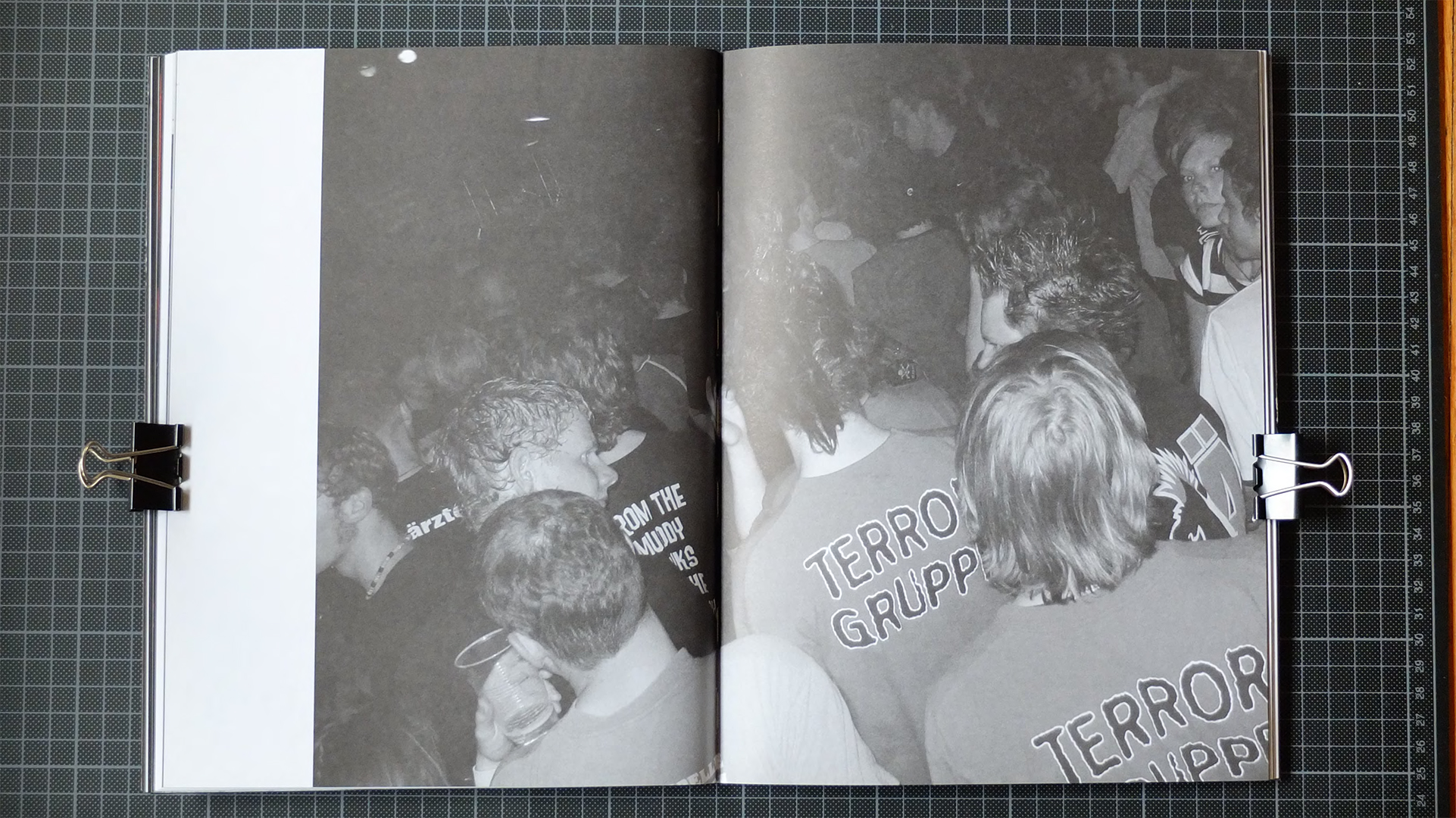

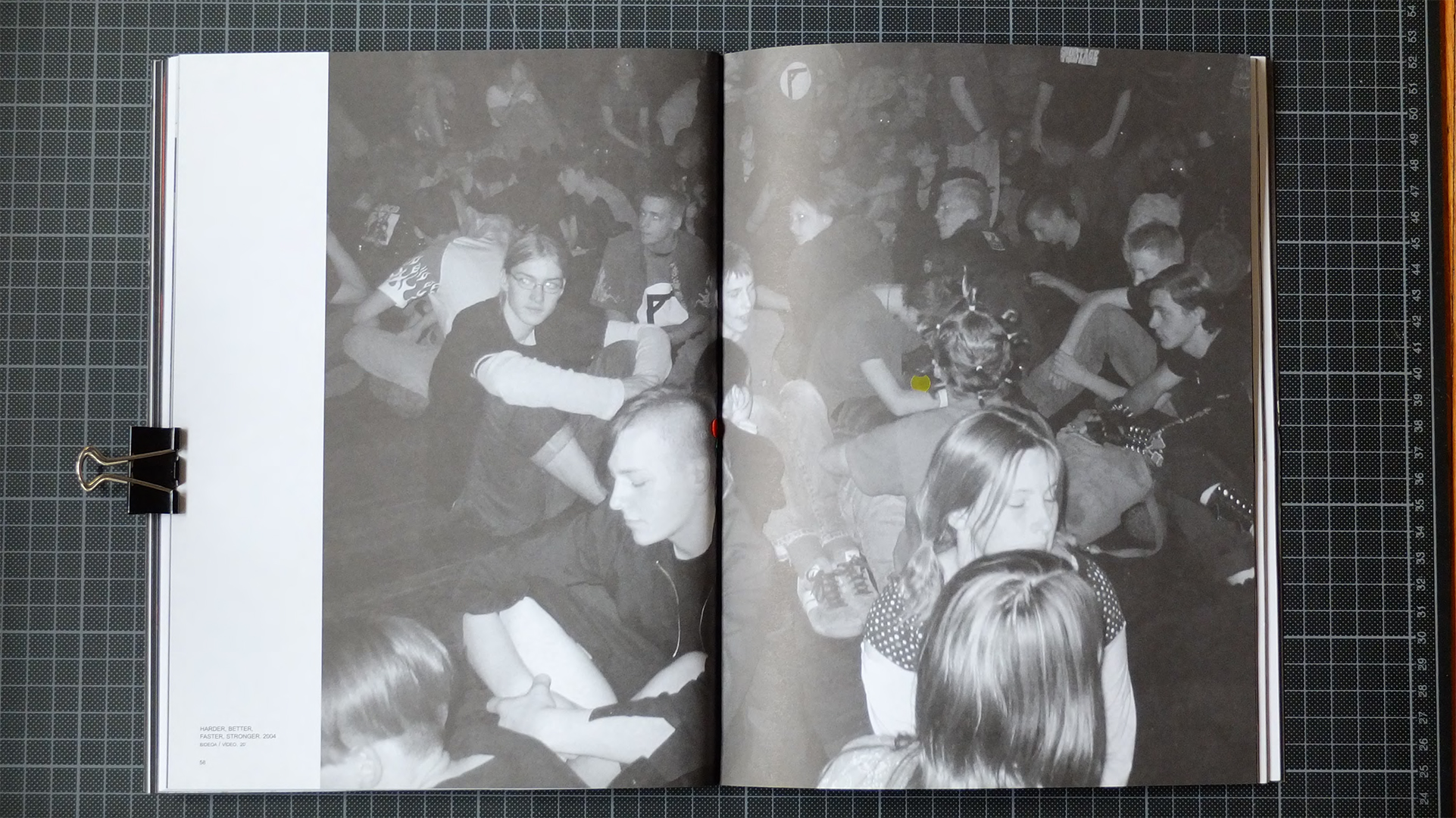

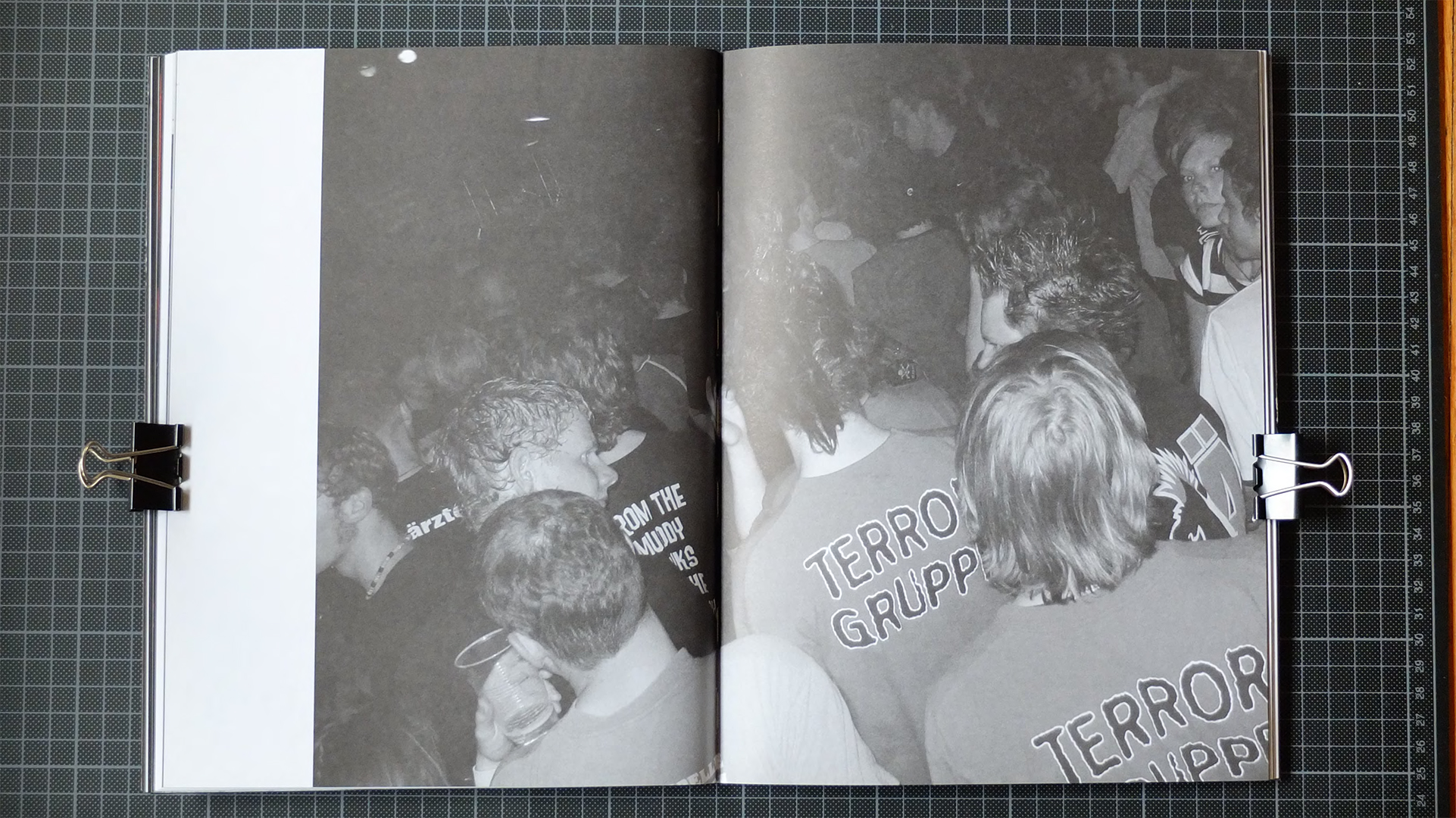

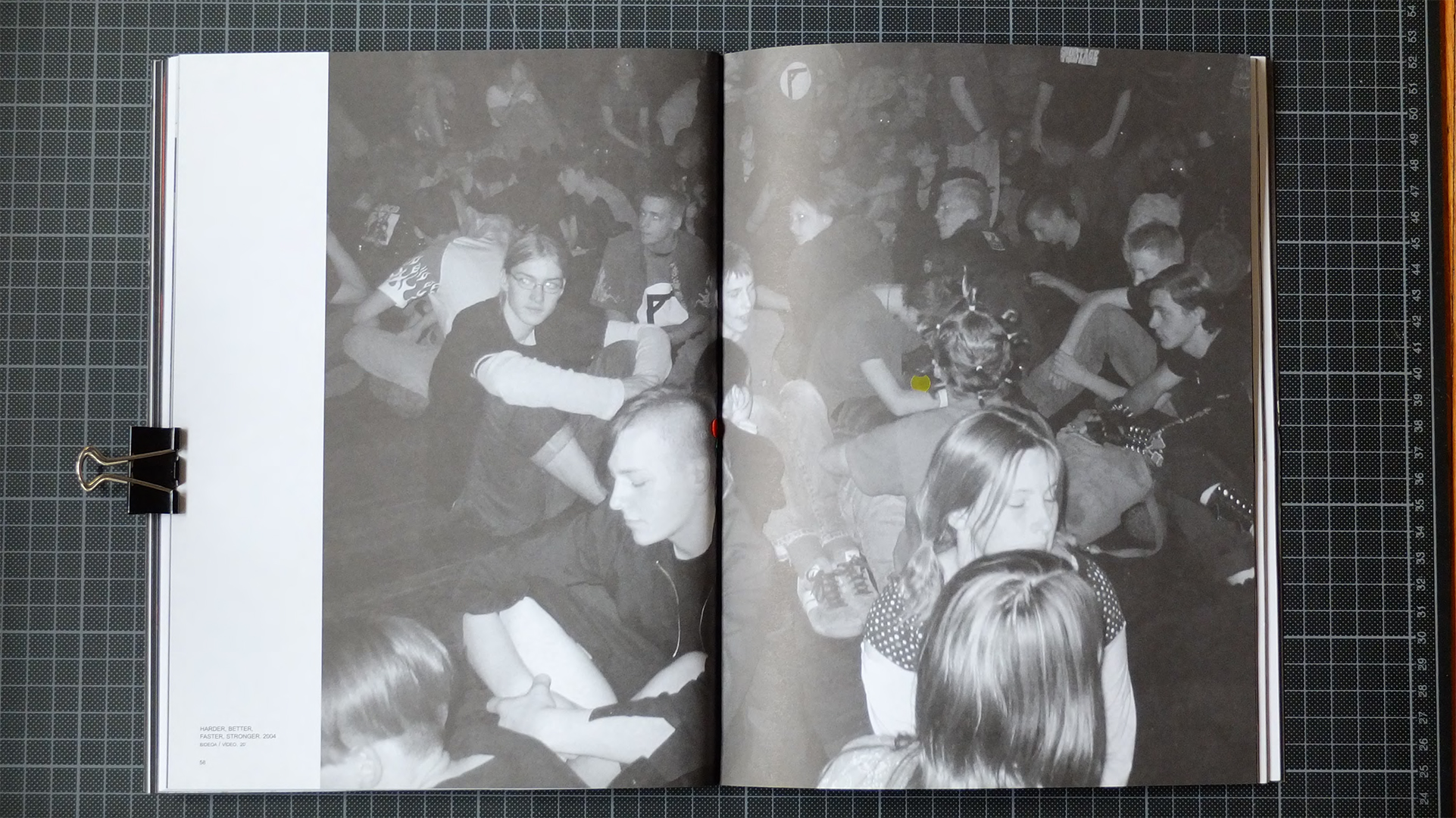

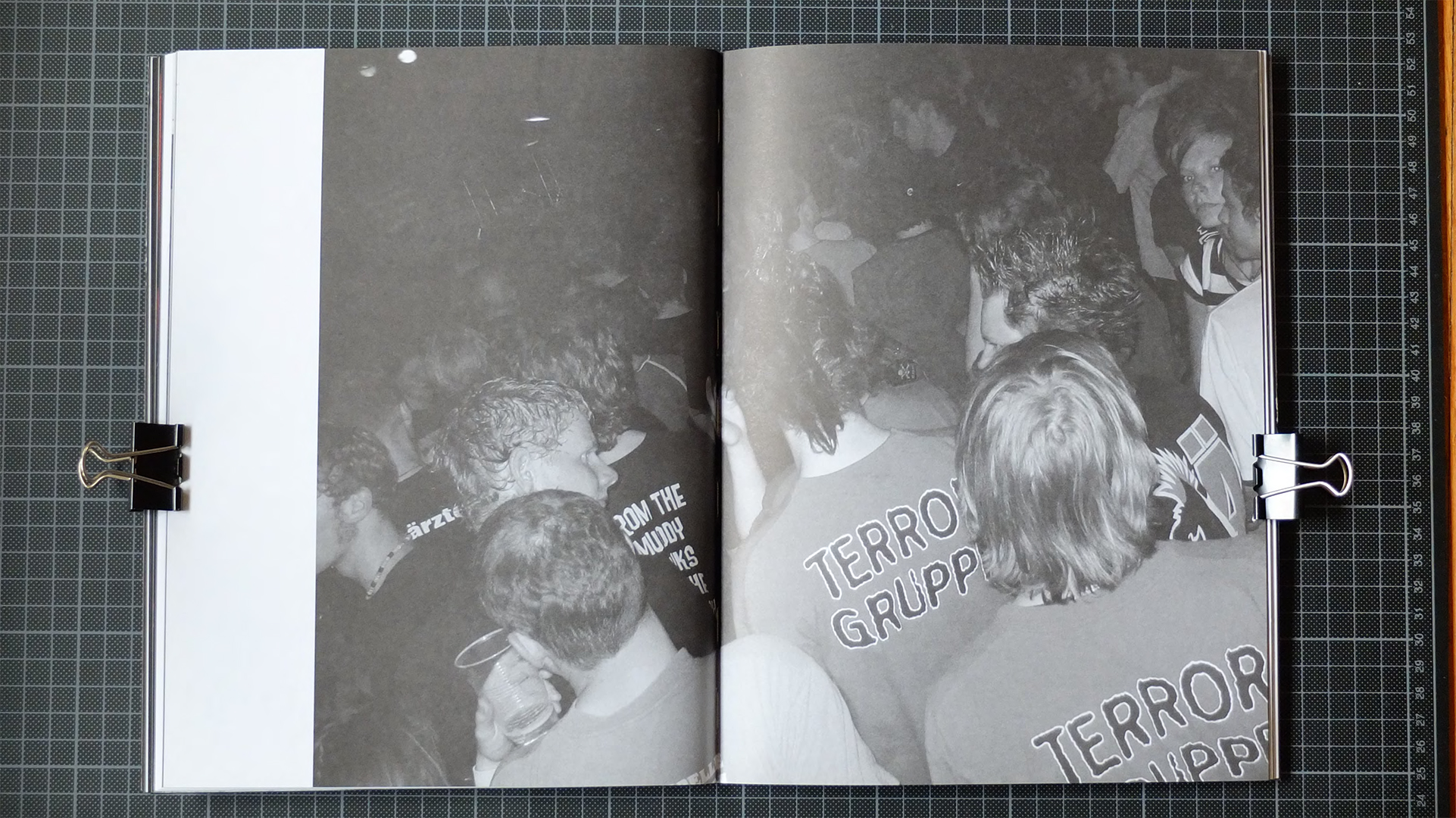

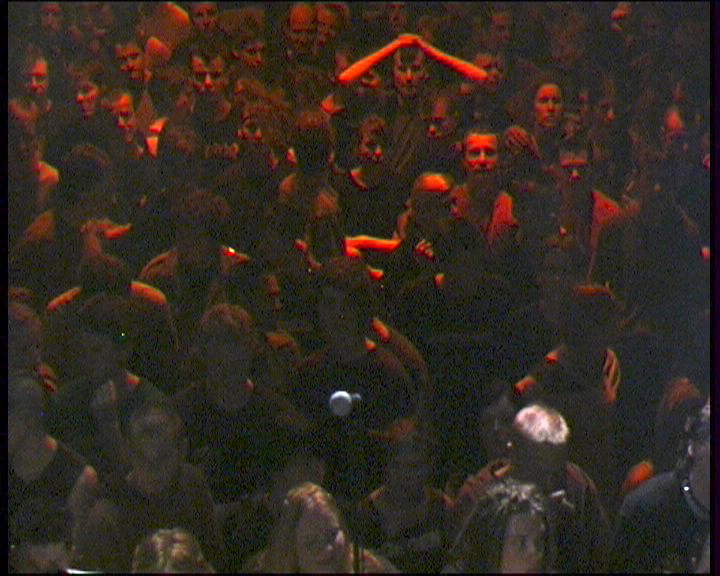

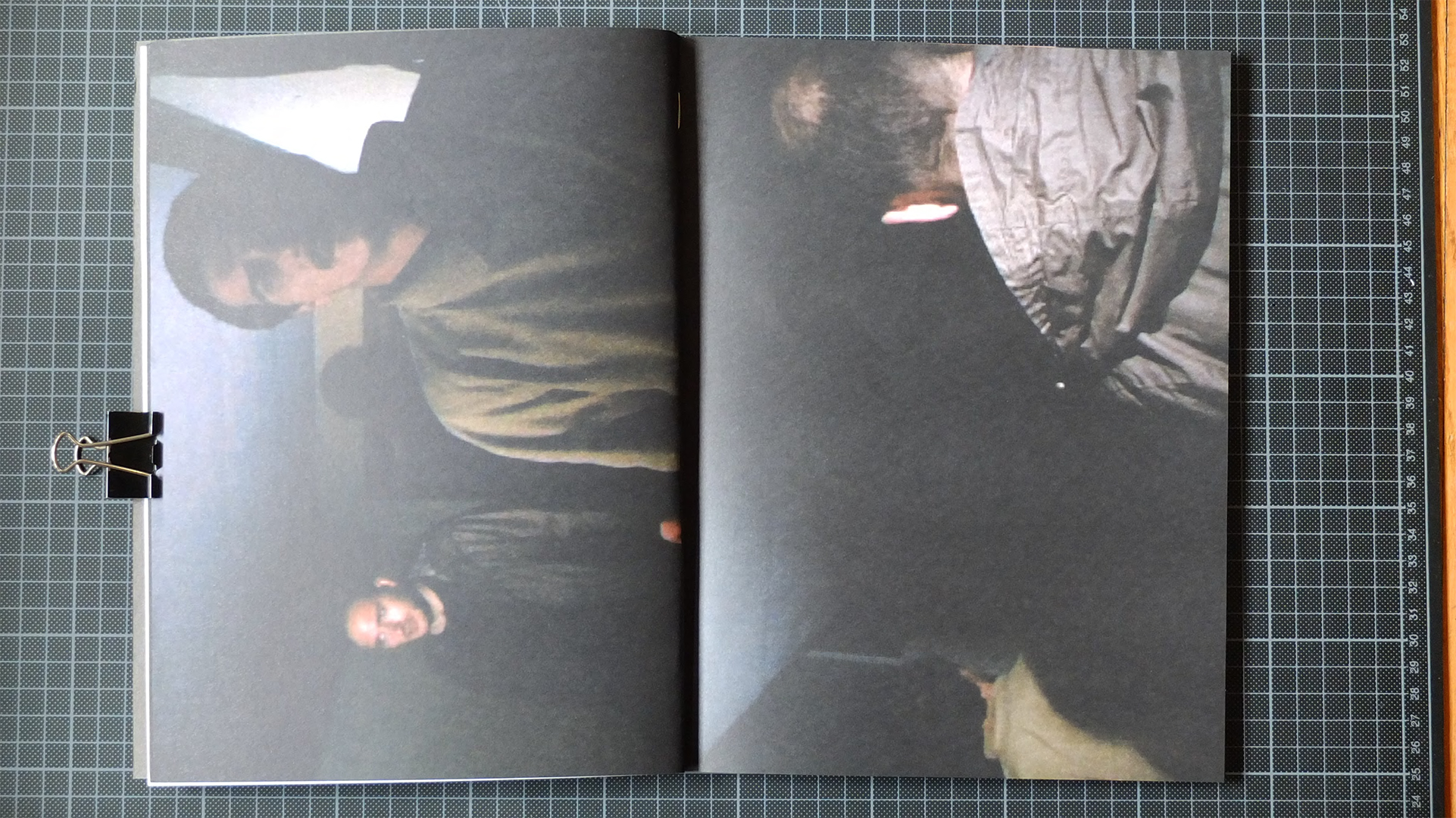

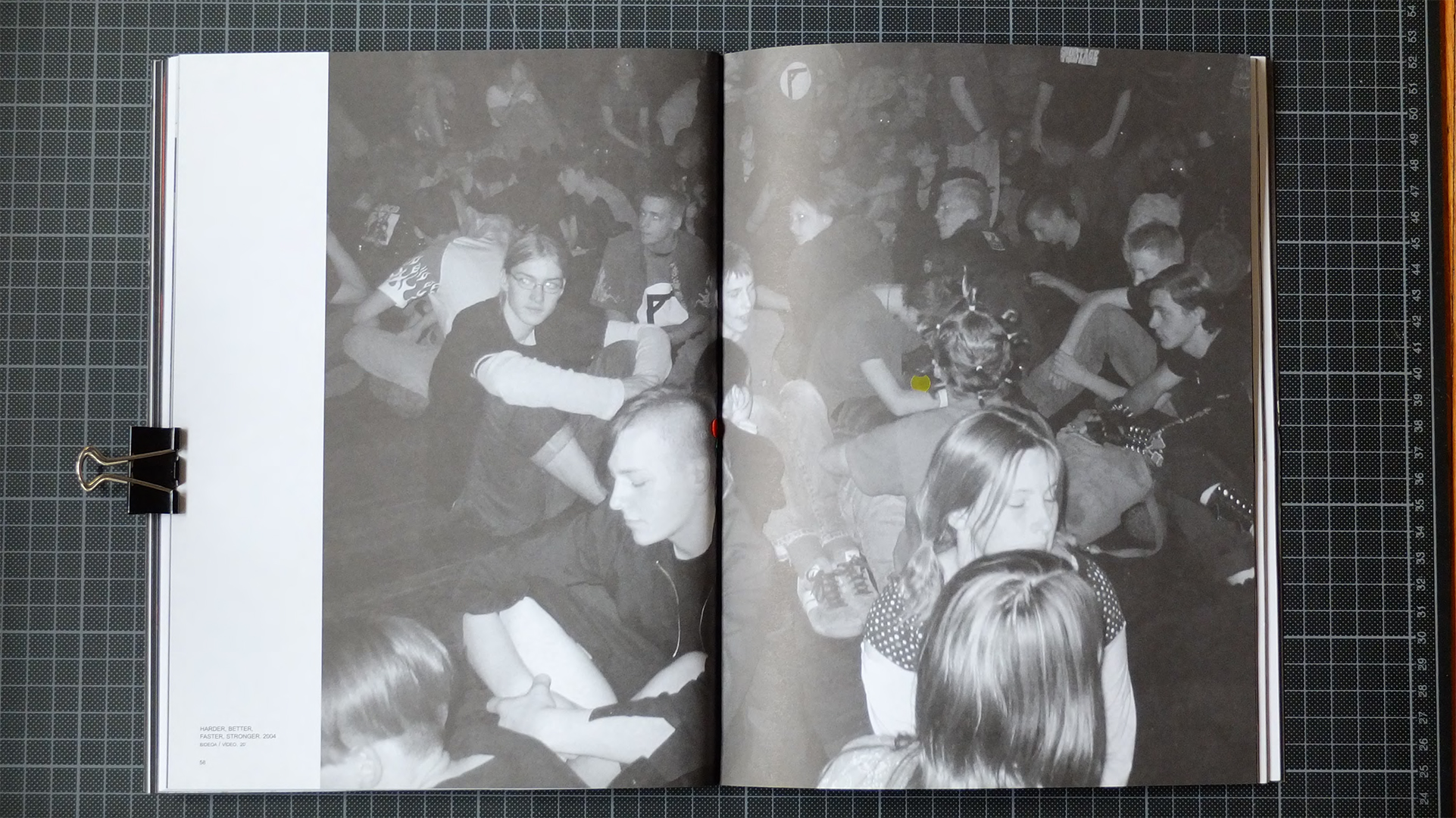

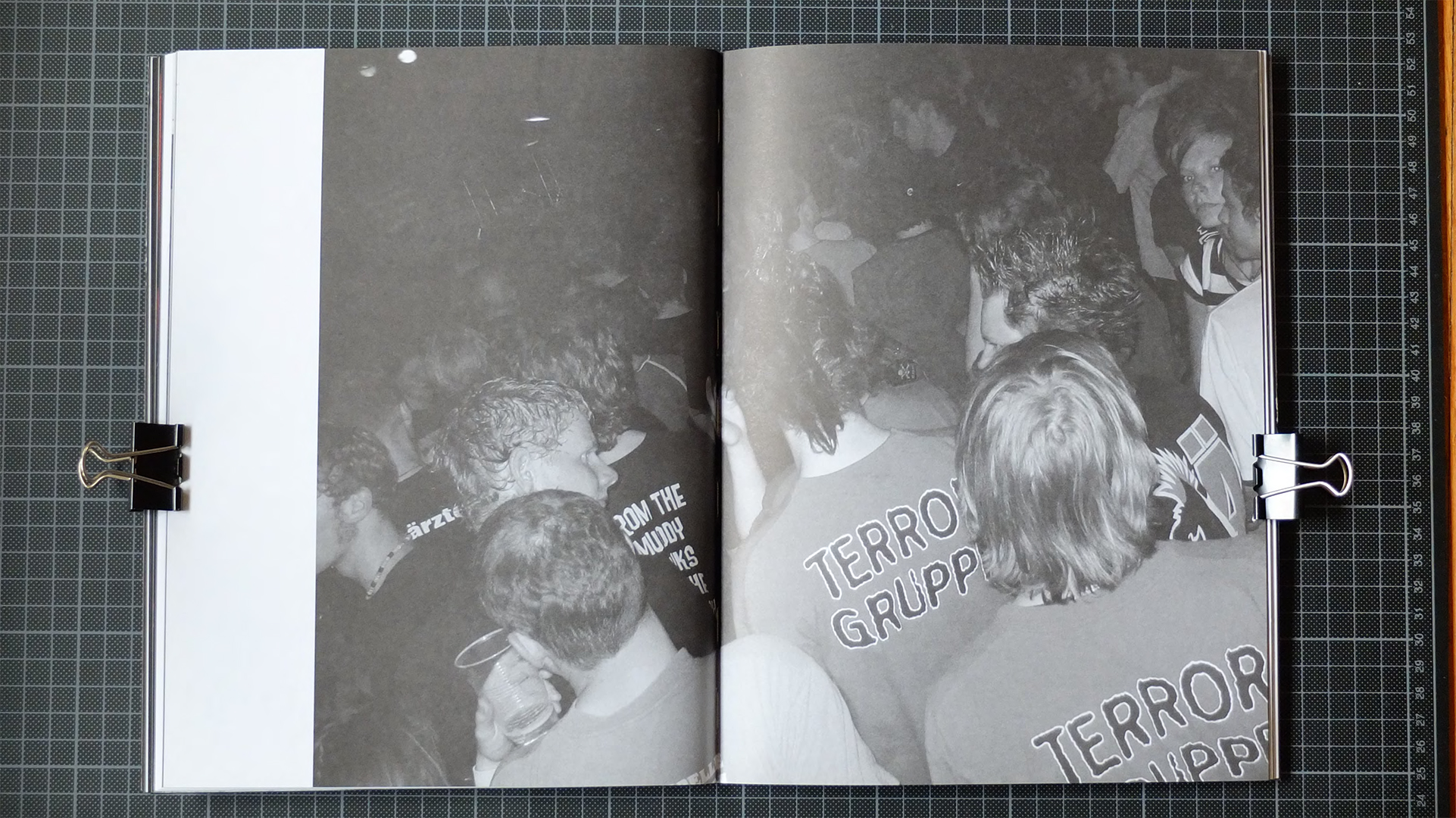

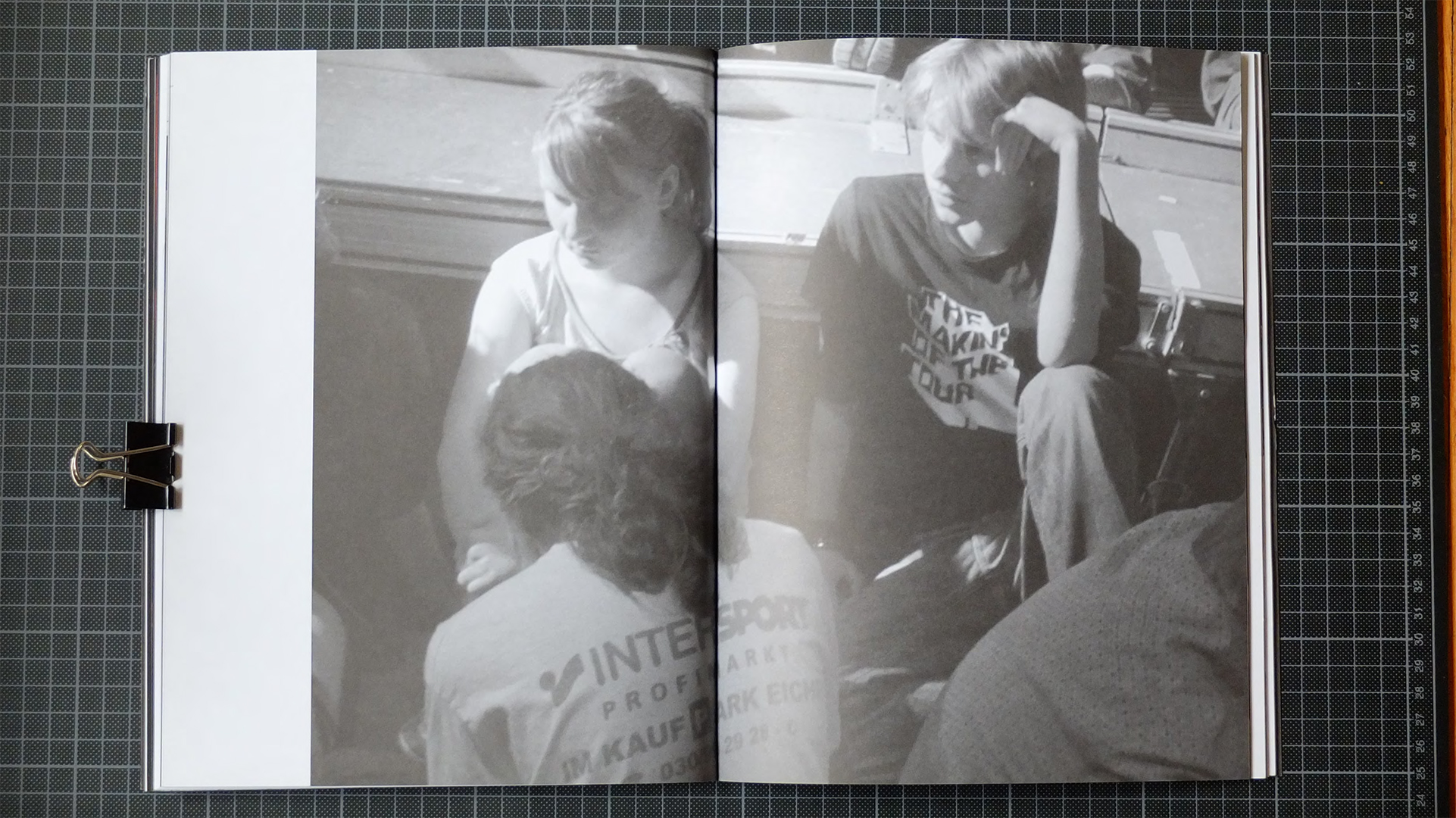

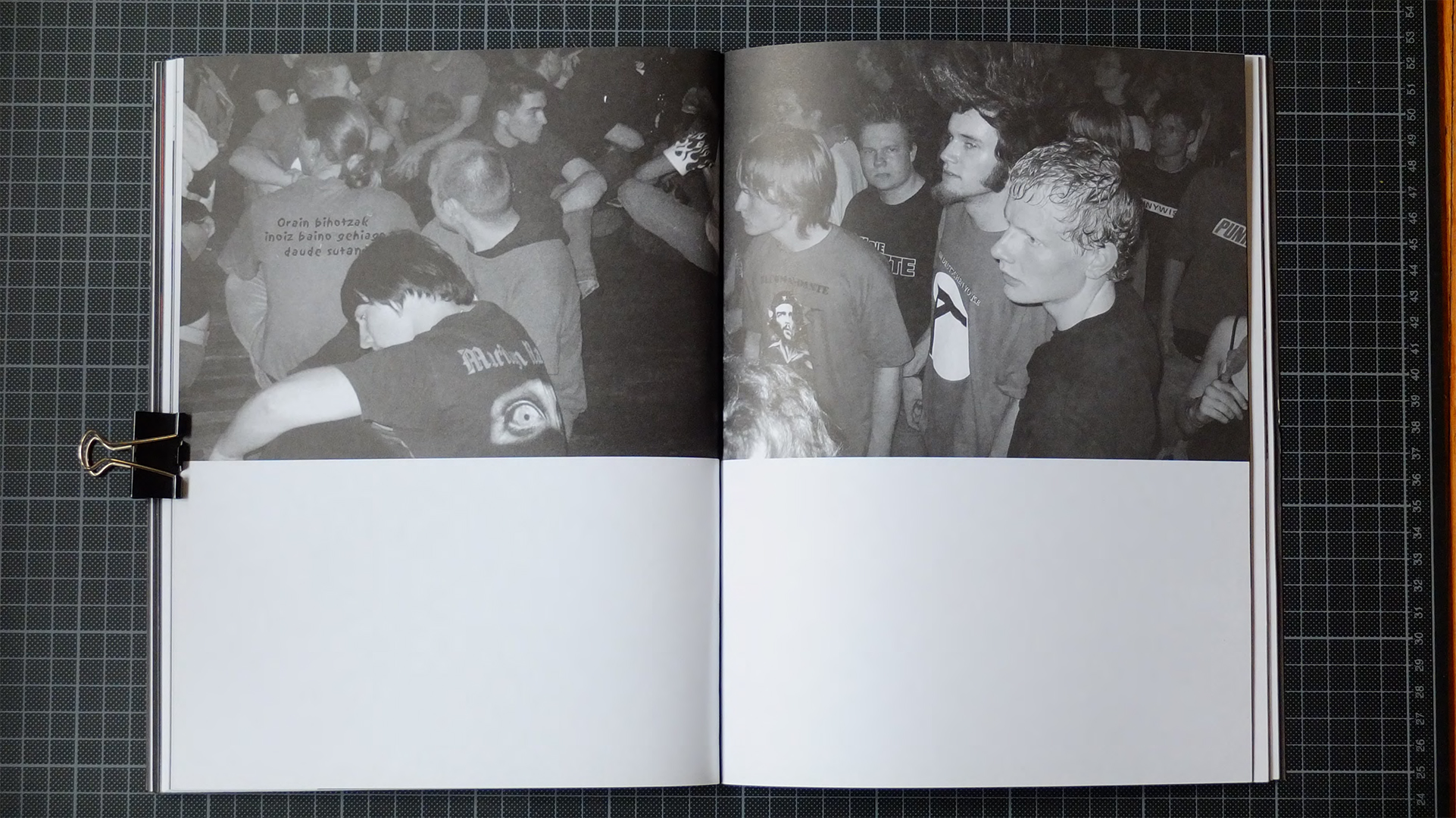

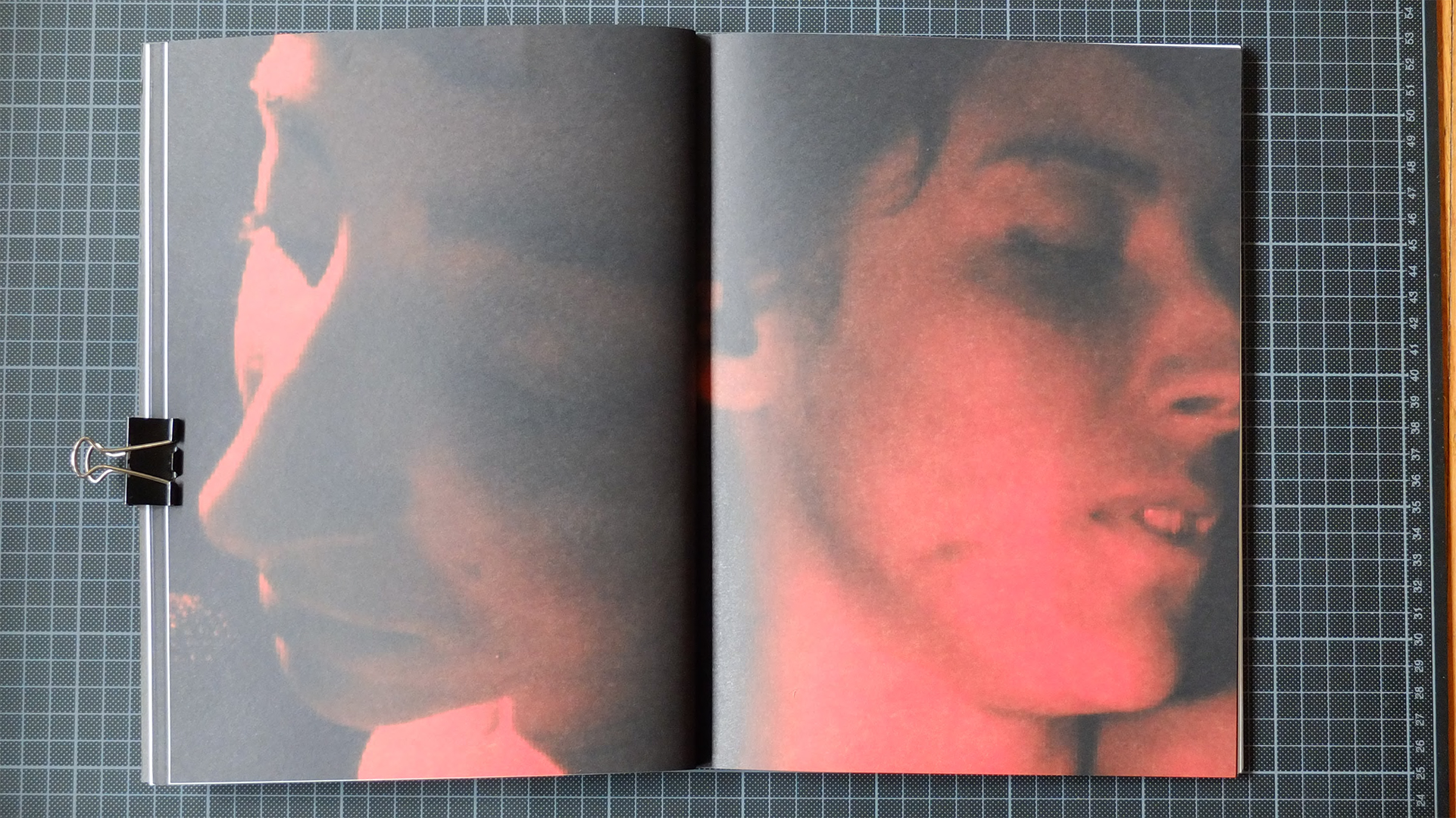

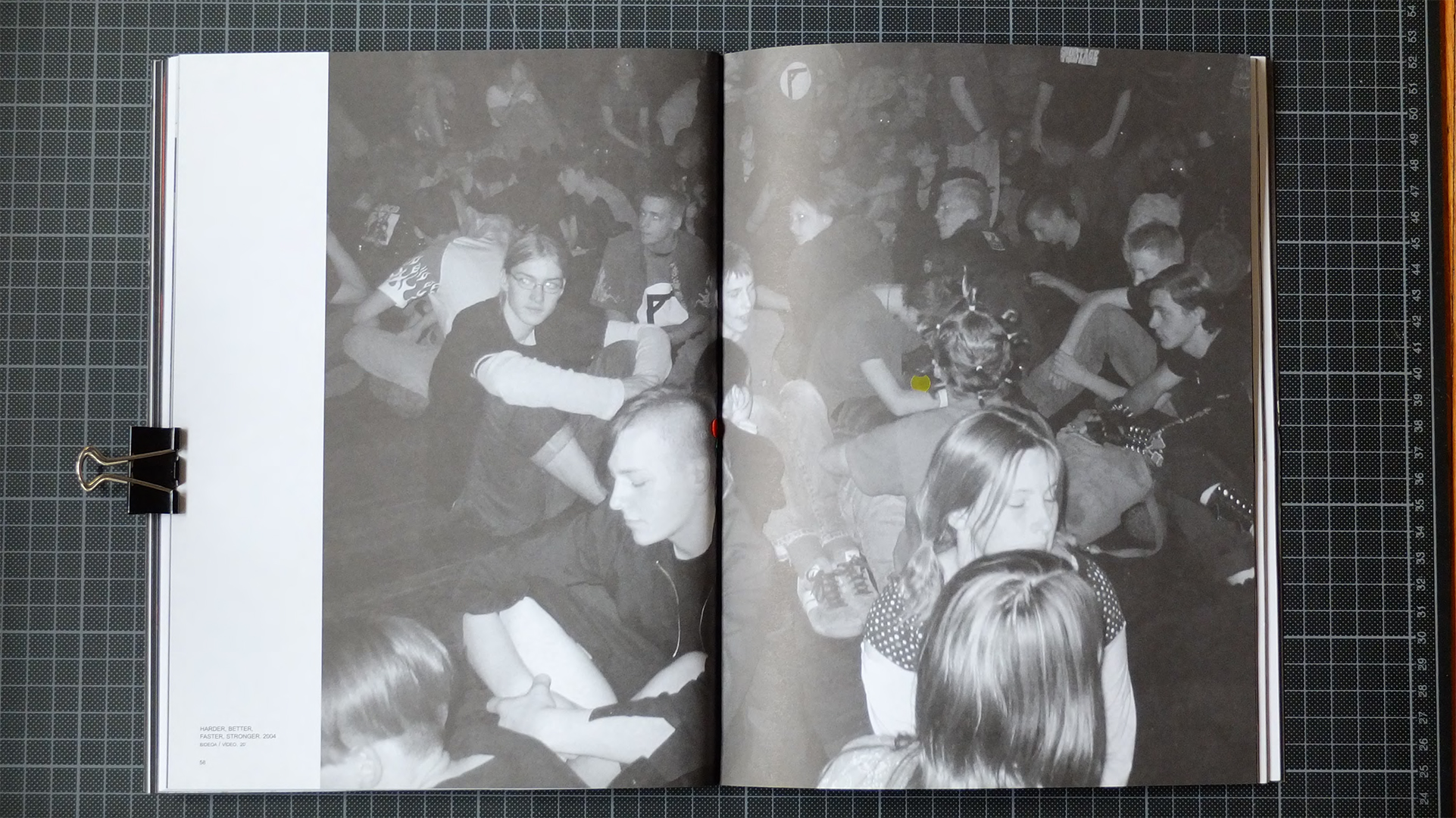

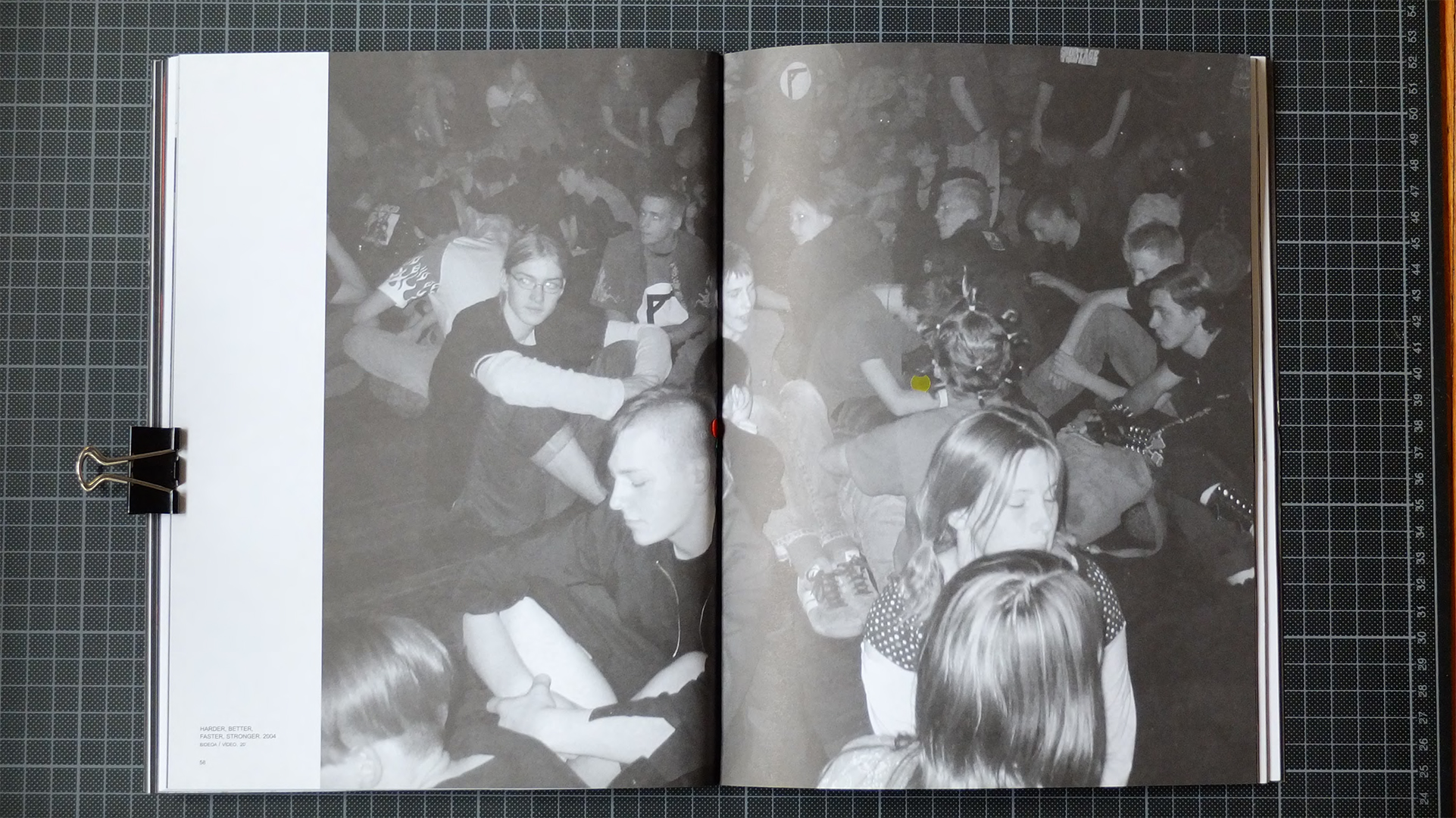

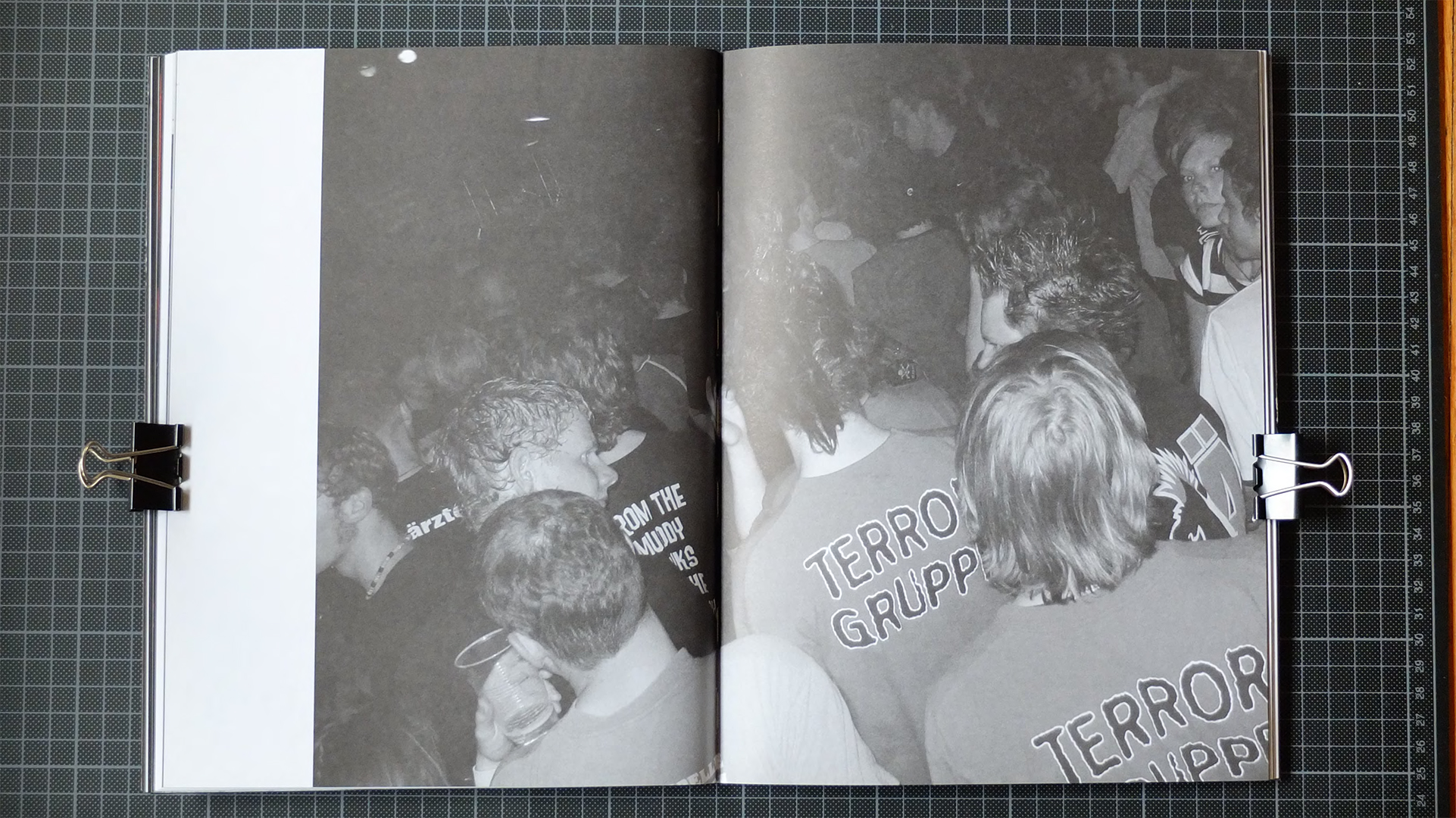

Two night scenes light up a room in the old Ziriza factory in Pasaia Trintxerpe, one of the spaces hosting Manifesta 5 in Donostia-San Sebastián. They belong to the installation entitled Harder, Faster, Better, Stronger, which premiered in the context of this European biennial.

