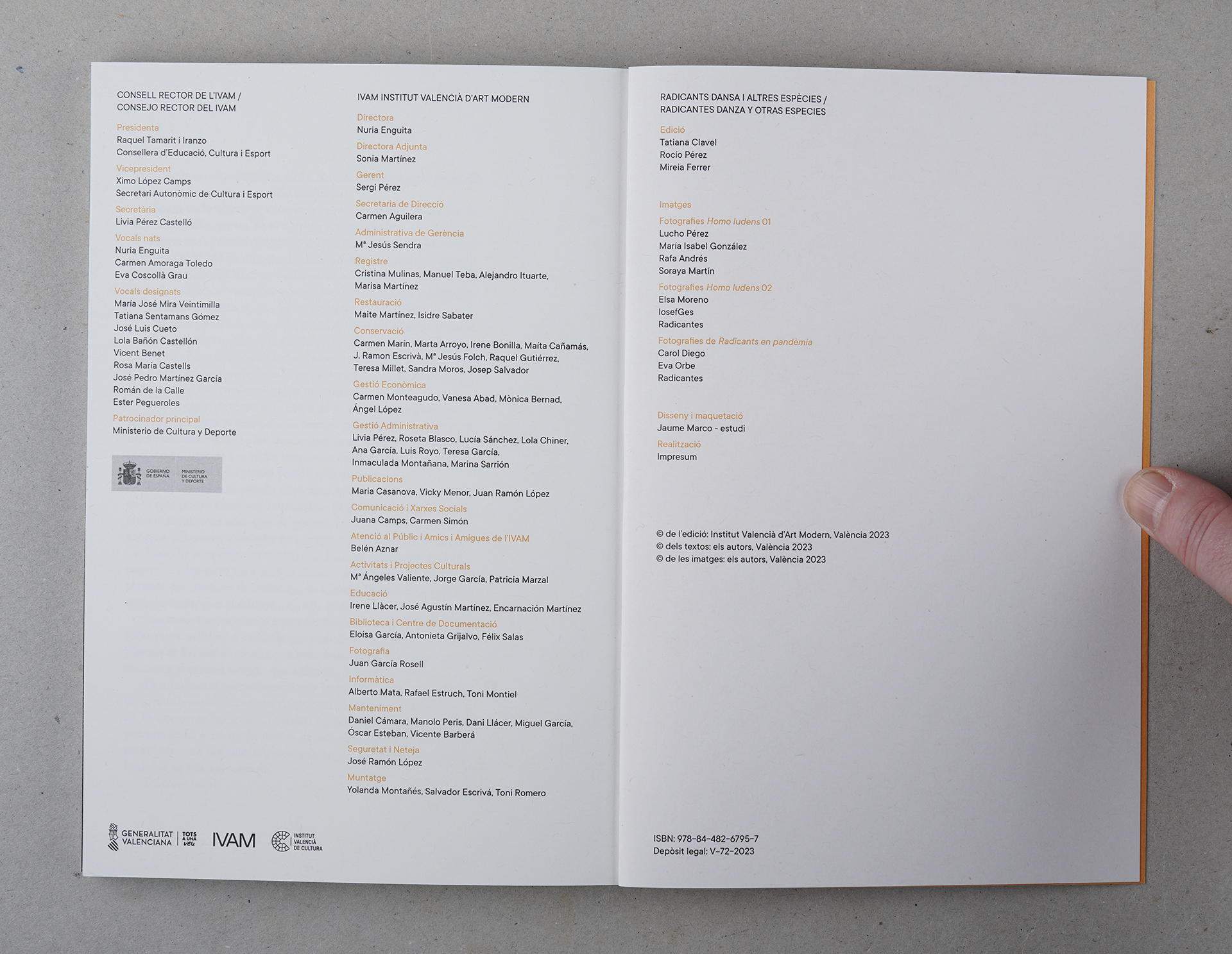

→ El rato de José at STUK (House for Dance, Image and Sound), Leuven, Belgium.