The installation joined two images together via a soft montage, in search, perhaps, of a less affirmative, more essay-like assembly of images, as noted by Harun Farocki. Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999) was being screened in the same building, on the floor above. A compilation of moving gestures, a collage of images accounting for an atomized social choreography by the collective erosion that the Thatcher era would leave behind. In the soft montage of my memory, traces and images of both works mix in a sort of visual archeology which, in those days, appeared already in decay.

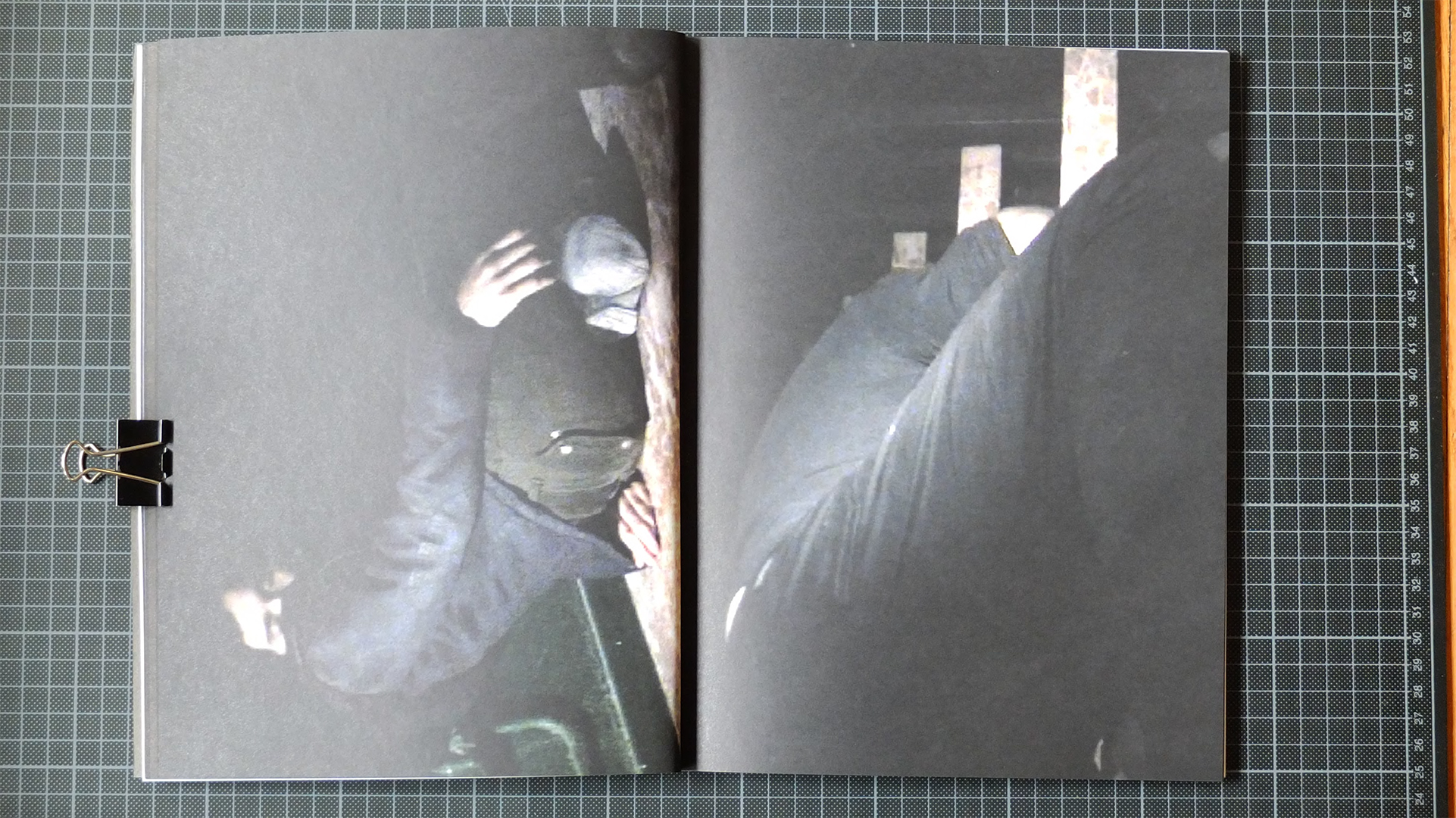

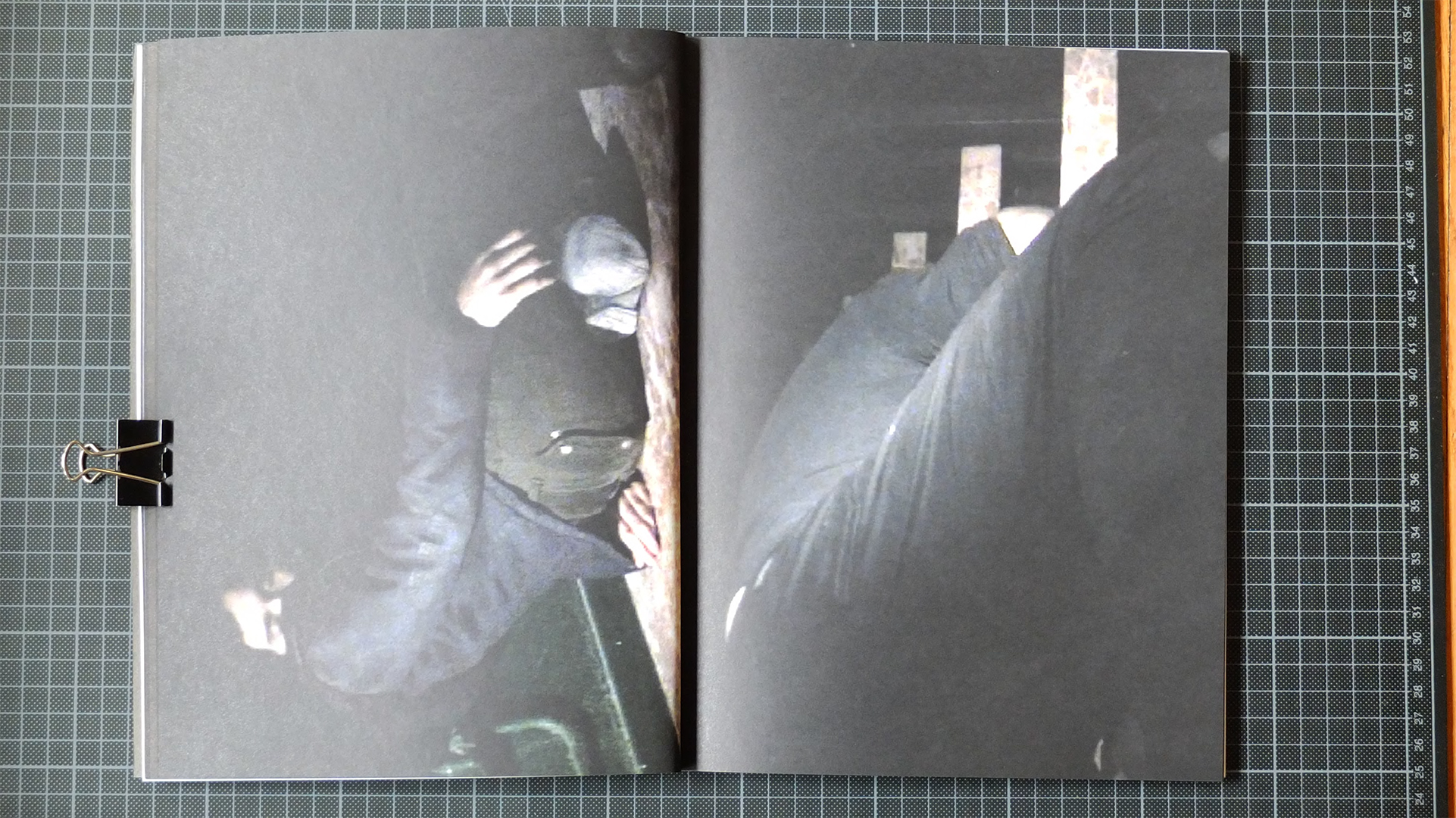

The scenes composing the single-channel version of this piece were recorded in Berlin on the night of May 1st, 2004, in the clamour of the riots that had been taking the streets of the great metropolises from the end of the 90s to the beginning of the 00s. These protests were not only a way to raise awareness of the rejection of globalisation, but also a symptom of the progressive deterritorialization of power and the masses.

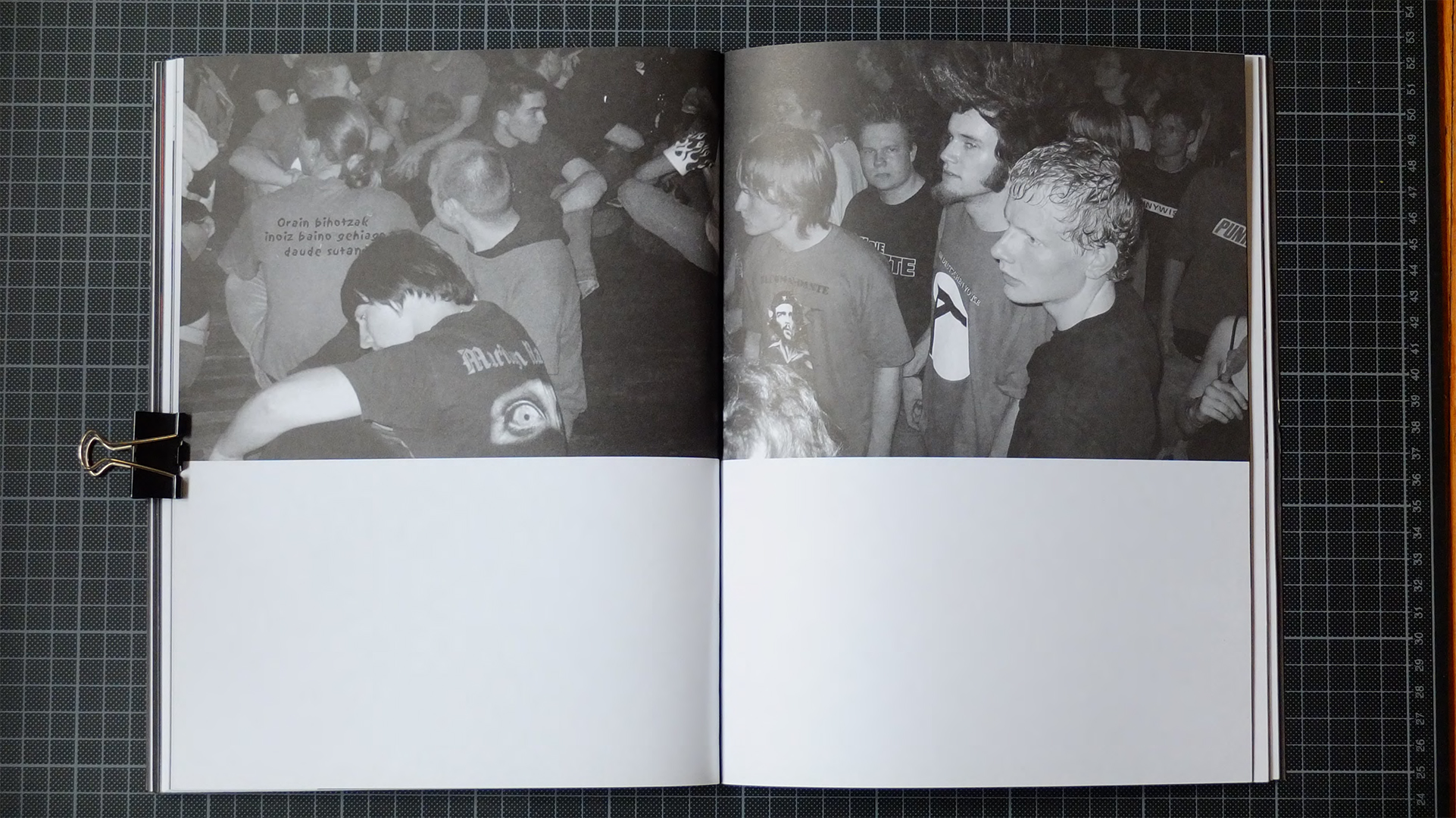

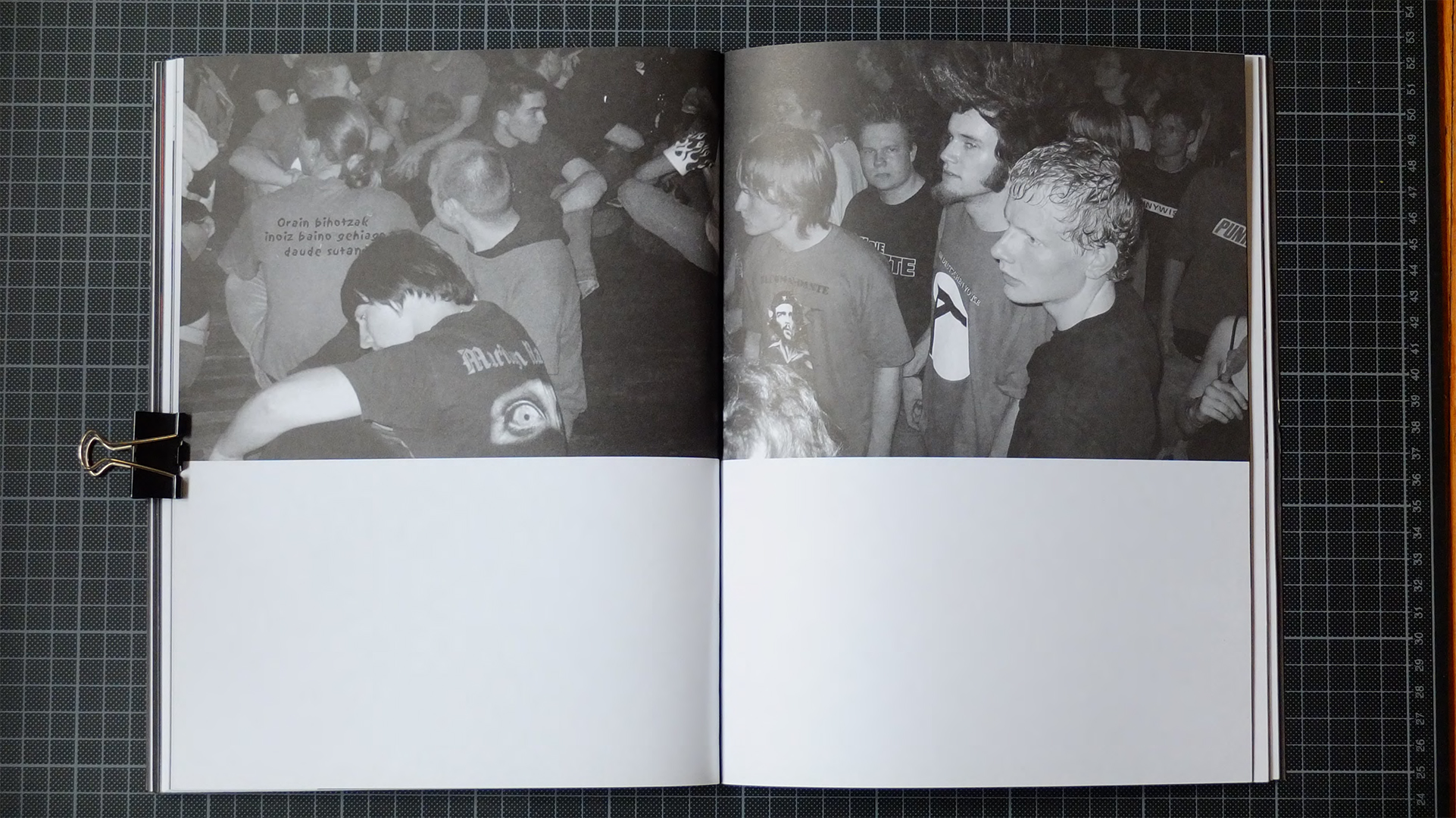

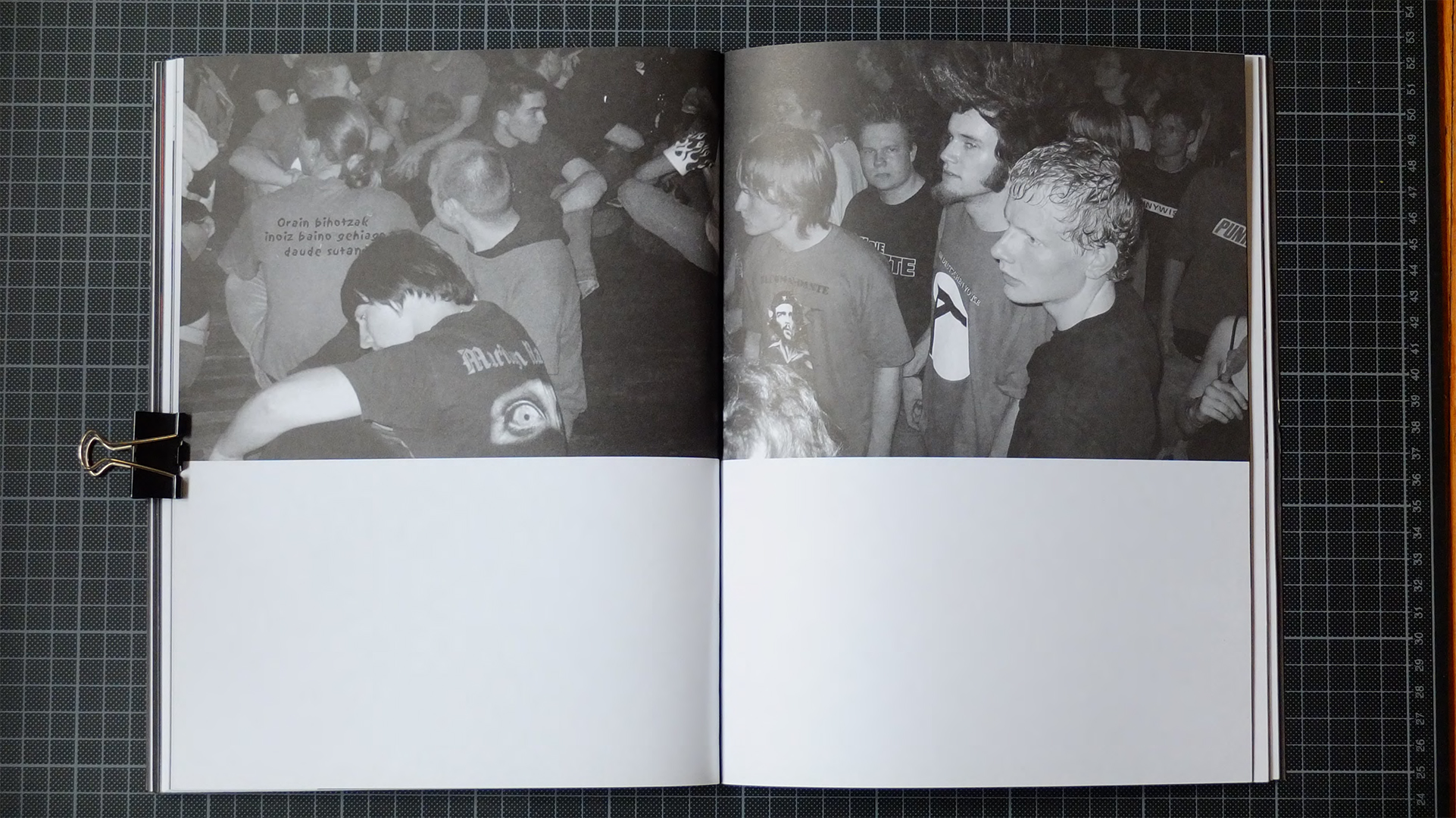

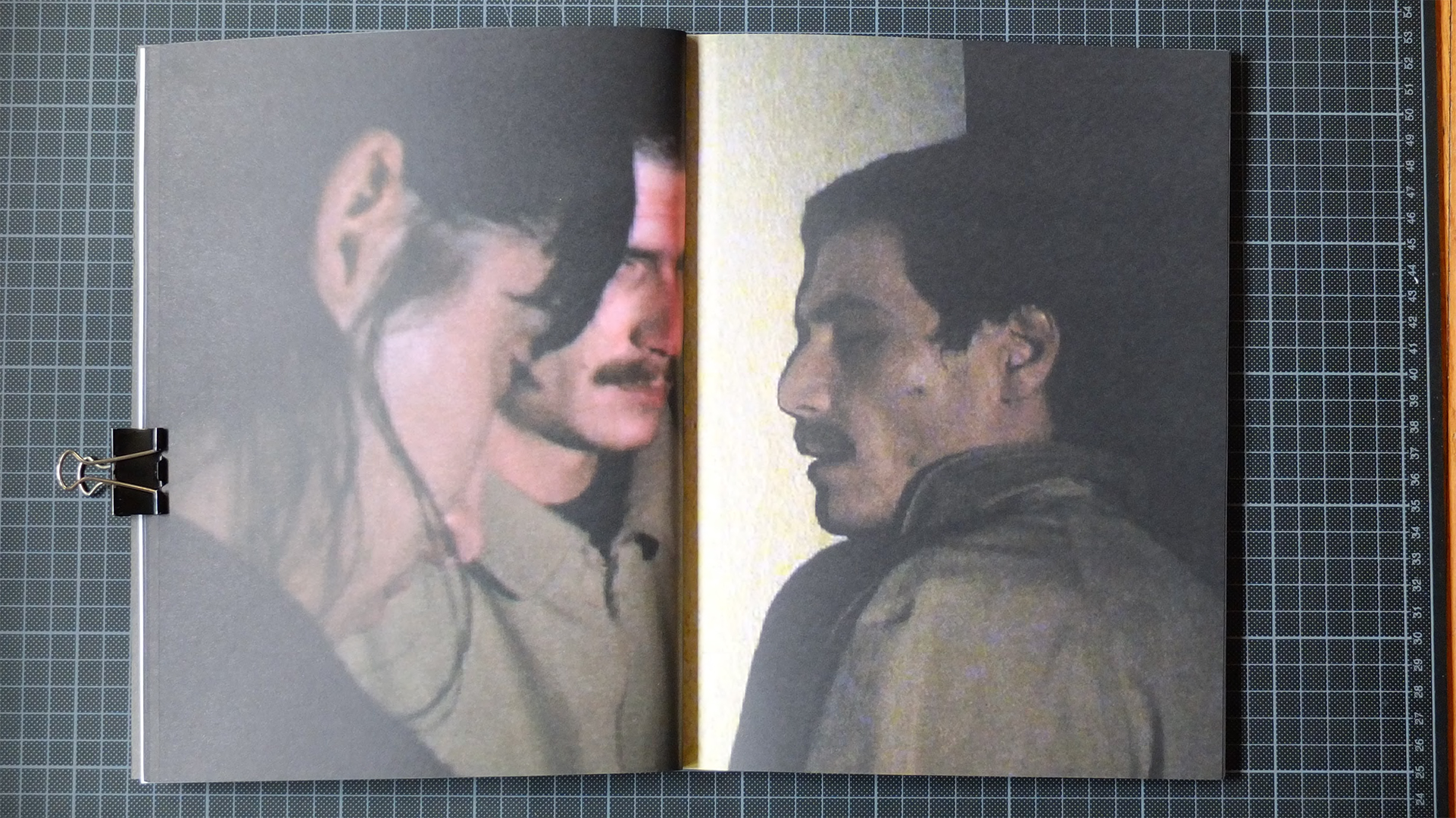

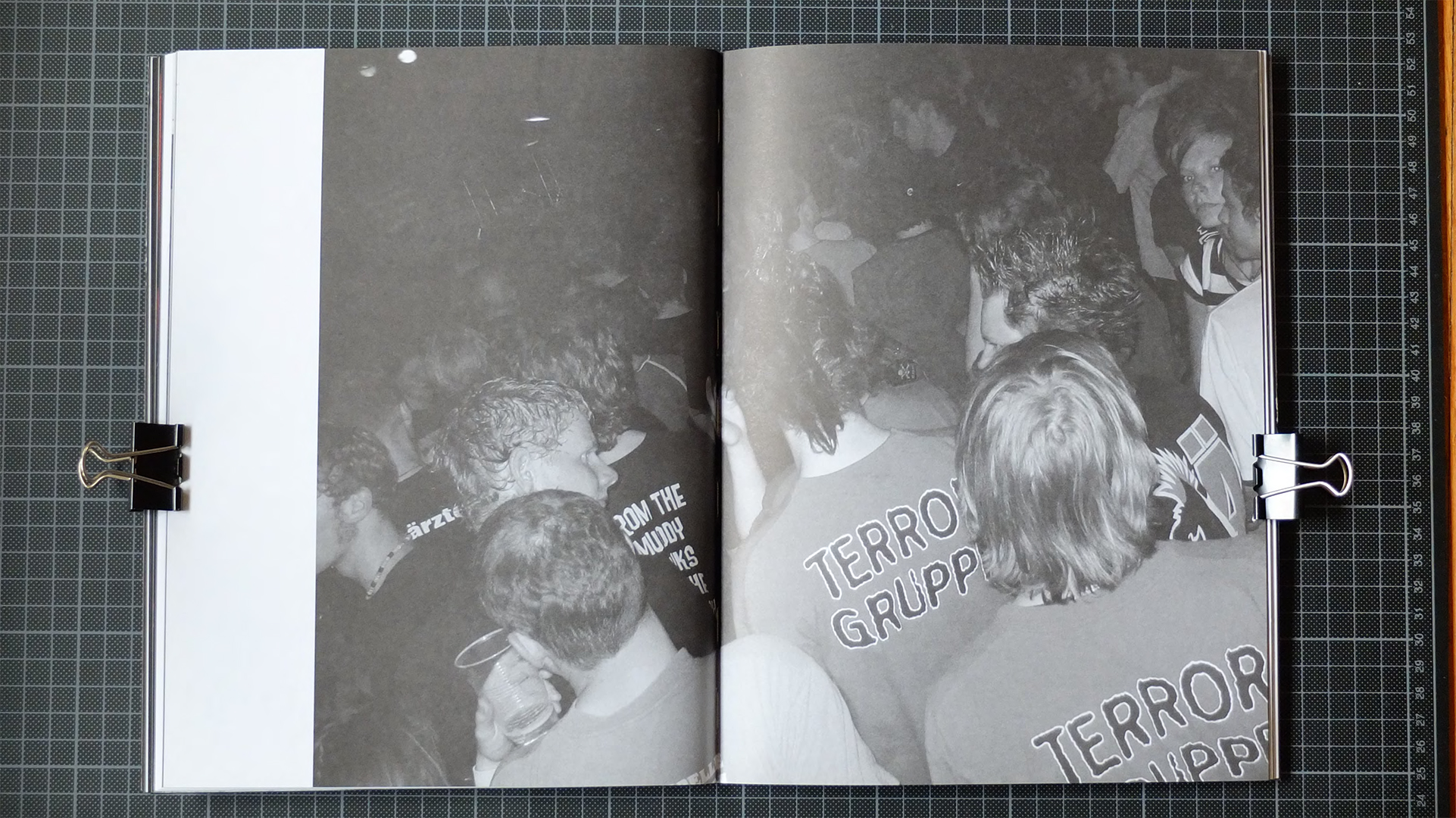

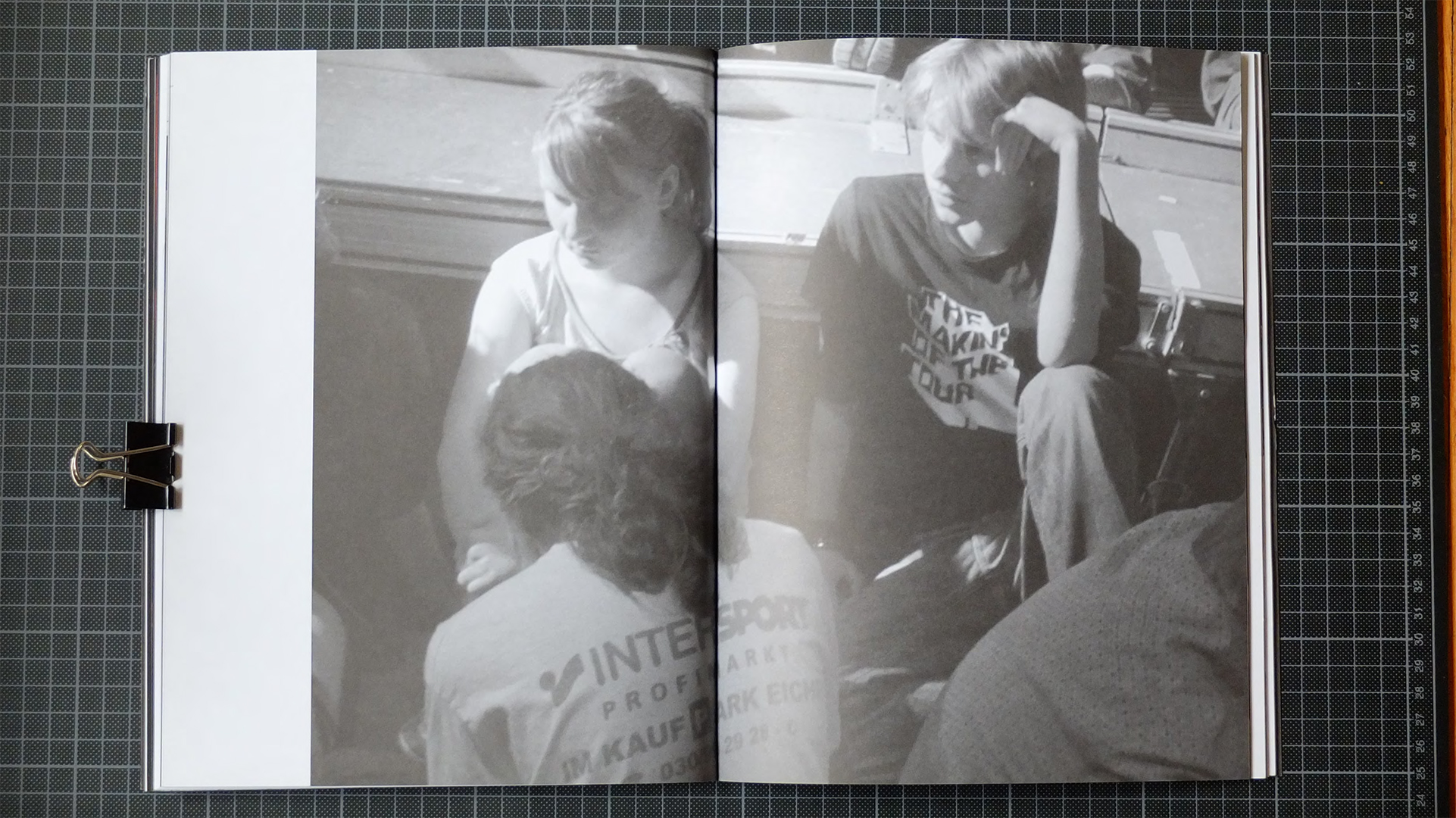

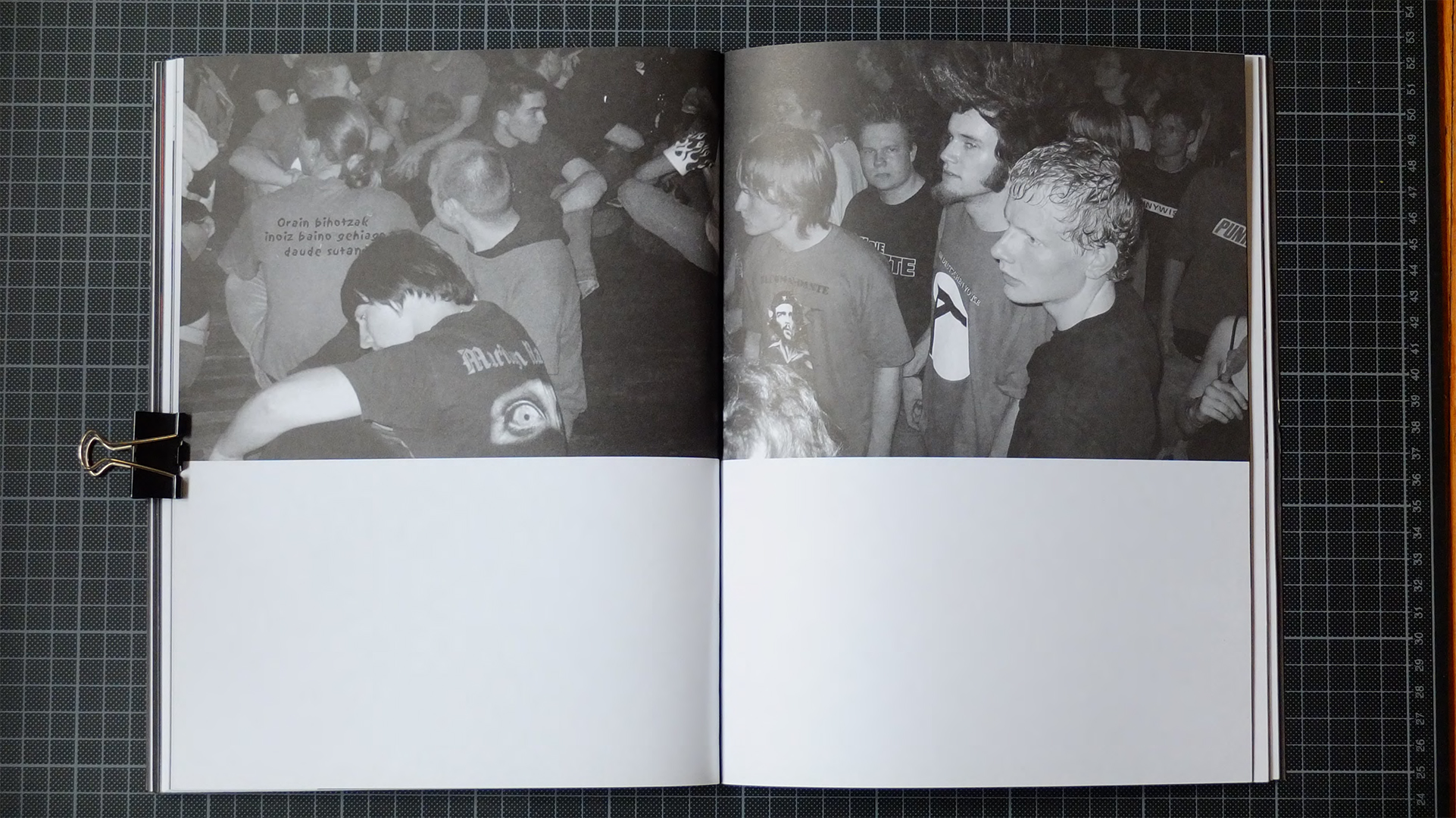

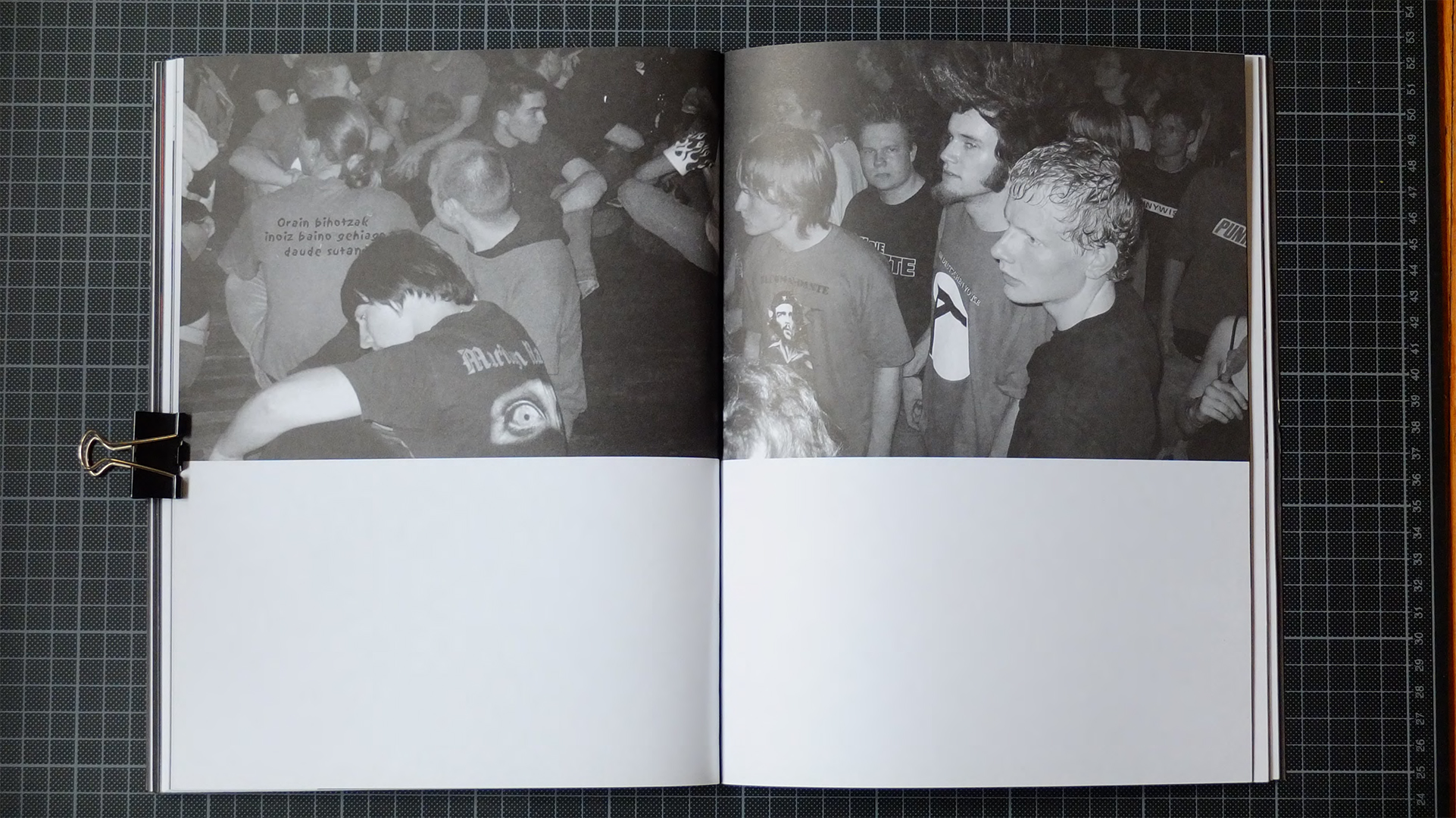

In one of the scenes, a mass of bodies sits and waits for the start of a concert of the punk band Terrorgruppe. The camera has been placed at the back before the concert, in centre stage and somewhat elevated. Once the concert begins, the camera is right at the front, also centred. One of the microphones, installed before the appearance of the band, indicates the central position of the takes. The room fills up, the camera remains static, capturing the lights bathing the gathering of bodies. In the other scene, we can see a field at night, with the remains of plastic cups and other rubbish, as well as police officers and a few arrests, small groups of people leaving. As the footage continues, we see the dancing mass, mostly male, as if it were its inherent form, a complete entity, moving in perfect sync, especially when the sound and the image match. When the sound is off, the distance increases and the illusion of this uncracked reality disappears. The raw image makes us more aware of the device structuring the scene. In parallel, the field keeps emptying out as the night draws on and police presence grows.

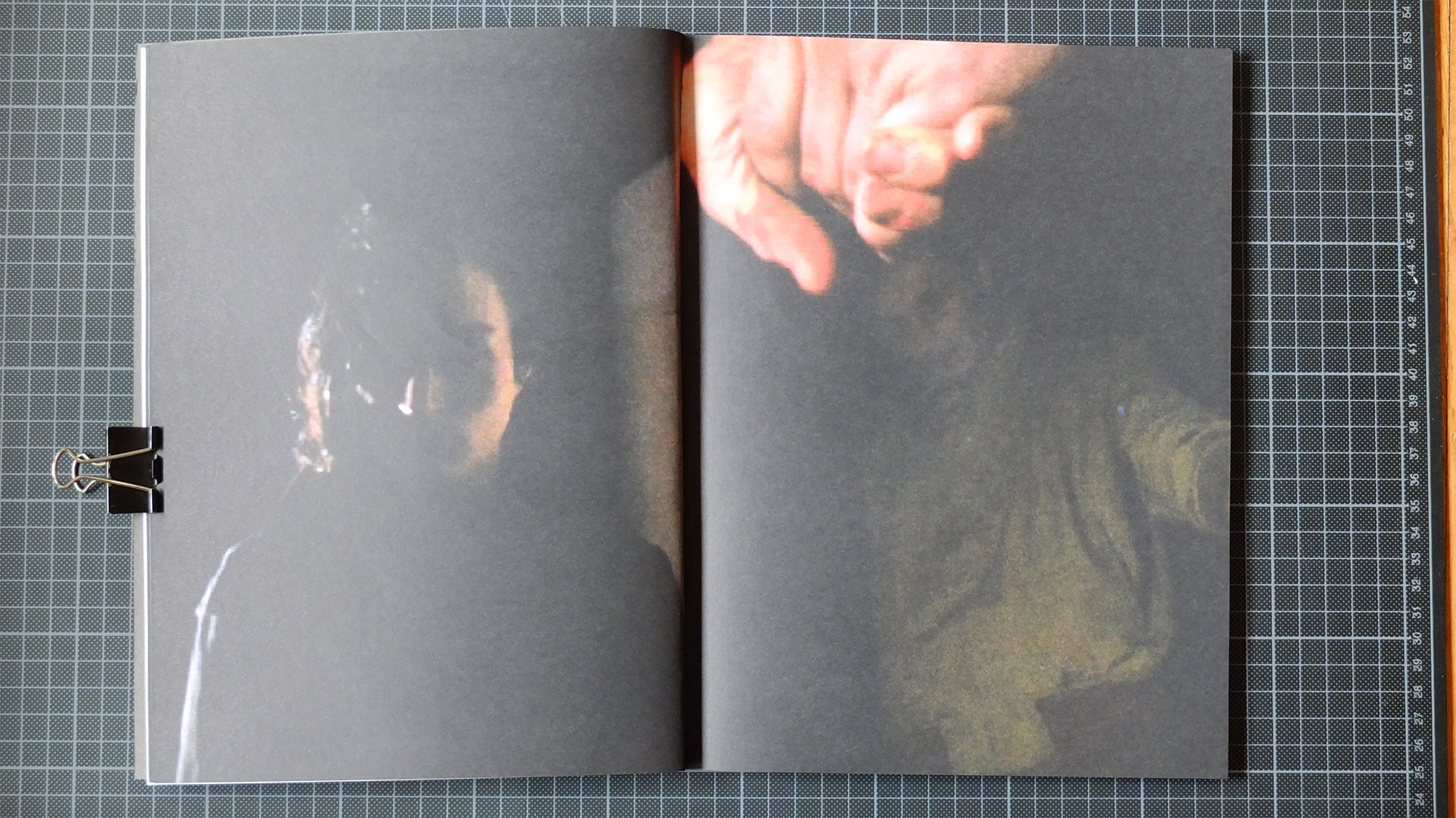

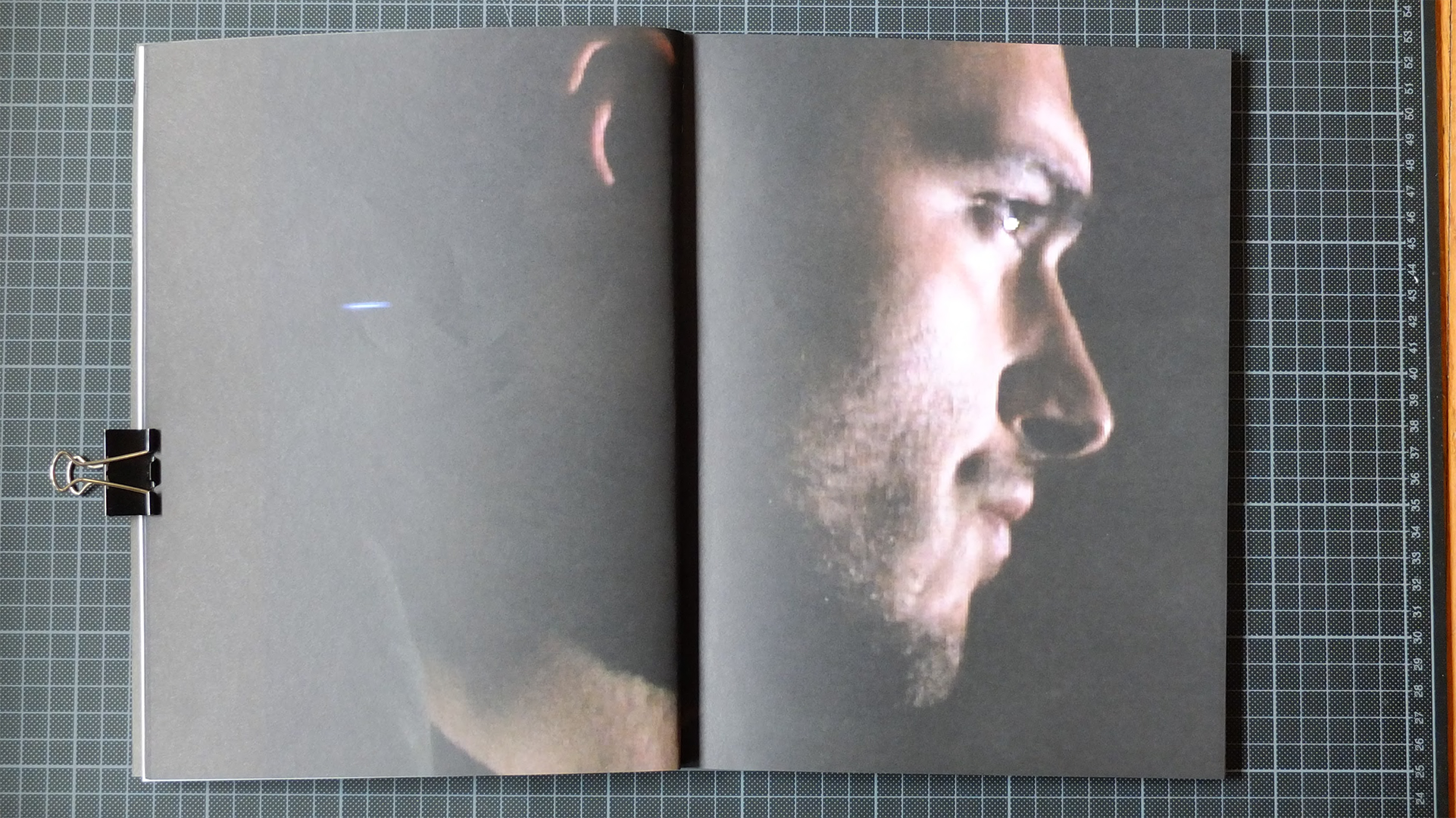

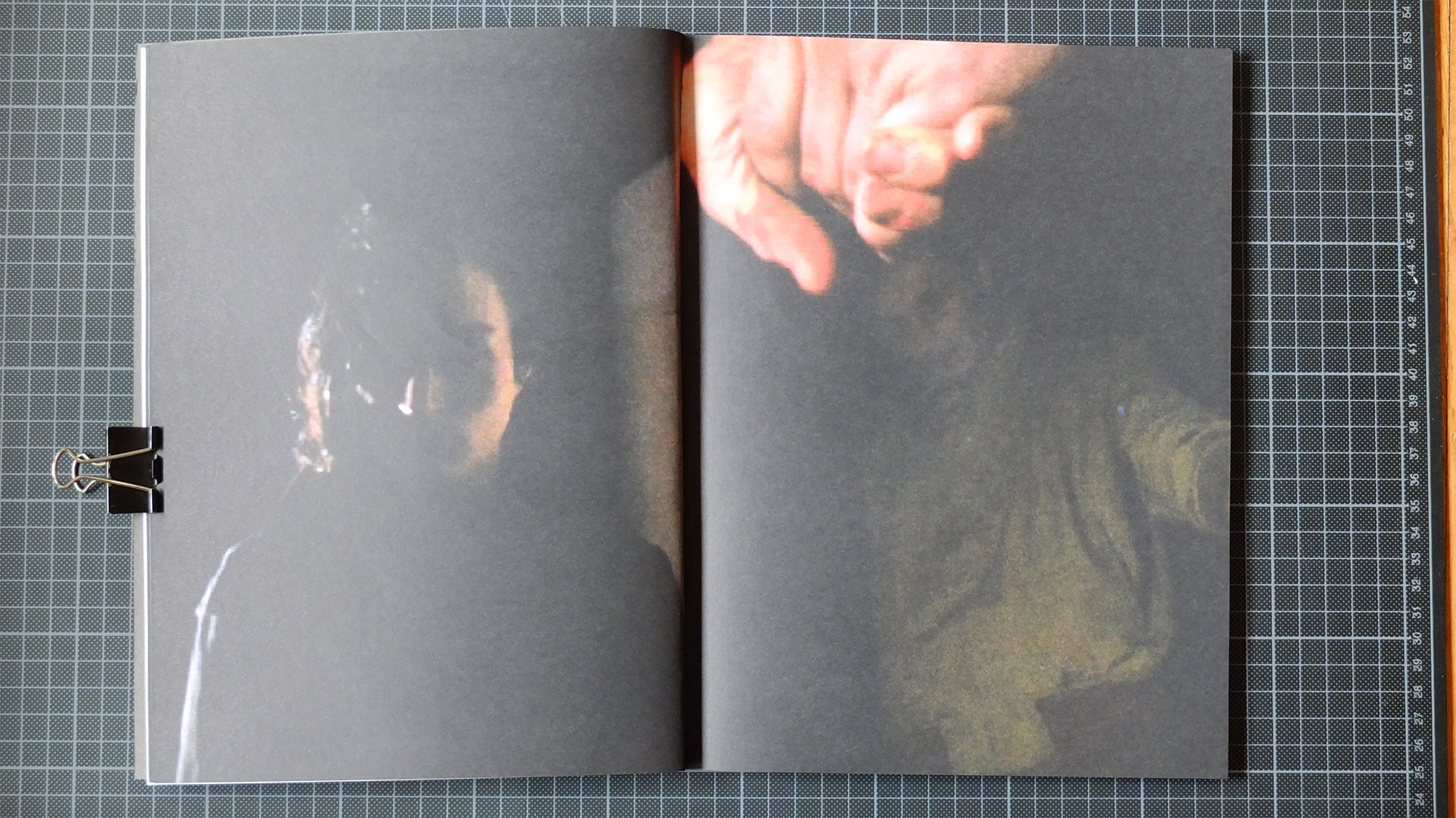

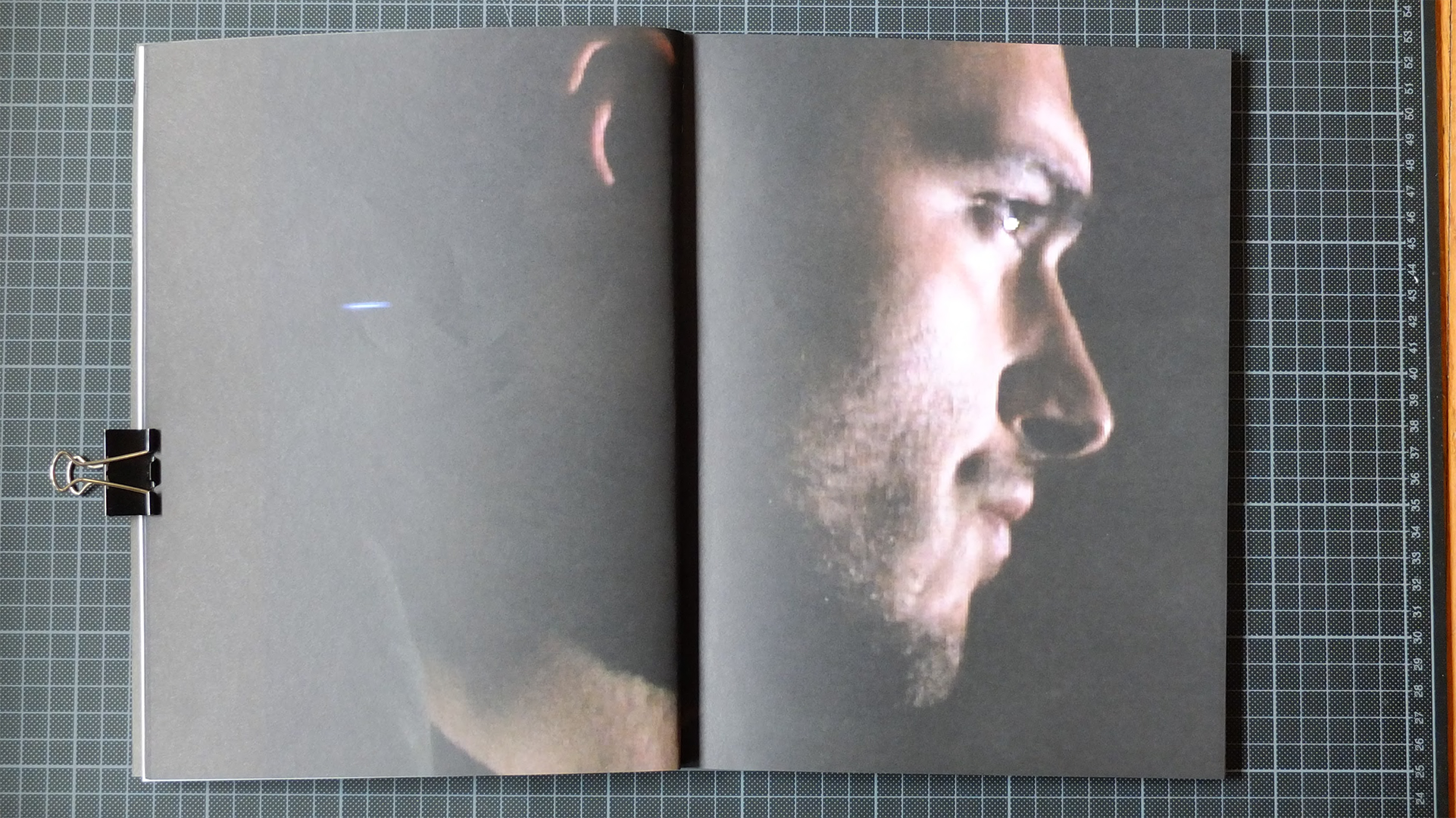

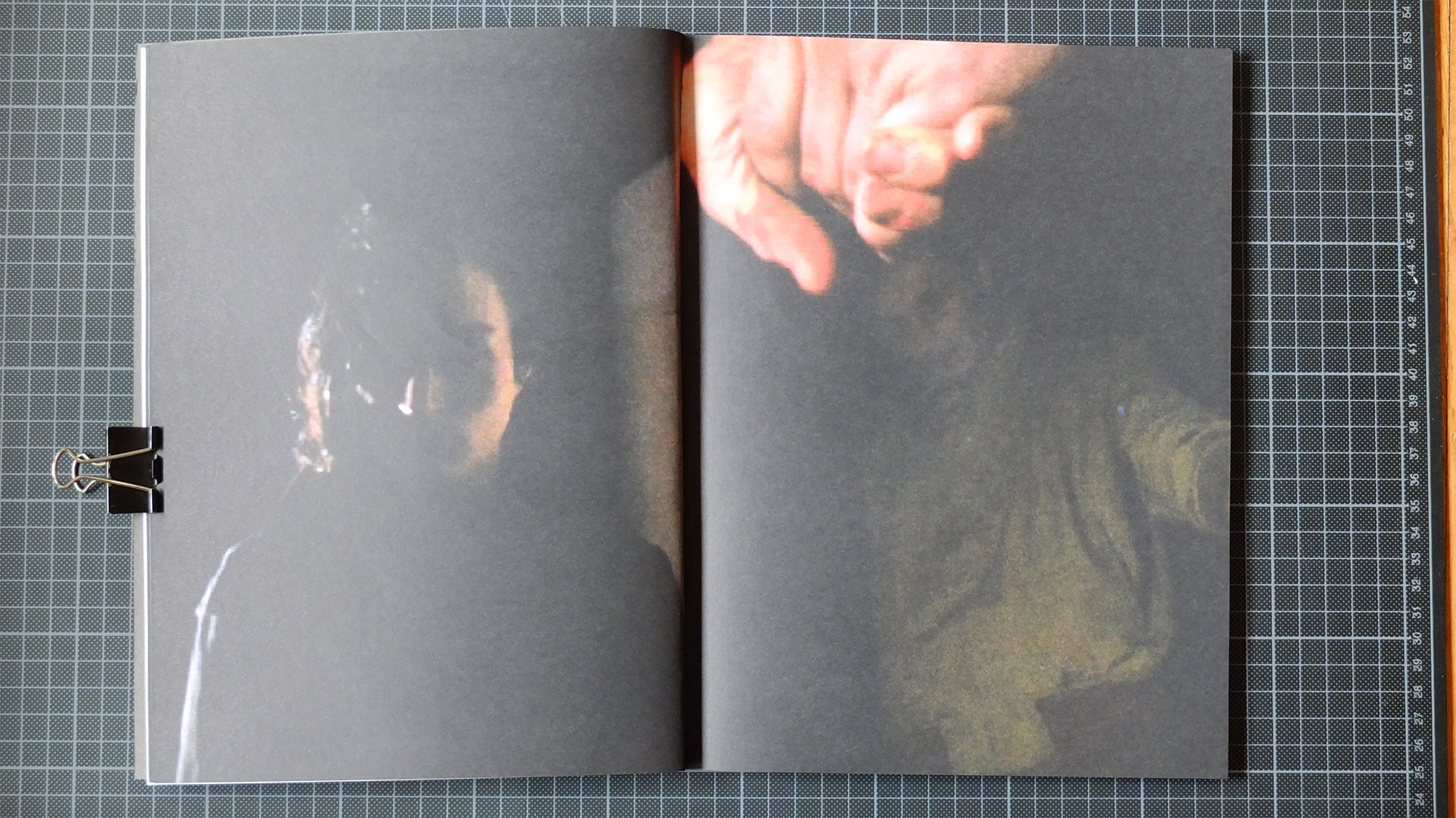

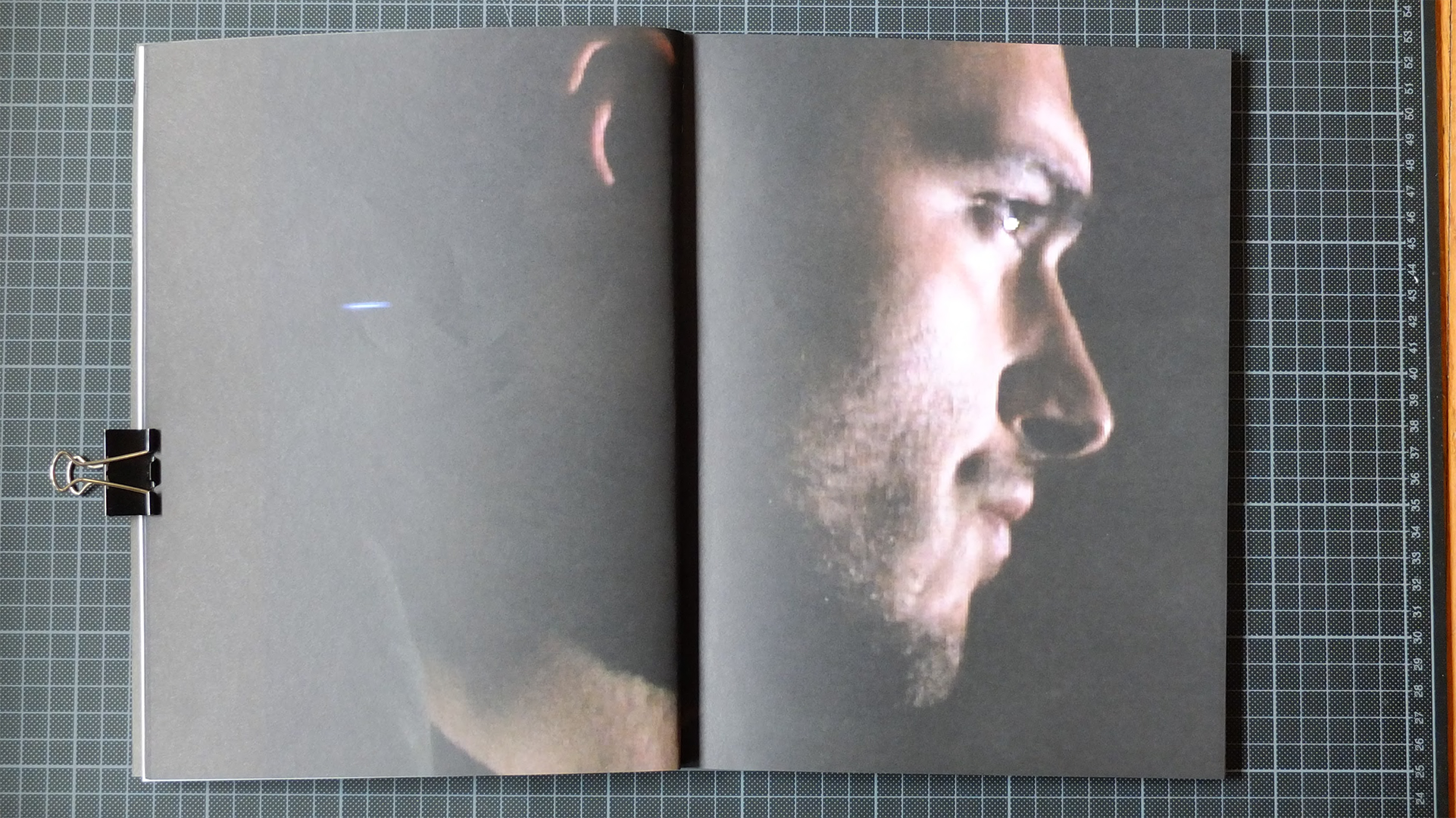

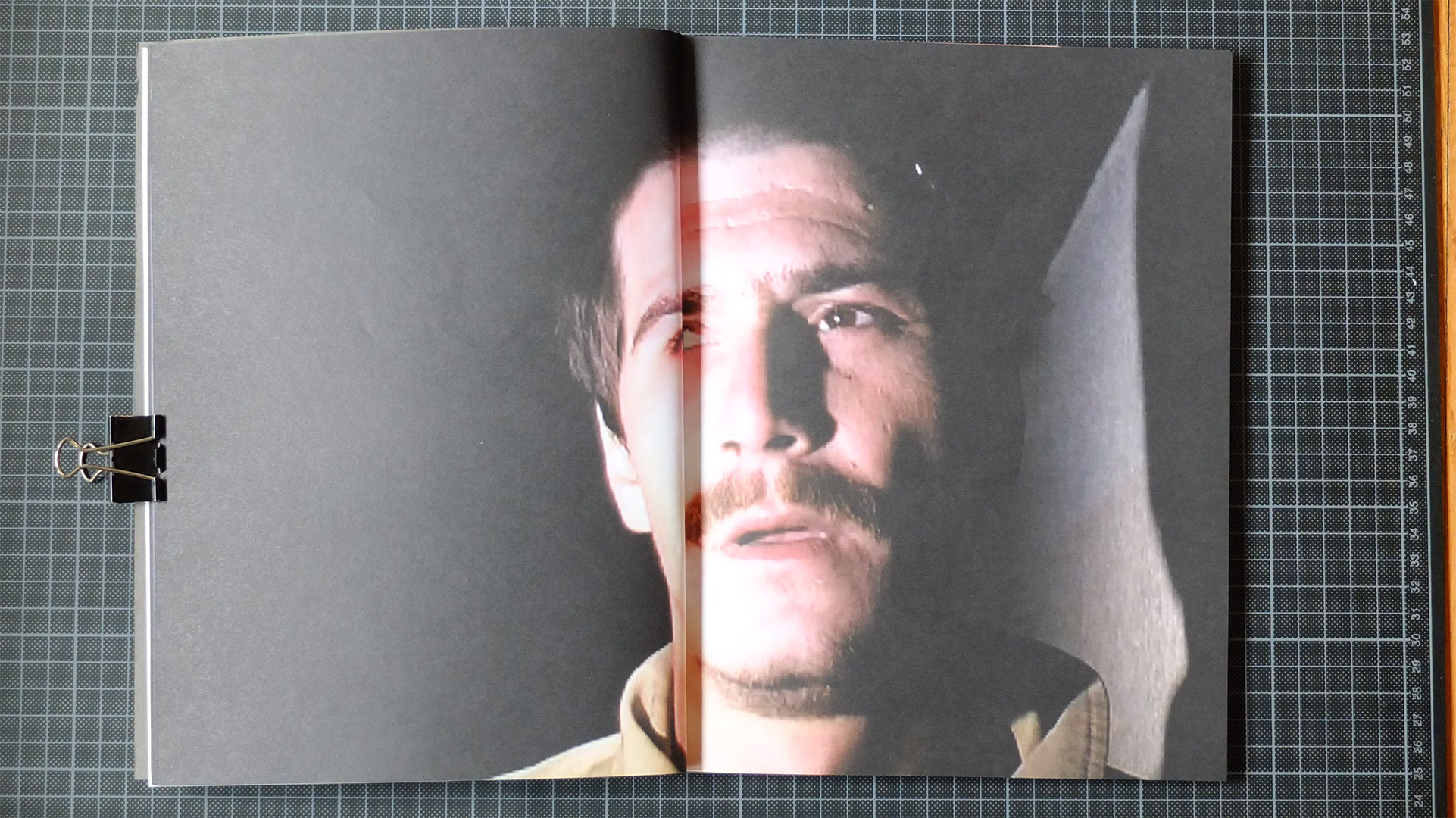

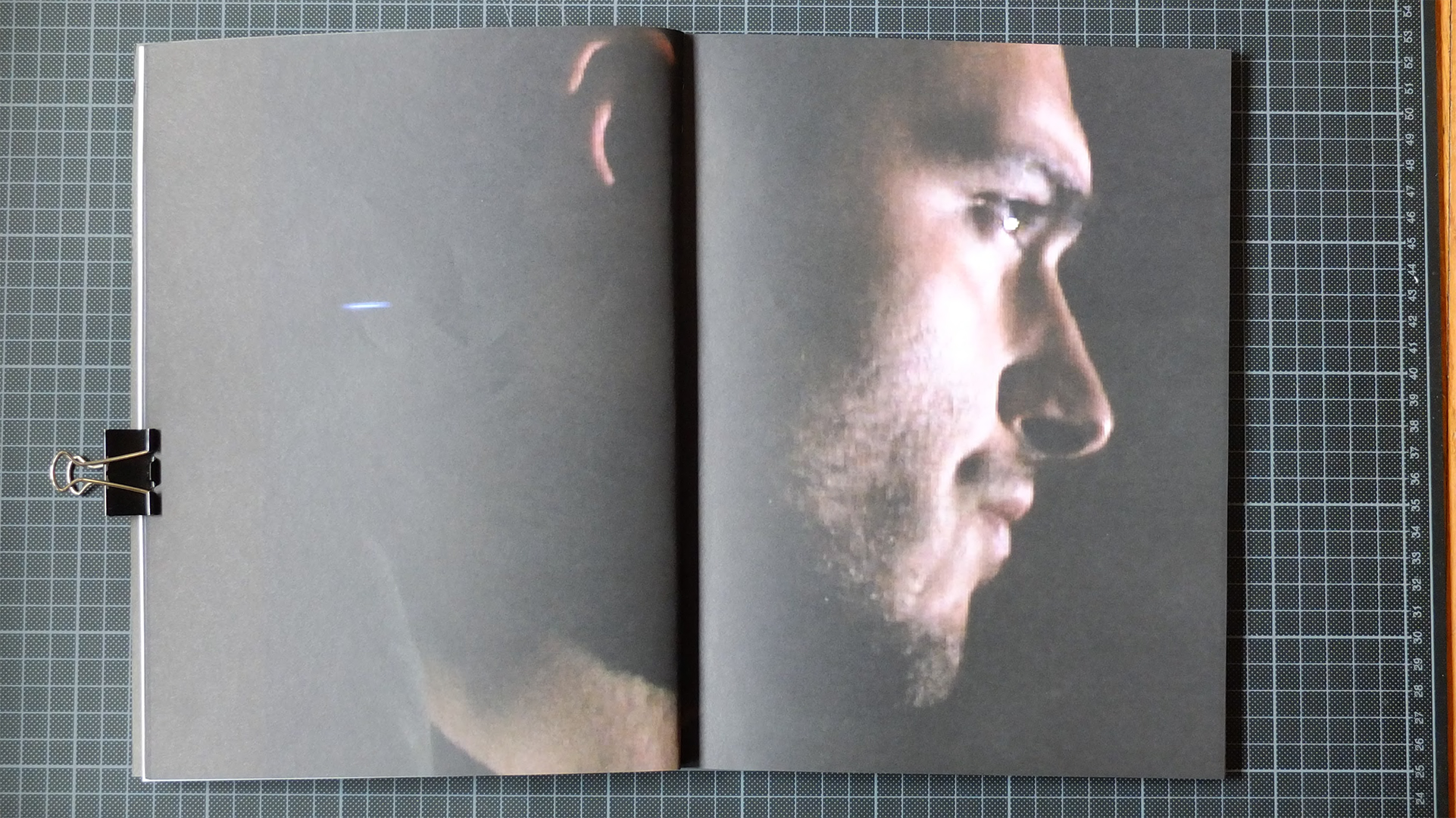

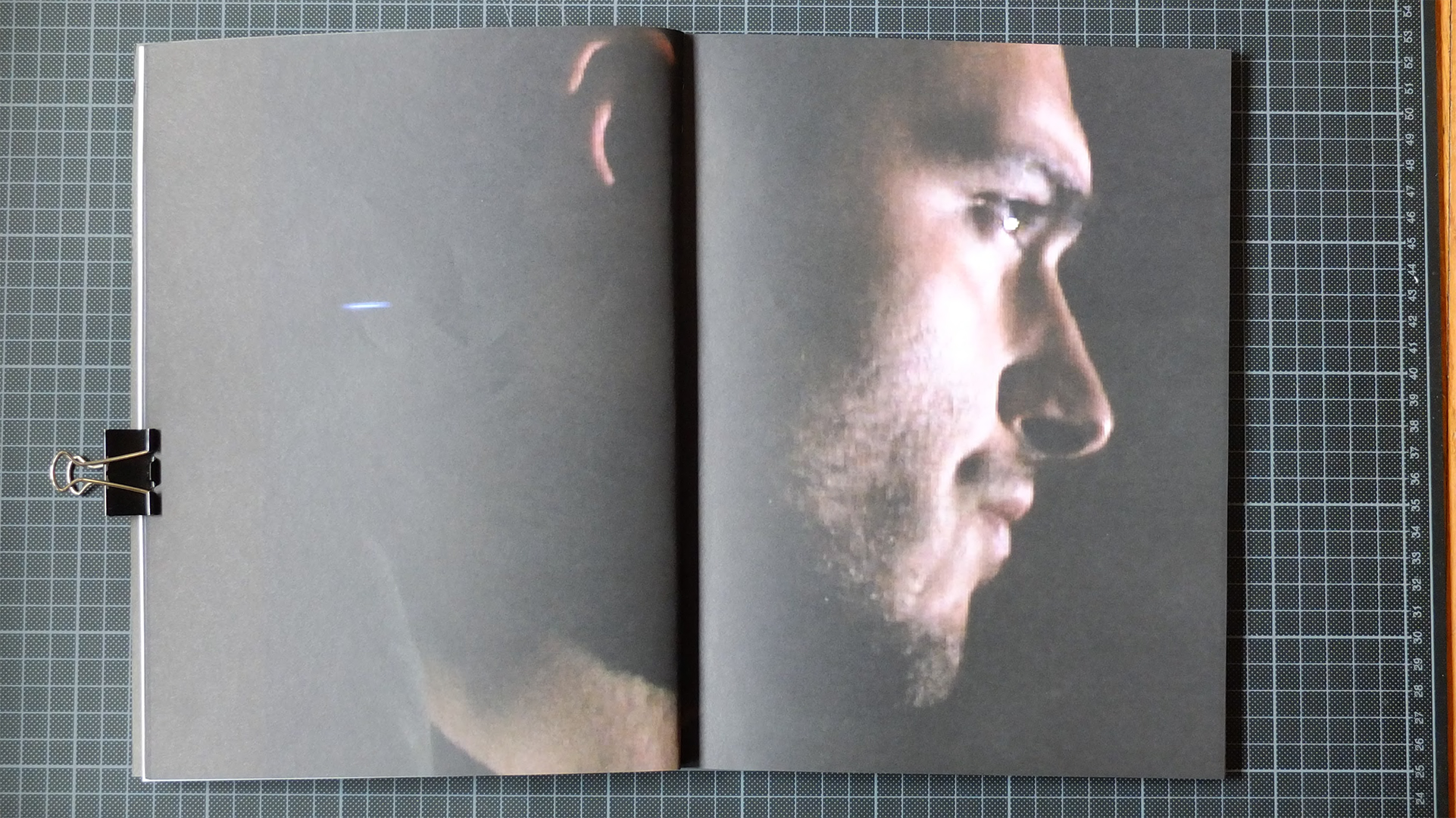

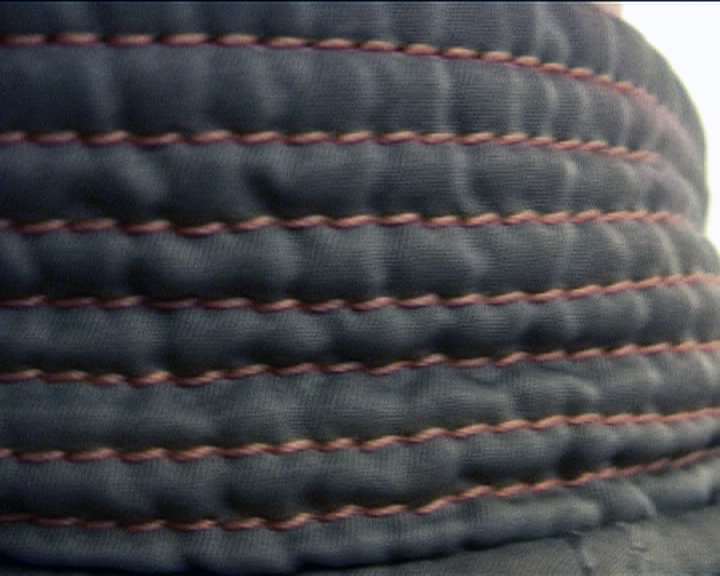

In the context of this night-time filming, a collection of images came up, which were taken as random portraits prior to the show. The camera infiltrated the crowd in order to access a more fragmented gaze. The resulting close-ups break from the notion of mass to pause at the style details on which this generation constructs its identity. These images were used in the cover of the book Only Kids Love Other Kids and the poster Orain bihotzak inoiz baino gehiago daude sutan for the exhibition Beste Bat! (a retrospective account of the Basque Radical Rock Movement) (2004) curated by Miren Jaio and Fito Rodríguez at Sala Rekalde (Bilbao).

Related bibliography

Miren Jaio. “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger: Iñaki Garmendia en Manifesta 5”, Mugalari, Gara, no. 276, 03/07/2004.

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

KATAKRAK: Iñaki Garmendia. [Exh. cat.]. Barcelona: Barcelona City Council, Institut de Cultura, 2011.

Catalogue of solo exhibition at Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, titled Katakrak (14/07-02/10/2011) including “Metraje”, a text by Peio Aguirre, in Spanish, Catalan and English. The text basis its analysis of the artists work on videos such as S.T. (Orbea) (Orduña) (2007), Bolueta (2011), Kolpez Kolpe (2003), Harder, Faster, Better, Stronger (2004), and series such as Txitxarro (2000). With black and white images and brief artist bio.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