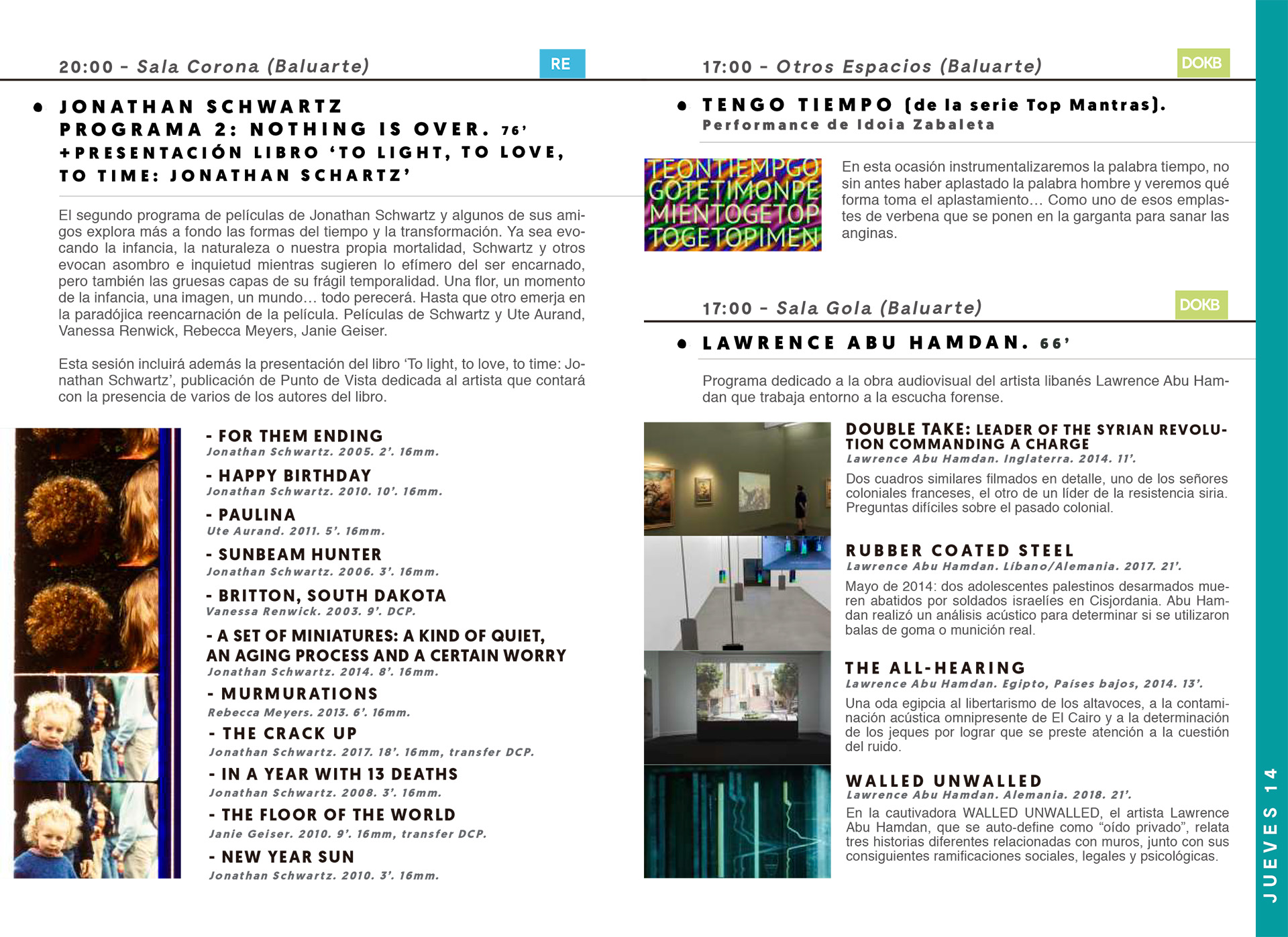

Mantra Noístas (2016)

Audio recording, stereo. 3′ 00″

Mantra Porvenir (2019)