18’ 53’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

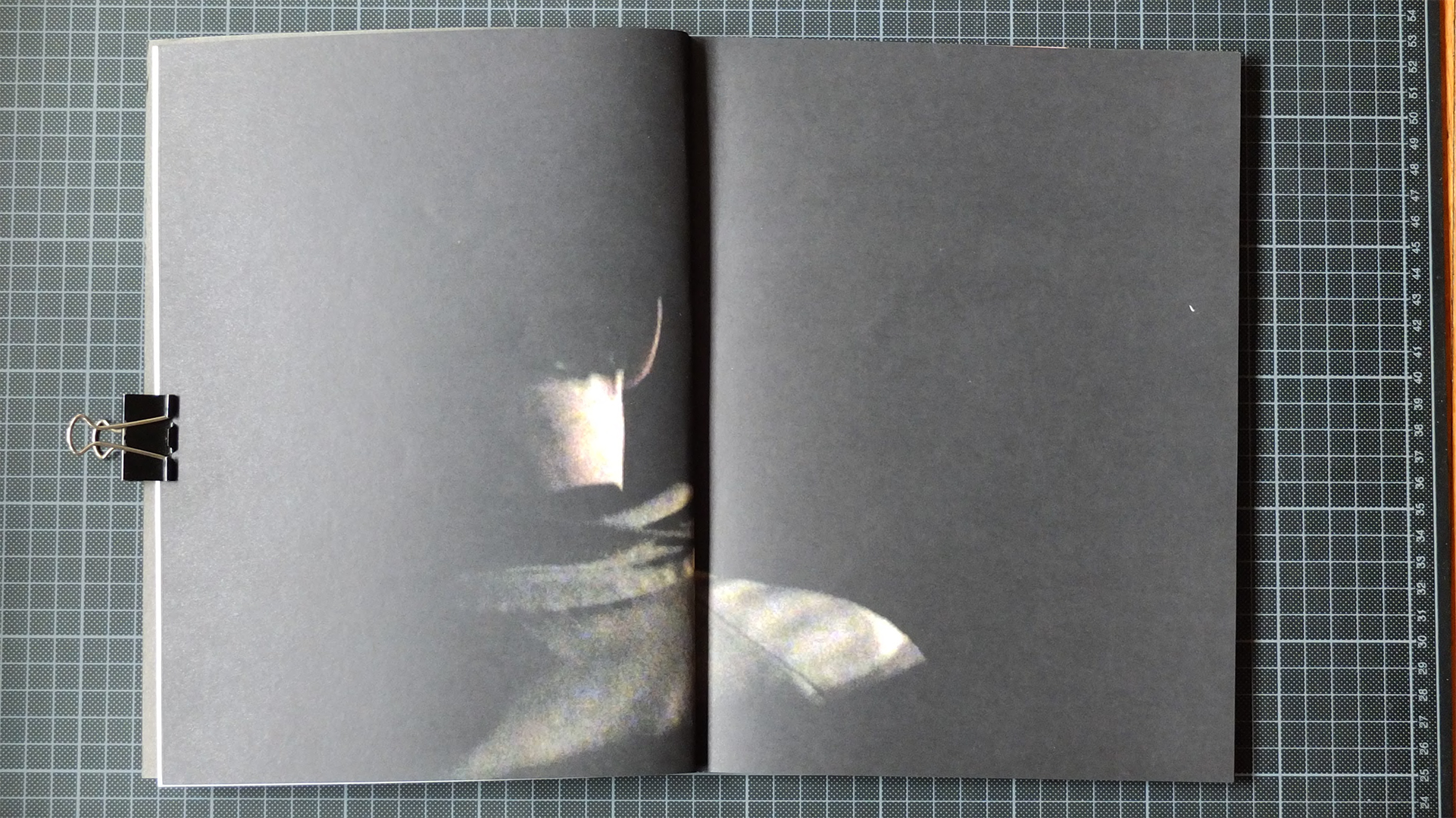

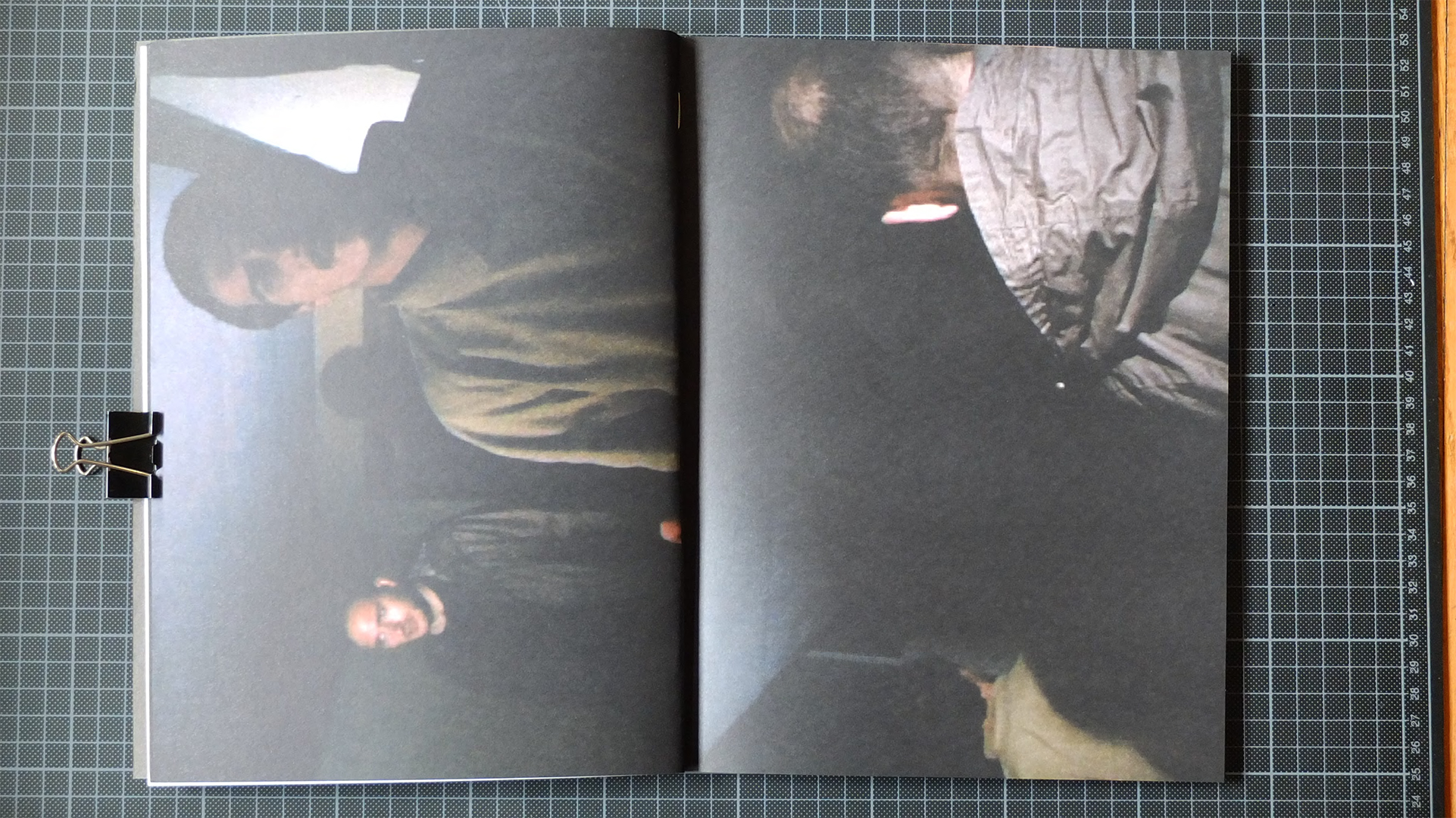

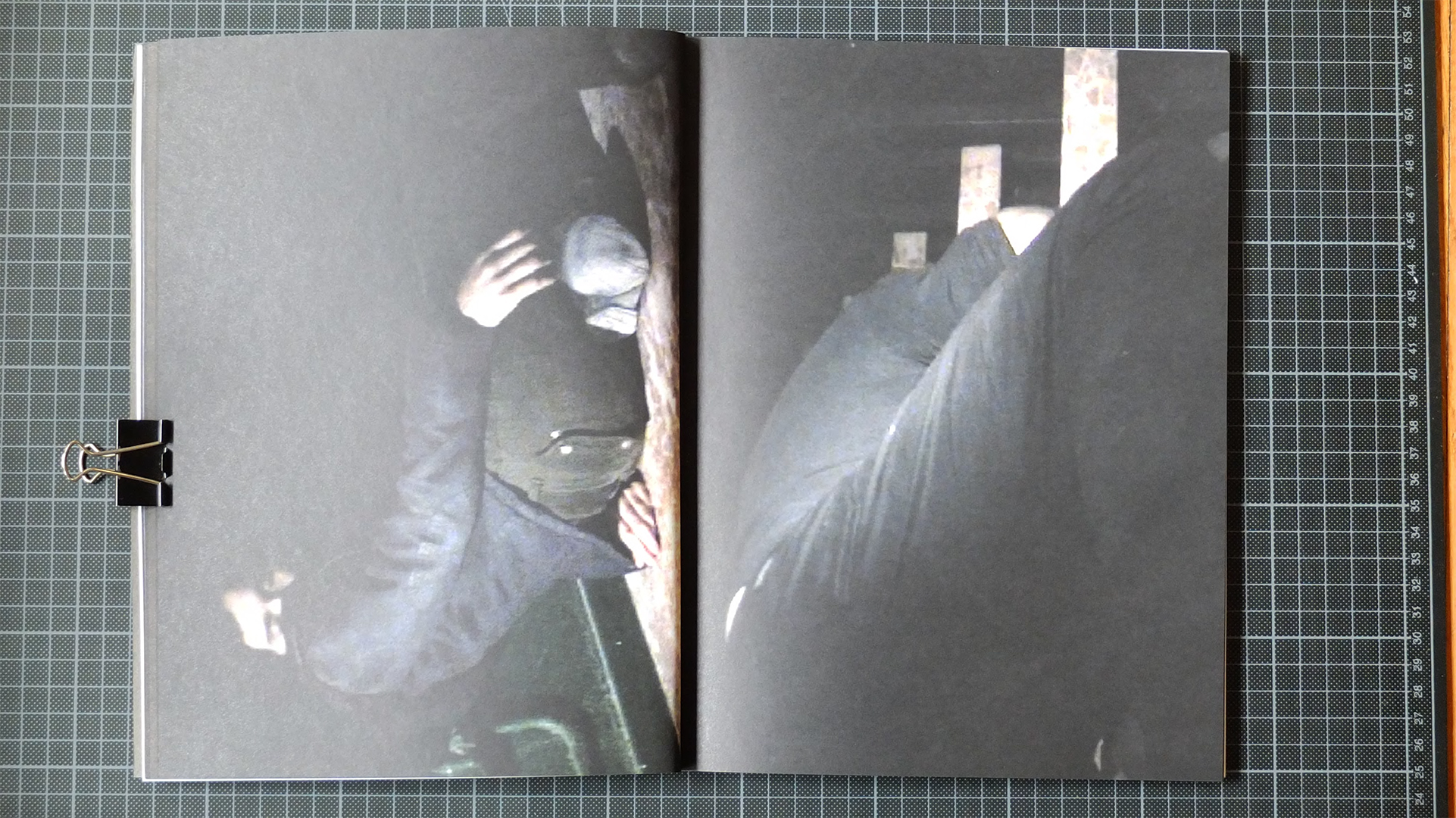

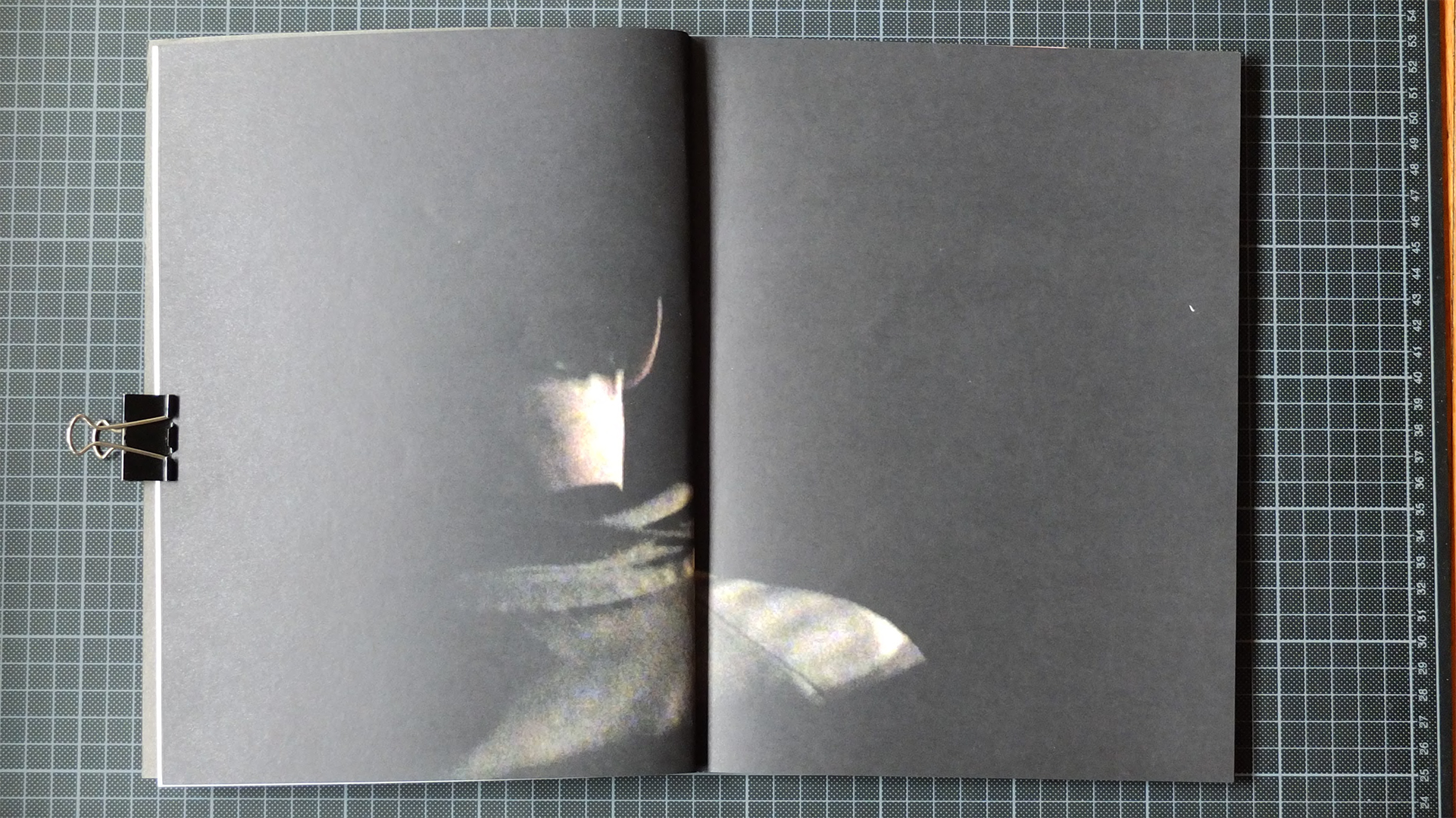

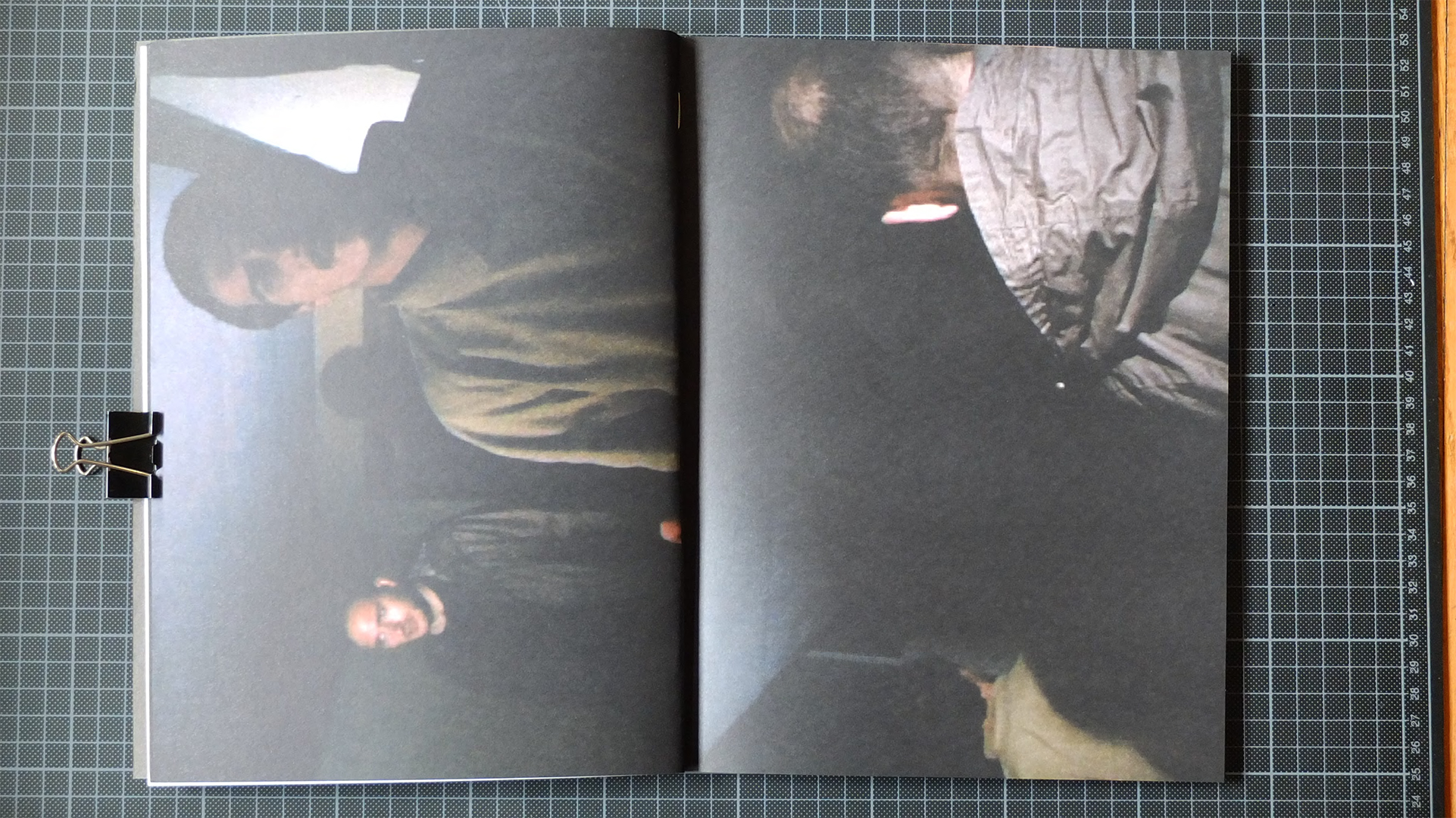

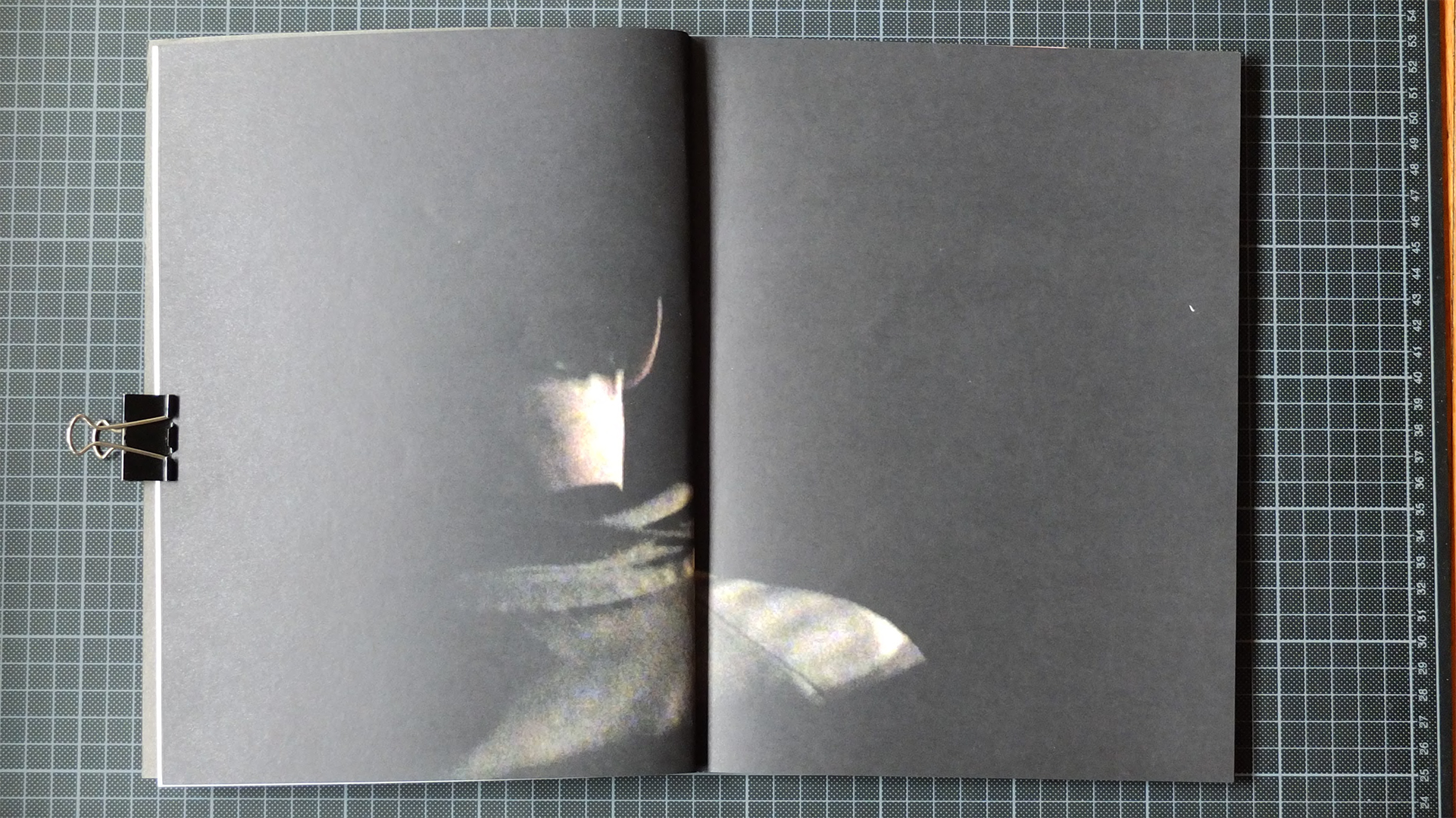

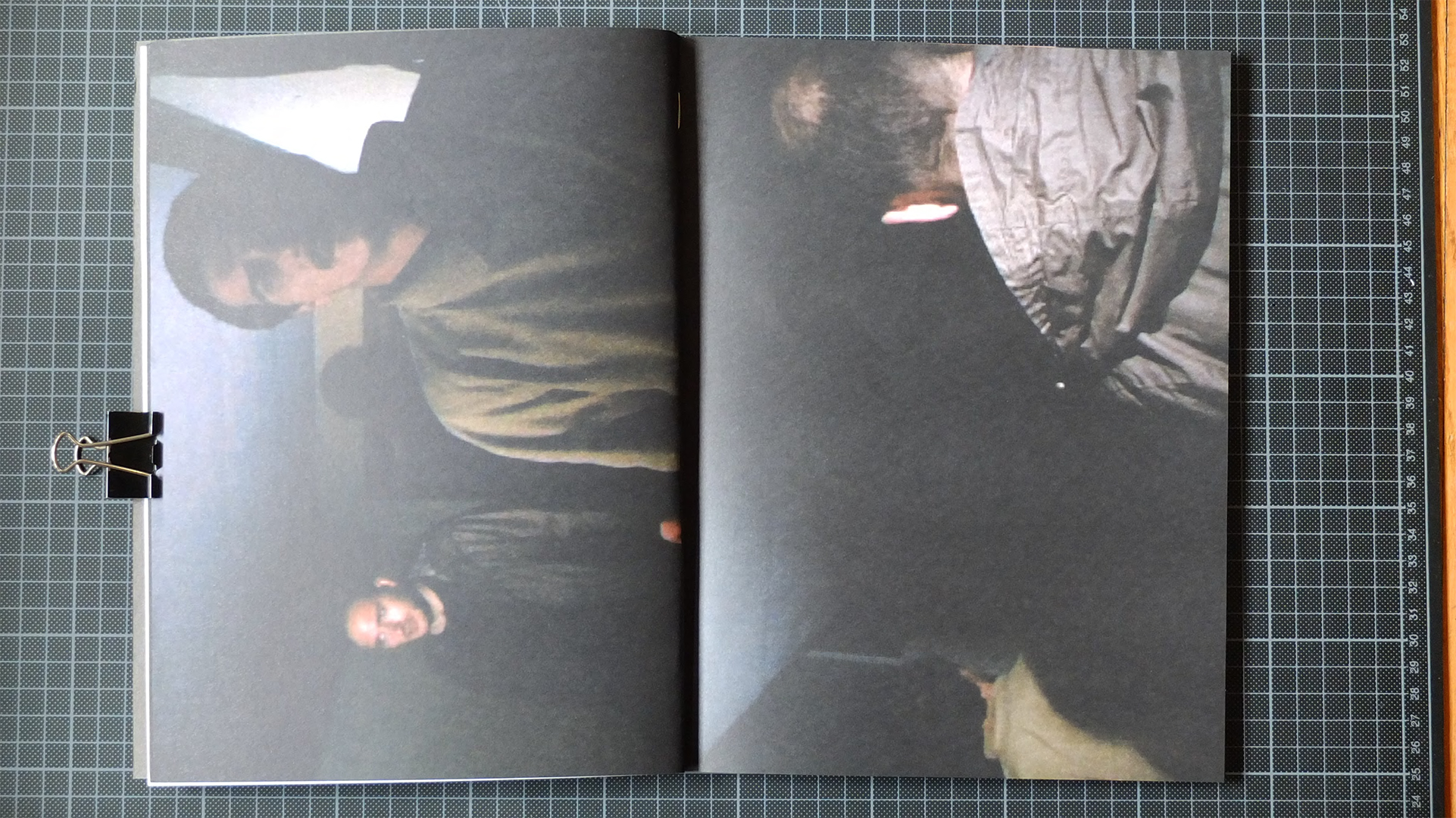

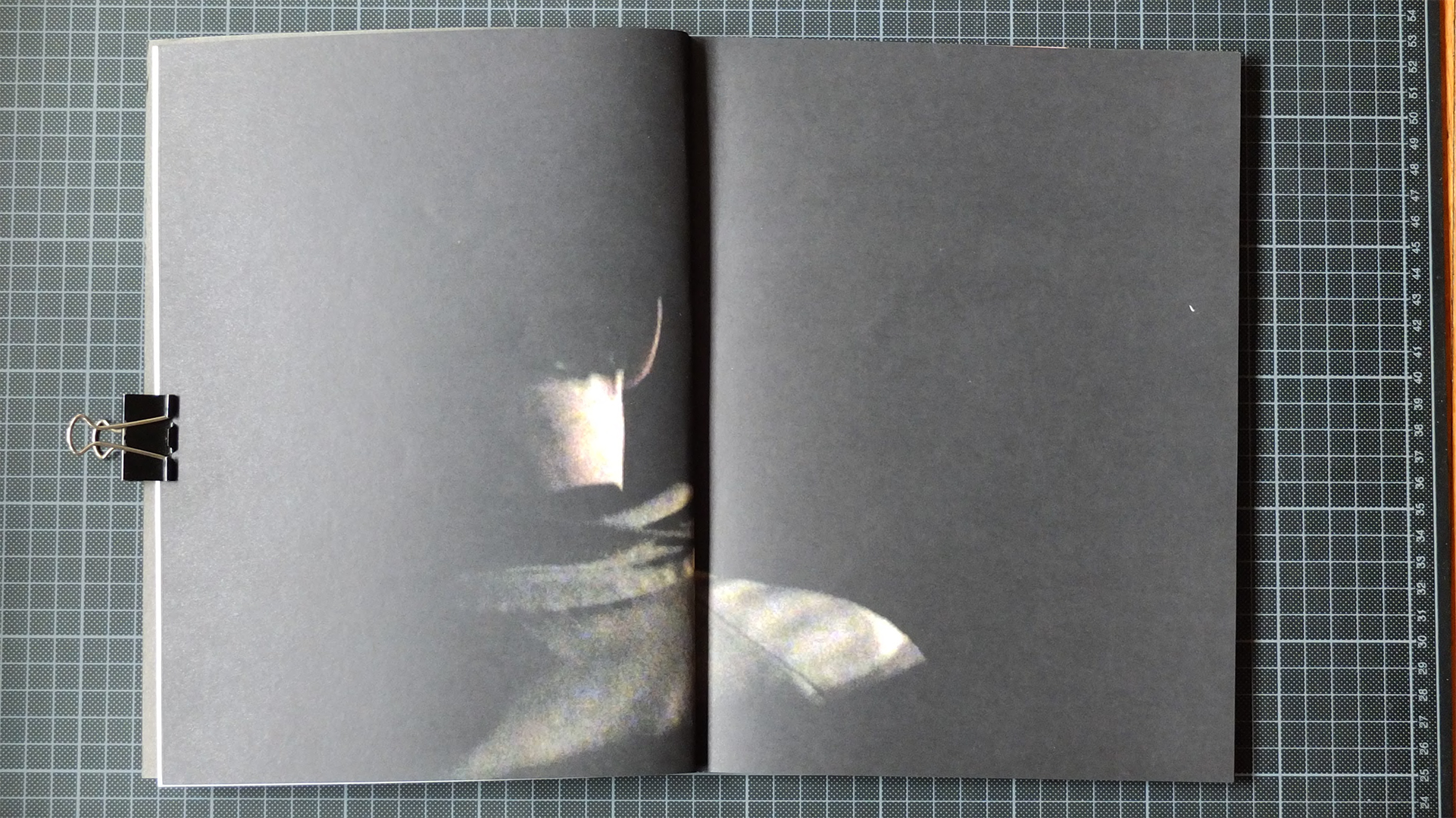

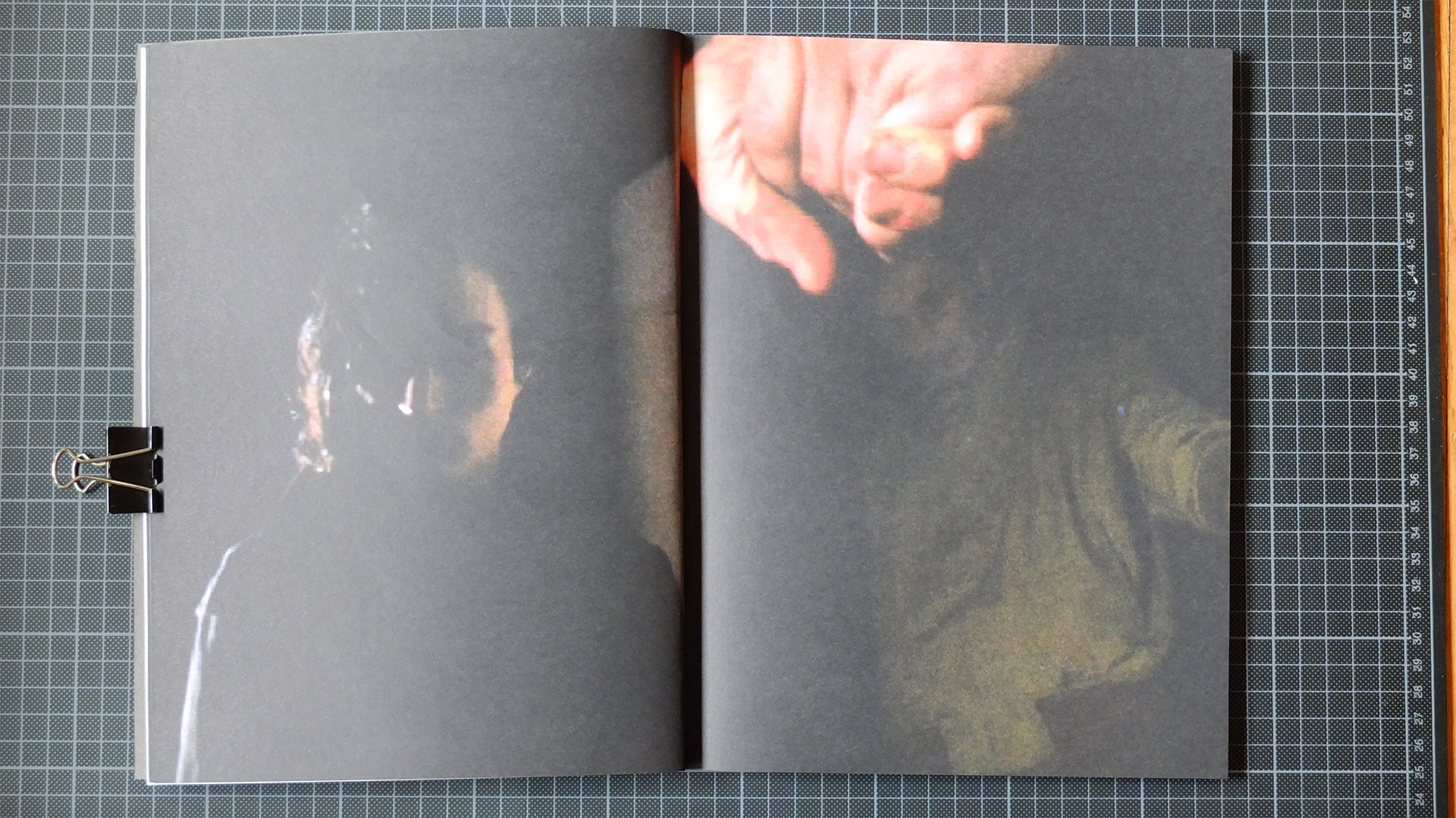

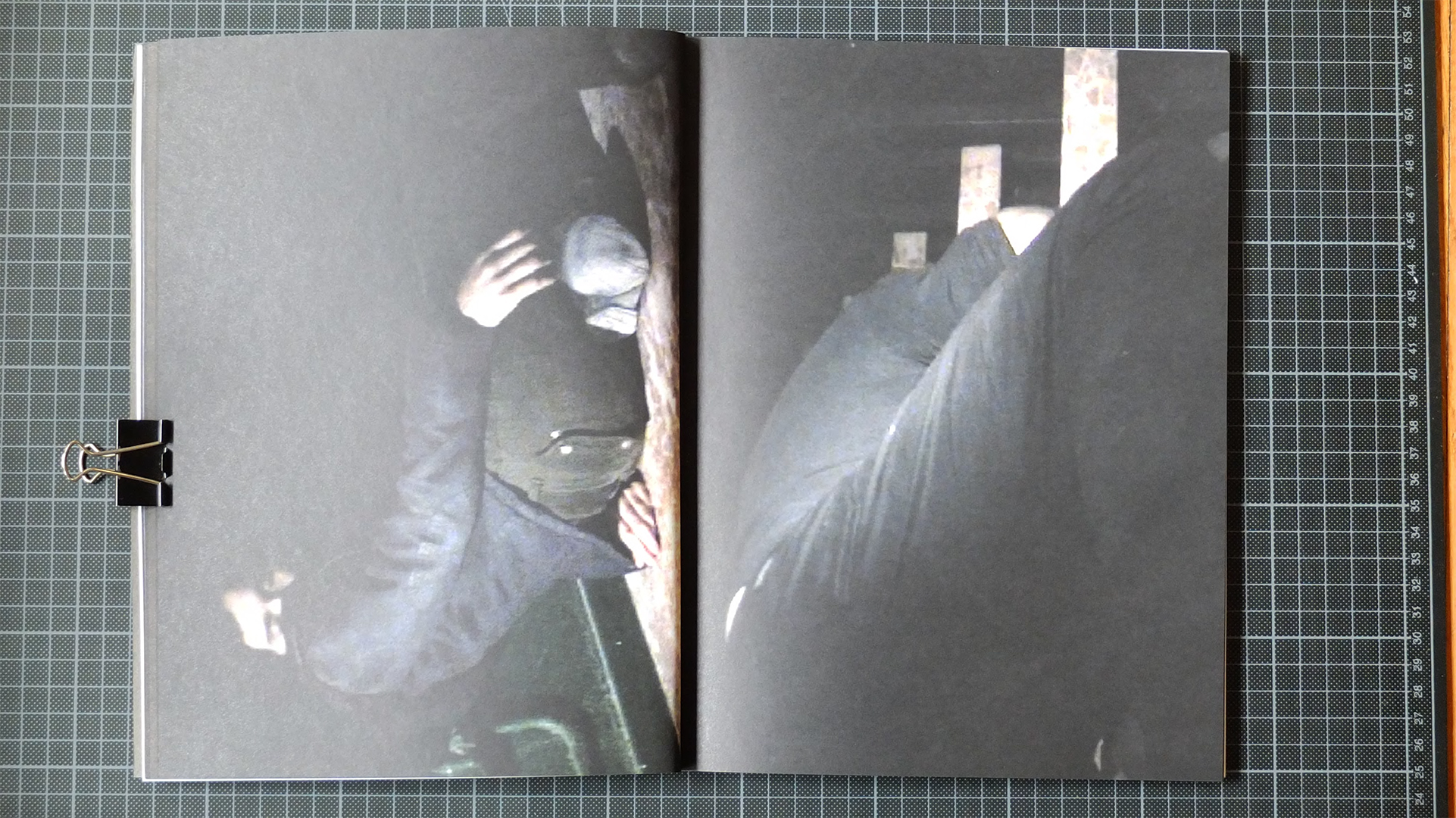

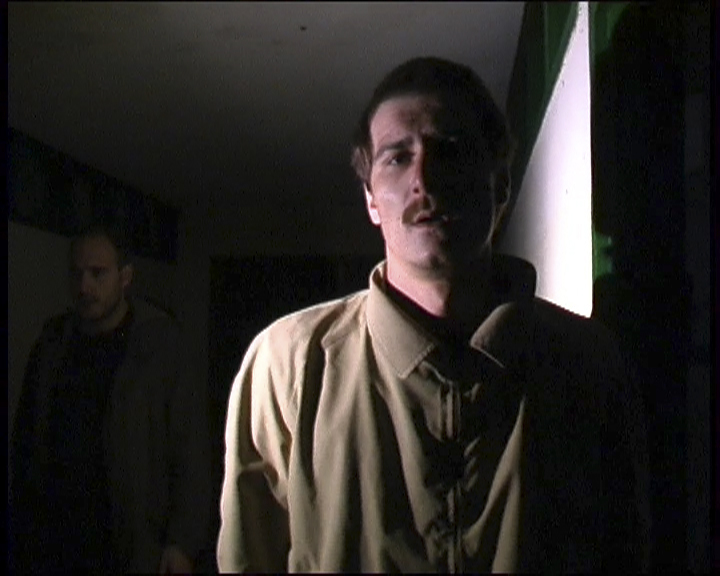

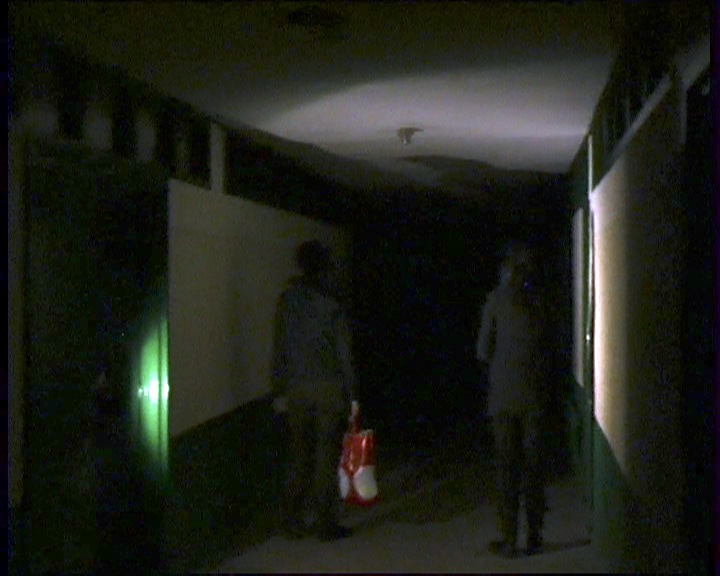

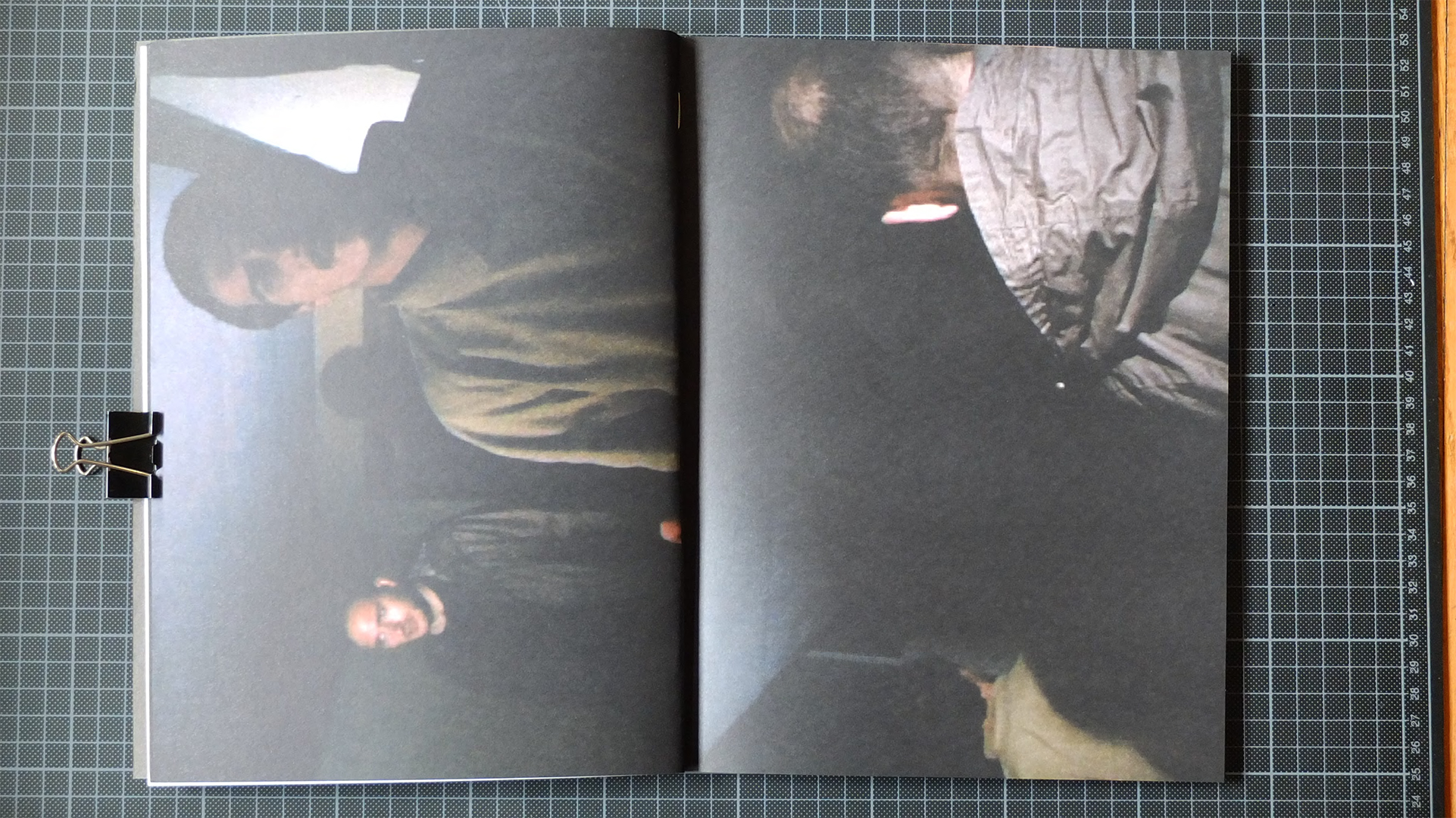

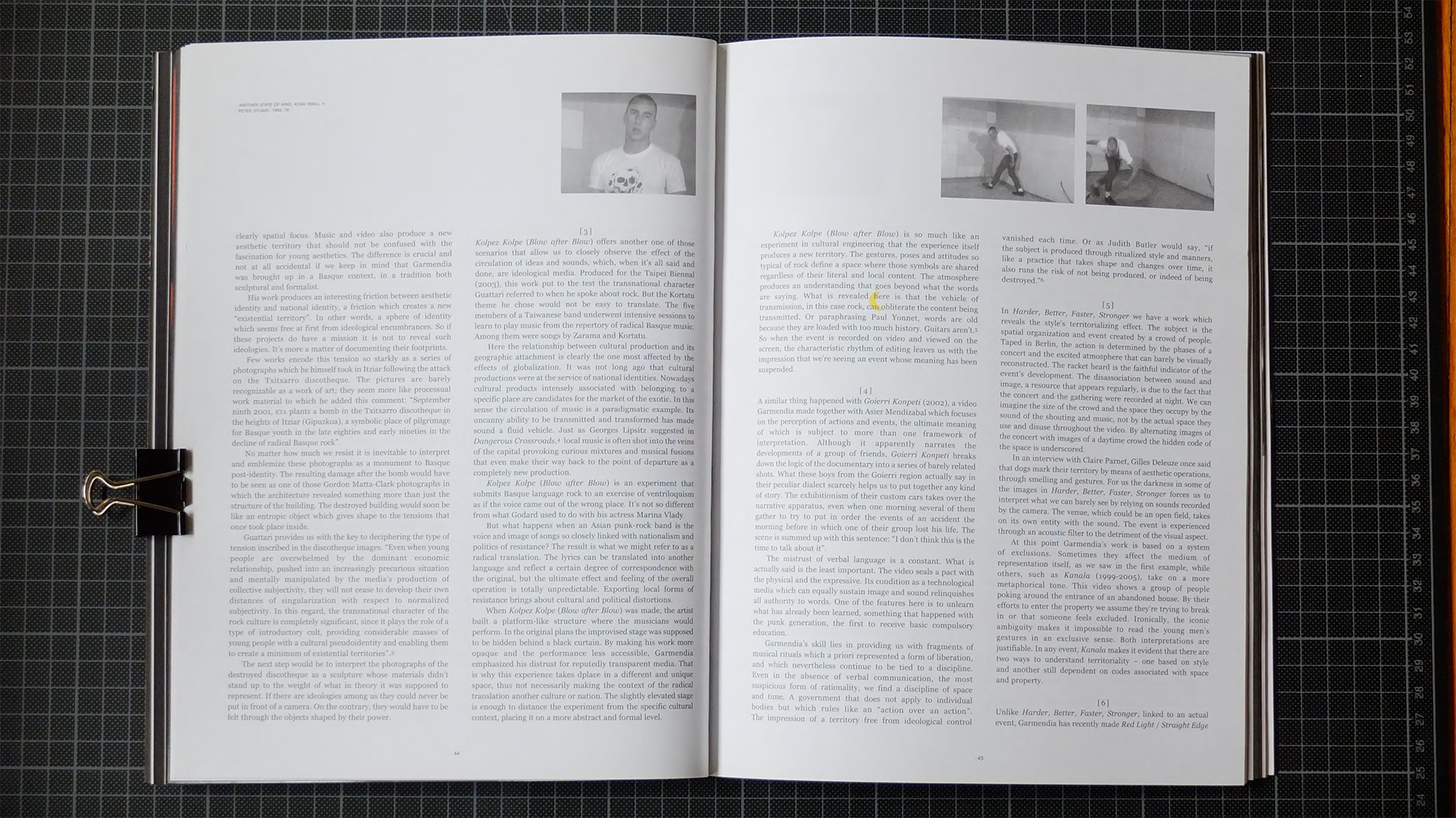

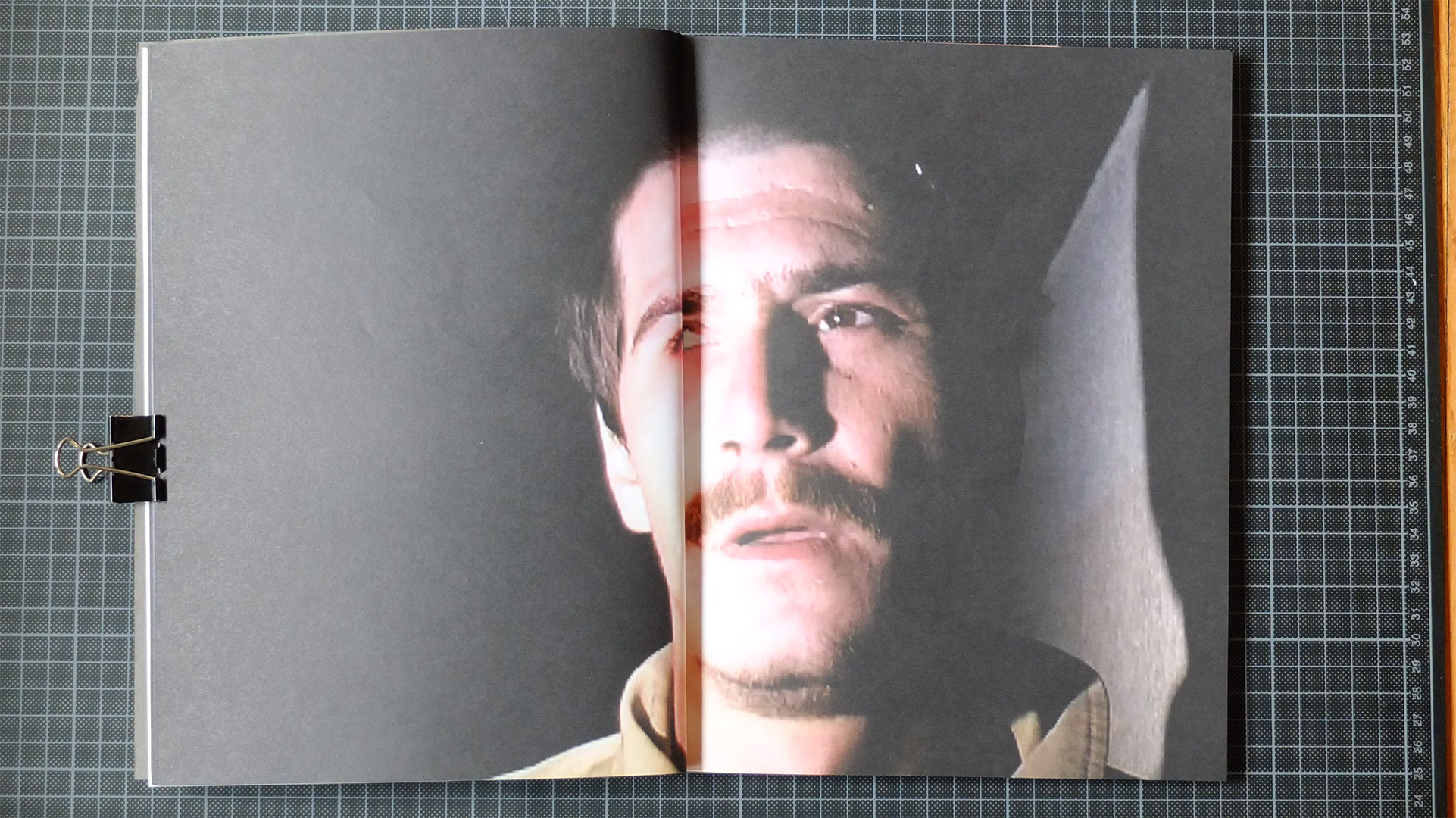

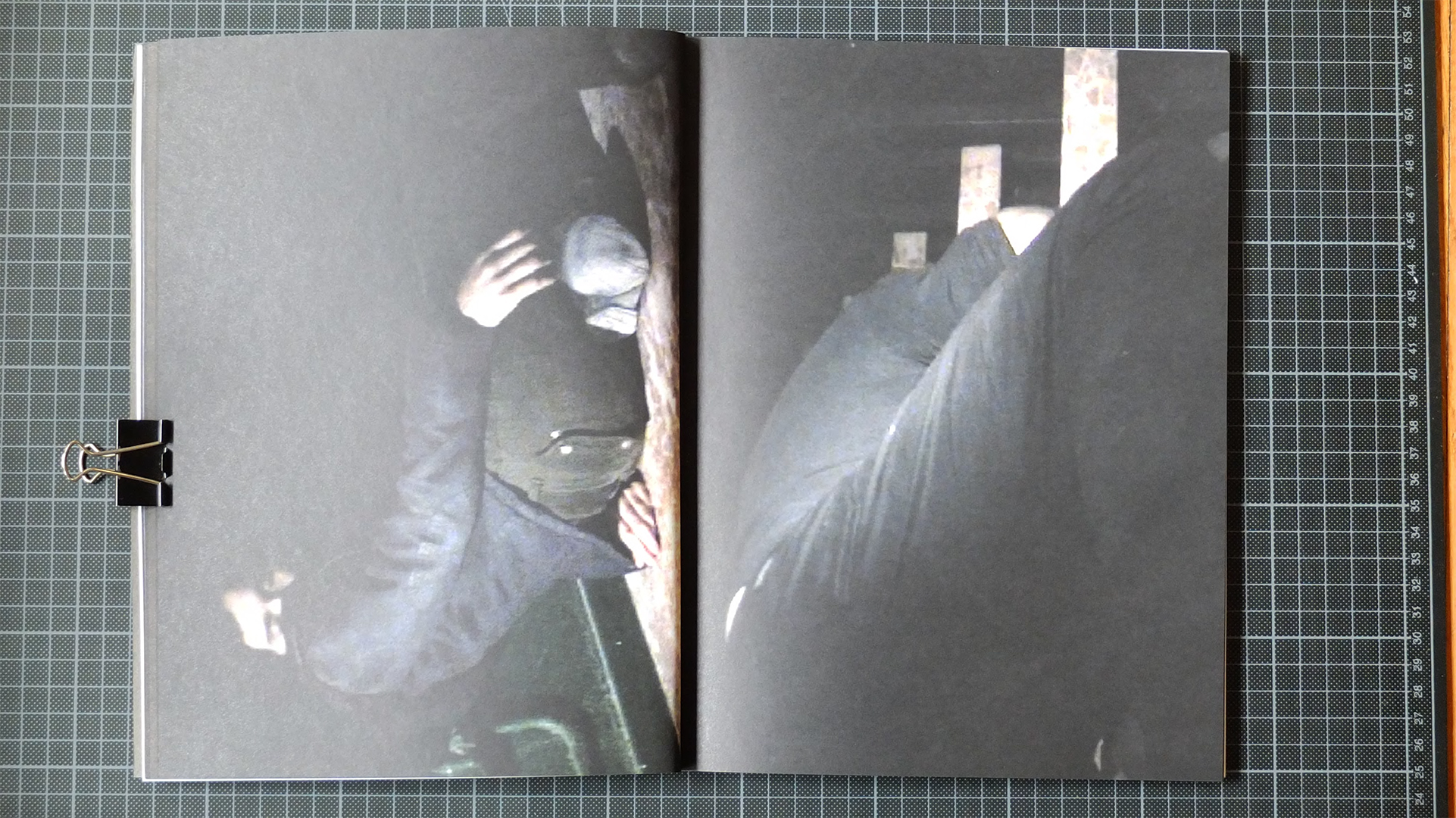

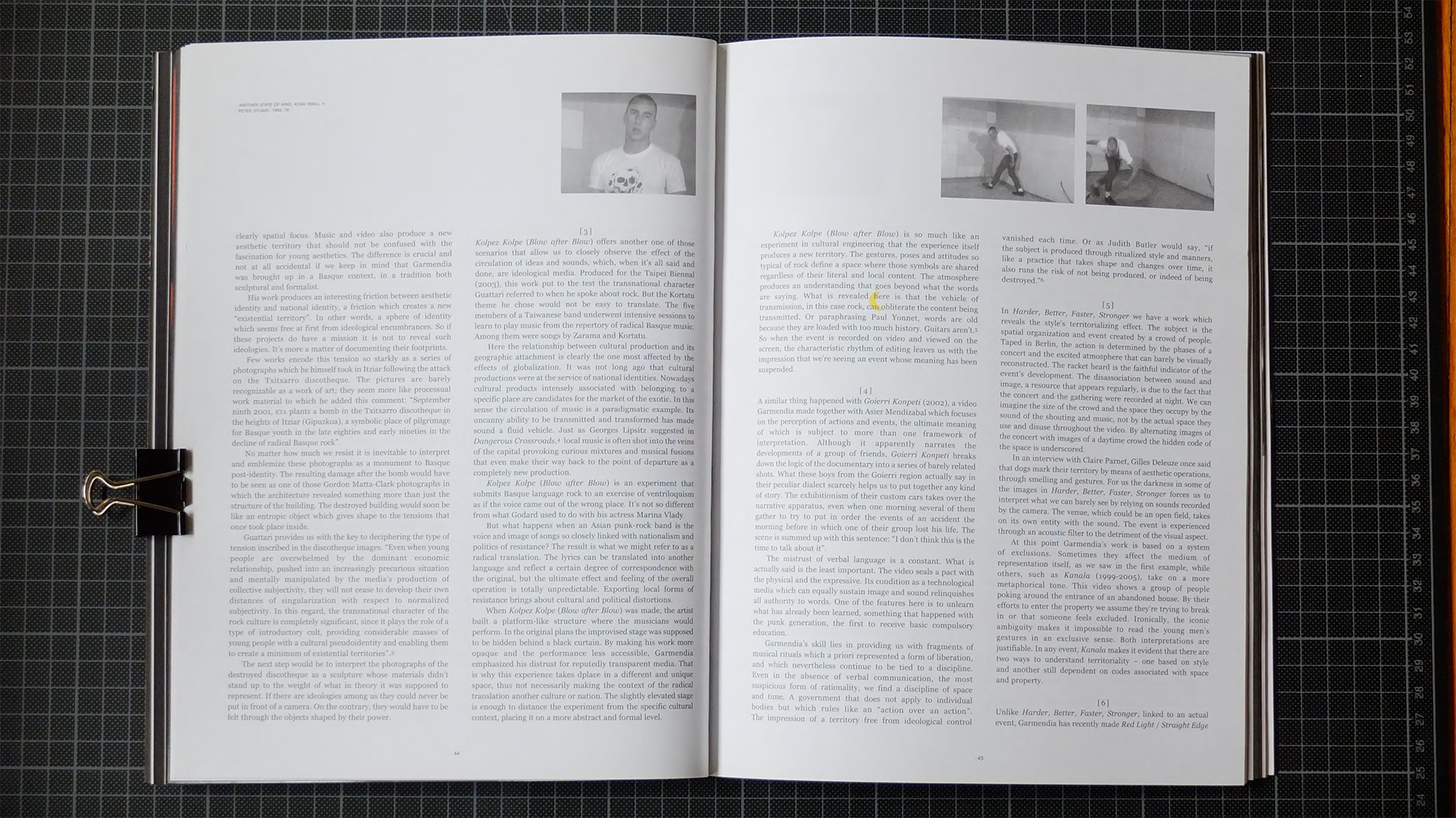

A group video. On this occasion, the instructions are directed at the camera. The spotlight’s white brightness intensifies the shadows on bodies that remain almost static against the darkness of the violated space. The building, an old school for the elite, is abandoned. The opacity and inaction create a strange sensation of otherworldly sluggishness. Once again, the video features Nadia alongside some other people. Some images return from previous works; others burst in from someone else’s footage. An intersecting grammar of self-referential and external elements indicates the way in which culture modifies the life of groups. A scene taken from Adam Small and Peter Stuart’s documentary Another State of Mind (1984) is synthetically reinterpreted. Repetition and difference. A body reproduces the gestural codes of slam dance, a collective form derived from the hardcore scene, as a kind of ephemeral rewriting on the floor of one of the classrooms. The image suggests the link between subculture and class culture, while also evidencing a structure of meaning of its own.

Izarra premiered alongside Red Light/Straight Edge in the individual presentation of the Gure Artea Prize as part of the exhibition Iñaki Garmendia, Ibon Aranberri, Azucena Vieites, Artium, Vitoria-Gasteiz (2004).

Related bibliography

→ Gure Artea : XVIII. Vitoria, Montehermoso Kulturunea, 18 December 2004 – 6 February 2005; Artium-Basque Museum of Contemporary Art, 27 October 2005 – 8 January 2006.

Juan Antonio Álvarez Reyes: ´Gure Artea : vasque technique = ¿Técnica vasca? en Artecontexto, nº 9, Madrid, invierno 2005, p. 118-119.

Carles Guerra. “La postidentidad vasca”, Culturas, 14/12/2005, p. 20.

Galder Reguera: “Contemporary Art in the Basque Country : Young Basque Art”, Lápiz : Revista Internacional de Arte, Madrid, no. 212, April 2005, p. 46-63.

→ Speaking of others : “Red Light/Straight Edge“; “Izarra”. Frankfurt, Frankfurter Künstverein, 7 June – 13 August 2006.

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

Javier Viar. Historia del arte vasco: de la Guerra Civil a nuestros días, 1936-2016. Bilbao : Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 2017, vol. II, pp. 589, 923, 1093, 1113, 1135, 1151-1158, 1183, 1188.

The History of Basque Art compiled by Javier Viar. Two volumes bringing together more than 300 artists from the postwar period to the present day. With chronological presentation of Garmendia’s career, from his period in training, through principal works and exhibitions to 2013. Inlcudes reproductions of Izarra (2005) [fig. 403; p. 115] and Sin título (verja) (2011) [fig. 404; p. 1156].

Pablo Marte. «Sector Conflictivo. #02: Iñaki Garmendia», Basilika. Podcast, 85 min. 31 sec.

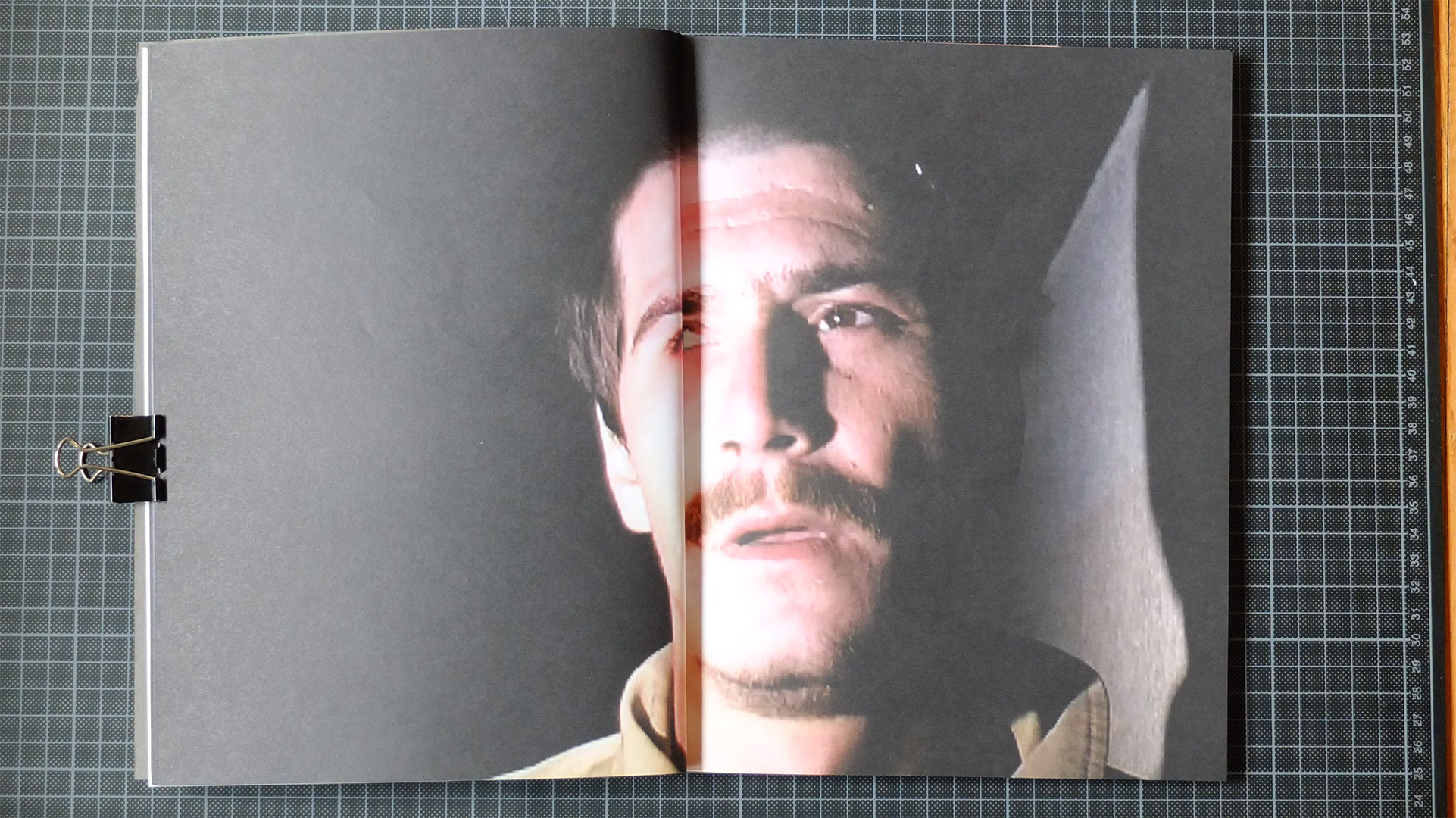

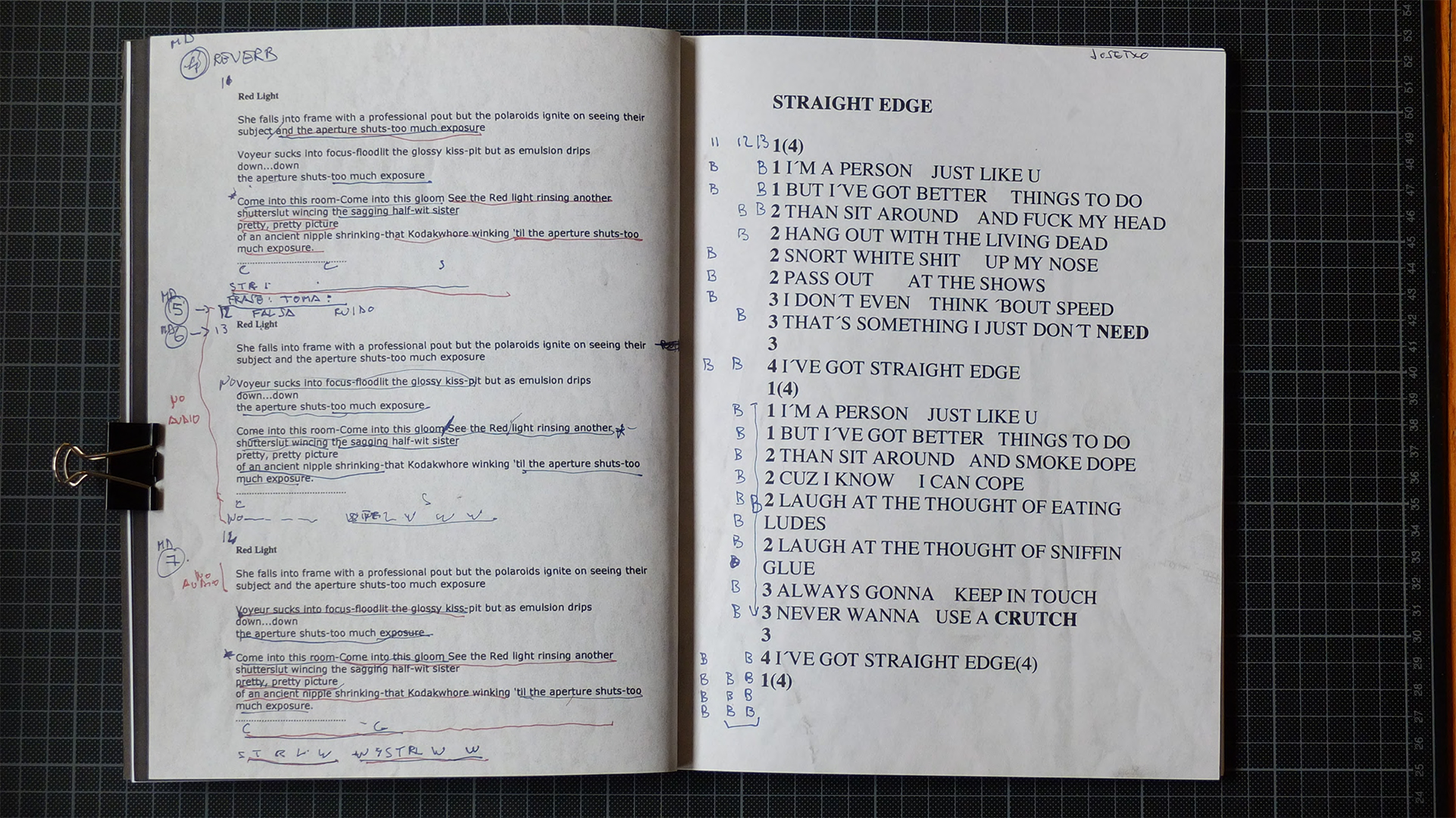

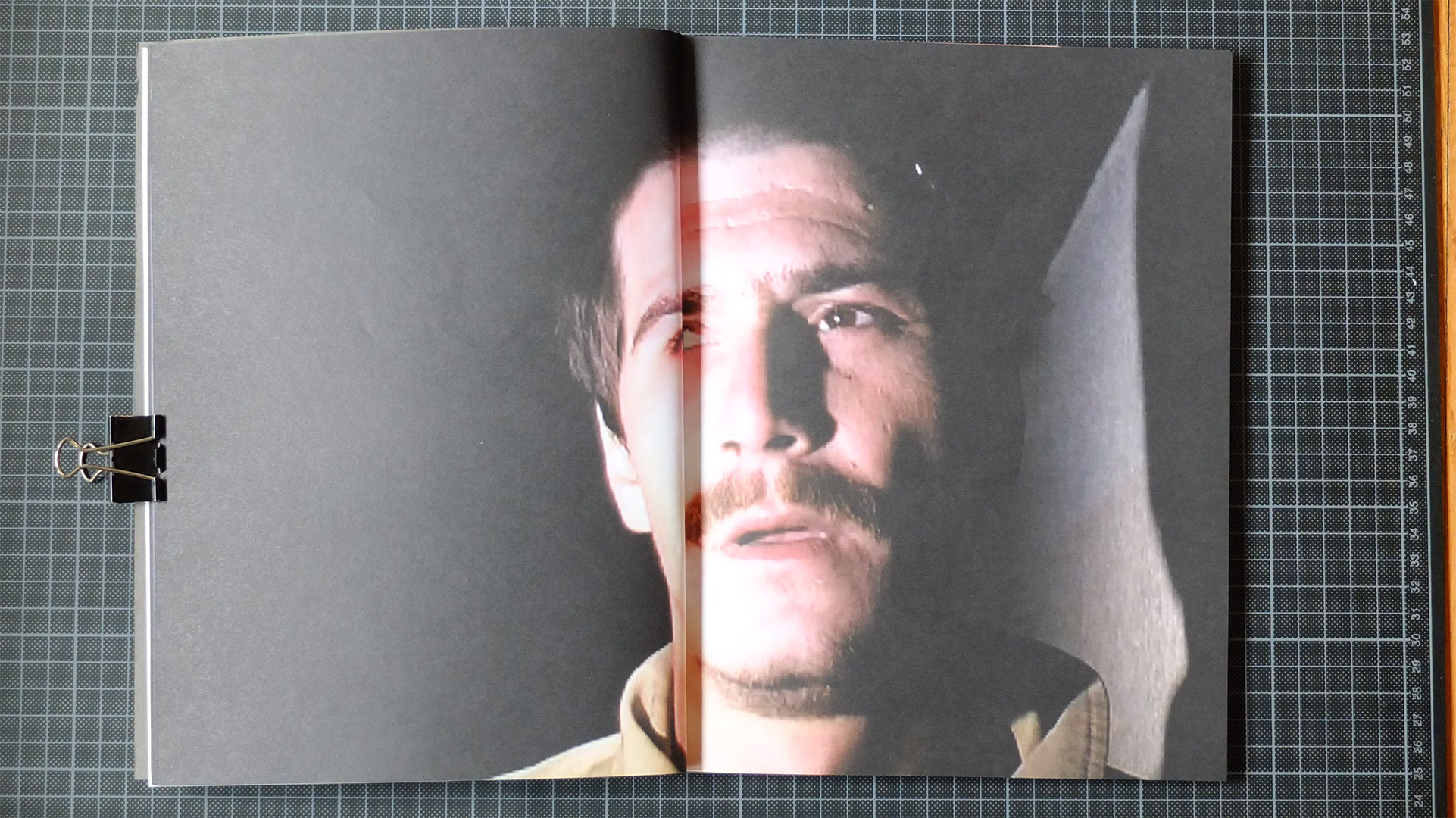

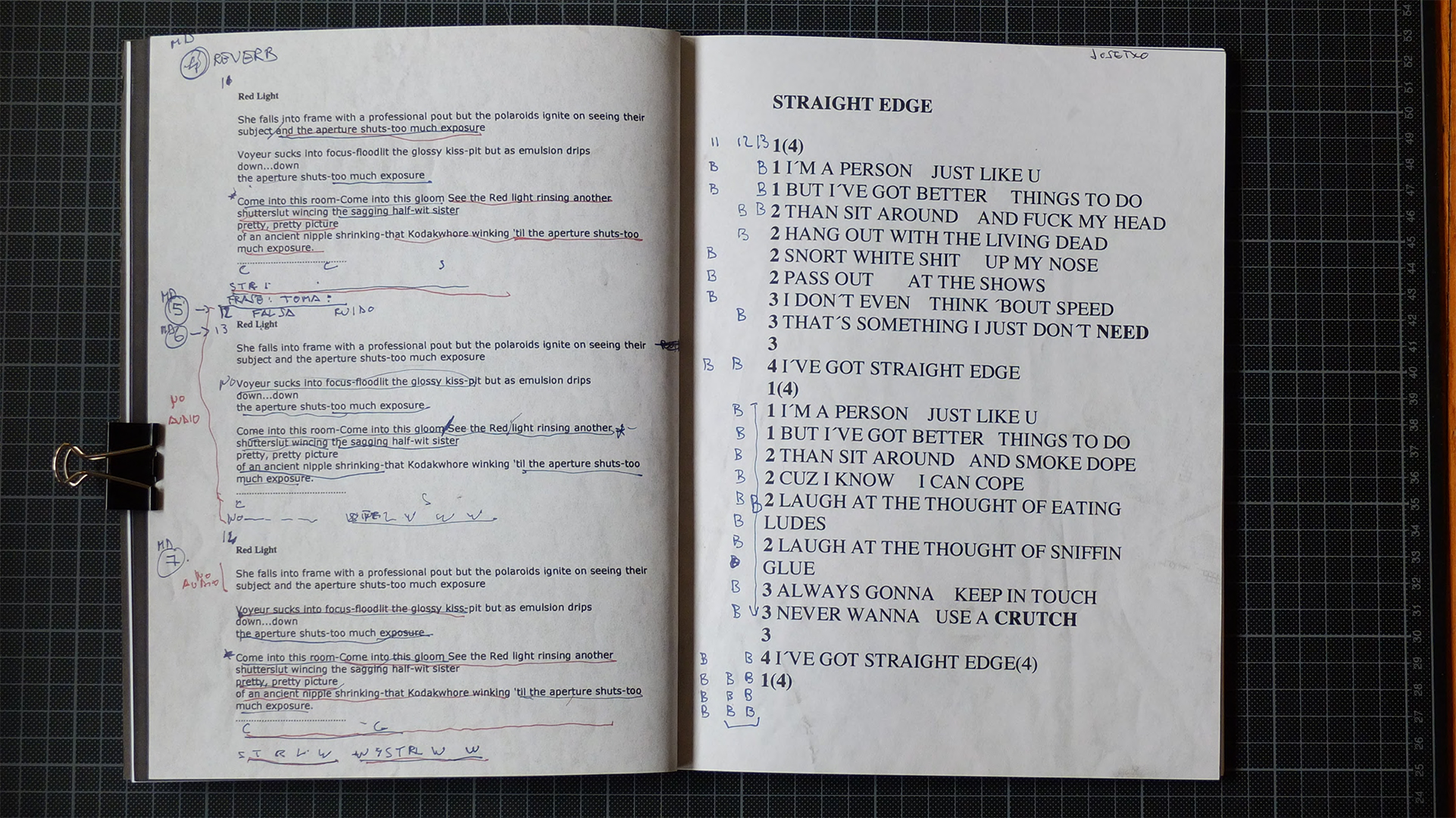

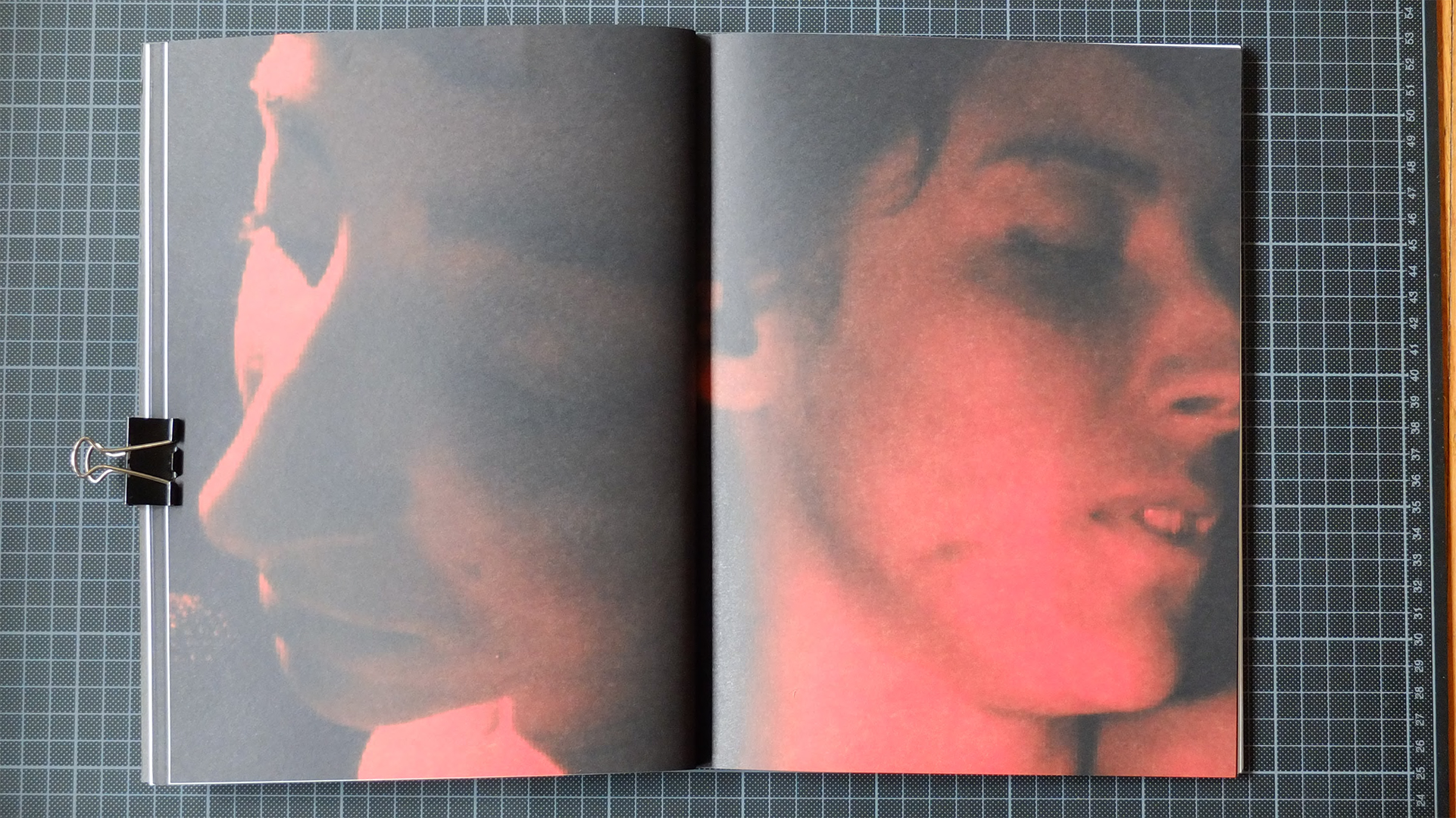

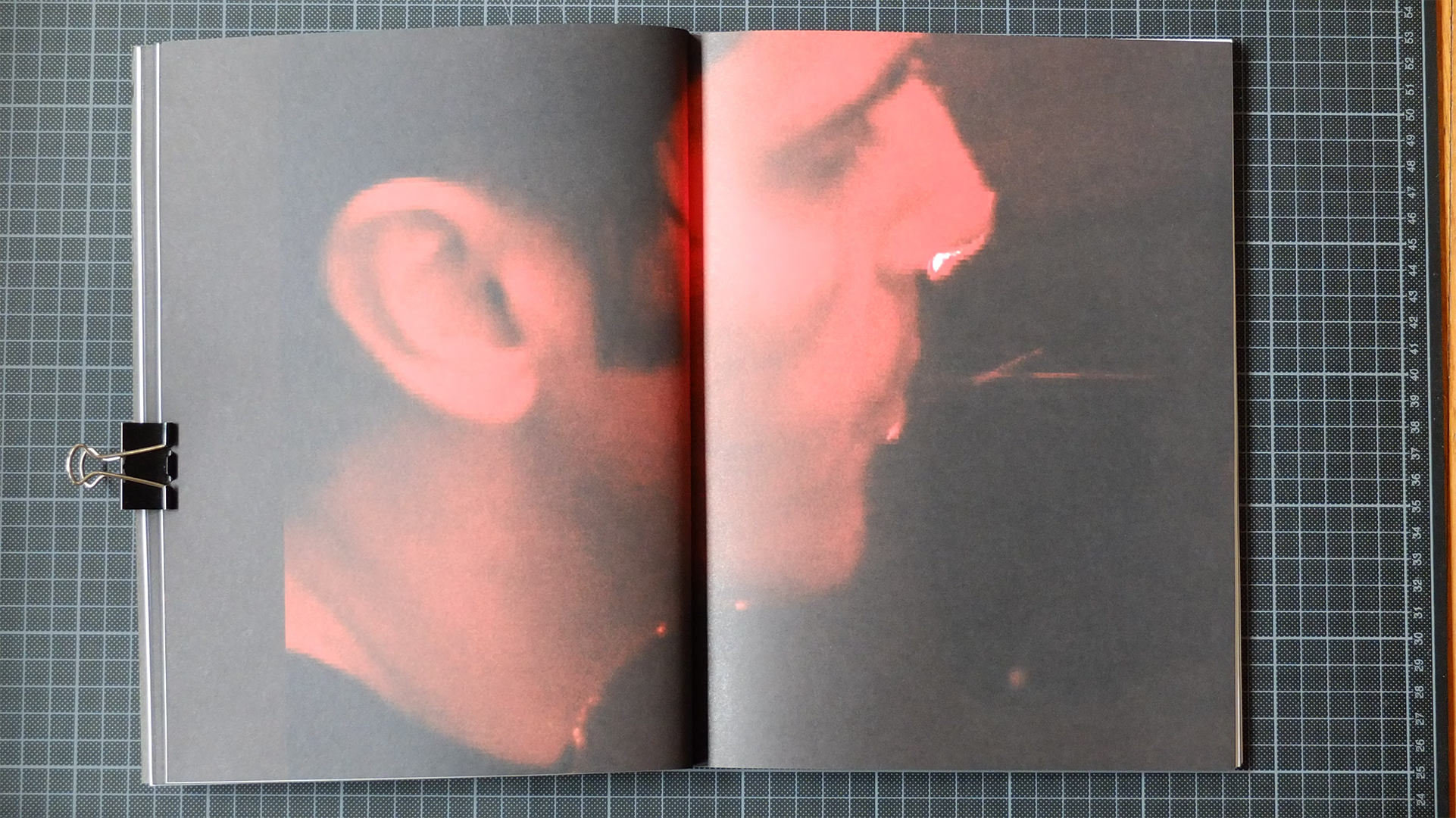

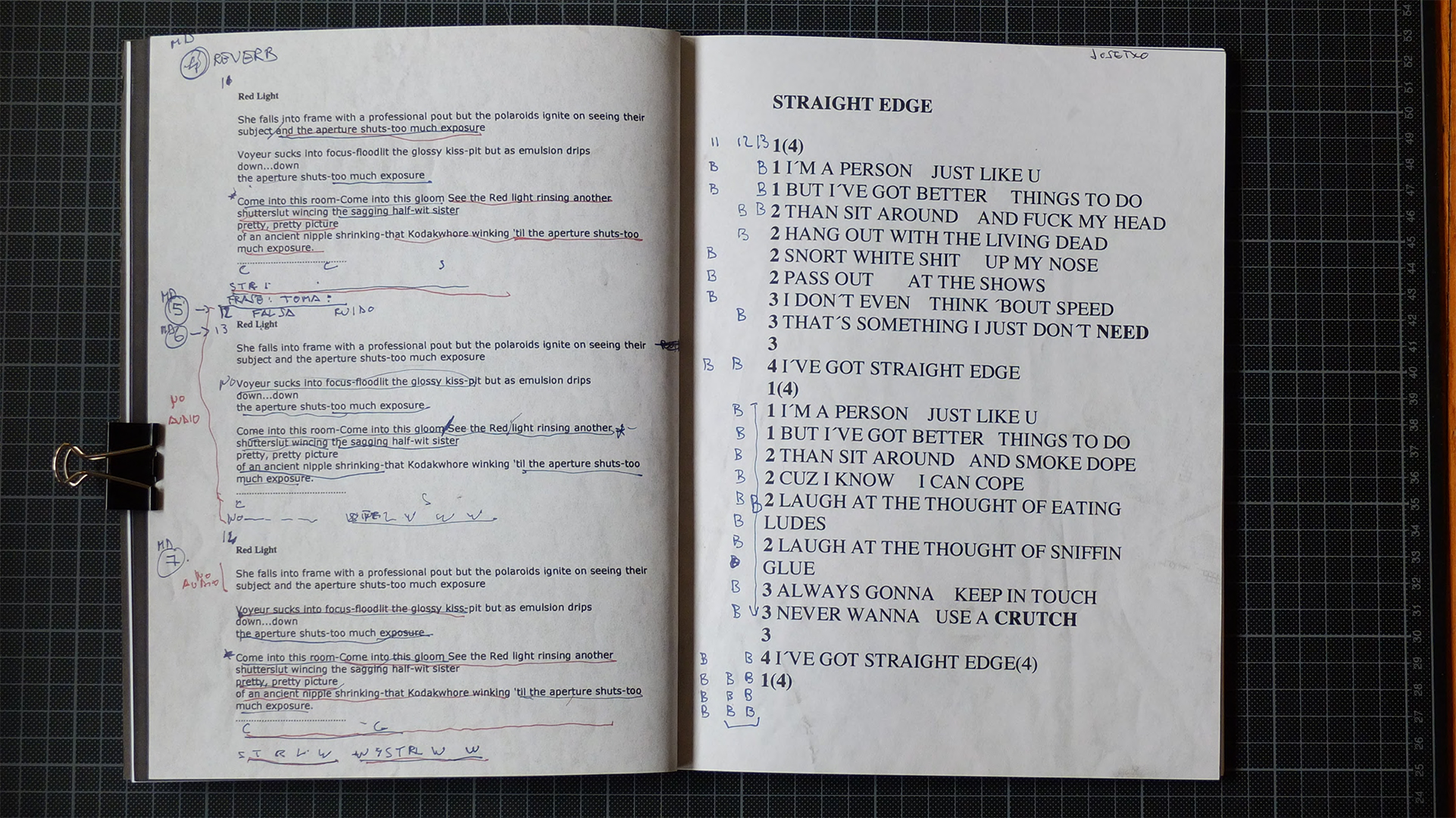

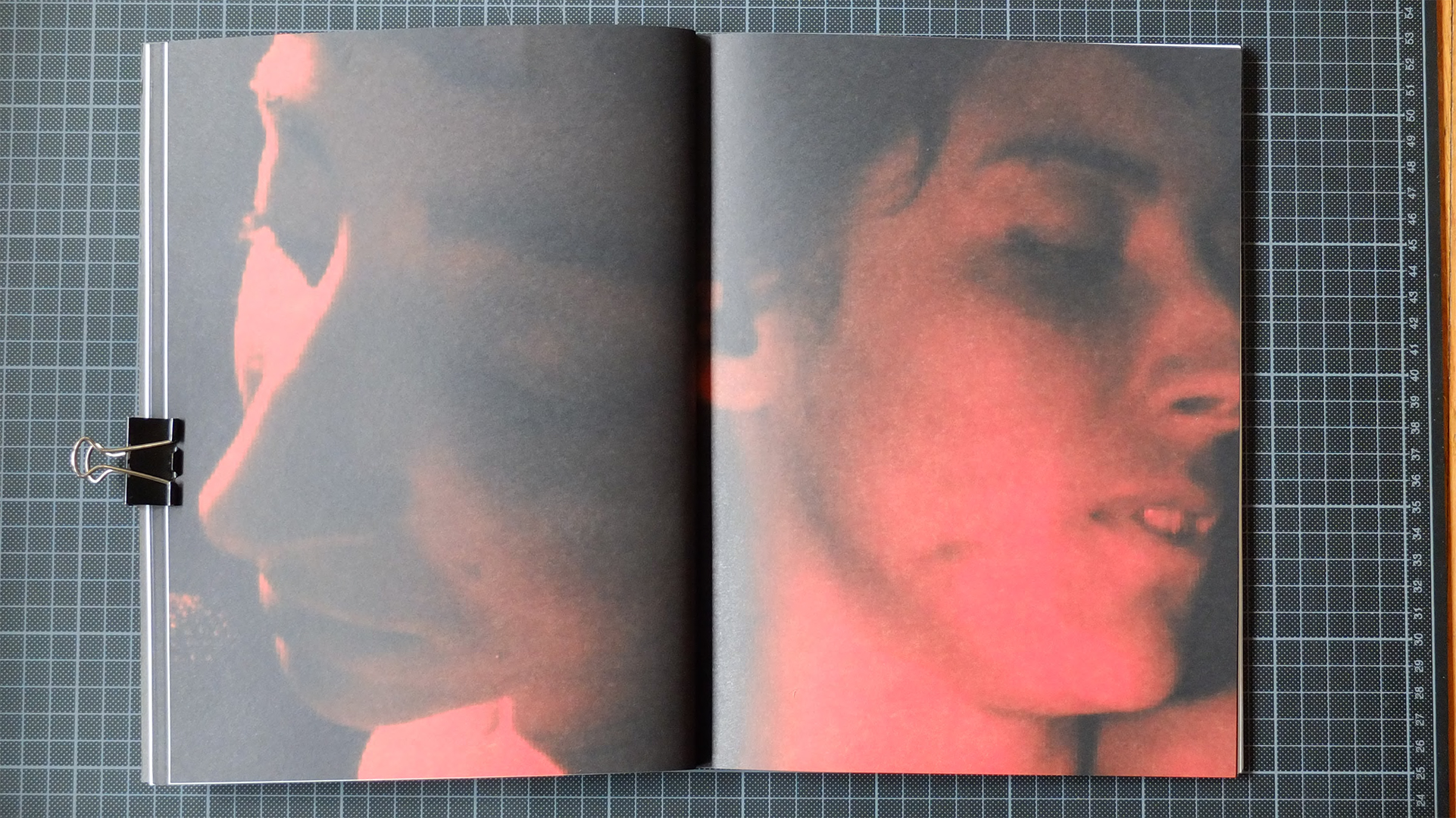

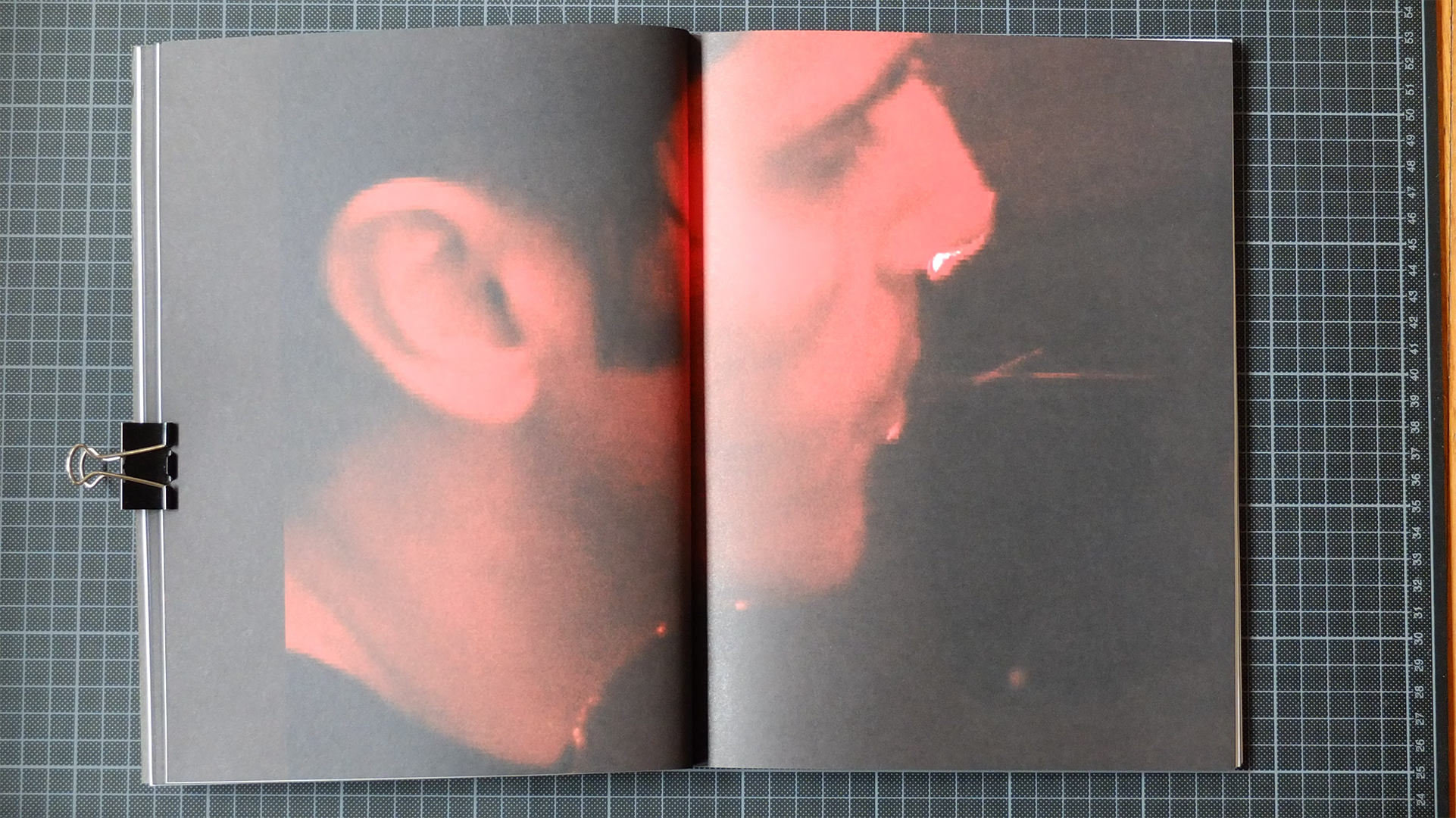

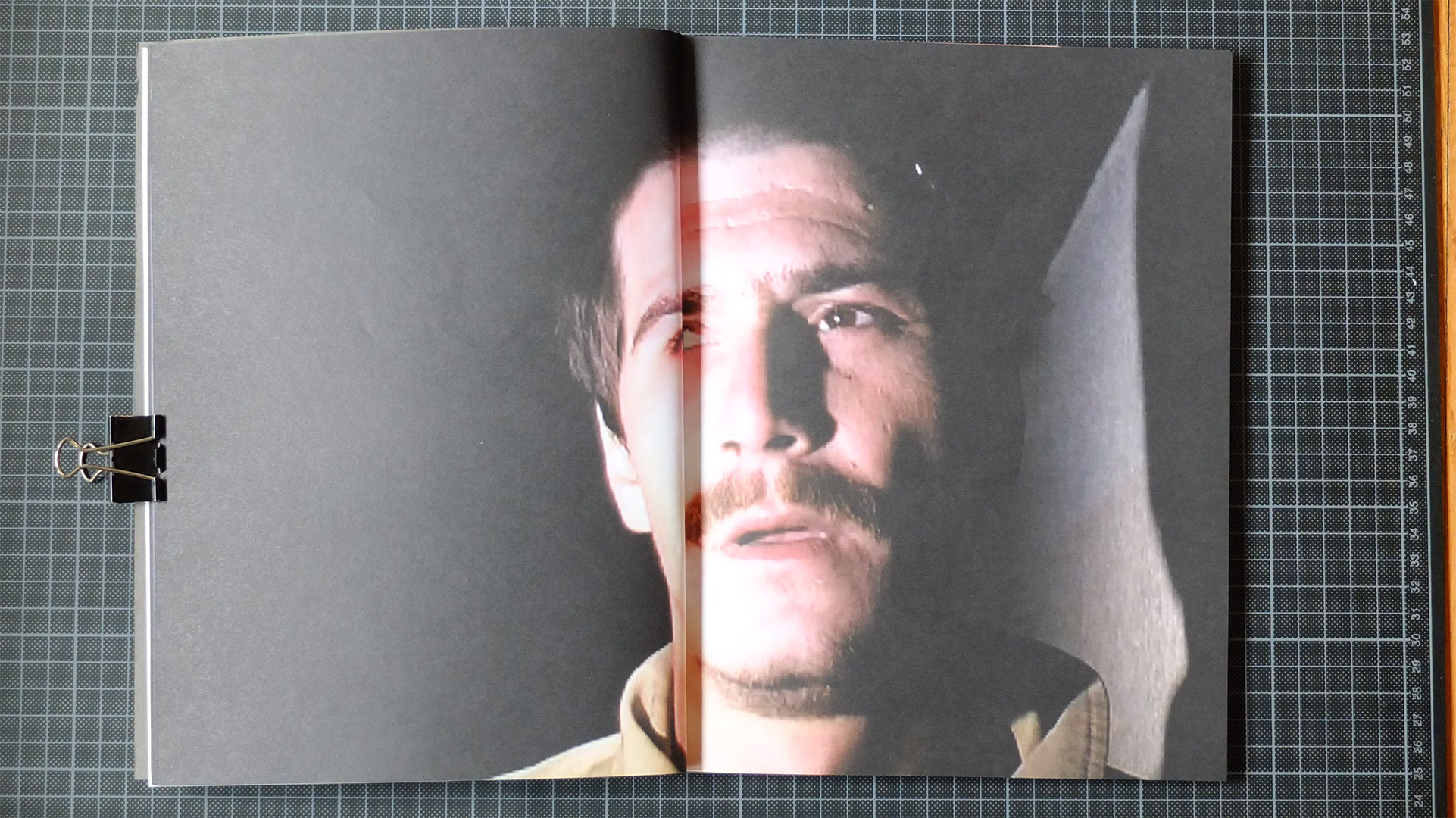

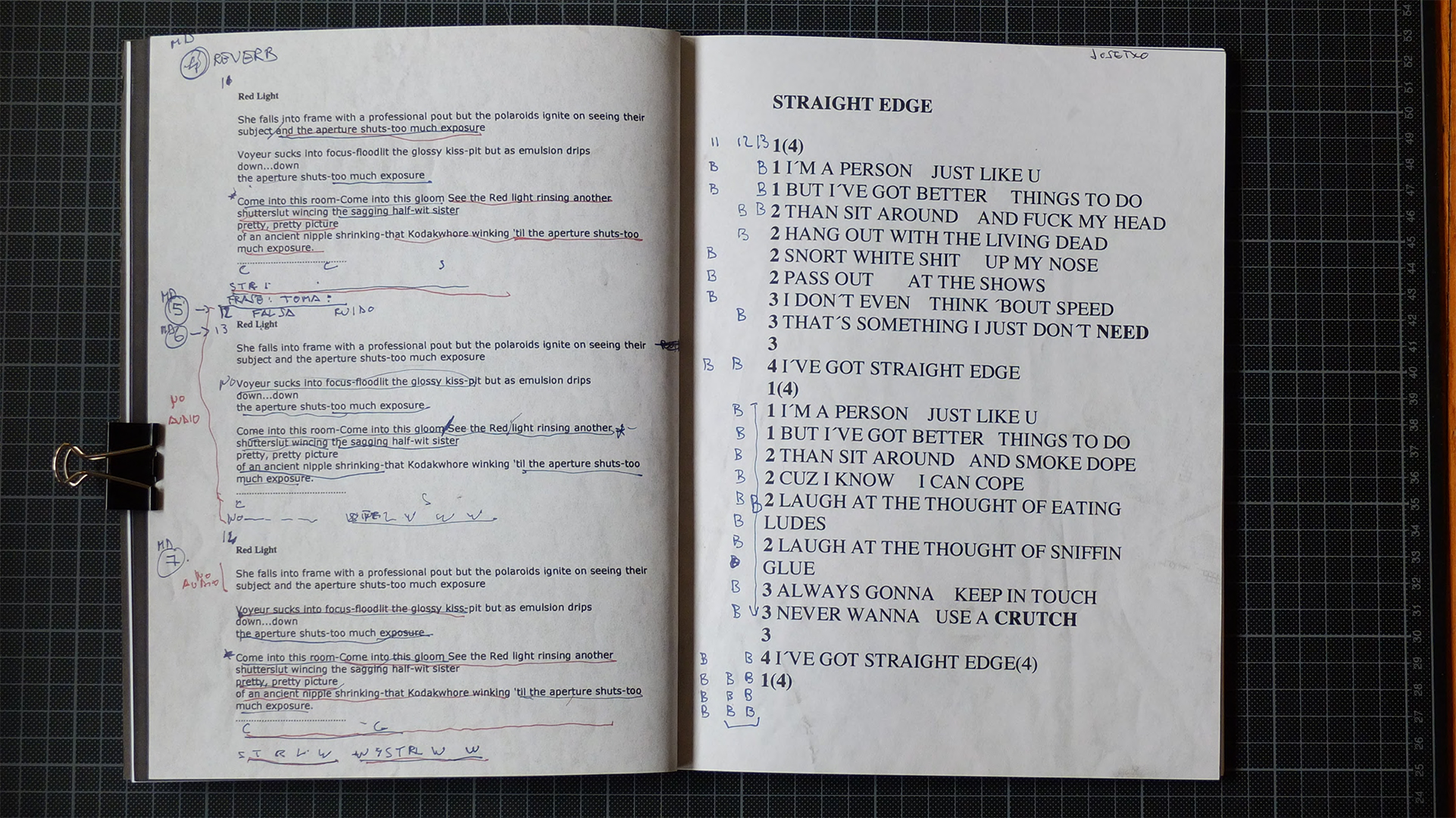

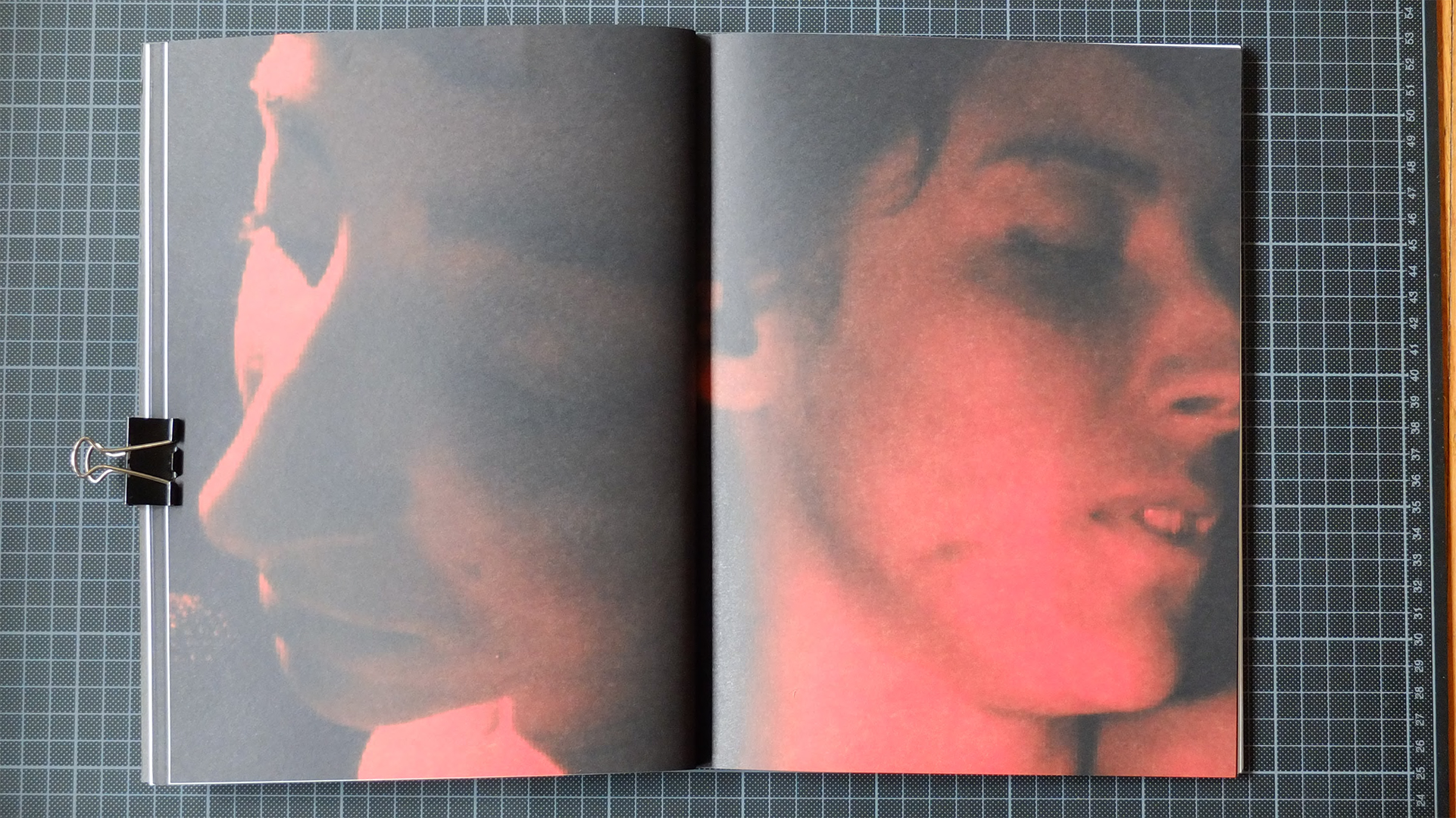

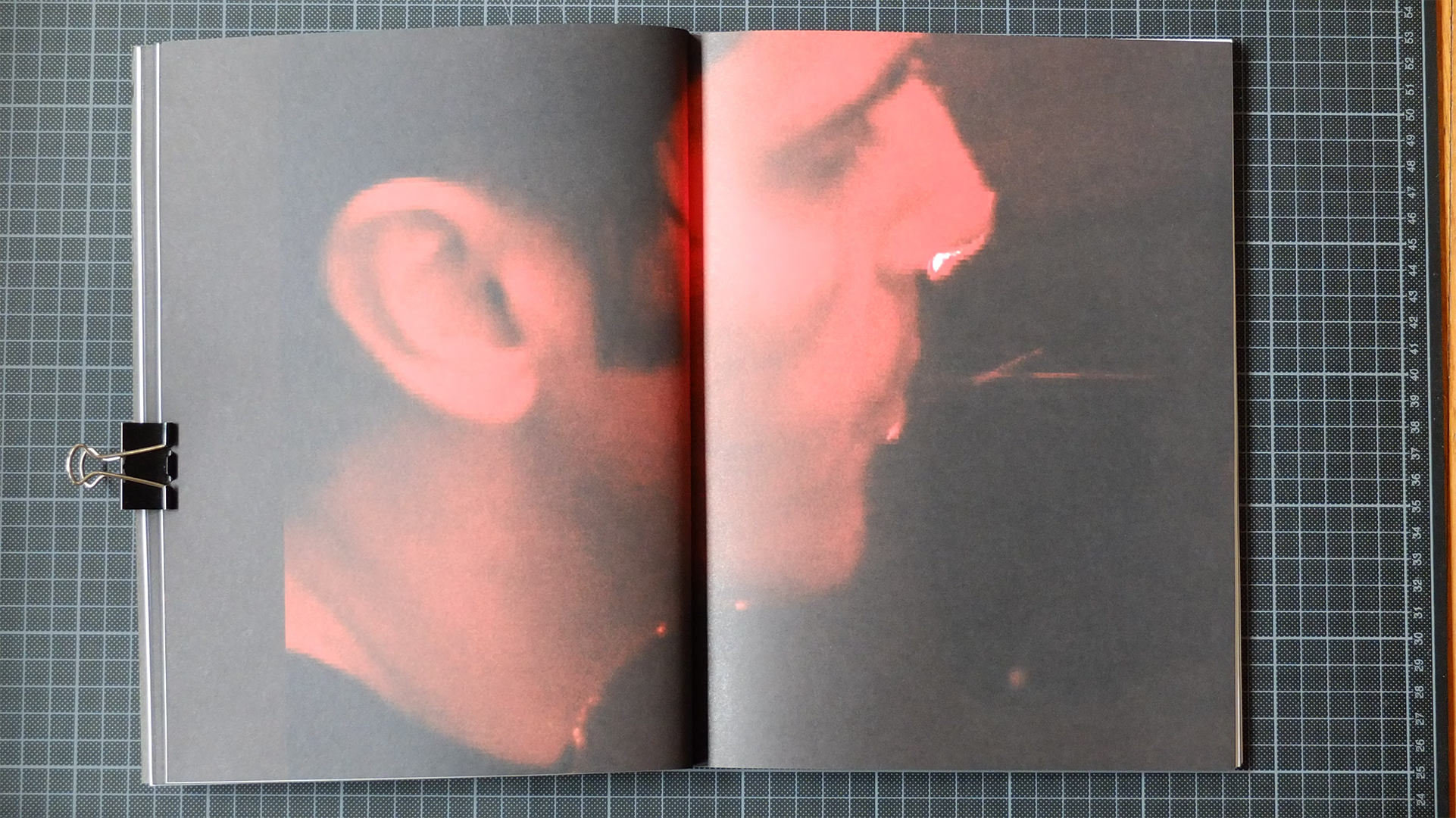

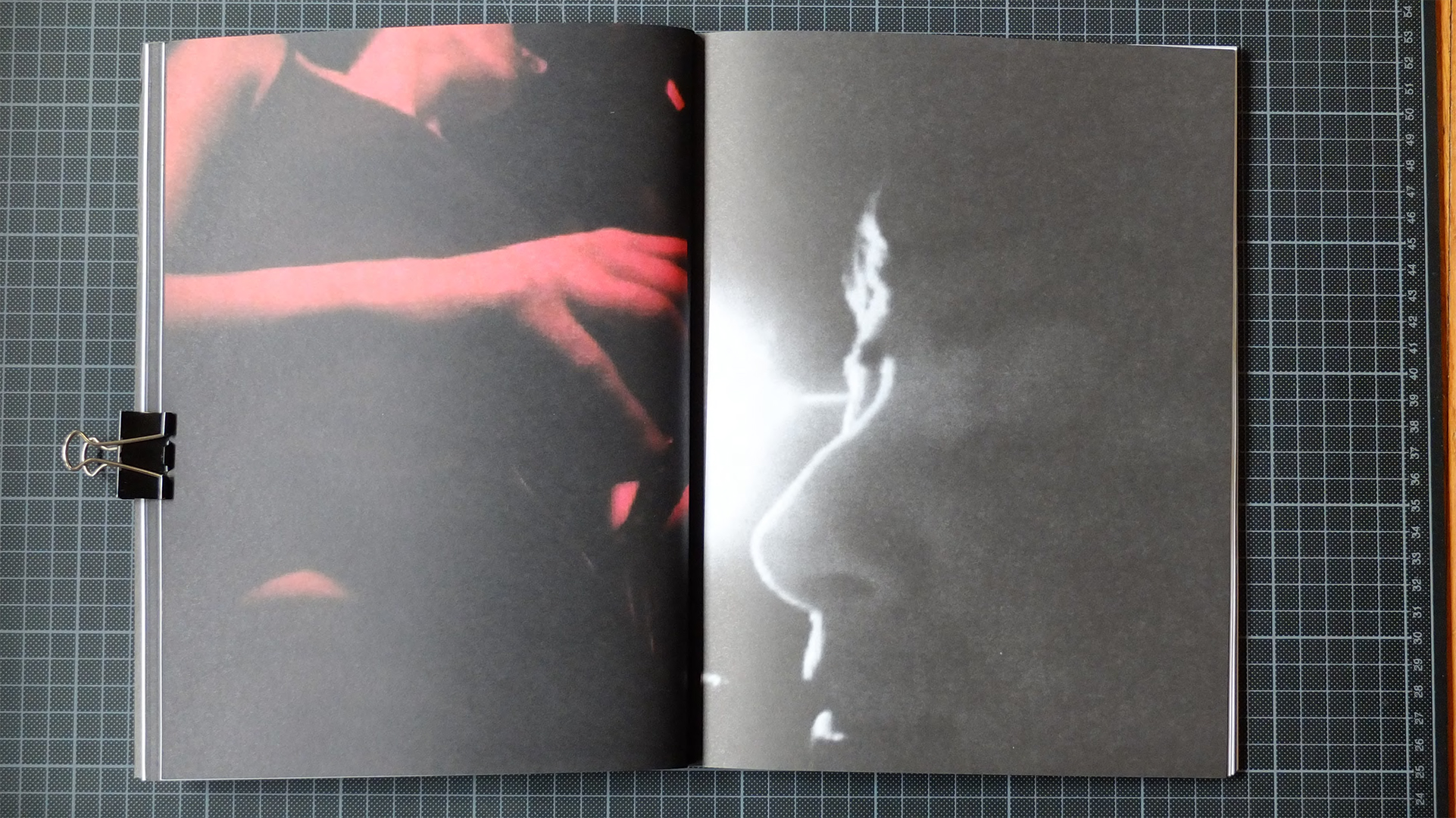

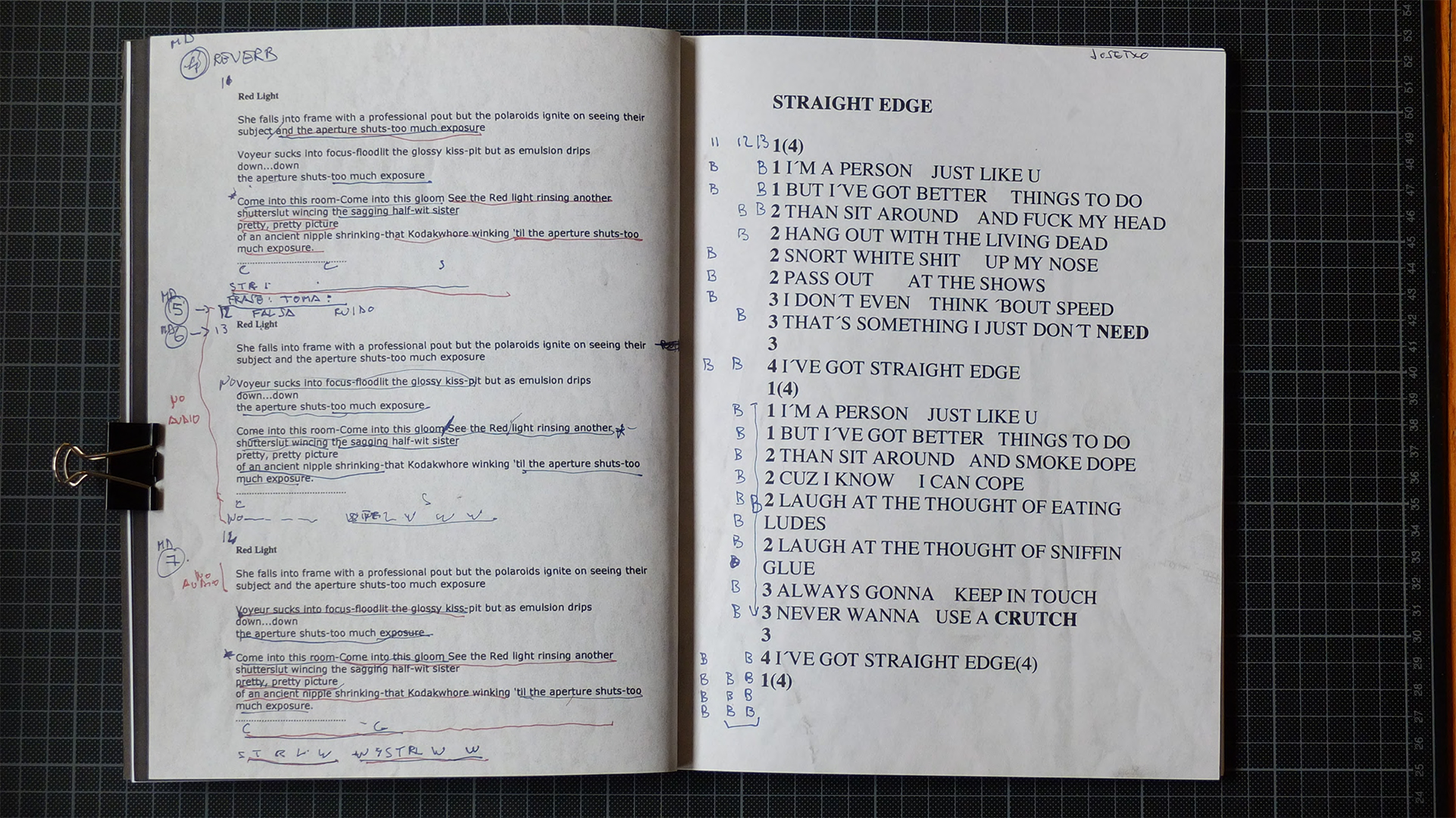

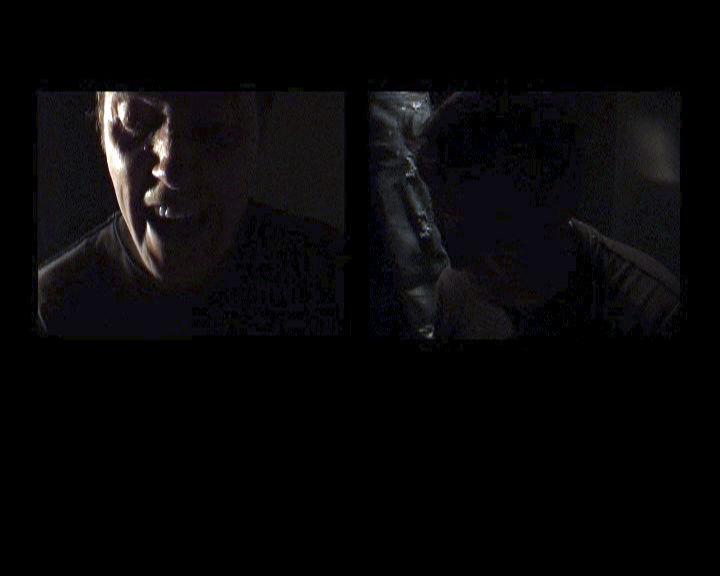

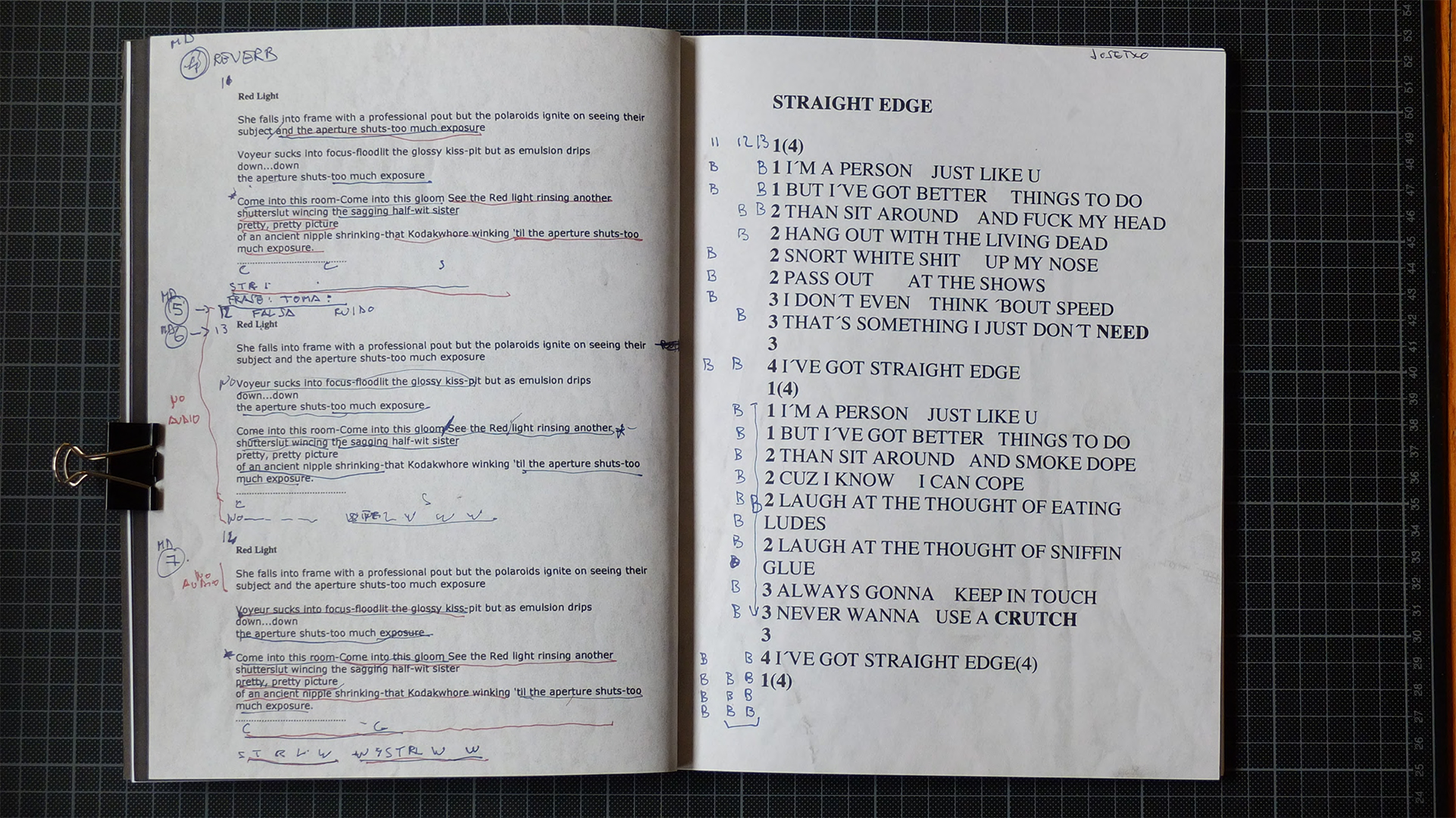

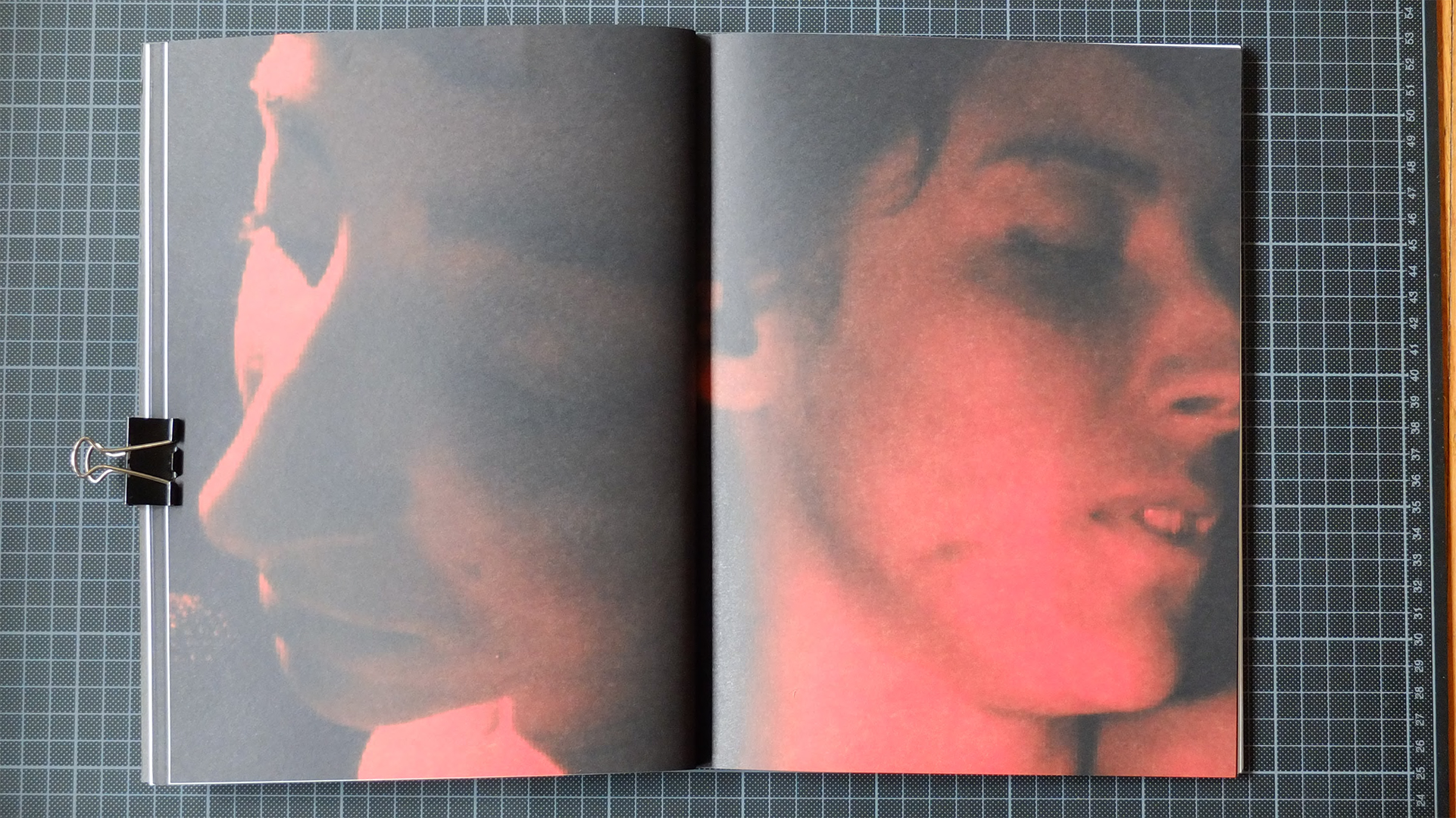

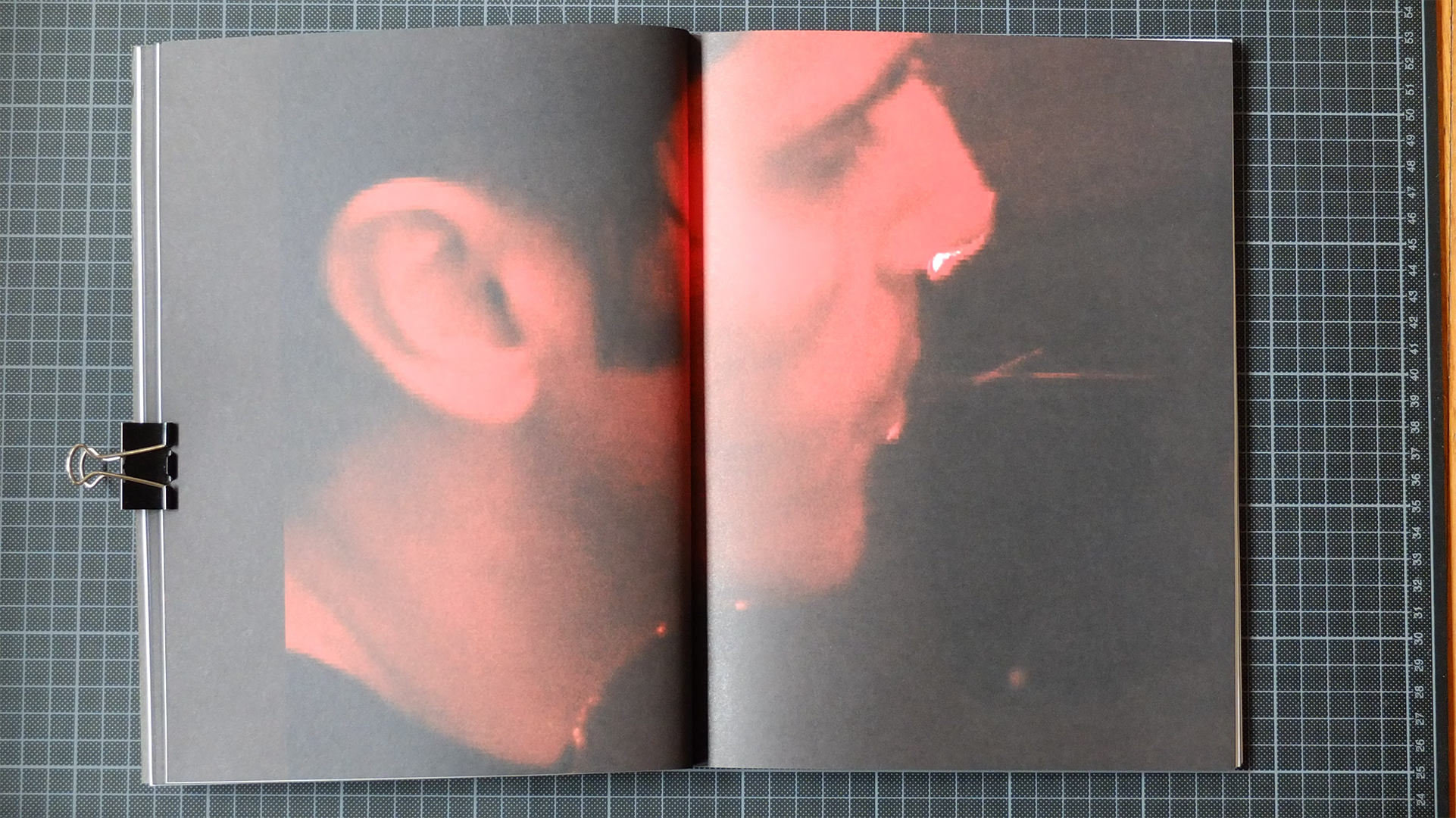

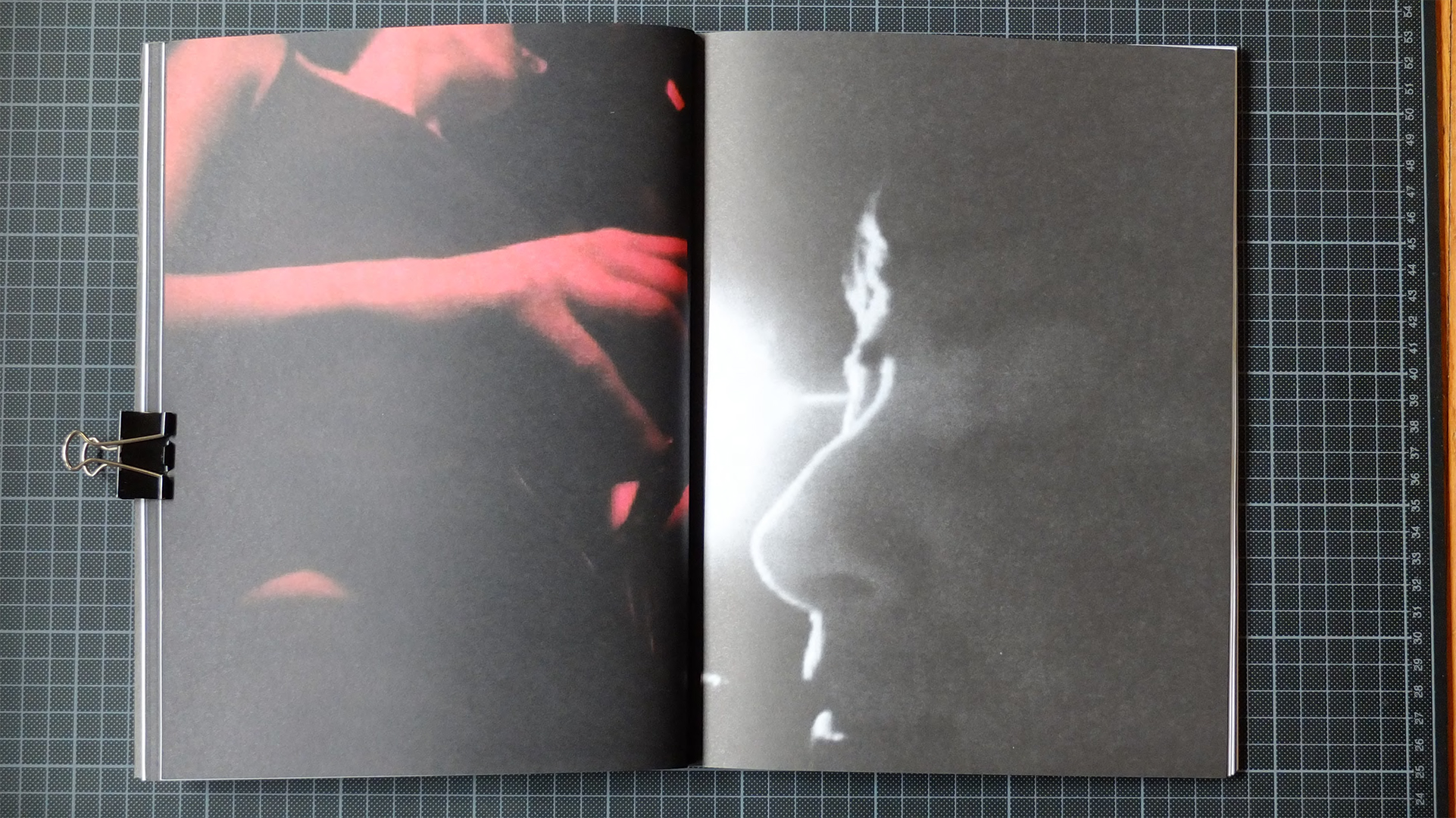

Two-channel video, with sound, colour

6’ 29’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

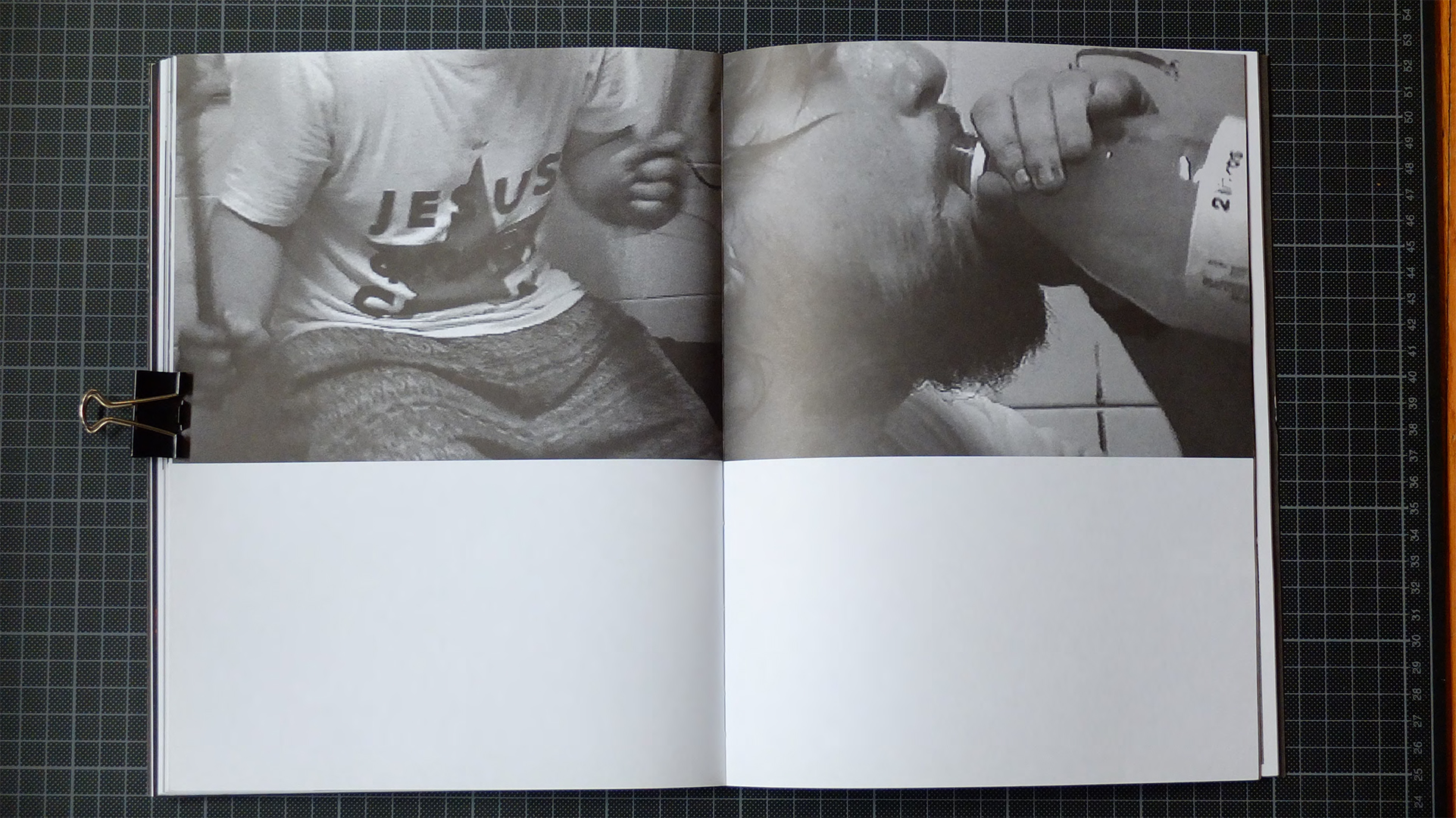

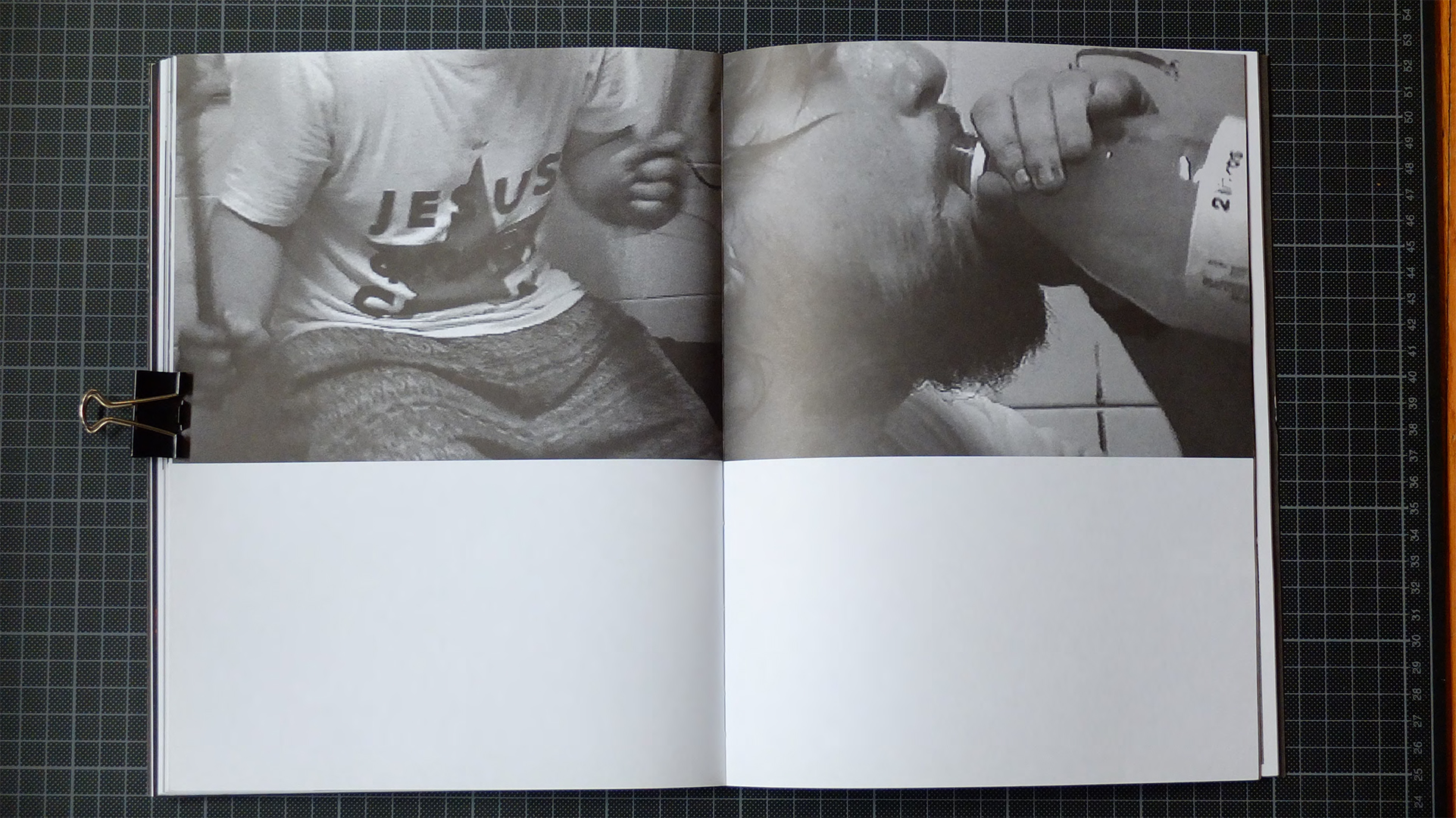

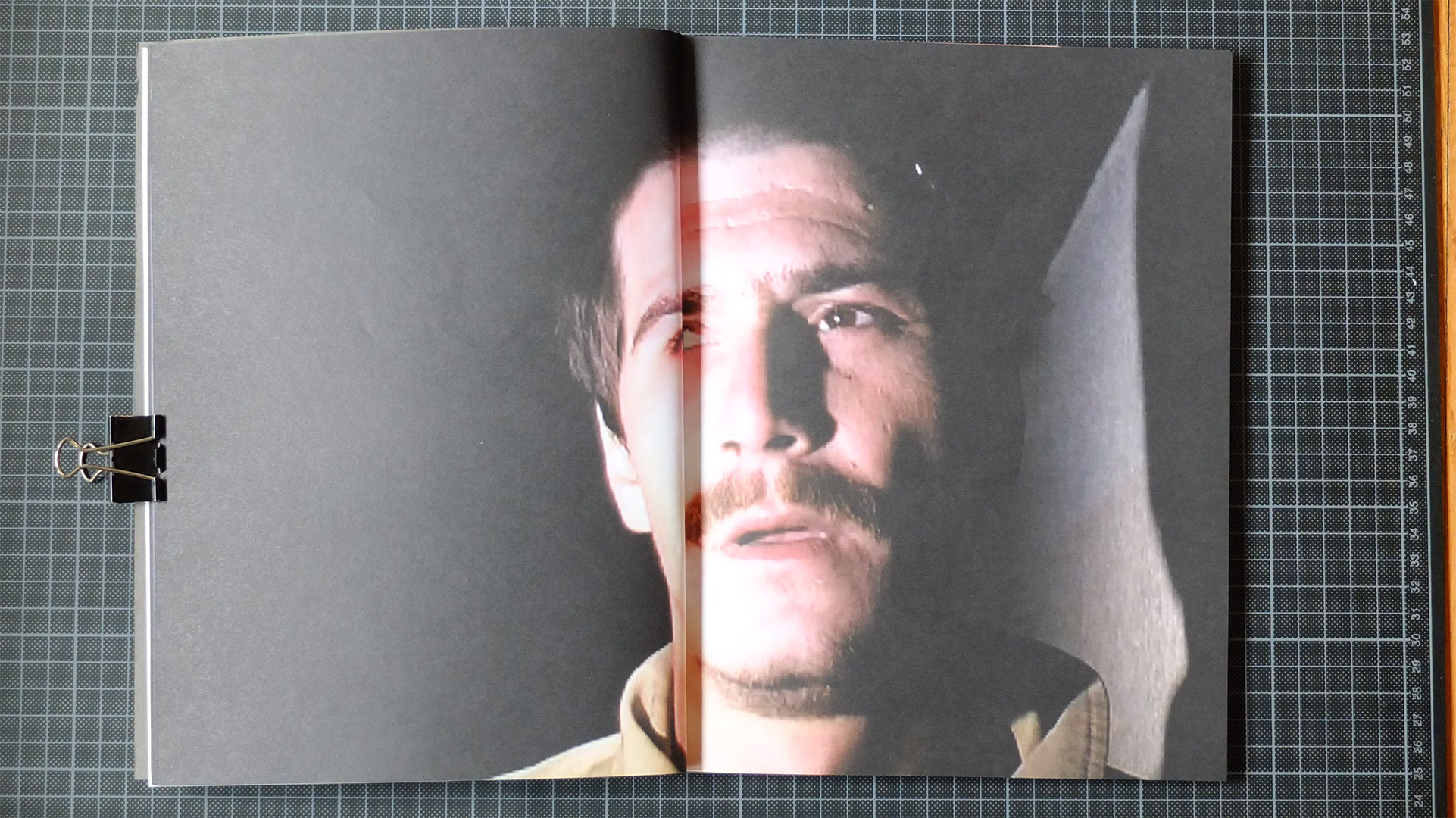

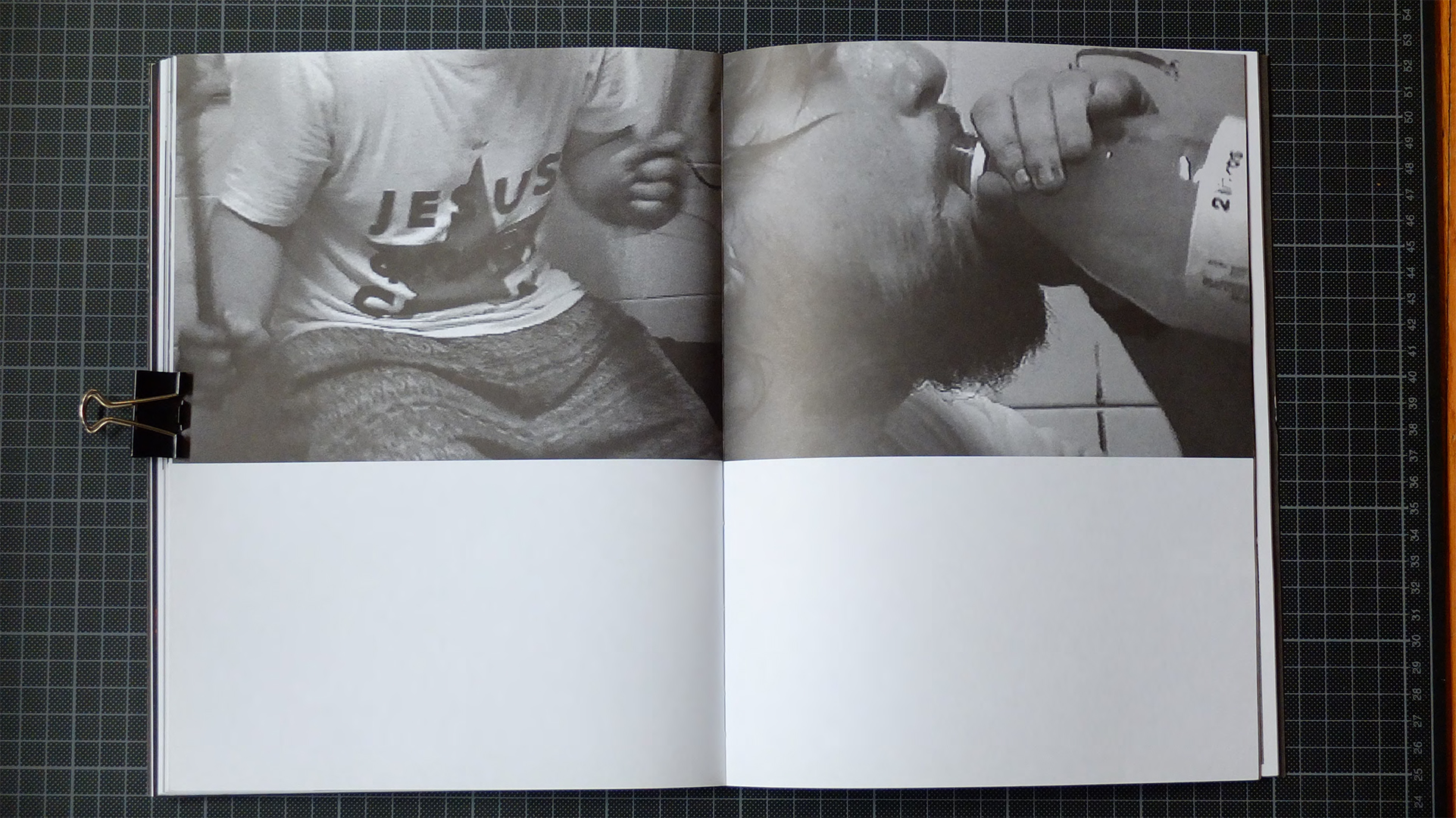

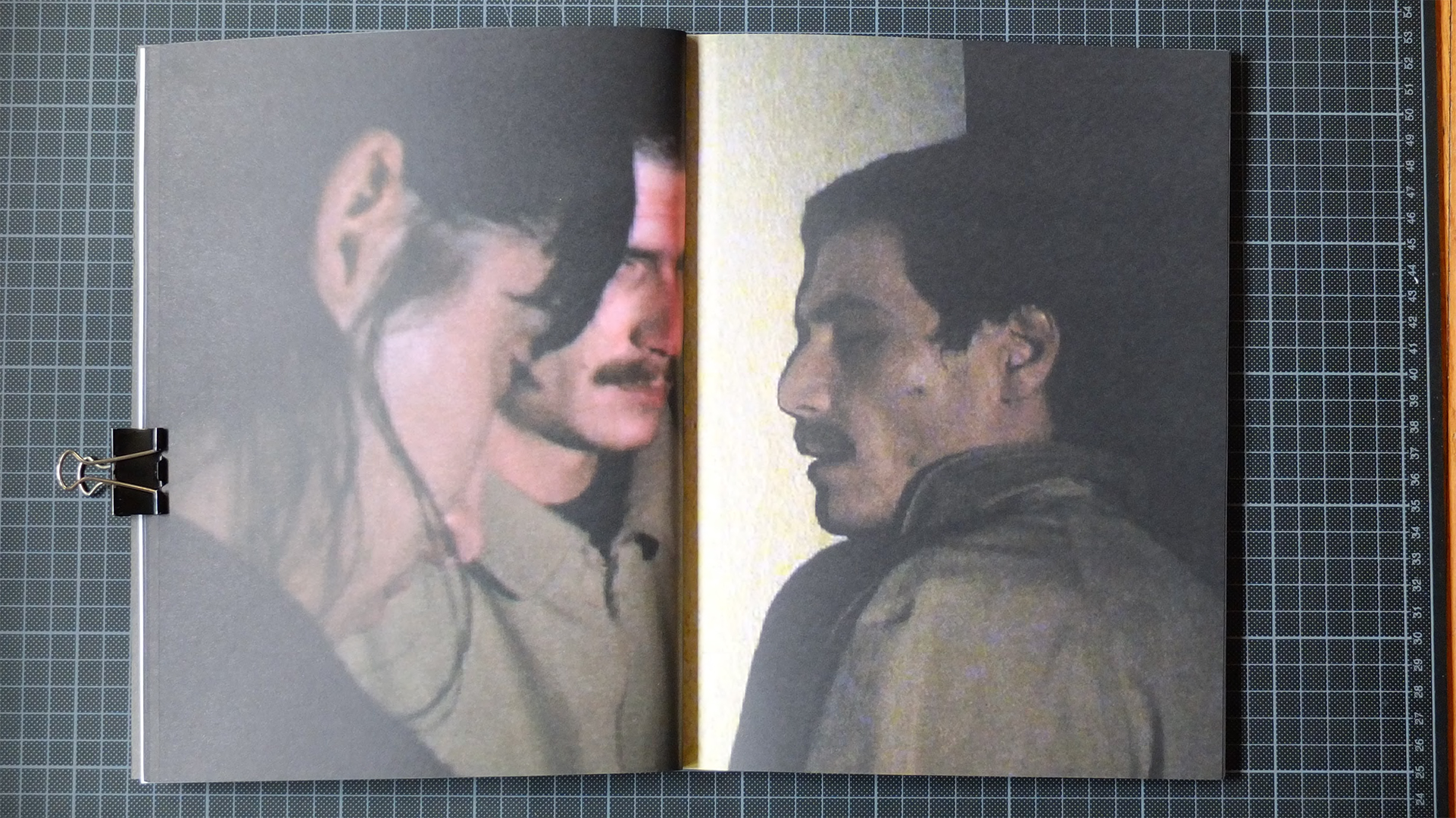

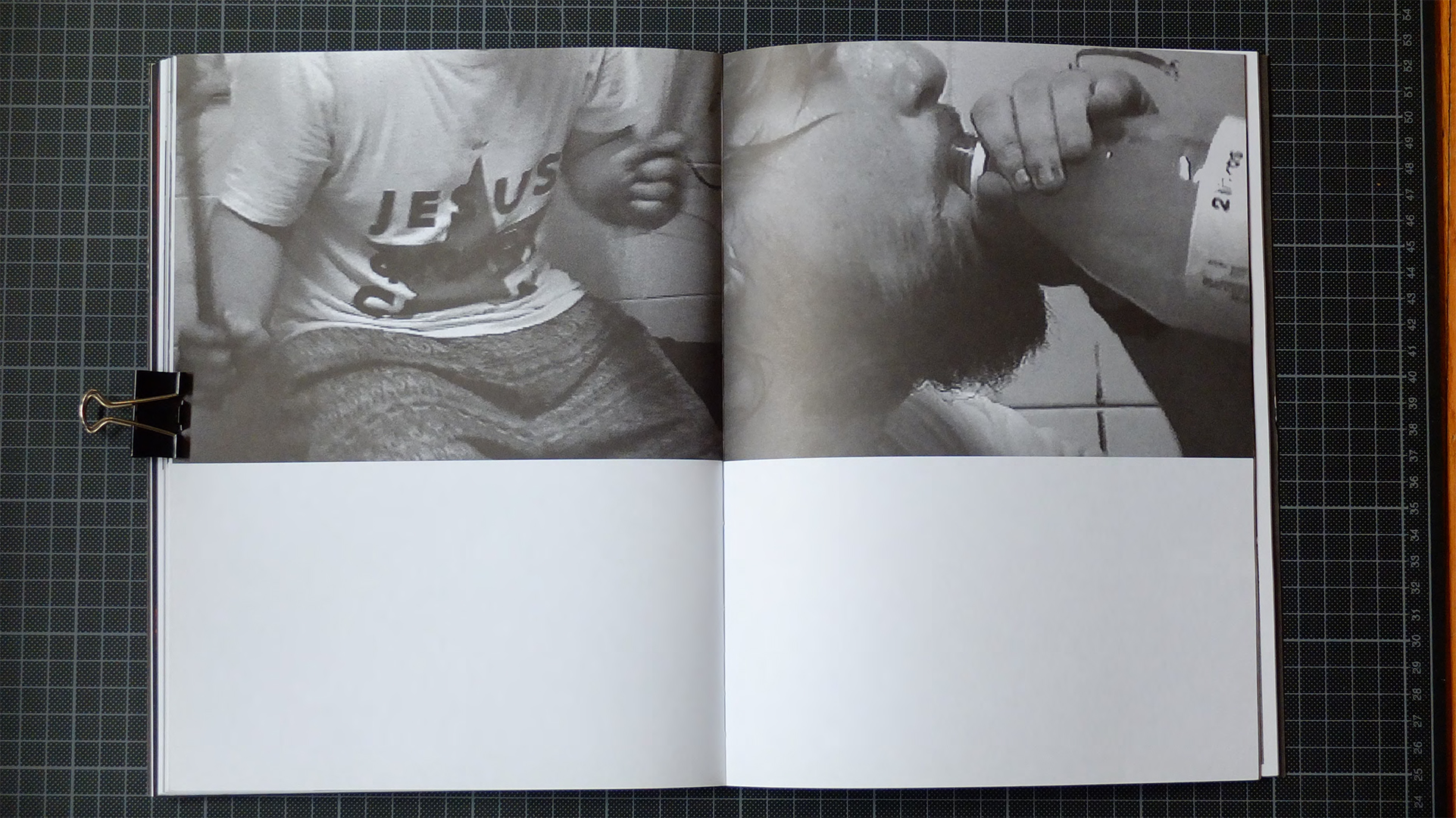

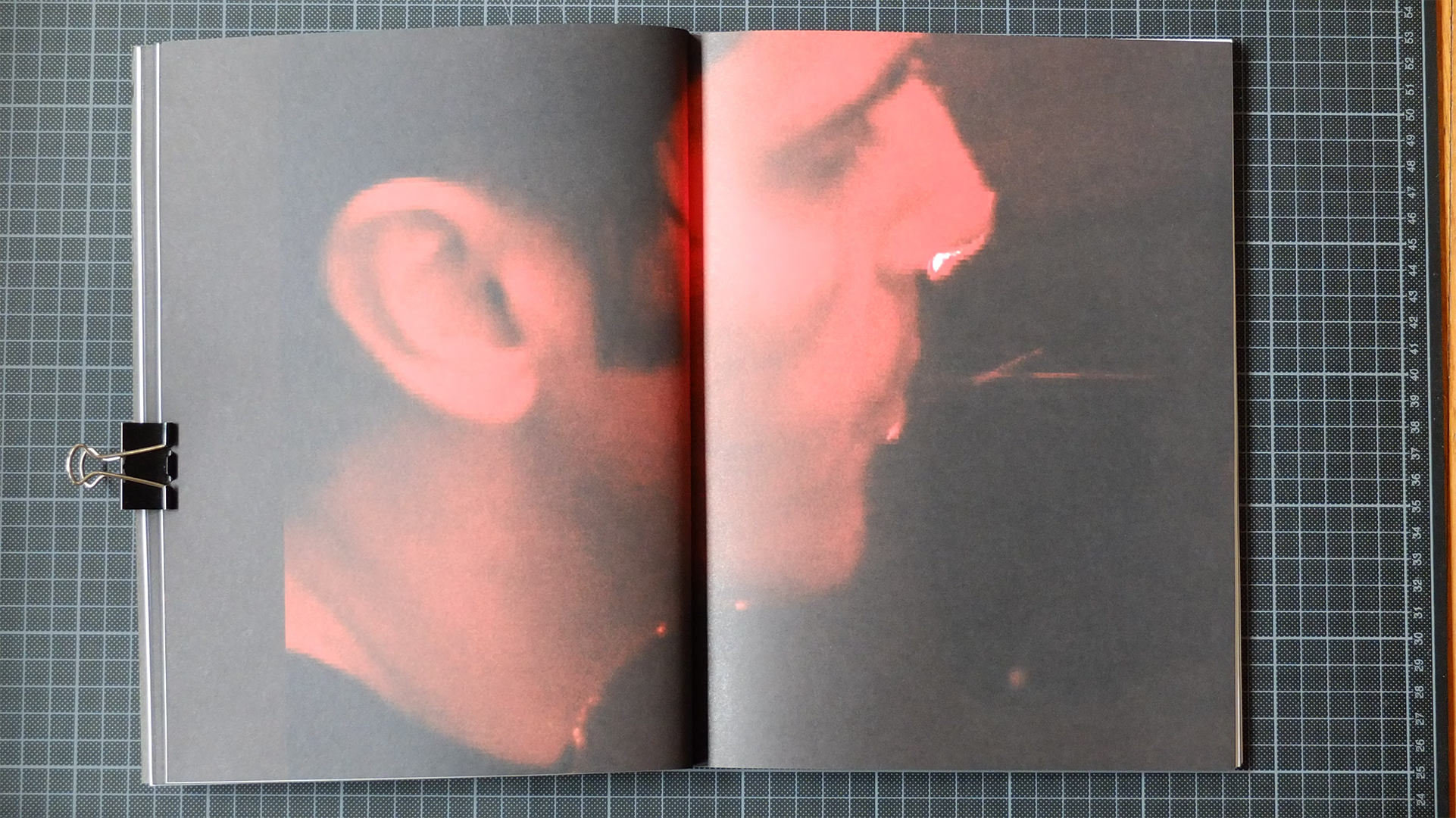

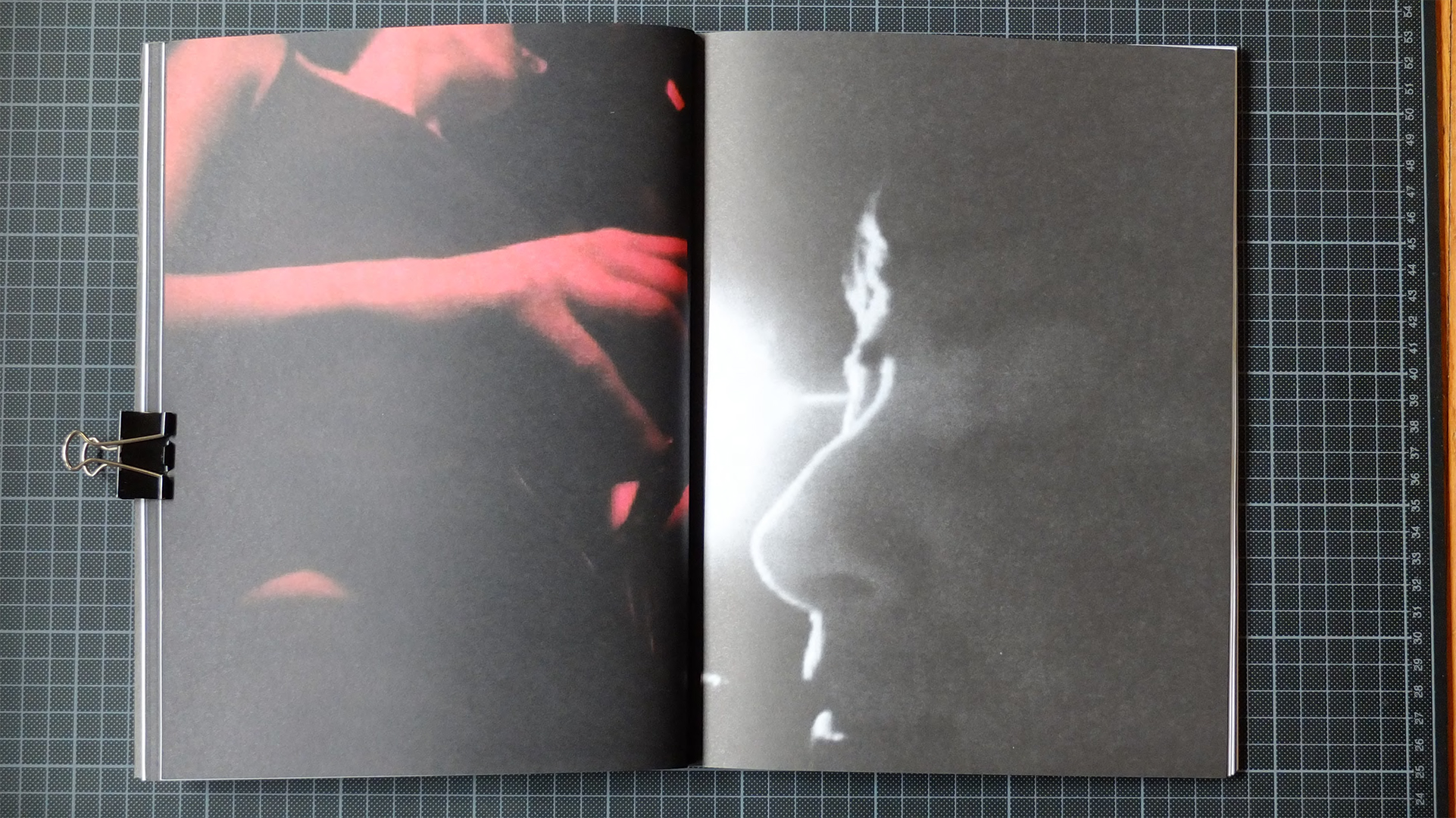

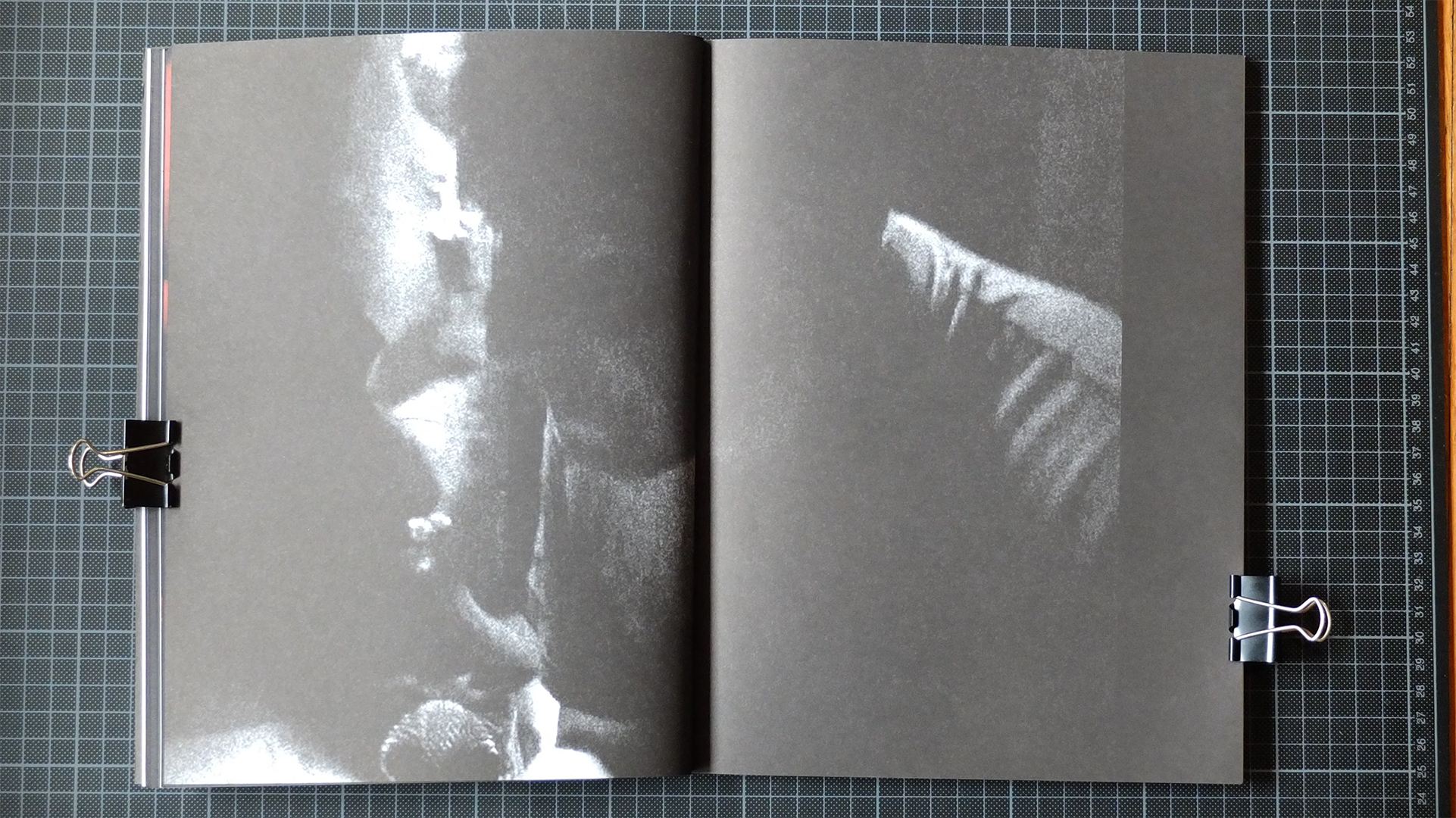

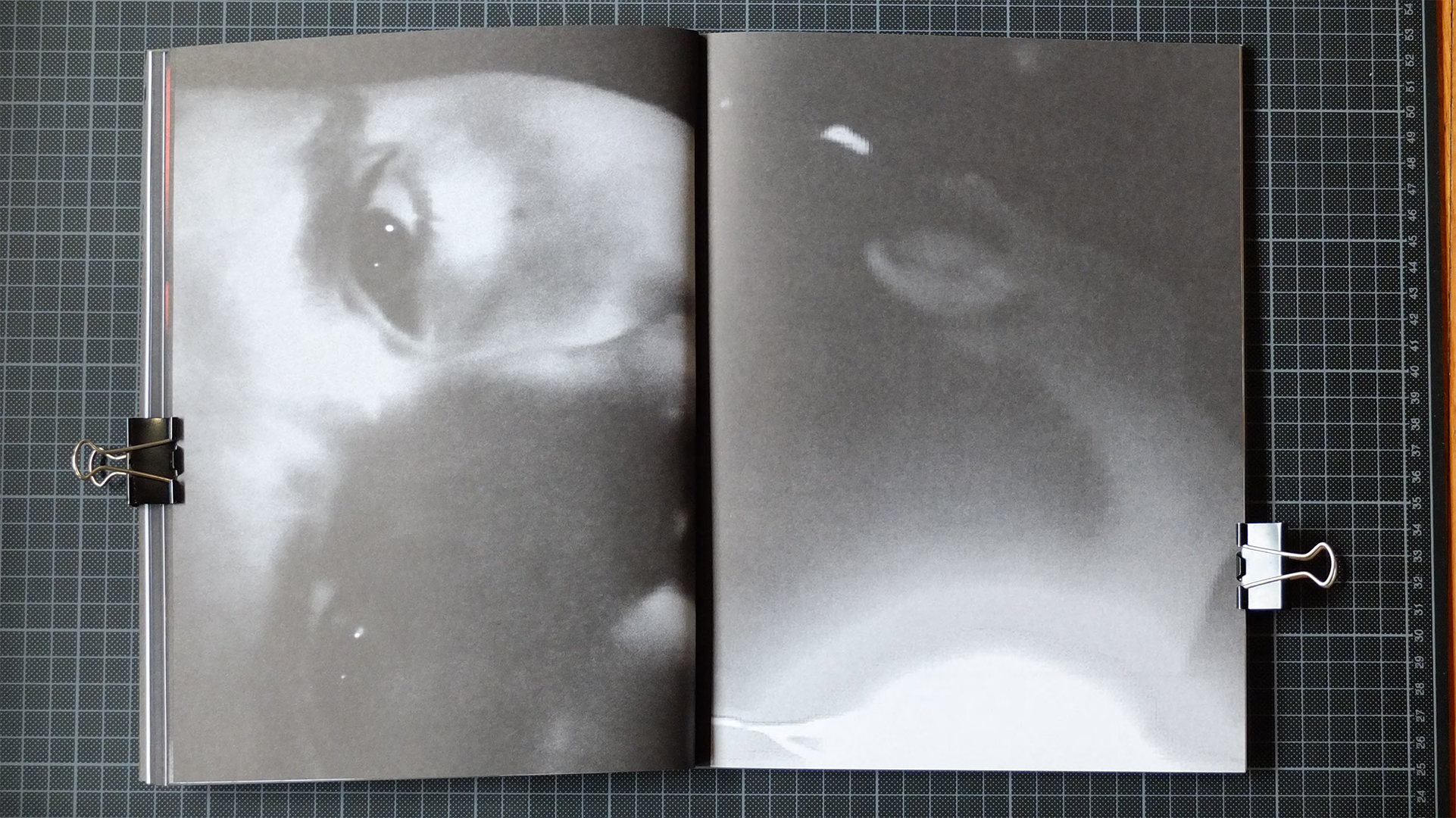

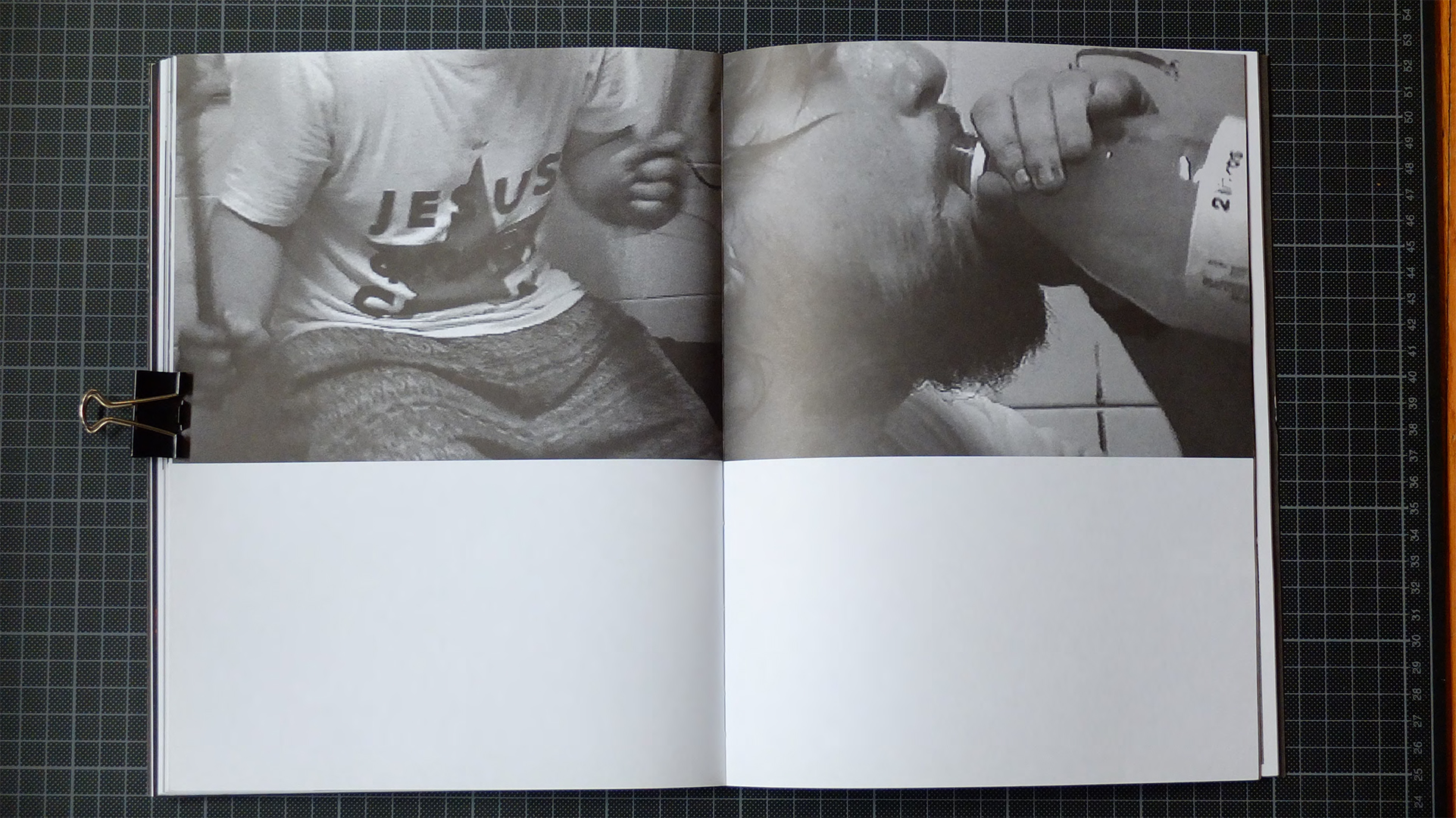

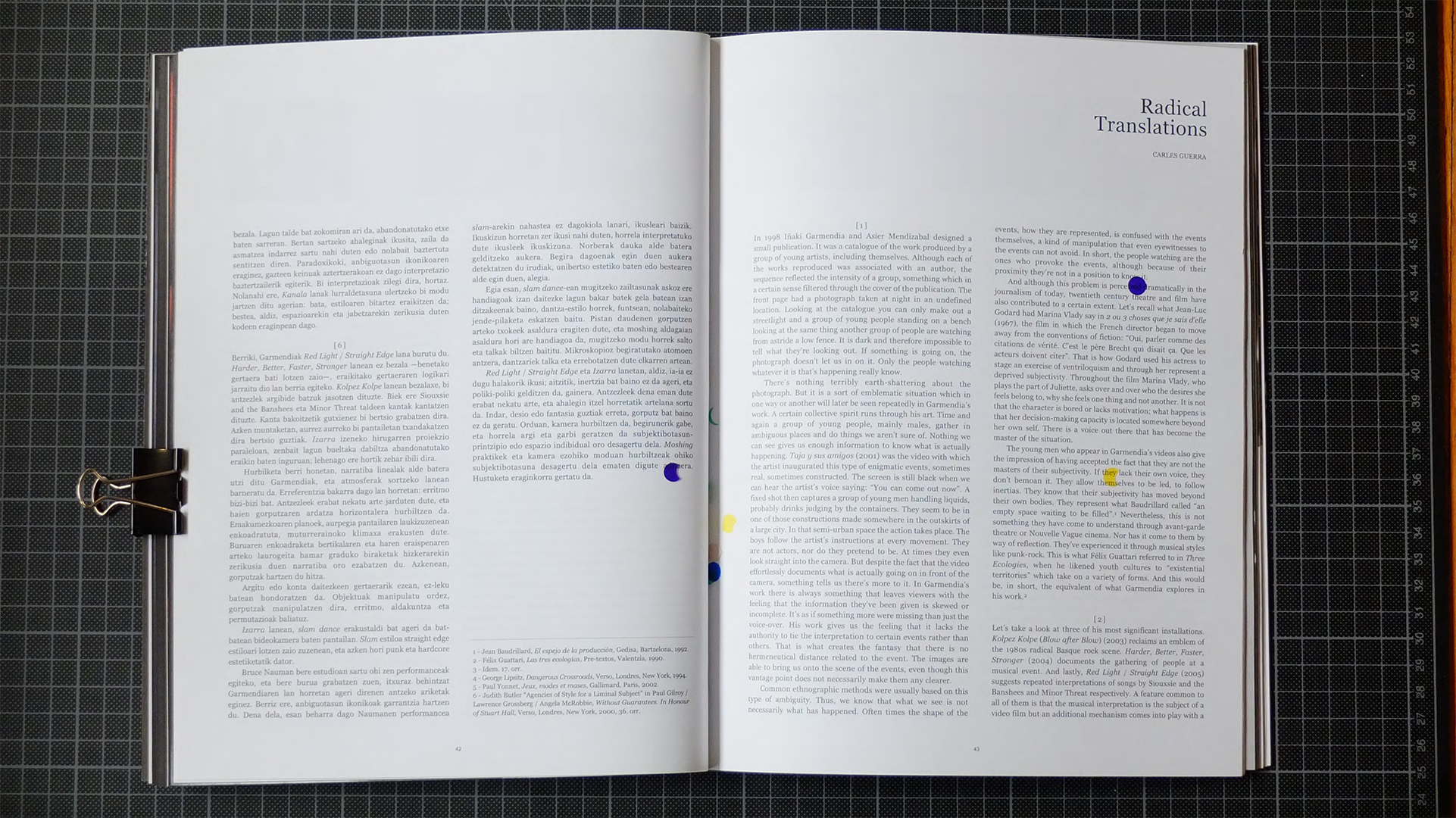

Two studio scenes, confronted once again in a two-channel projection. Two professional lead vocalists (Nadia and Josetxo) attempt to memorise two songs: Red Light by Siouxsie and The Banshees and Straight Edge by Minor Threat. The atmosphere is bathed in red light. The camera, too close to the performers, takes their acting to its limit as it breaks apart the conventional visual grammar of music videos. In this case, the shot-reverse shot has been replaced by a soft montage of two sequences filmed separately. An unexpected way of joining fragments á la Bresson, also a strategy á la Godard; that is, allowing the presence of the non different within the different.

Here, too, sound and image are not always in sync, undoing the submission of images to text within the cinematic narrative. The literalness of the red colour on the bodies is intensified, whilst the rhythmic sound of the photographic camera shutter, together with the electric whipping of the flashing light in the original Siouxsie and The Banshees music video, has been replaced by a silence that strips down this operation of visual transcription. The camera becomes a brazen voyeur on Nadia’s body. Josetxo offers us the text devoid of Barthes’s pleasure, resistance and ritual, as forms of confronting the hierarchical existence of culture.