Digital video, with sound, in colour. 5′ 33″

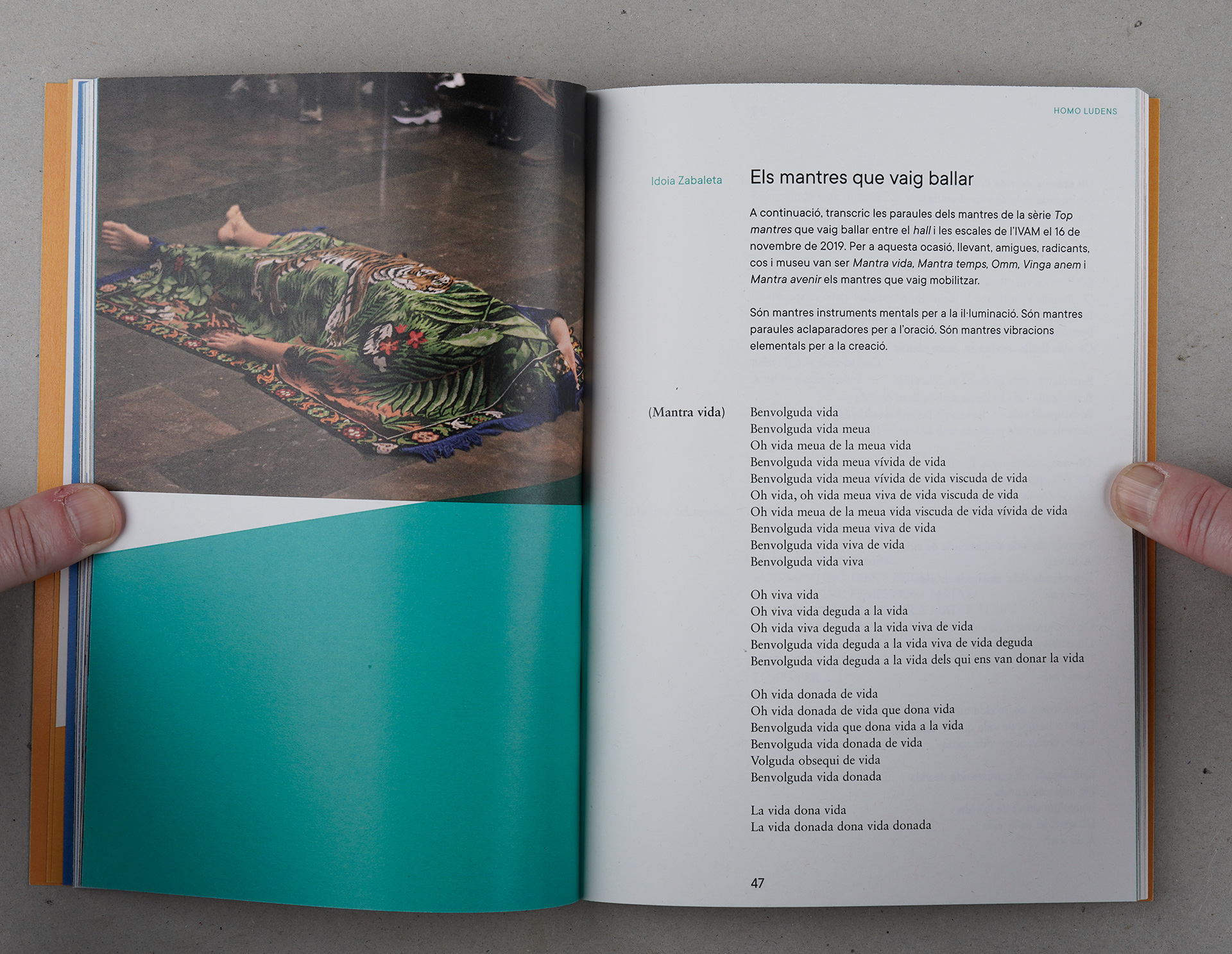

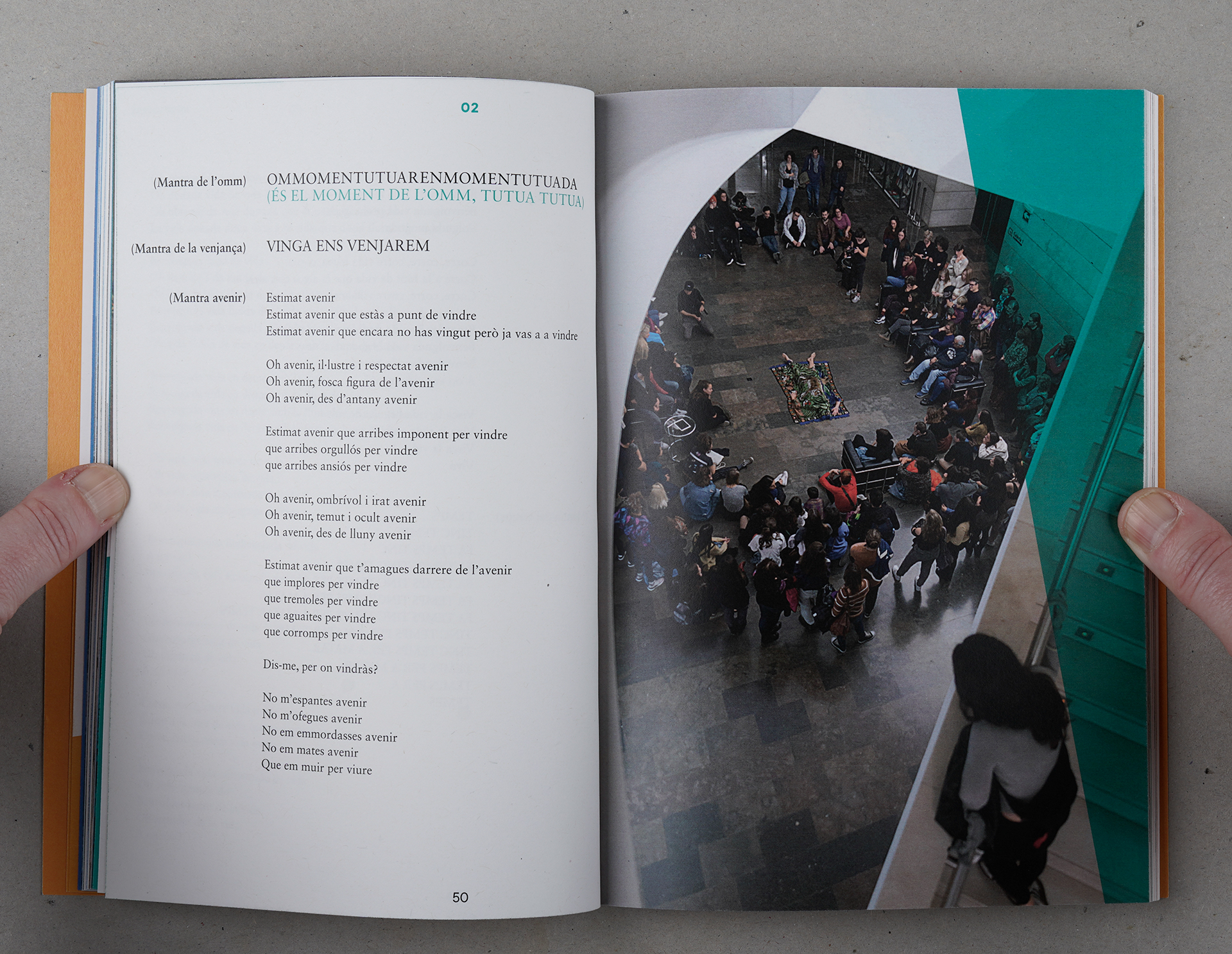

Video recording of the performance, as part of Top Mantra

Ideorritmias programme, 2021

© MACBA

Barcelona

Mantra Todas queremos pan (2019)

Audio recording, stereo. 1′ 47″

Mantra Mientras tú (2019)

Audio recording, stereo. 3′ 01″

Mantra Masculino (2019)

Audio recording, stereo. 44″

Mantra Dame la mano urgente (2019)

Audio recording, stereo. 2′ 22″

Mantra Luz (2020)