Related bibliography

Galder Reguera: “Contemporary Art in the Basque Country : Young Basque Art”, Lápiz : Revista Internacional de Arte, Madrid, no. 212, April 2005, p. 46-63.

→ Speaking of others : “Red Light/Straight Edge“; “Izarra”. Frankfurt, Frankfurter Künstverein, 7 June – 13 August 2006.

Iñaki Garmendia : only kids love other kids. [Vitoria] : Basque Government Central Publications Service, 2006.

Catalogue of Iñaki Garmendia’s work published on the occasion of the Basque Government MMIV Gure Artea Awards. Including video stills from Izarra (2005); Red Light/Straight Edge (2005); Goierri Konpeti (2001); Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2004); Kolpez Kolpe (2003-2004); Repeater / Taja y sus amigos (2001); Kanala (1999-2005); Consequence Of You. Videos Cure / Psychic TV (1999); and Carles Guerra’s text ‘Traducciones Radicales’ on the artist’s work, in Spanish, Basque and English [p. 35-46].

Miren Jaio. A Collection of Prints: Visual Arts in the Basque Country. San Sebastian, Etxepare Basque Institute, D. L. 2012.

Iñaki Garmendia. Police/Car. [Press release]. Madrid : Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, 2013.

Efectos de superficie. Iñaki Garmendia y Leire Vergara. [Unpublished interview]. [Bilbao : Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2013].

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

DV PAL (720 x 576)

40’ 58’’

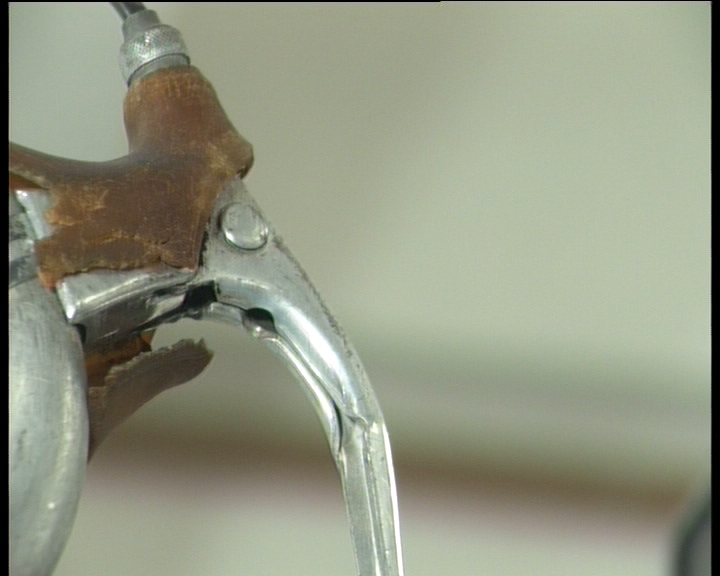

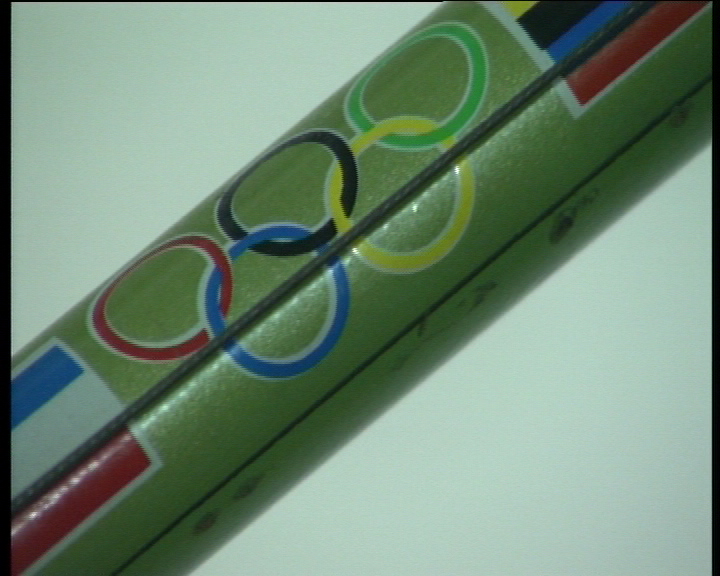

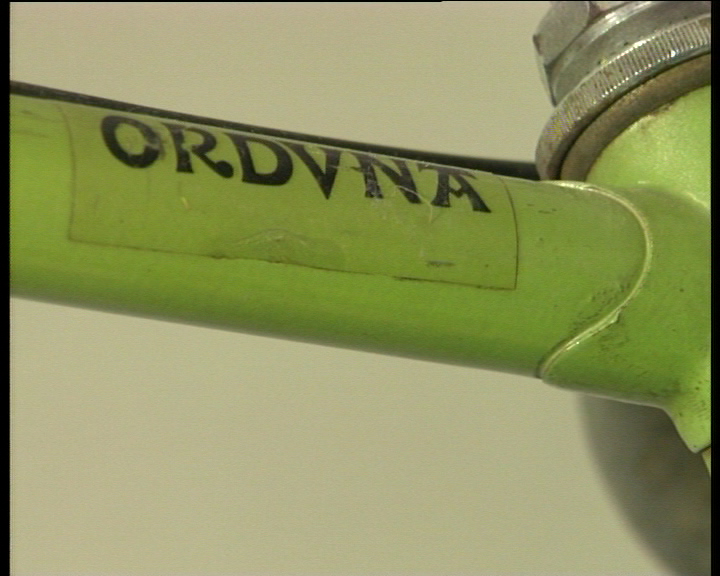

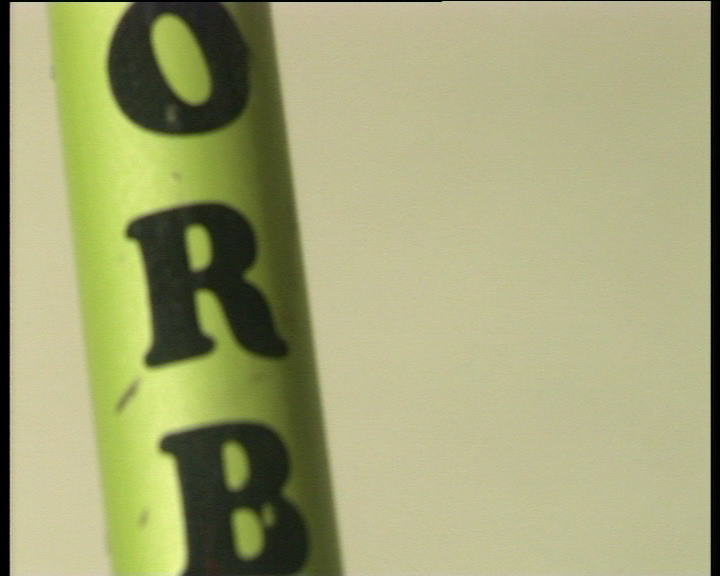

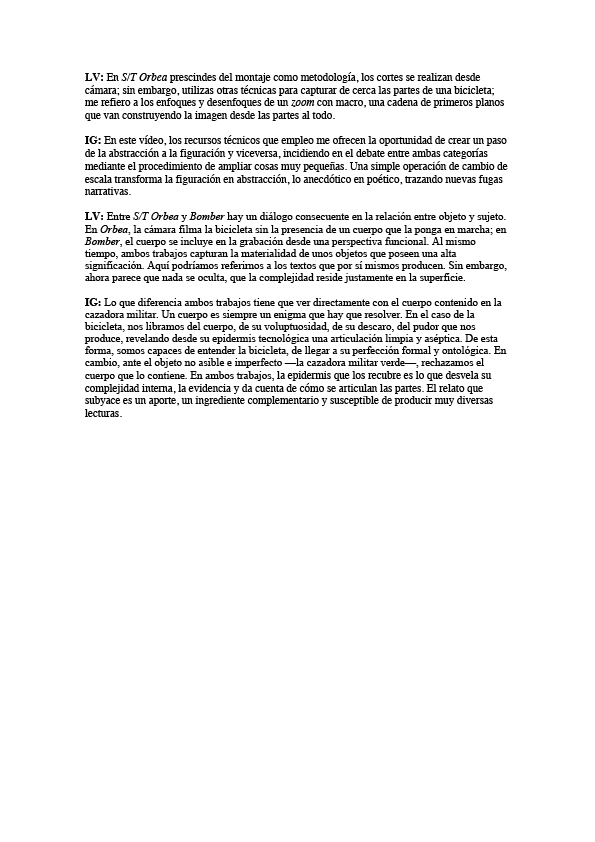

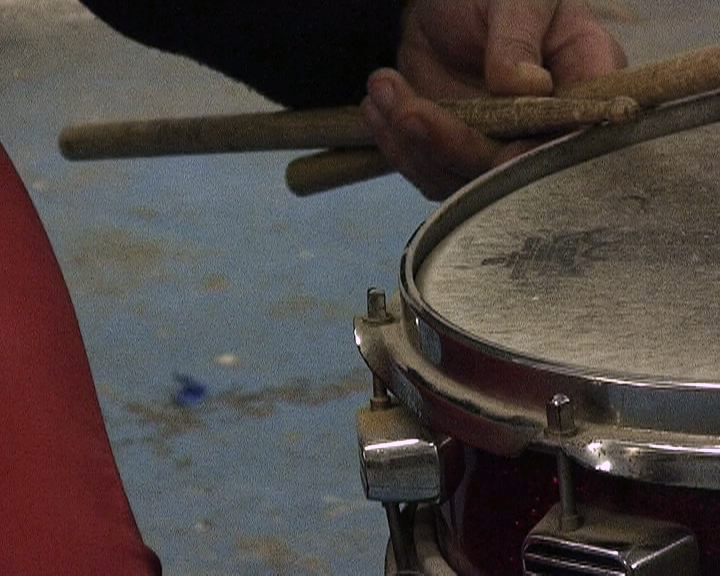

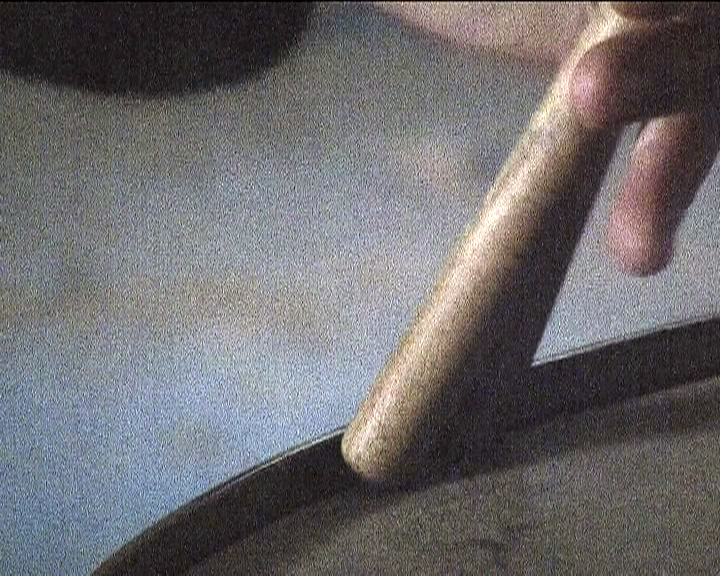

A 40-minute lab video devoted to recording a manufactured object: an Orduña model racing bicycle, produced by the Basque company Orbea during the 70s and 80s. This work explores the specificity of the object by applying a structural, let’s call it materialistic, type of approach. The process avoids a narrative, focusing instead on using the technical features of the camera, which transforms the filming into a formal operation. For this, the artist uses a macro lens. Through it he reduces the distance to the object examined to a minimum, creating a dialogue between its presence, the time of its filmic exposure and the moving image. The latter moves forward down a chain of sequences in which parts of the bicycle occupy almost the entire frame, which grants it certain monumentality. A long series of close-ups carefully studies every detail before drawing away to reveal the whole in some wider shots. The image fluctuates between the abstract and the figurative.

In S/T Orbea the historical narrative has no place, there is only room for the phenomenological aspects produced in the encounter with the object. The sound contributes to this reverie effect. Lacking space for external narratives, image destroys the possibility of text. The camera recreates the pleasure produced by gazing at the assembly of the elements that make up the nature of this technological object.

Related bibliography

→ Iñaki Garmendia : katakrak. Barcelona, Virreina Centre de la Imatge, 14 July – 2 October 2011.

KATAKRAK: Iñaki Garmendia. [Exh. cat.]. Barcelona: Barcelona City Council, Institut de Cultura, 2011.

Catalogue of solo exhibition at Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, titled Katakrak (14/07-02/10/2011) including “Metraje”, a text by Peio Aguirre, in Spanish, Catalan and English. The text basis its analysis of the artists work on videos such as S.T. (Orbea) (Orduña) (2007), Bolueta (2011), Kolpez Kolpe (2003), Harder, Faster, Better, Stronger (2004), and series such as Txitxarro (2000). With black and white images and brief artist bio.

→ Materiality [Alternativa 2012 : International Visual Arts Festival]. Gdansk, Hall 90B, 25 May – 30 September 2012.

Materialnosc = Materiality. [Exh. Cat – CD(.pdf)]. [Gdansk], 2012, p. 3, 5, 47, 125.

Bilingual Polish/English catalogue for Materiality, Hall 90B de Gdansk (Polonia) (25/05-30/09/2012) part of the Alternativa 2012 cycle of exhibitions, curated by Aneta Szylak, Arne Hendriks, Inés Moreira and Leire Vergara, including around 30 international artists. Includes exhibition map, introductions by curators and images of Garmendia’s video S.T. Orbea (2007), claiming that “The work explores the specifity of the object following a rather structural/materials approach of recording, so to say, a process in which narrative is avoided and the usage of the camera becomes a formal operation” [p. 47]. Also including brief artist bio [p. 125].

ARCOmadrid 2013: International Contemporary Art Fair. Madrid: ARCO/ IFEMA, Feria de Madrid, cop. 2013, p. 222.

→ Garmendia, Maneros Zabala, Salaberria : proceso y método. Bilbao, Guggenheim Bilbao, 31 October 2013 – 16 February 2014.

Efectos de superficie. Iñaki Garmendia y Leire Vergara. [Unpublished interview]. [Bilbao : Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2013].

Unpublished dialogue between Leire Vergara and Iñaki Garmendia for Garmendia. Maneros Zabala. Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Bilbao (31/10/2013-16/02/2014). The artist answers questions on his work process, the importance of the script, interrelationships between different works, text/image correspondence, and tensions between subject and object.

→ Después del 68 : arte y prácticas artísticas en el País Vasco, 1968-2018. Bilbao, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 7 November 2018 – 28 April 2019.

Después del 68 : arte y prácticas artísticas en el País Vasco, 1968-2018. [Exh. cat.]. Bilbao : Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 2018, pp. 103, 115, 116, 231, 281.

Exhibition catalogue for Después del 68, Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (7/11/2018-28/04/2019), a revision of art practices in the Basque Country over the past 50 years via a selection of approximately 150 pieces, curated Miguel Zugaza, Miriam Alzuri and Begoña González. Includes still from Garmendia’s S.T. Orbea (2007), one of the selected works [p. 231]. Kolpez kolpe (2002-2003) is cited, with image, in Peio Aguirre’s article “Periodizando los años noventa. Sujetos deseantes” [p. 103]; and Miren Jaio, in the chapter “Desde aquí hasta el fin del mundo. 2008-2018” speaks of Garmendia’s exhibition Katakrak, Palacio de la Virreina, Barcelona (2011), and includes a view of the works Líneas de montaña (I-IV) and Sin título (verja) [pp. 115-116]. The cover of the exhibition catalogue for Garmendia; Maneros Zabala; Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (2013) is also reproduced [p. 281]. A chronology by Mikel Onandia includes references to Garmendia’s principal exhibitions and projects [pp. 400, 421, 428, 440, 443, 445, 451, 465, 469, 472, 476, 478, 479, 481, 482, 483, 487, 499, 503 y 505].

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

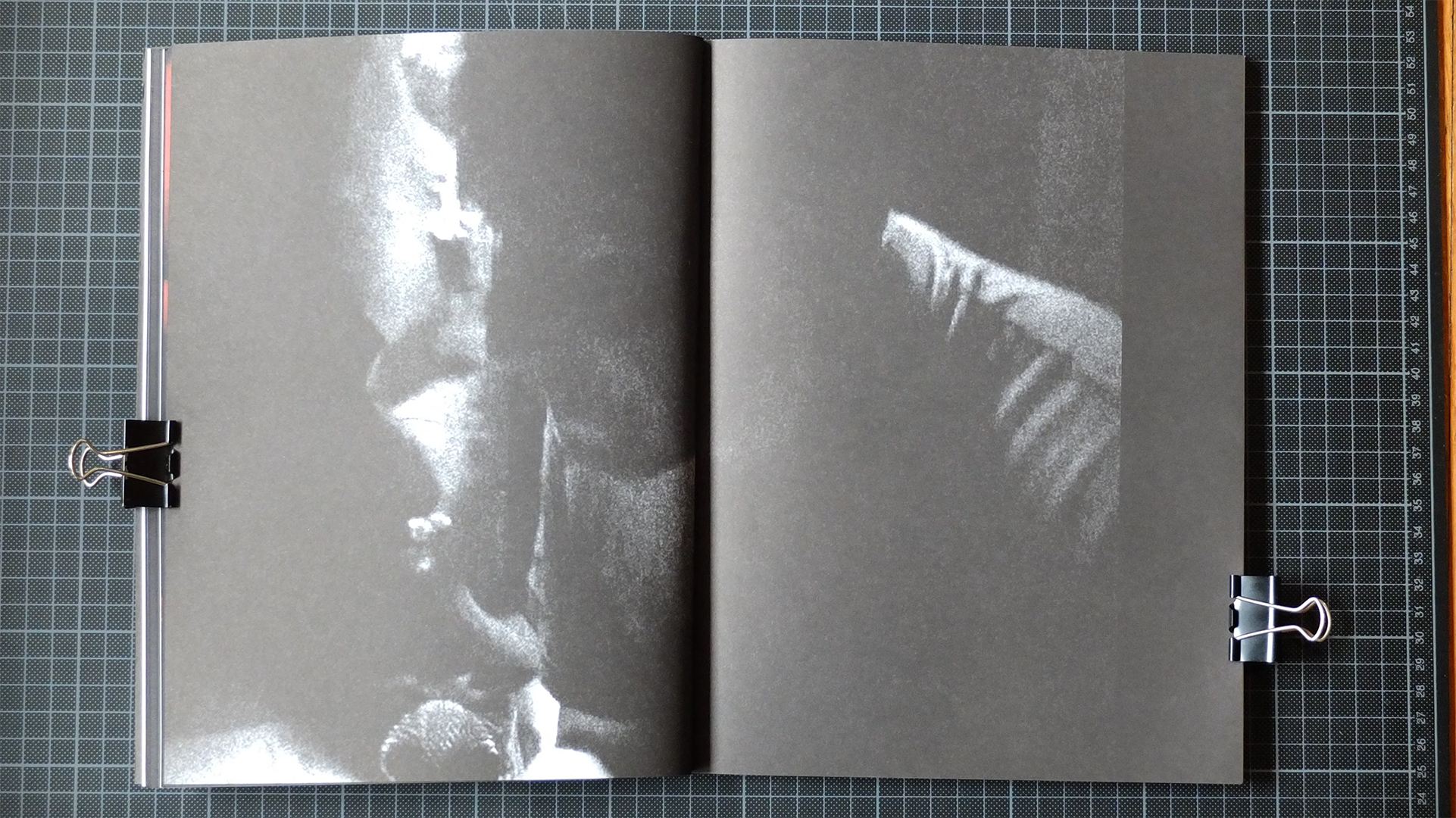

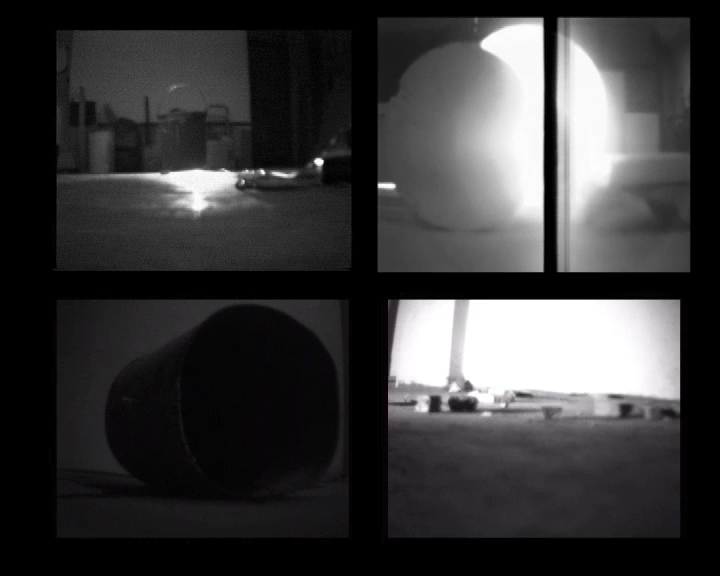

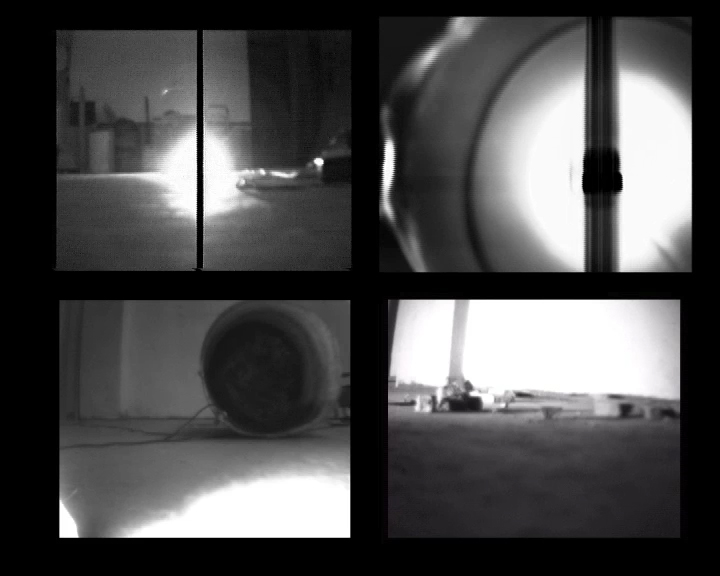

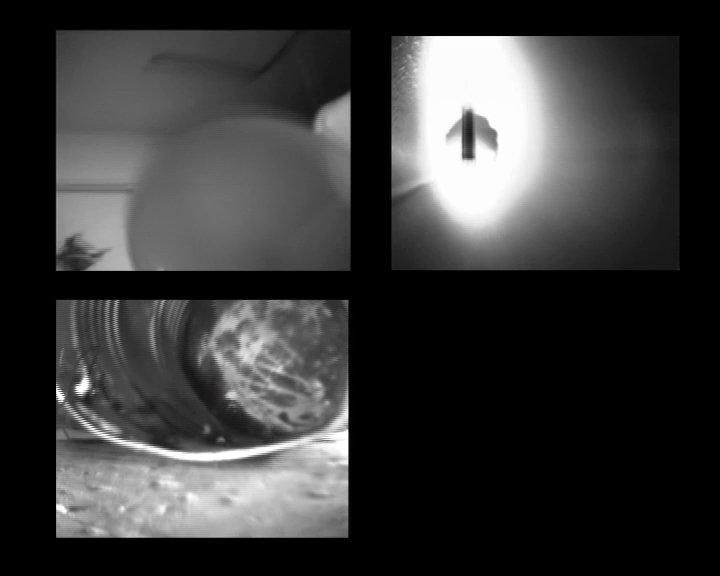

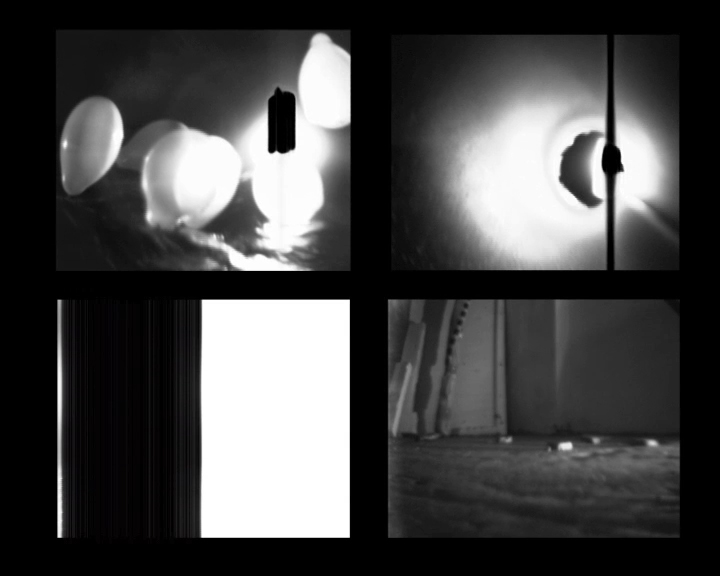

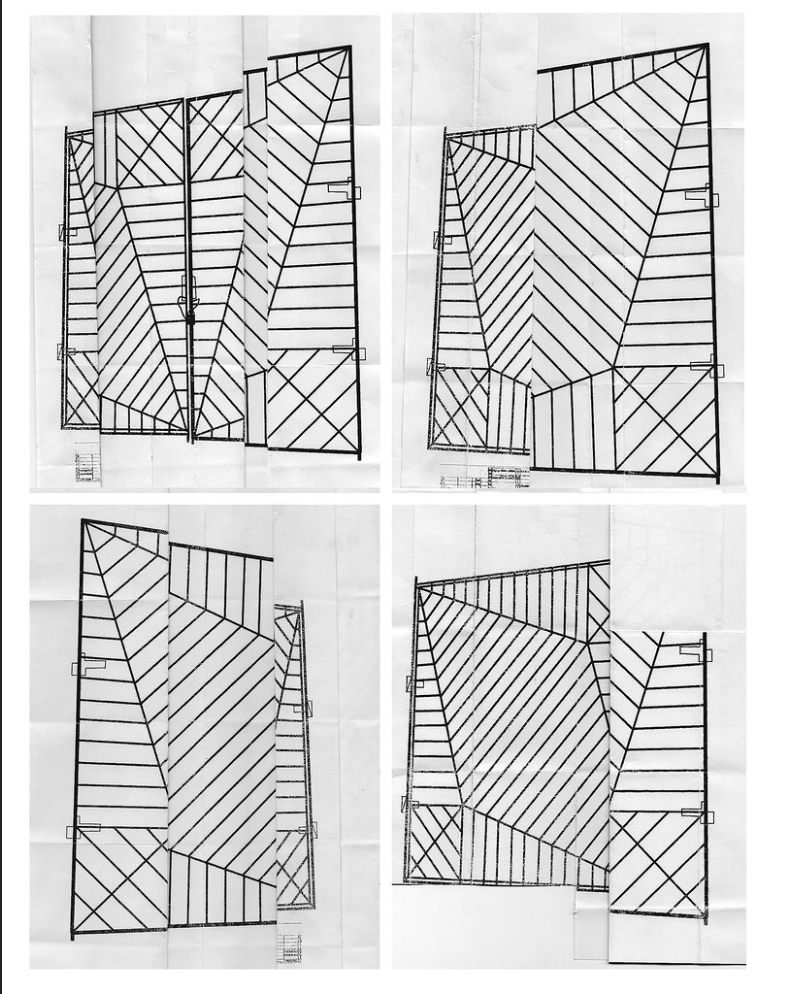

Four-channel video, with sound, colour

5'58''

DV PAL (720 x 576)

A series of lab videos make up this four channel work produced in a studio setting in which certain objects are the protagonists. These “black videos”, as the artist also calls them, were recorded with a Tyco toy camera purchased in 1997. The use of this camera in this context can be read as a reference to the faktura of films (such as Living Inside, 1989, or If Every Girl Had a Diary, 1990) shot by Sadie Benning with a Fisher Price PXL-2000 camera that her father, James Benning, gave her as a Christmas present when she was 15 years old. Unlike the Fisher Price camera, the Tyco does not use tape, and therefore Iñaki uses a beta video recorder to preserve footage. The editing takes place, once again, during the recording, by using the camera’s on/off button.

The coarse texture of the black and white image in Sadie’s and Iñaki’s videos accounts for an exploration via the medium of film that emerges from the intersection between narrative experimentation, performance, and cinematic syntax. The Tyco records image only, lacking a microphone. During the filming the same jack plug is used for the video and audio inputs, which produces a series of sonic interferences as the camera moves. The sound generated comes from the feedback at its contact with different elements. The camera functions as an electric guitar, albeit a soundless one. On the other hand, the capture of light is also restricted, since its performance is limited in terms of how it responds to darkness or to an excess of light, generating a visual error that translates as the appearance of a black band. Finally, the result is a sort of haphazard composition between sound, image, and the elements.

The first video in the series, 99 Red Love Balloons, was exhibited integrally on a monitor in the exhibition 1, 2, 3… Vanguardias: Cine/arte entre el experimento y el archivo curated by Łukasz Ronduda, Florian Zeyfang and myself at Sala Rekalde in 2007-2008. Almost simultaneously, NO R.S. (99 Red Love Balloons) was presented as a complete series in 2008 at Moisés Pérez de Albéniz Gallery (Pamplona). In the catalogue for the exhibition 1, 2, 3… Vanguardias, Iñaki intervened on the pages with images taken from the recording and also from a perforated photocopy containing Robert Morris’s text “A Method for Sorting Cows” (1967), a scanned image showing also its own faktura, originated in this case in the wear due to the use of this studio document. The reference to Morris’s piece, a set of instructions for an impossible action, offers points of connection with the epic tension of Iñaki’s videos as they attempt to capture a sublime image produced by the balloons bursting. However, as the title suggests, these blasts are not comparable to the explosions shot by Roman Signer.

Related bibliography

→ NO R.S. Iruña/Pamplona, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, January – February 2008.

Iñaki Arzoz. “Iñaki Garmendia, en Iruñea : en el límite”, Mugalari, Gara, San Sebastian, 16/02/2008, p. 10.

Rosa Olivares (ed.). 100 Spanish artists. Madrid, Exit Publicaciones, 2008, pp. 184; 447.

→ Garmendia, Maneros Zabala, Salaberria : proceso y método. Bilbao, Guggenheim Bilbao, 31 October 2013 – 16 February 2014.

Garmendia, Maneros Zabala, Salaberria: proceso y método = process and method. [Exh. cat.]. Bilbao: Guggenheim Bilbao, 2013, pp. 16; 28; 120; 126.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

25’18’’

HD Video (1920 x 1080)

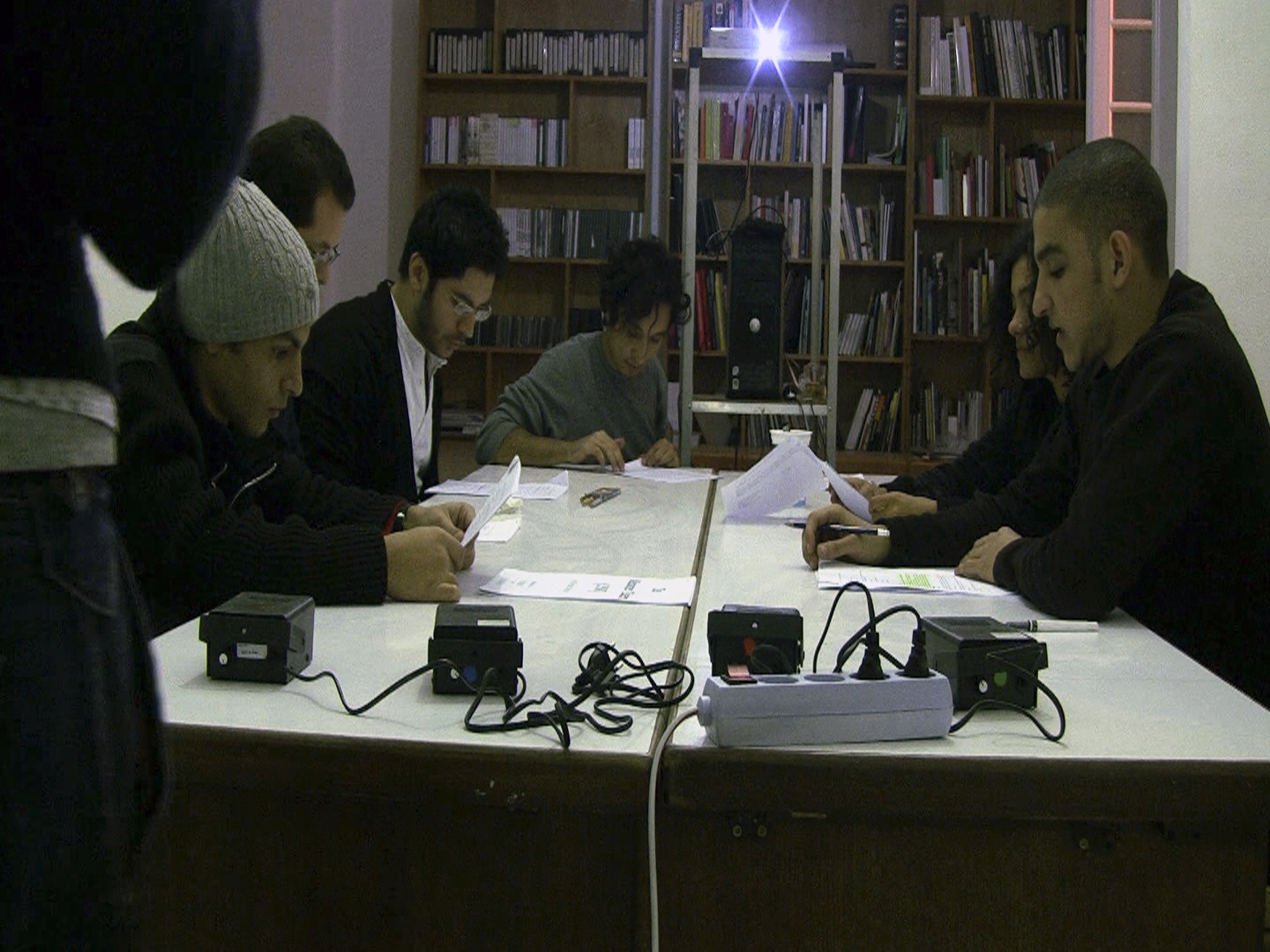

Cairo, 2011. This timely video was recorded in the C.I.C. (Contemporary Image Collective) Library a week before the Youth Revolution —also referred to as the White Revolution—. CCC/MT is structured as a script-performance using parts from the prologues to two plays by Bertolt Brecht: The Caucasian Chalk Circle, an epic written between 1944 and 1945, during the author’s exile in the United States, and The Measures Taken, a didactic piece written between 1929 and 1930.

This piece confronts us, once again, with the dual relationship between two artefacts that were not necessarily previously related. In this case, the artefacts are prologues to two plays written by the same author, but very distant in time. The preface to a play normally offers context, displaying the author’s position and the text’s didactic intentions. At times, it filters other, more mundane references, which have the ultimate effect of provoking life to break in, affecting the reception of the art form. In this work by Iñaki it is not possible to neutralise the interruption of art by life, nor to identify the assertive Bretch from the doubtful one, the young convinced Bretch from the acclaimed one who doubts himself.

A group of six young people, with Arab as their mother tongue, read aloud the prologues to the aforementioned plays in English. The reading flows as a didactic process of internalisation, in which misunderstandings and spelling mistakes occur. Time functions as a material condition of production, undoing this incorporation process. On one hand, the chronology is inverted: CCC is presented before MT —a work published over a decade earlier. On the other, the action also flows backwards, since the texts are increasingly reduced with each reading, constantly becoming simpler until they lose their meaning, thus slowly complicating the internalisation process. The reading is broken down further with each take. Witnessing this disintegration, we clearly sense a circular timeline. The action seems depleted within this circularity. The city, the traffic, the sirens ring repetitively in the background from the beginning of the recording. Towards the end of the video, the dynamic sound of the street deafens this feeling of exhaustion.

Related bibliography

→ Garmendia, Maneros Zabala, Salaberria : proceso y método. Bilbao, Guggenheim Bilbao, 31 October 2013 – 16 February 2014.

Exhibition images courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao.

Pablo Marte. «Sector Conflictivo. #02: Iñaki Garmendia», Basilika. Podcast, 85 min. 31 sec.

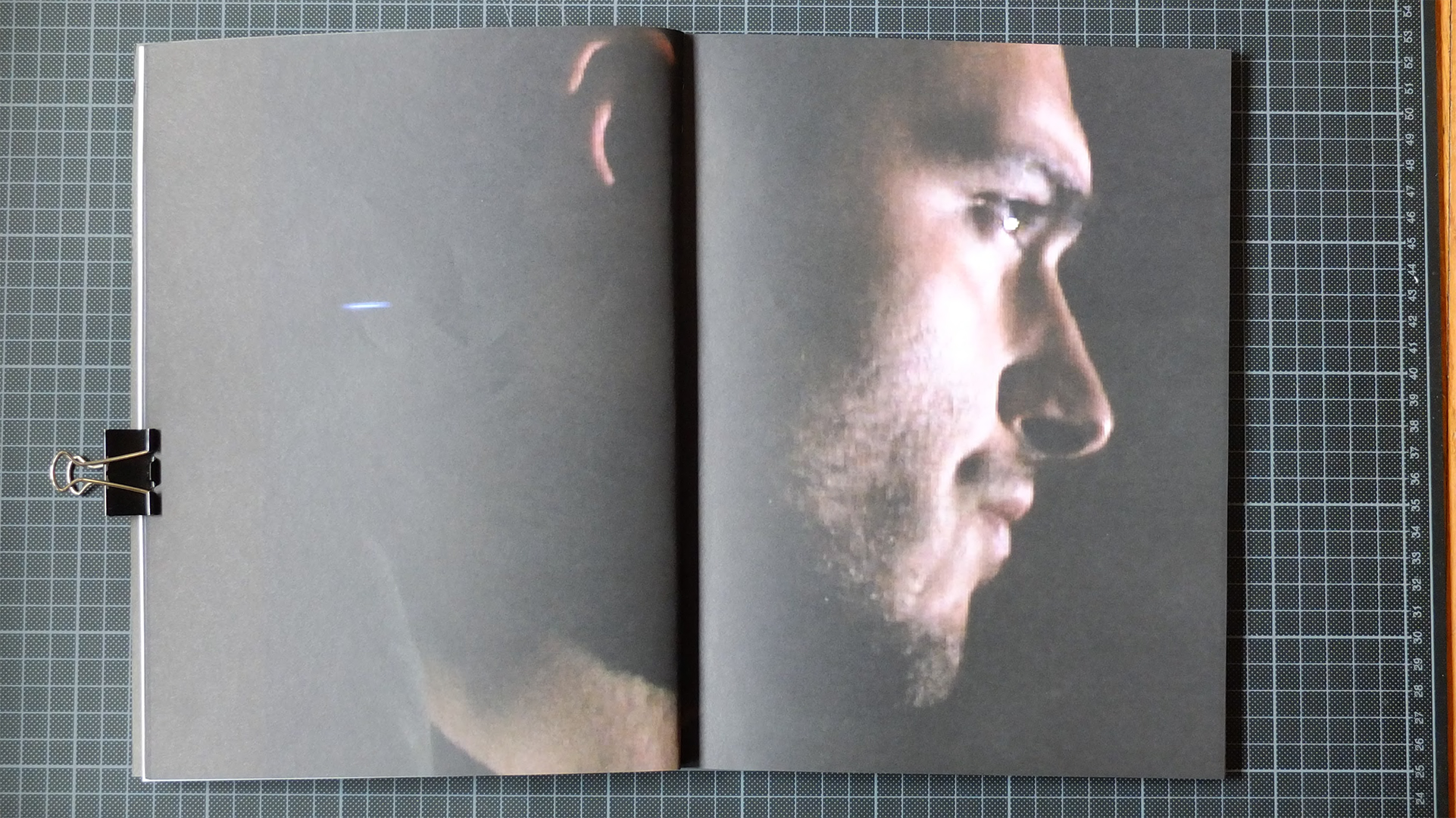

Two-channel video, with sound, colour

24’20’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

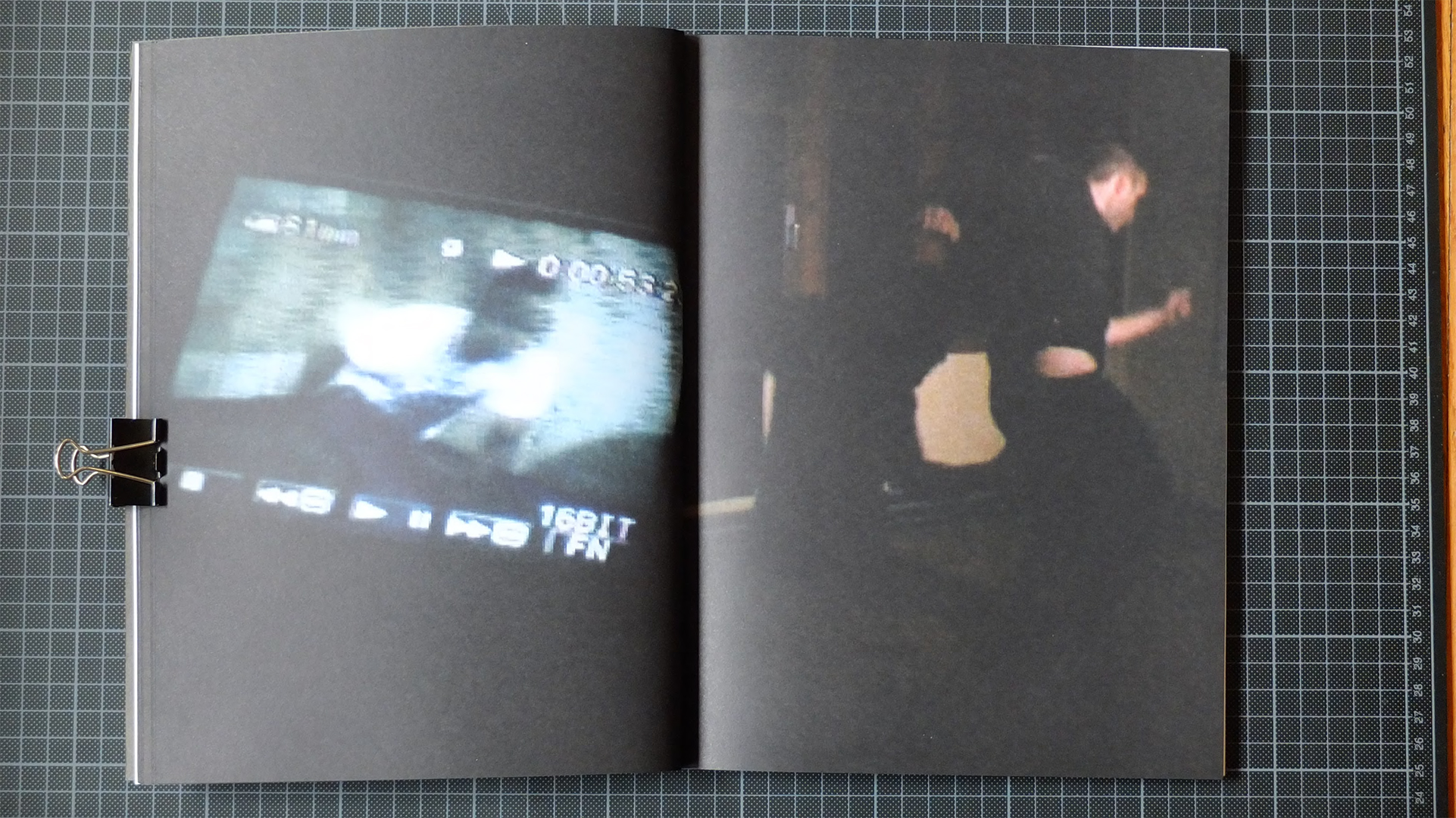

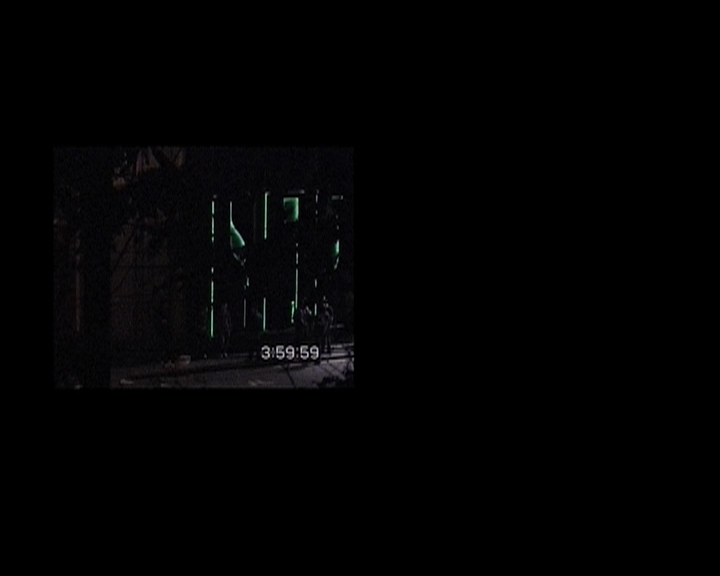

Bolueta. A two-channel nighttime video. A field recording made up of footage simultaneously captured by two cameras that record the events unfolding in a specific area; namely, the entrance to a renowned Bilbao night club. A time sequence, from 4:00 to 4:55 AM, marked by the camera counter visible on the lower-right corner in the projection on the left-hand side. As the footage plays out, we realise that the action portrayed does not match the time on video, having been altered by almost imperceptible cuts that ultimately reduce it by half. This structural form warns us about the representational frame to which we are subjected as voyeur-spectators; meaning, that the anthropological quality of the recording device is not offered as a means to posit any kind of truth. On the contrary—all the elements that make up the device indicate that the images actually seek to bind us in the rules of a whimsical game of tag.

Bolueta/. Both cameras are concealed far from where the action takes place, as if they wanted to protect themselves with the maximum possible distance for a better extraction. One of the cameras, a High 8, shows the time and a series of grainy zoom-ins. The texture of the captured portraits is analogic. The other camera, which is digital, can be more precise in accessing the target; however, its sharpness seems more artificial, due perhaps to its colour saturation. We are introduced to two recent recording methods from different time contexts and which are now exhibited in comparison, as if they were the remains of a nascent visual archaeology. Led by a homoerotic gaze, a game takes place between the images, recruiting involuntary actors as it unfolds, take after take.

Bolueta/Front 242. The night club’s electronic music bathes the images in the background as the night draws on. The music sounds more like prerecorded noise, an effect caused by the distance at which the cameras are placed.The sound distancing makes the music work as a sort of quotation over the images, revealing once again the collective construction of subculture as a possible act of ambiguous resistance. Nevertheless, we are hardly able to build a new mythological style out of the digital faktura of the images of the present; their nature navigates instead within an order of rejection/assimilation.

Related bibliography

KATAKRAK: Iñaki Garmendia. [Exh. cat.]. Barcelona: Barcelona City Council, Institut de Cultura, 2011.

Catalogue of solo exhibition at Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, titled Katakrak (14/07-02/10/2011) including “Metraje”, a text by Peio Aguirre, in Spanish, Catalan and English. The text basis its analysis of the artists work on videos such as S.T. (Orbea) (Orduña) (2007), Bolueta (2011), Kolpez Kolpe (2003), Harder, Faster, Better, Stronger (2004), and series such as Txitxarro (2000). With black and white images and brief artist bio.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

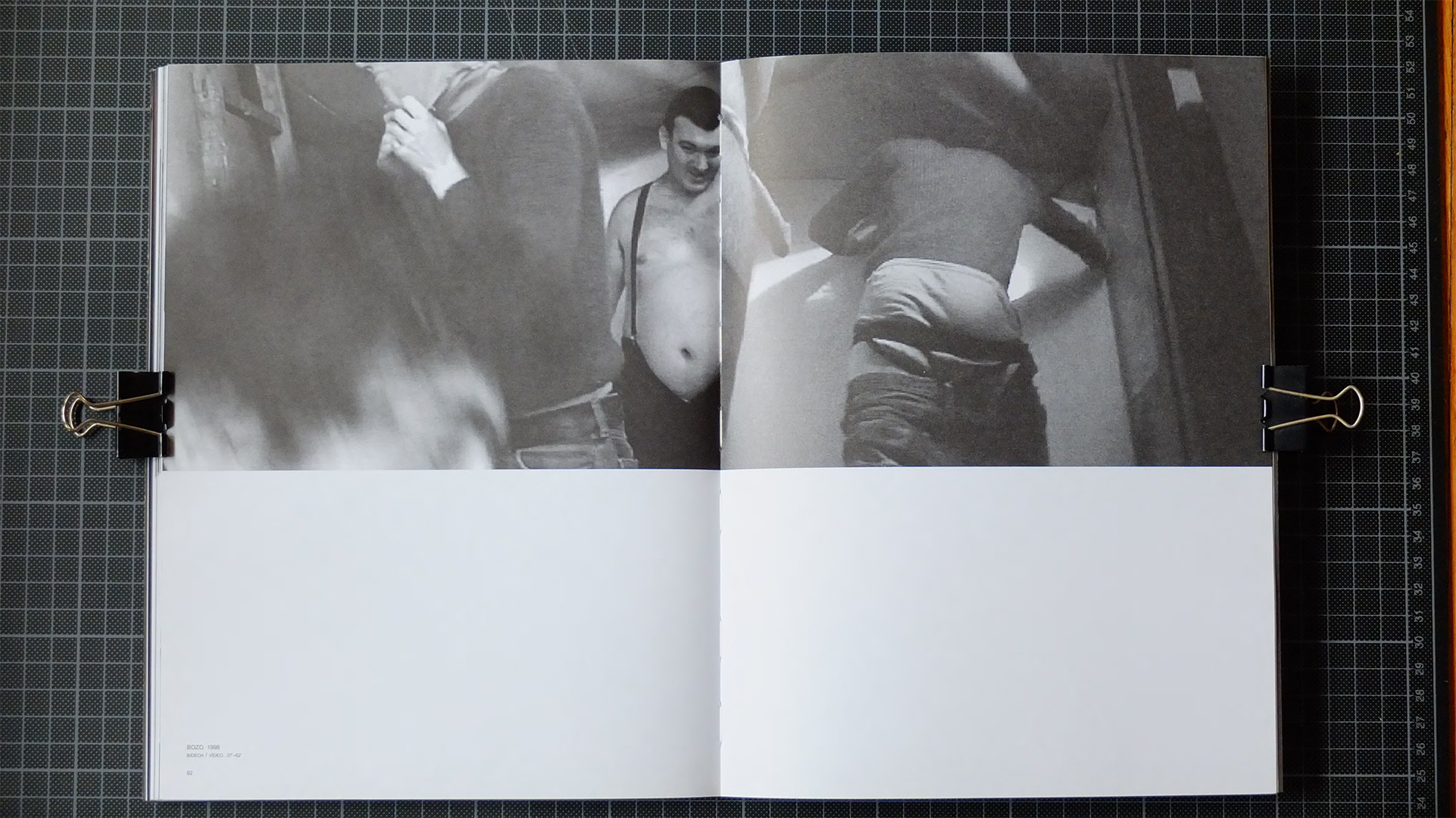

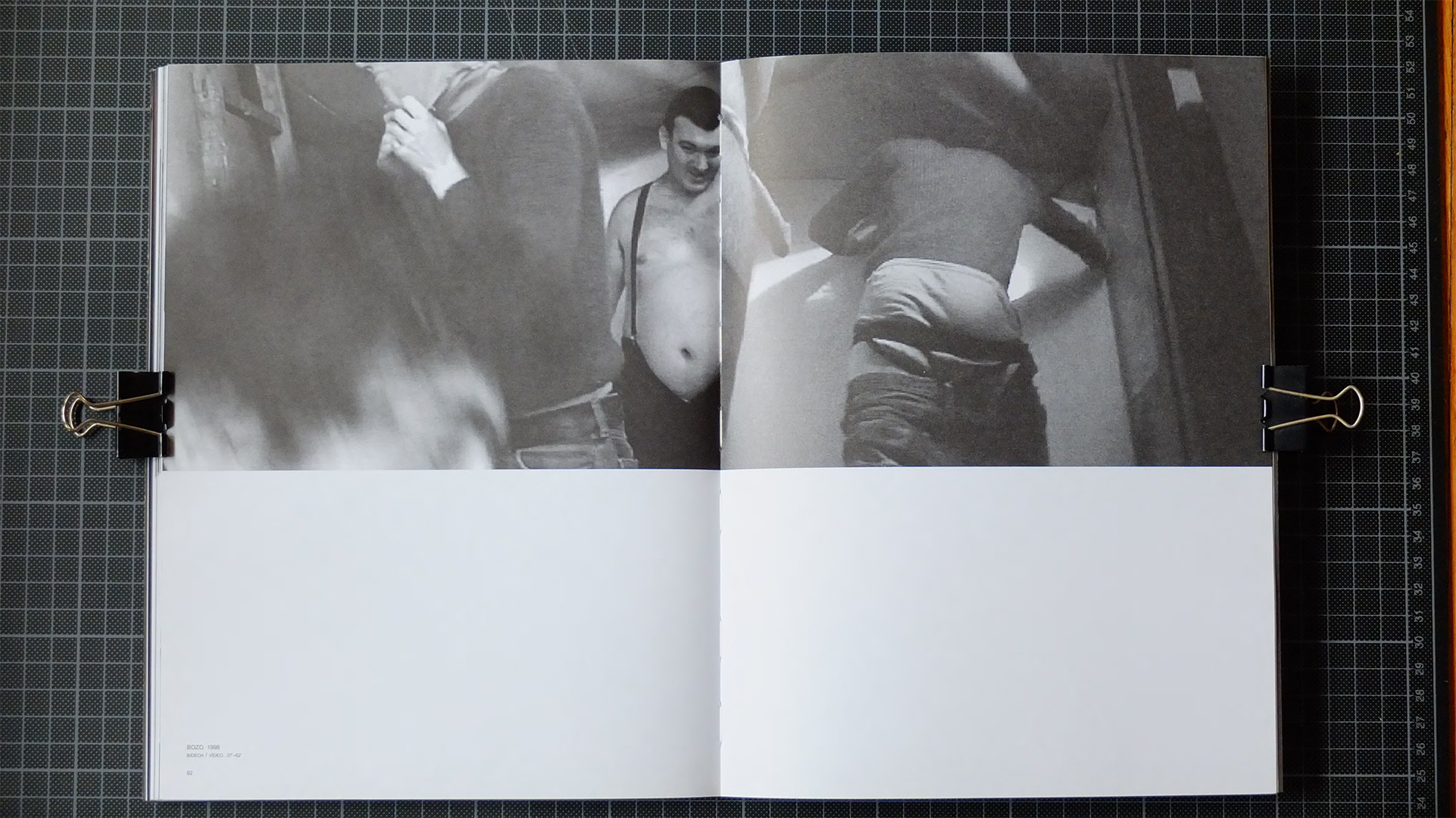

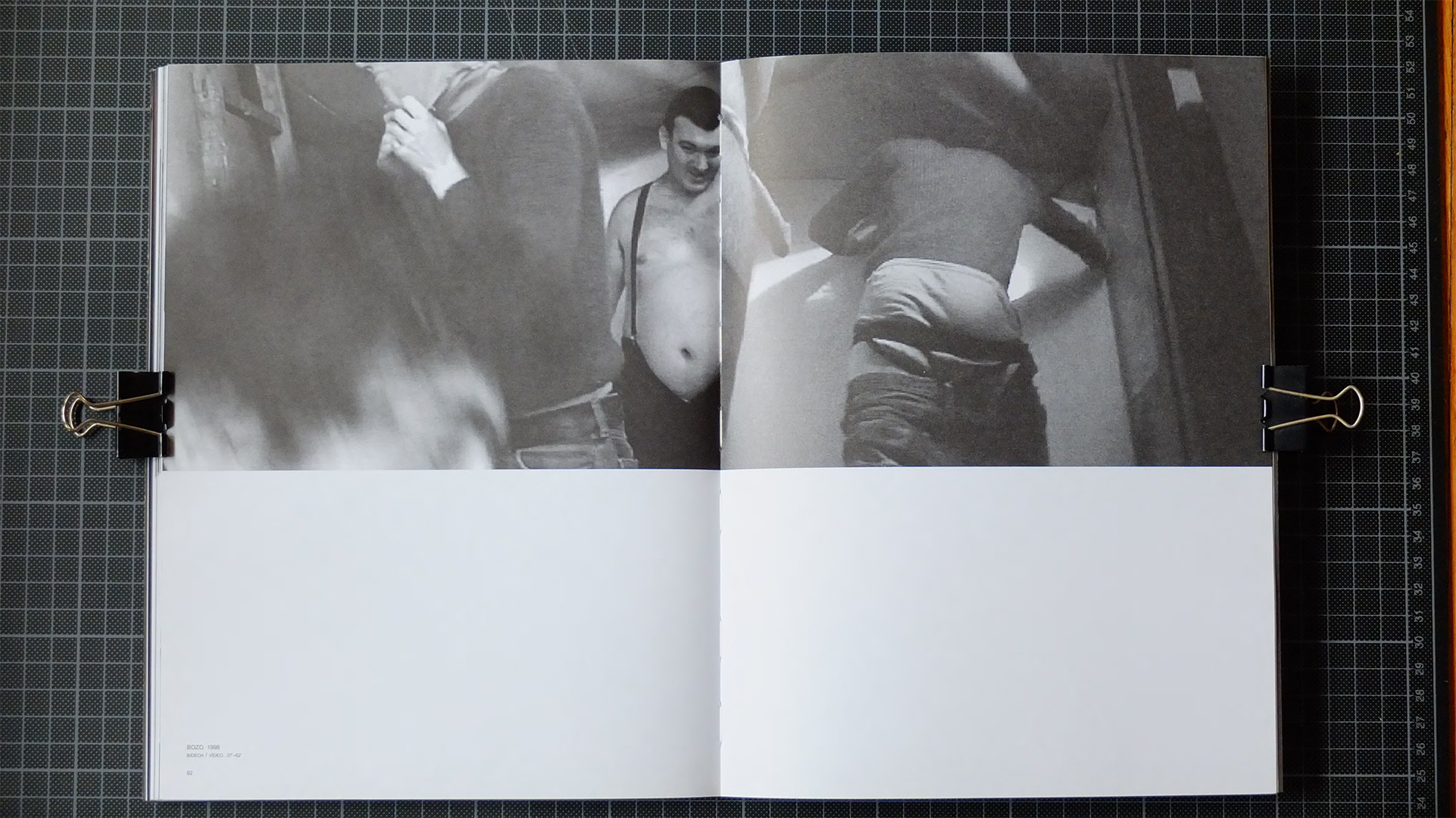

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

16’ 30’’

HD Video (1920 x 1080)

Recently, in relation to some moving images, I was thinking about the English term live images [imágenes en vivo], which could be translated into Spanish as “living images”. Do images have a life of their own? And if so, what is it that gives them life, the recording, the editing, the viewing? Do images have will?

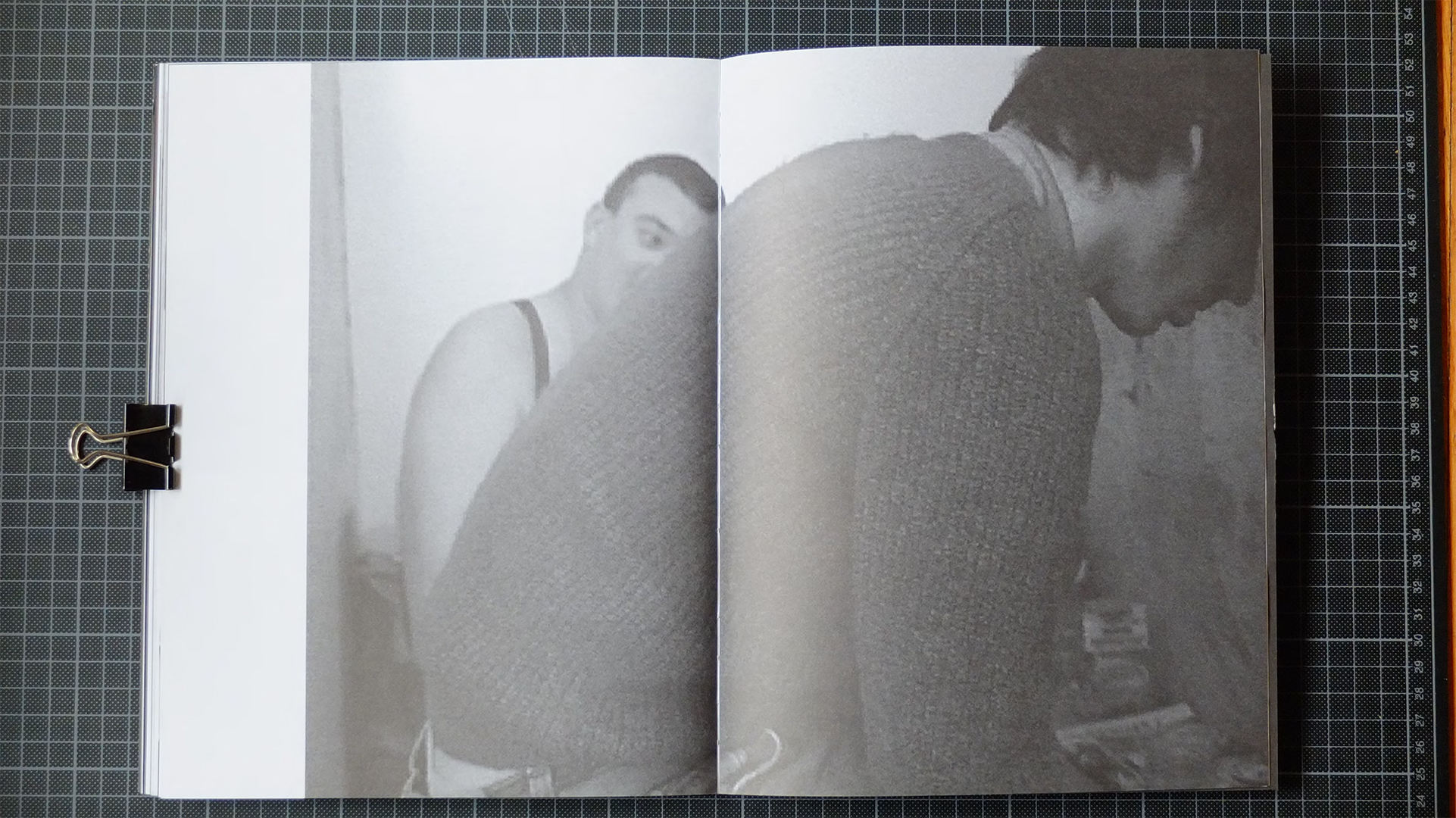

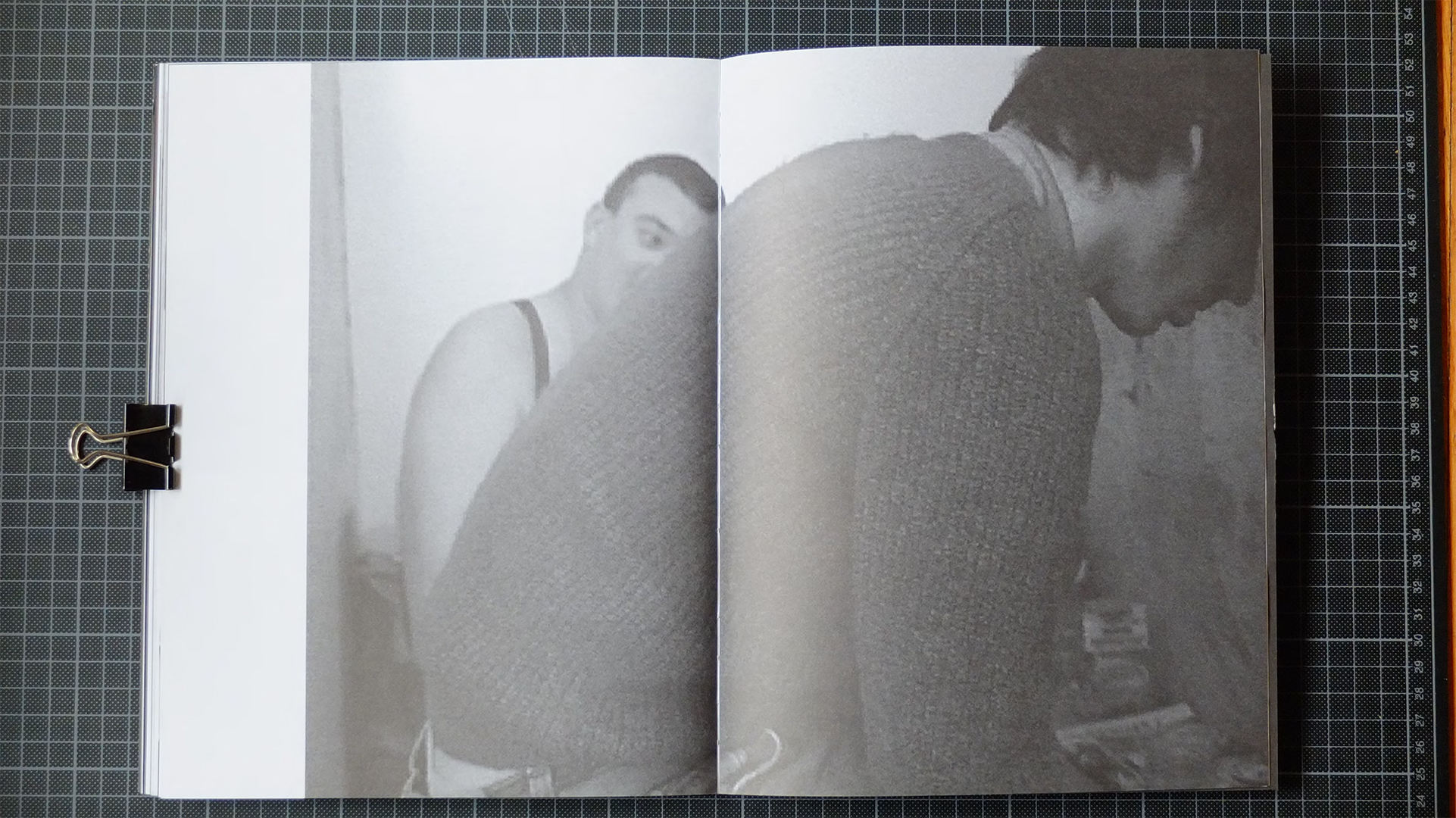

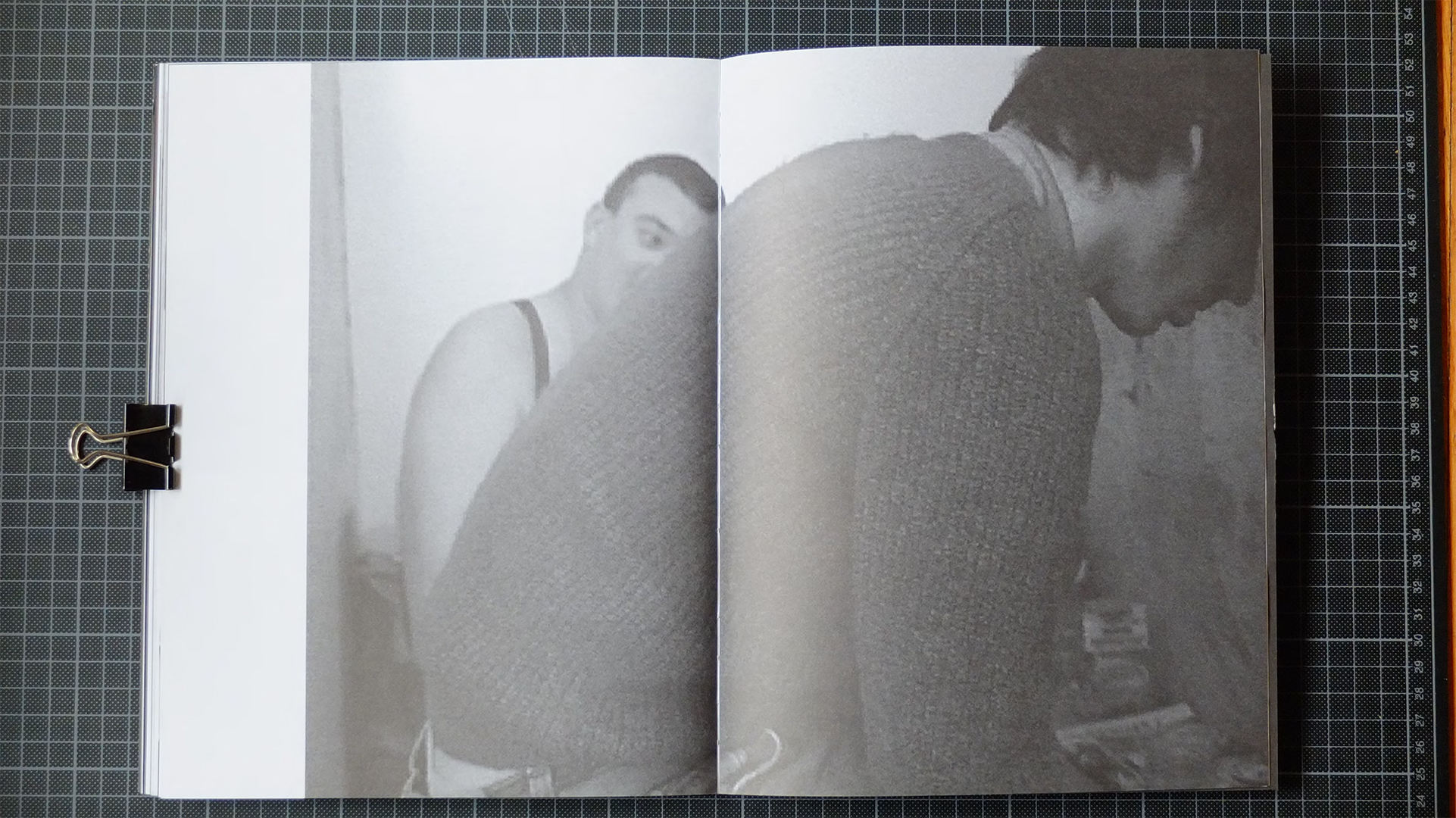

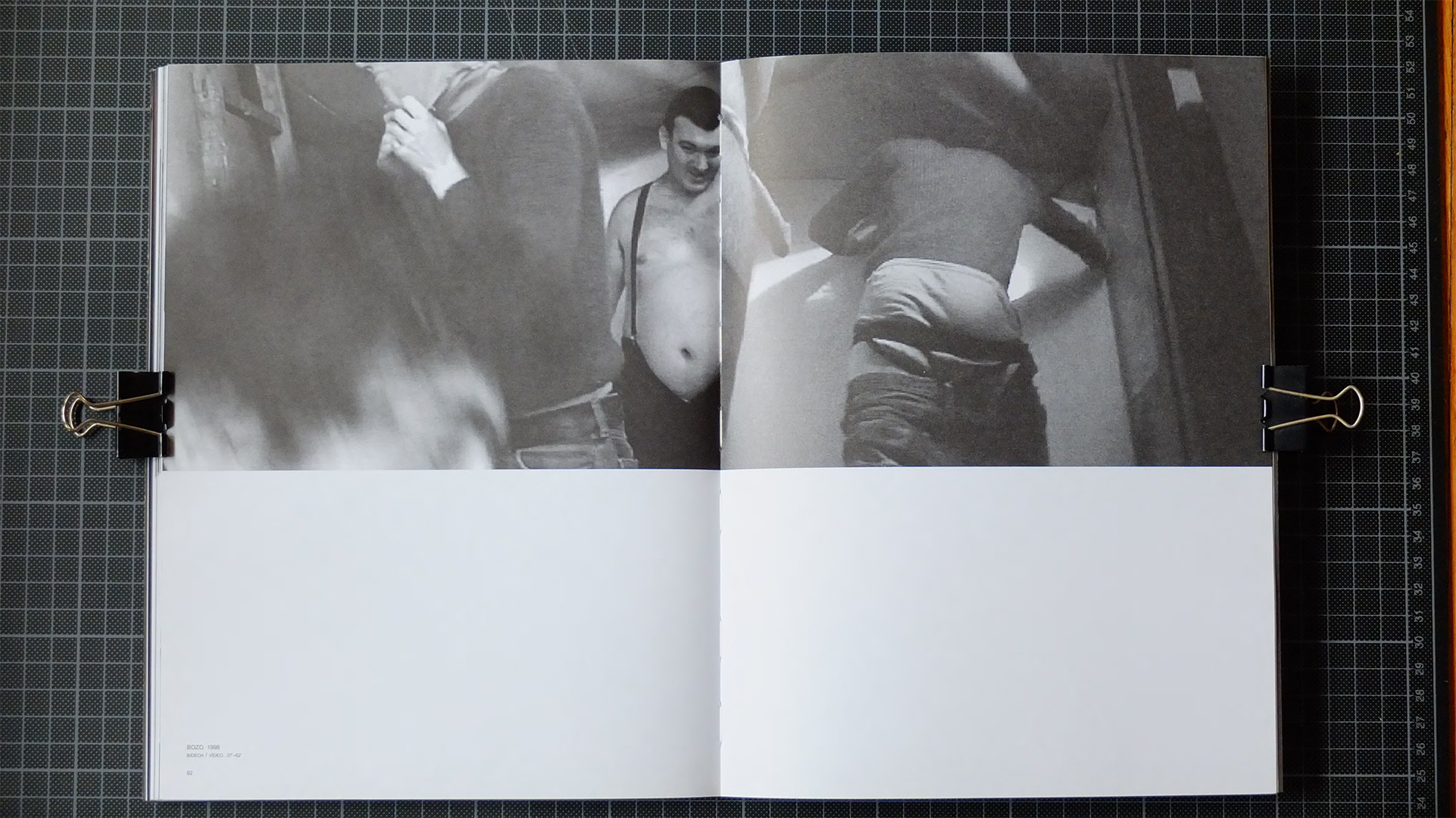

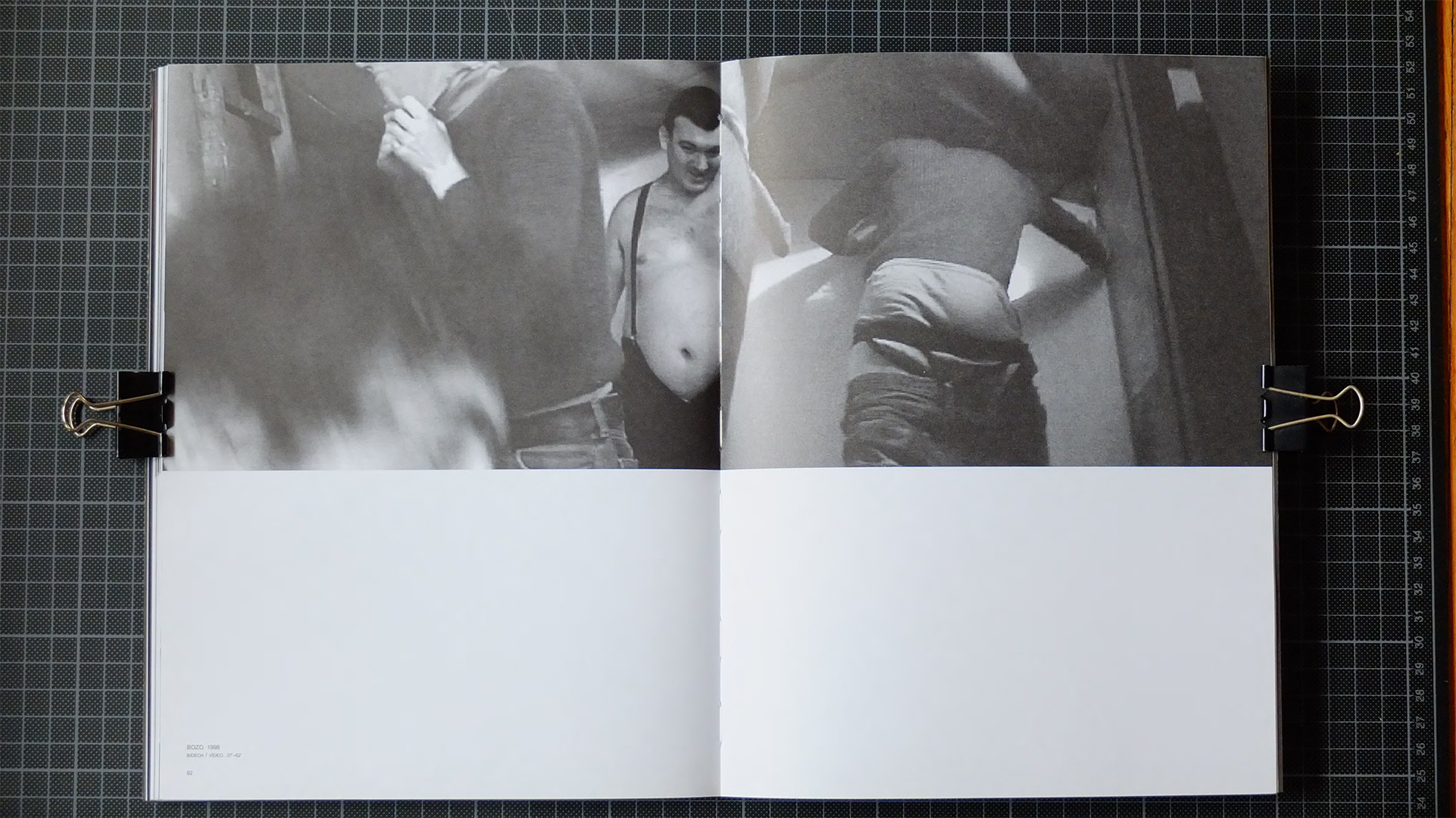

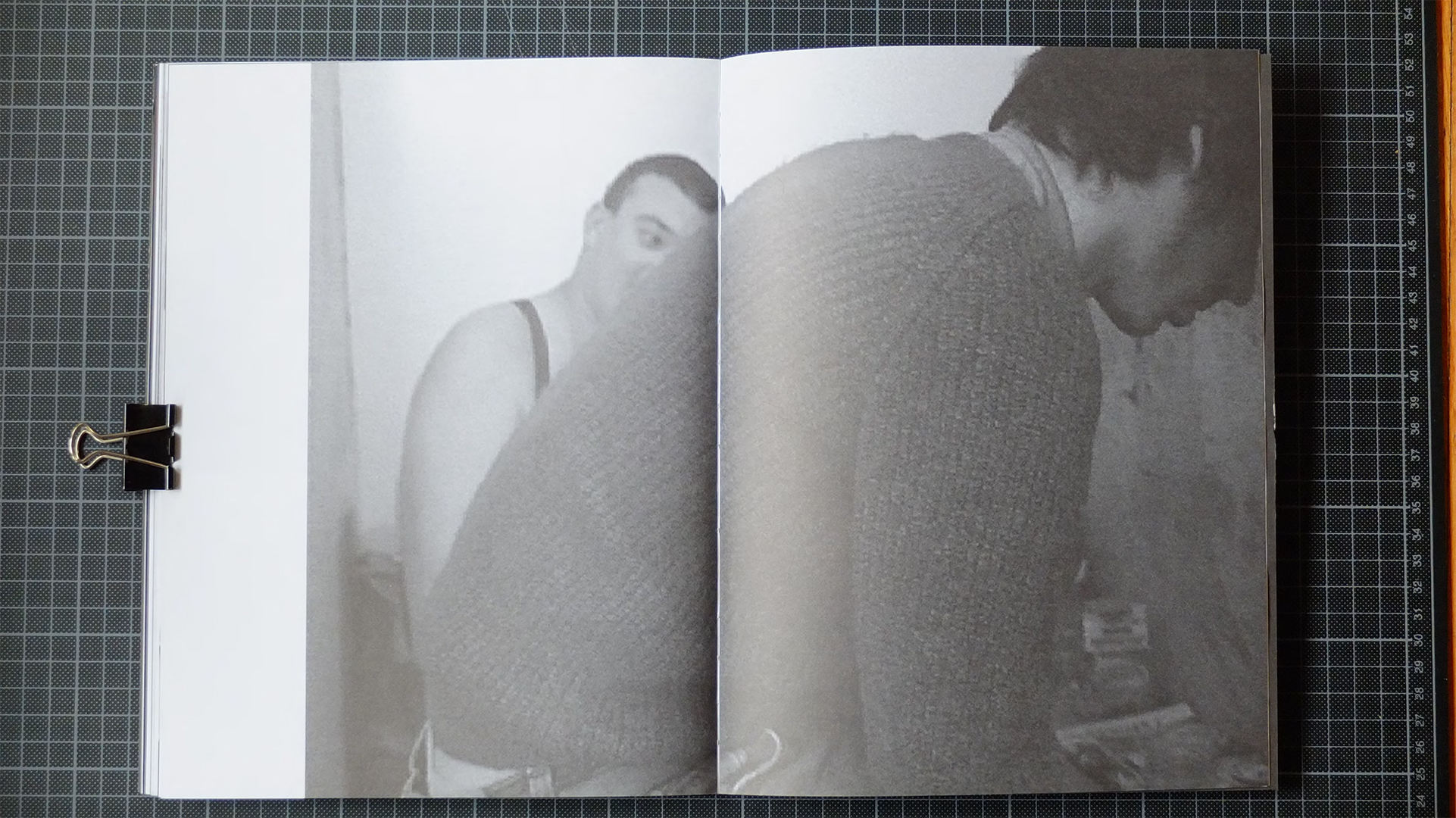

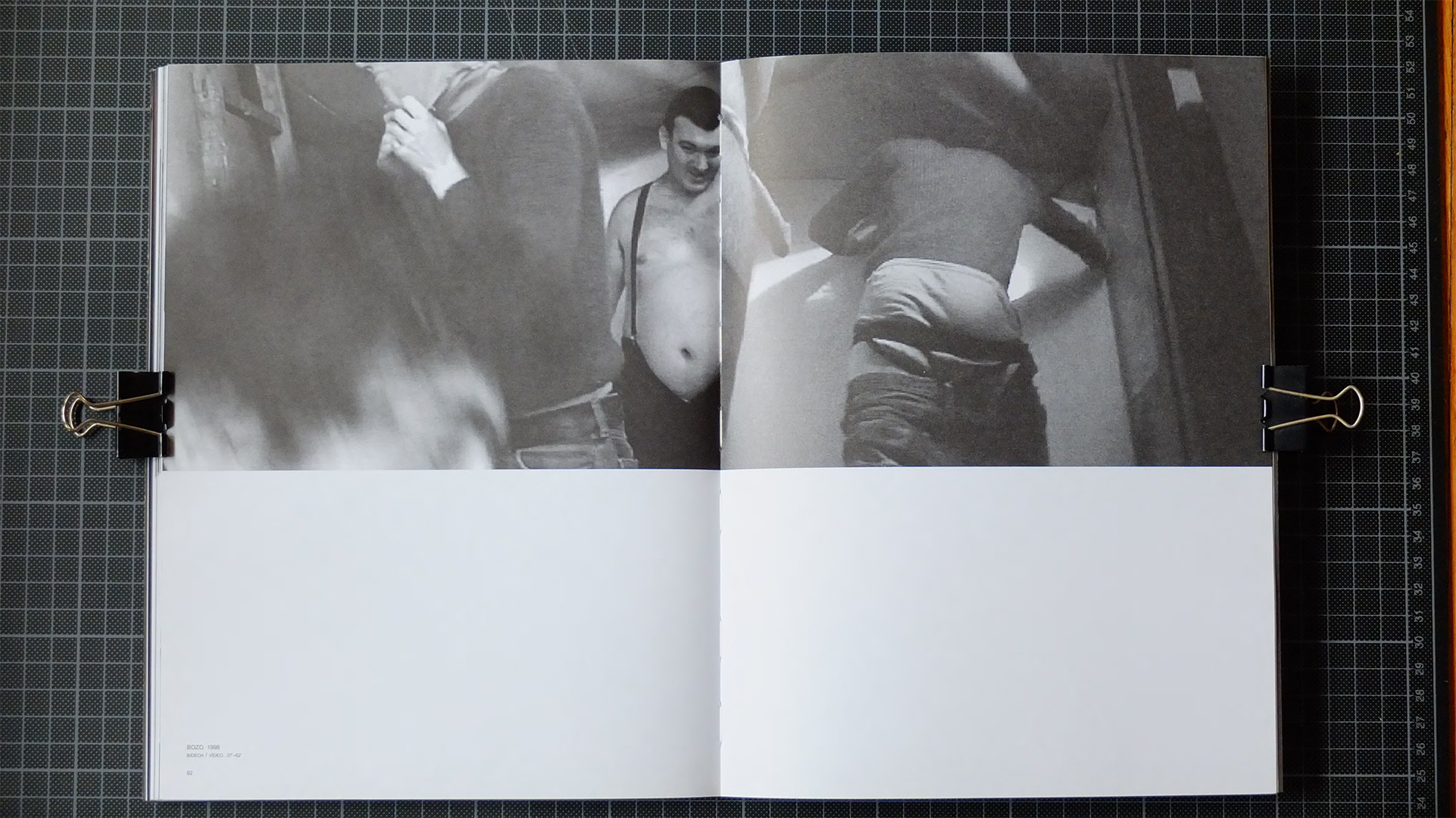

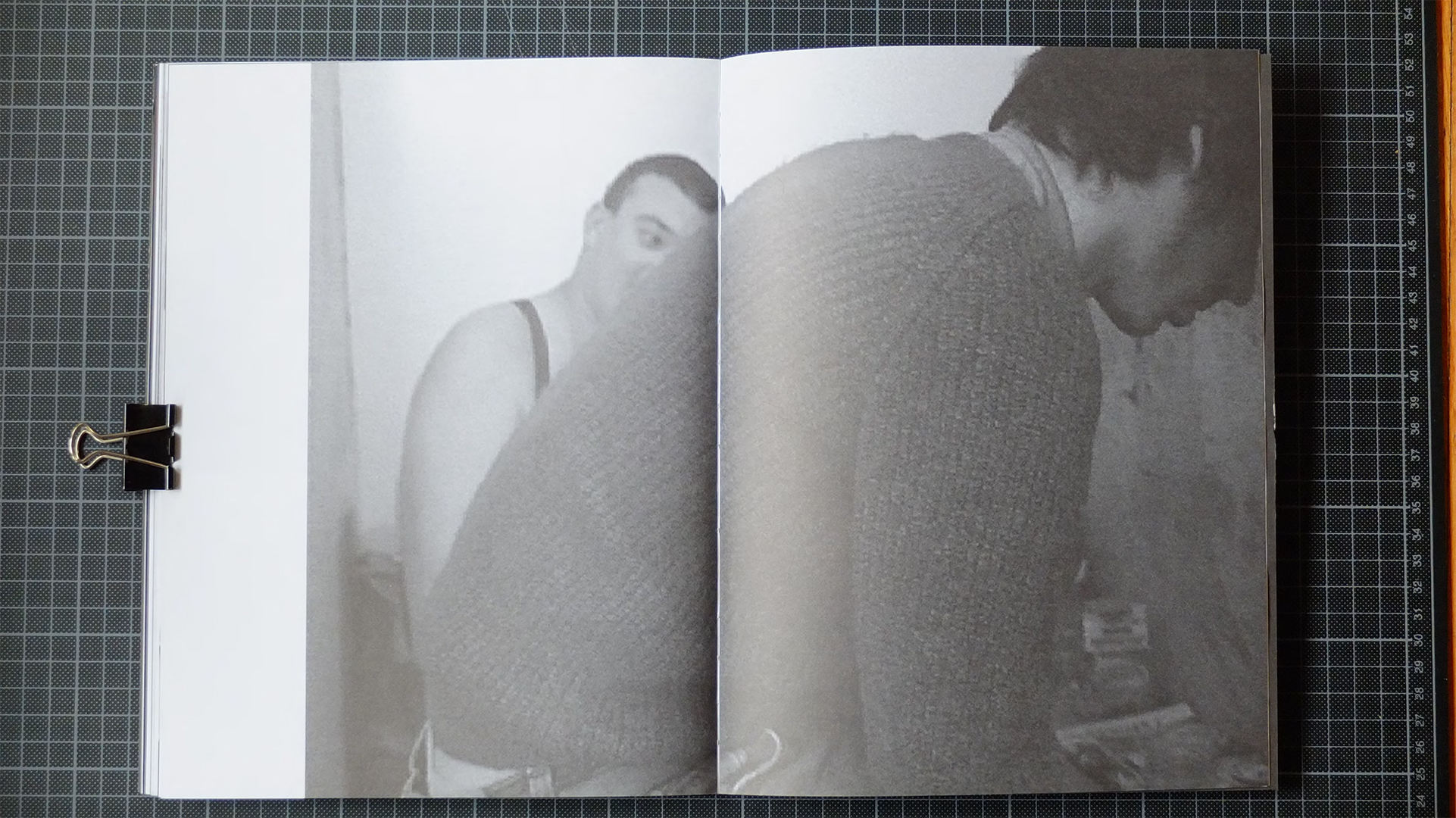

Bozo was recorded in 1997, but it was not exhibited until 2013, when it appeared for the first time as part of a solo exhibition in theMoisés Pérez de Albéniz Gallery, in Madrid. The delay between shooting and editing spans a little over fifteen years. The shooting was done in 1997, in the context of the Arteleku Workshop taught by Txomin Badiola and Ángel Bados. The recording took place in the studio space that the artist occupied during this period. The filming developed as a whimsical, childish game on a precariously constructed stage, a sort of dark room —or zulo— which could be accessed via an unstable ladder.

Bozo is a “black video” —this is the name Iñaki has given to the videos filmed with the same Tyco camera he used for No R.S. 99 Red Love Balloons—, but in this case bodies, not objects, are featured. A set of genitals has been transferred to a cast, which has then been reproduced in latex. The result appears strapped to a harness. We see a male body against the wall. It shows itself to be potentially penetrable, dismantling the position of representation of the cis man, according to Paul B. Preciado, as that of the natural and universal penetrator. The artist gives instructions to carry out the action, wearing a latex mask. The warm, mutual understanding between those present clashes with the crudeness of the images, making evident that the action is focused on constructing the scene.

In 2013, these brief sequences were put together on rectangular bands composing a triptych in the now standard 16:9 format. The editing is not linear, but arithmetic, and in it the strips are taken as the space for the horizontal representation of each of the bodies in scene (one of which is located behind the camera). The black and white clips move forward through the sections of the triptych while occasional accidents occur—a fade to blue, for instance, which takes us out of the foggy materiality of the Tyco image and brings out the traces of previous recordings on the VHS to which the original images were transferred. The final edit is the result of passing from one image format to another, of the visual encounter between two temporalities—1997 and 2013. Is the Rectum Straight?, Eve Kosofsky Sedwick wondered in 1993. Is the timeline between two dates straight, too? In Bozo, the time of the images is one which we are unable to access.

Related bibliography

Iñaki Garmendia. Police/Car. [Press release]. Madrid : Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, 2013.

Efectos de superficie. Iñaki Garmendia y Leire Vergara. [Unpublished interview]. [Bilbao : Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2013].

Unpublished dialogue between Leire Vergara and Iñaki Garmendia for Garmendia. Maneros Zabala. Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Bilbao (31/10/2013-16/02/2014). The artist answers questions on his work process, the importance of the script, interrelationships between different works, text/image correspondence, and tensions between subject and object.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

32’15’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

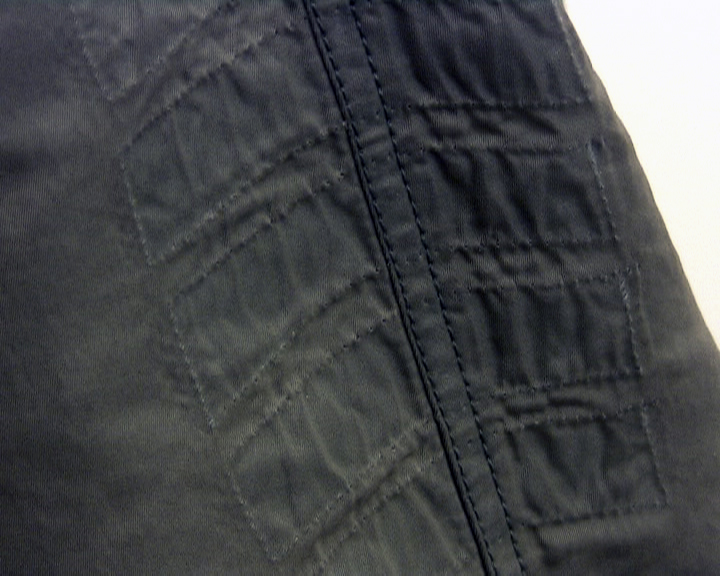

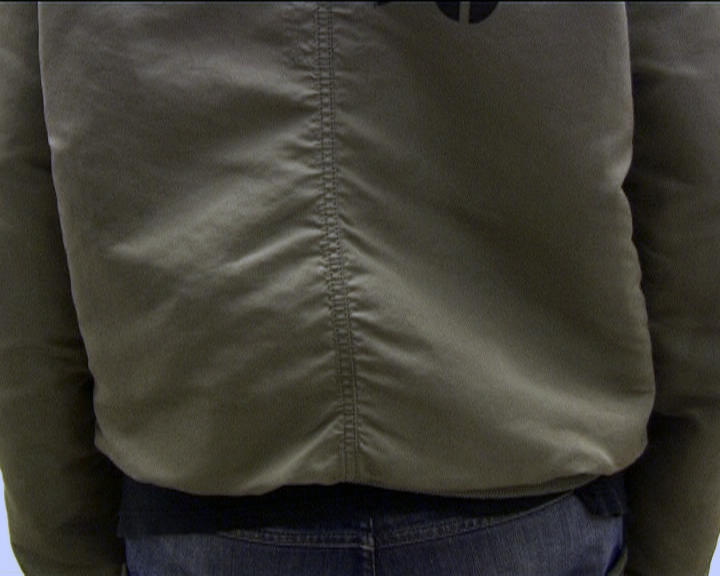

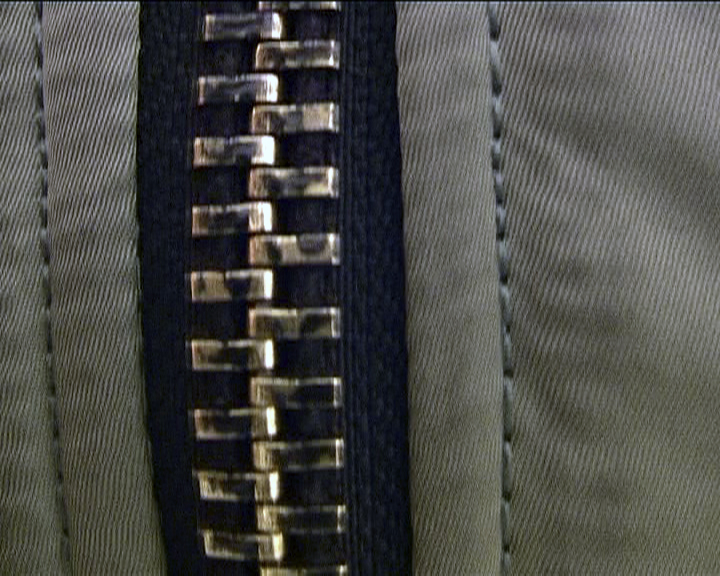

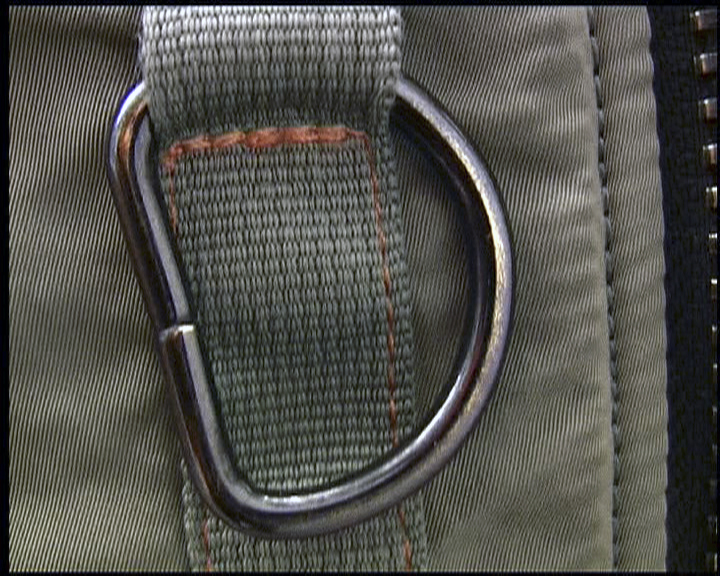

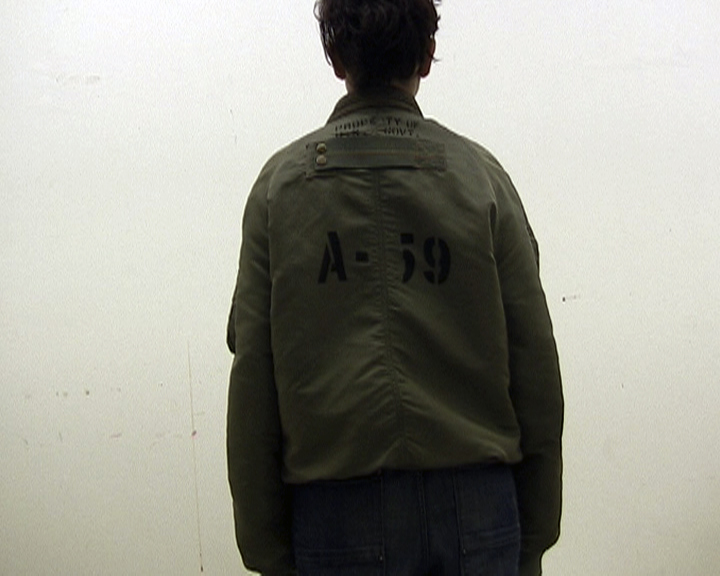

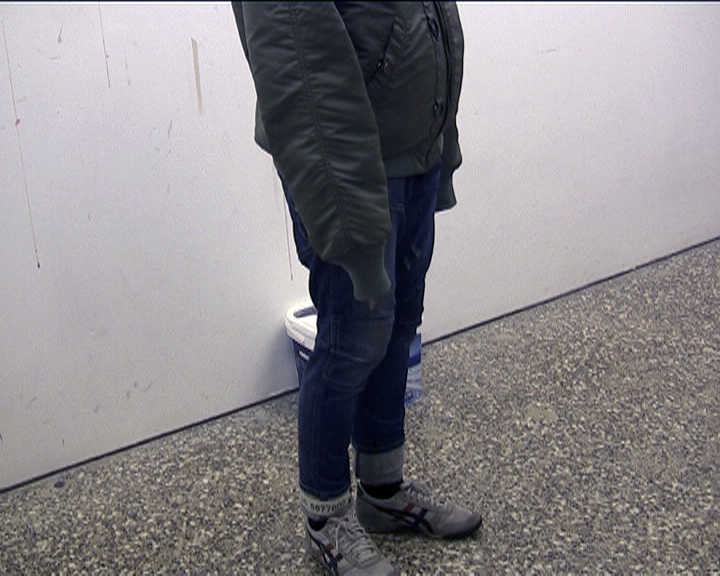

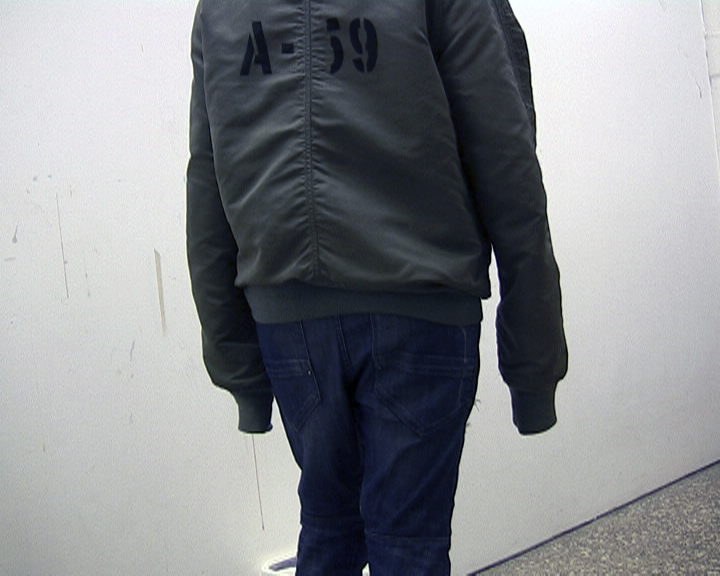

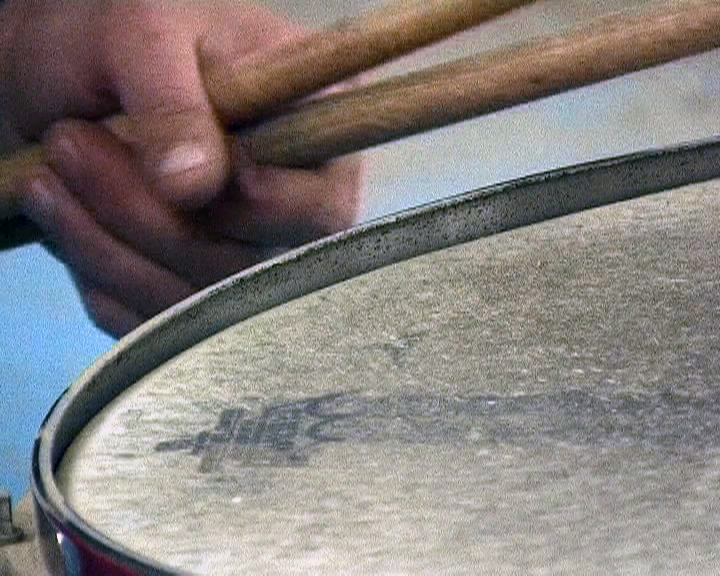

6 years after S/T Orbea (2007), Iñaki used the same technique to structure this 30-minute video. In Bomber, the camera runs its lens in long takes over the soft volume of a military bomber jacket. Once again, the macro lens touches the smooth surface of the object—in this case, a textile piece. The use of the close-up, in constant motion, produces a tactile vision as defined by Alois Riegl, materialising a haptic perception. A few minutes in, we recognise the jacket as belonging to Itziar, once we hear her answering to a series of instructions given to her by Iñaki. Itziar is wearing the jacket while it is being filmed. We discover it once the camera draws away for a bare, straightforward display of the garment on her body. The resulting image is more undefined than S/T Orbea, but equally iconic.

In the background, a young girl is speaking with someone in English. Her aural presence blends into a repetitive electronic melody, all of which leads us to understand the footage as a lived time. As we run our eyes over the jacket’s surface, the printed text on the clothing is gradually revealed; first, as a fragmented image; later, as writing printed on the textile surface. The bomber suggests different signifiers that may or may not be activated. In this piece, however, it is presented as a raw material capable of binding collective existences together.

Related bibliography

Iñaki Garmendia. Police/Car. [Press release]. Madrid : Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, 2013.

Efectos de superficie. Iñaki Garmendia y Leire Vergara. [Unpublished interview]. [Bilbao : Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2013].

Unpublished dialogue between Leire Vergara and Iñaki Garmendia for Garmendia. Maneros Zabala. Salaberria. Proceso y método, Guggenheim Bilbao (31/10/2013-16/02/2014). The artist answers questions on his work process, the importance of the script, interrelationships between different works, text/image correspondence, and tensions between subject and object.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

Pablo Marte. «Sector Conflictivo. #02: Iñaki Garmendia», Basilika. Podcast, 85 min. 31 sec.

Two-channel video, with sound, colour

45’59’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

A video of a couple. Two scenes reappear, assembled in a two-channel projection. A piece in which text is introduced, once again, as the symptom of a problem.

“What is a fake image?”, wonders Patricia, the young activist from Le Gai Savoir, in the empty television set where Godard’s film is being shot, as the May 68 protesters take to the streets. “That place where image and sound (seem) real,” she answers to herself. In Speaking about Godard, Kaya Silverman parts from this scene to speculate about the Barthesian degree zero of images and sounds. In the scene, the actors speak but do not listen to one another, which stifles the images in a fugue-like movement.

Riten’s proposal is to delve into the relationship between image and sound. To that end, it departs from the narrative standards of classical editing, seeking to distance itself from the forms of representation behind the assembly of sequences. Let’s apply it to Riten: 1 + 2. Miriam + Unai. Two actors read out a transcription of the dialogues in Bergman’s The Rite, filmed in 1969. The camera frames Miriam’s face, then Unai’s, and so on, which prevents us from seeing them looking at each other. We can only sense the scene in its entirety by the sound we hear off-screen, which we assume to be diegetic. There is no clear order and, at times, the dialogue seems fluid. At other times, it becomes abstract and numerical.

The images in the film are muted by the pressure of diction, the extras compensate for this absence by their efforts to defer the encounter between image and text.

The text being read aloud by Miriam and Unai is an SRT file with the film’s Spanish subtitles and time codes. The images of the film are silenced by the pressure of diction, the actors compensate for that absence by their effort to defer the encounter between image and text. The time of exposure in front of the camera expands like an endless wait. In this formless time, the actors themselves become images, the reflection of an action that attempts neither to be true nor false.

Two-channel video, with sound, colour

23’ 47’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

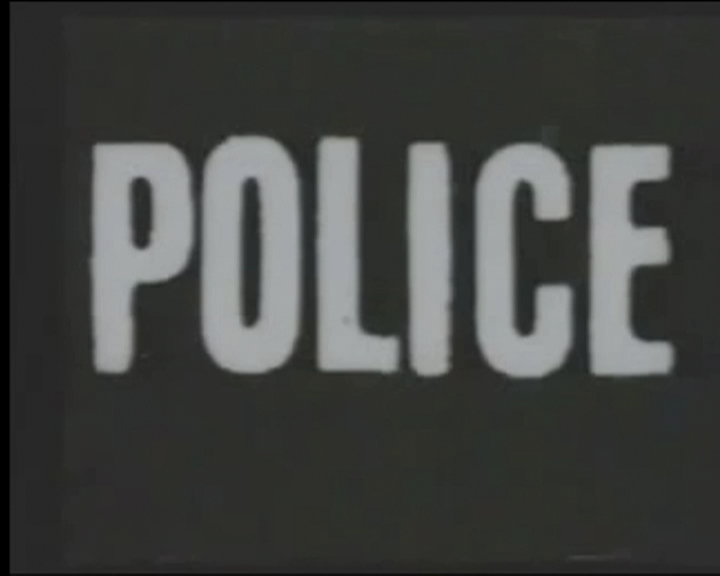

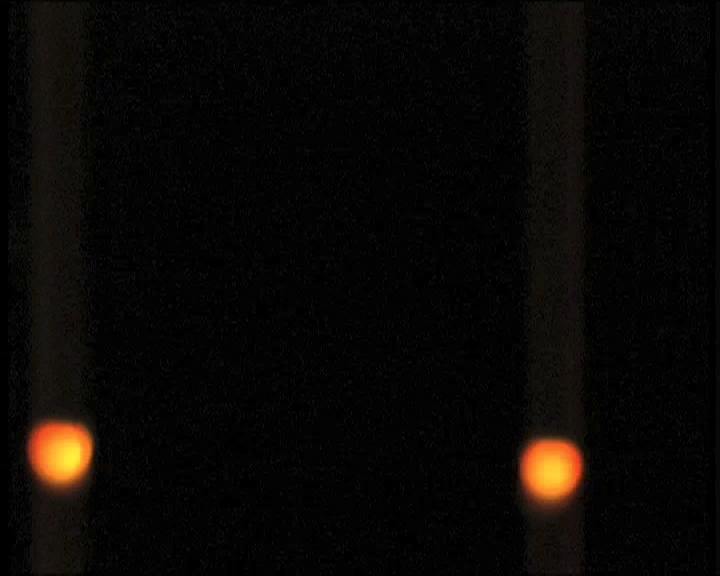

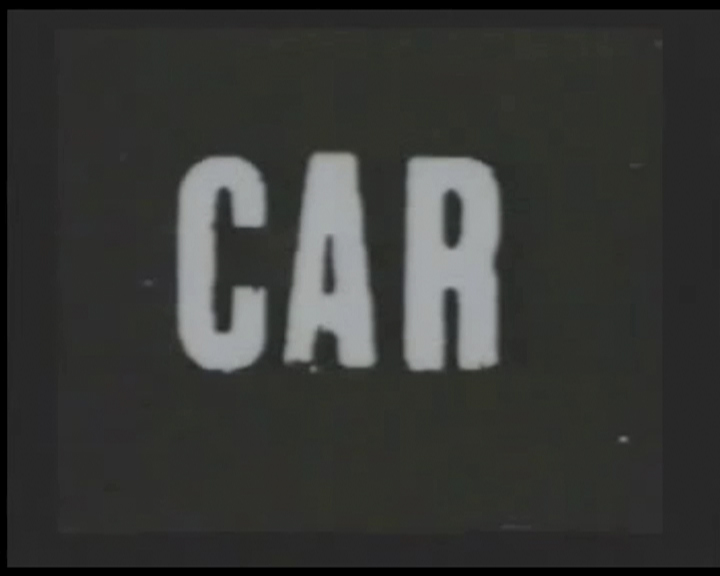

This work was first presented in 2013 as an installation at the Moisés Pérez de Albéniz Gallery in Madrid. A sculptural setting organises the space by assembling the sequences in a nonlinear way. One of these sequences displays the front view of a car’s position lights flashing in the dark. None of its distinctive features are perceived until the end of the recording, where its colour and number plate are revealed. The video, which plays in a loop, begins with a short clip in black and white that reads:

31

POLICE

CAR

The fragment is taken from John Cale’s minimalist film Police Car, included in the 1966 Fluxfilm Anthology. The sequences following this clip replicate Cale’s filming of a car’s indicator lights in the dark. Iñaki’s transcription should be understood as the reproduction of a choreography, in which the video camera goes over the different takes, replicating the positions of the 8 mm camera that were used in the film. The resulting image has nothing to do with Cale’s, –its visual effect is quite different—. The original was recorded on celluloid, in black and white, without a soundtrack, while the replica was recorded on video, in colour, and with background noise. The installation is completed by a second, longer sequence, in which the same white car (followed by a red one) is subjected to a thorough filmic examination similar to the one deployed in ST/Orbea and Bomber.

White Light/Red Light. Flashes that could perhaps be read as spectres of the intrahistory of subculture.

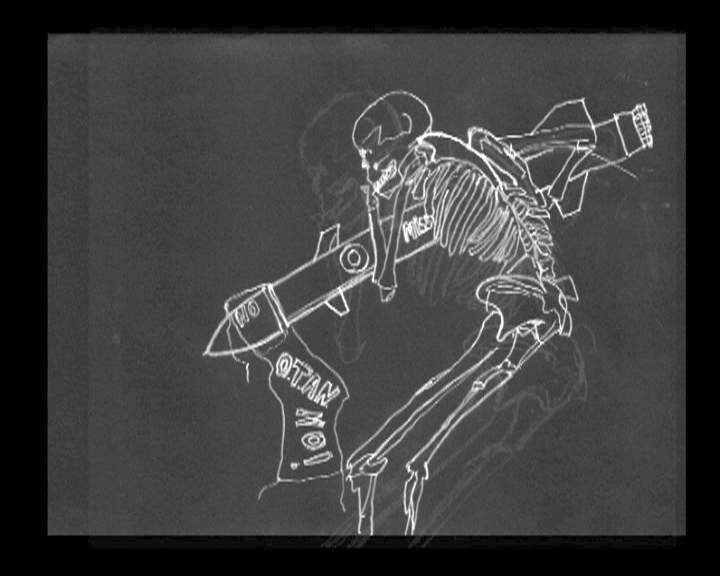

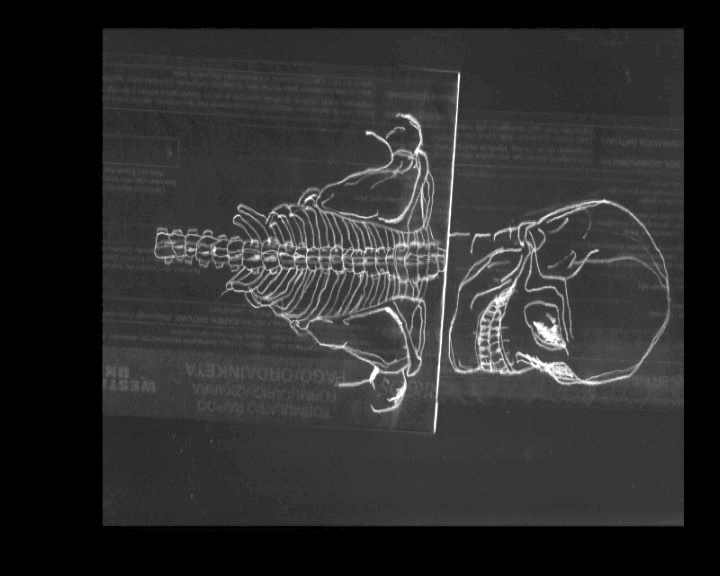

Single-channel video, silent, black & white

4’ 38’’

DV PAL (720 x 576)

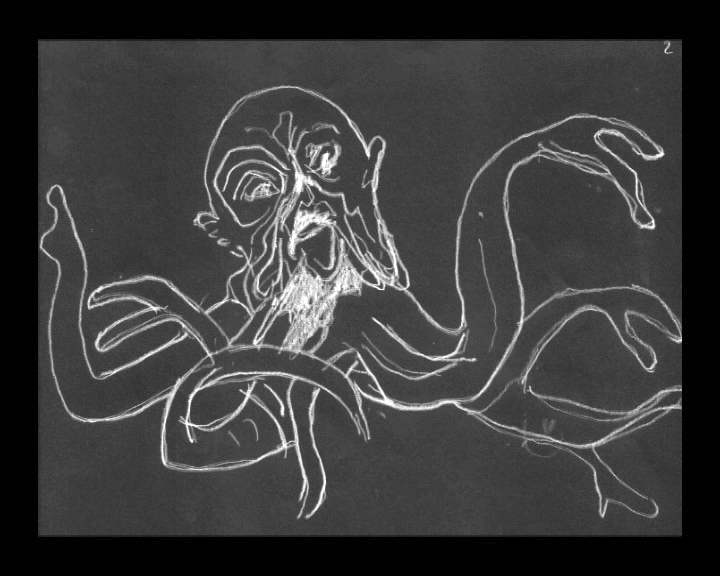

Garmendia’s first animated video. A collection of drawings takes cinematic shape during the editing process. The time that passes between each image is longer than what is stipulated by the conventional language of cinematic animation. His use of negatives, inverting the black on white of the original drawings, creates a disorienting, reverie-like effect. Together, it reveals the ecology of the assembly behind this piece.

Form becomes blurry: a surrealist still life, a site-specific exercise too, stemming from an invitation to exhibit at Okela artspace (Bilbao) and, as a response to the idea of history, a small homage to science fiction as a strategy to alter the logic in which the past is read. Several plotlines intertwine without a lineal chronological order. When the sequences meet they leave behind traces of latent individual and collective lived experiences, related to the moment in which the artist came to Bilbao to study Fine Arts. The film summons some images from the past, making them return, ghost-like. The most recognisable among them bring us back to the eviction of the Gaztetxe on Banco de España street, in Bilbao’s old town, in November 1992. New residues are created, such as a piece by Robert Smithson turned into a spaceship. The futuristic atmosphere invites the elements to indistinctly inhabit this intergalactic set: a skeleton, an AK-47 missile, the police chief, the emeritus king, a great octopus. Together they navigate through the footage.

The black surface contributes no more details on the context of these references, which might lead us to think about the problem of the survival of an image. The kinetic illusion that makes them appear and disappear equally disorients any attempt at representing the present, the past, and the future.

Single-channel video, with sound, colour

17'51''

HD Video (1920 x 1080)

DIVE OF THE HEAD OF «JS» IN THE ARKAKA DAM. We have left Bilbao in Ainara’s car, an hour and a half drive to go and the same back, we go to Zaldibia in Goierri; you can’t – there are restrictions, with perimeter closure etc. All with a pass – I have not seen it, mine: the paper – and a 4-hour work contract. Home by ten. Inside the car (we are picking them up on the way, Ainara drives while Usue checks if we have forgotten something). I knew “their” names when I wrote with a pen on the tape that I recorded: “ARKAKA-PRESA: ANDER Y MIREIA, 2-11-2020”. Just a month ago. In the trunk we carry: two cameras, three halogen flashlights (two of them front lights to guide us at night), 25 meters of 20mm transparent tube, a neoprene diver, an inflatable crocodile (with a pump) and JS’s head. (..) We left the car parked next to the central, so as not to be seen, that was the plan; it’s still daytime. Then Ander and Mireia carry the equipment to the edge of the dam that is hidden from the road. It’s six o’clock and we hear a car leaving the plant, two workers are leaving. Head stays in the car until dark (one hour left)

Iñaki Garmendia

Related bibliography

→ Ratatatatat, exposición inaugural de Atoi, nueva sede de Tractora Koop. Bilbao, dentro del programa FOKU, 26 Junio de 2021-15 de Octubre 2021.

Gorka Arrese. “Ingeltsuaren forma organikoak”, Berria, 10/08/2021, p. 10.

Review of Iñaki Garmendia´s “Ratatatat” solo show at Atoi by Gorka Arrese

Jone Alaitz Uriarte. “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, Argia, 2021/10/17.

Review of Iñaki Garmendia´s “Ratatatat” solo show at Atoi by Jone Alaitz Uriarte titled “Pogoak, rallyak eta ur sakonak”, which includes a number of video pieces which have been shown at foku.info.

Jone Gartzia Gerra. «Traktorearen atoia», Ortzadar – Deia, 30/10/2021, p. 02

Journal review in which Jone Gartzia writes about Atoi and the exhibition titled “Ratatatat” that Iñaki Garmendia is showing in that space.

Pablo Marte. «Sector Conflictivo. #02: Iñaki Garmendia», Basilika. Podcast, 85 min. 31 sec.

The second podcast of Basilika in the “Sector Conflictivo” series by Pablo Marte is dedicated to Ratatatat, the exhibition that Iñaki Garmendia has produced and showed in Atoi. “#02: Ratatatat, Iñaki Garmendia” is a mix two interviews, the first of which took place in Consonni, and the second in Atoi. The podcast contains an insightful and generous reflection on Iñaki’s work and methodology. The music that completes the interview is sourced from two audio tracks that Iñaki produced in Poland in 2007-2008, which compile a series of songs by Polish punk groups, a type of music that was called Fala, an equivalent to Radical Basque Rock.