Audio recording, stereo. 58″

Mantra Deberías pedirle perdón (2020)

Audio recording, stereo. 2′ 24″

Mantra Ay la vida bonita (2020)

Audio recording, stereo. 32″

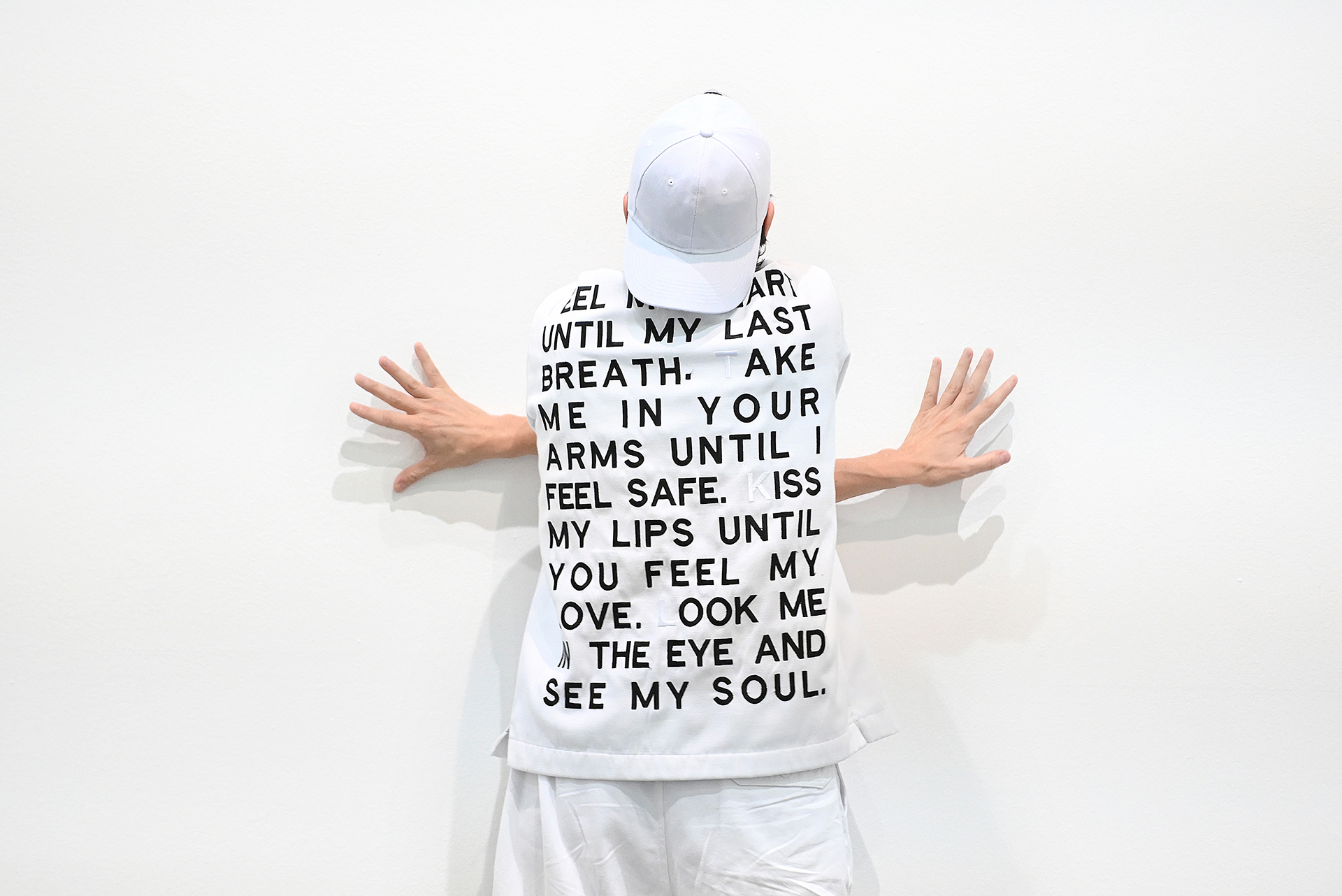

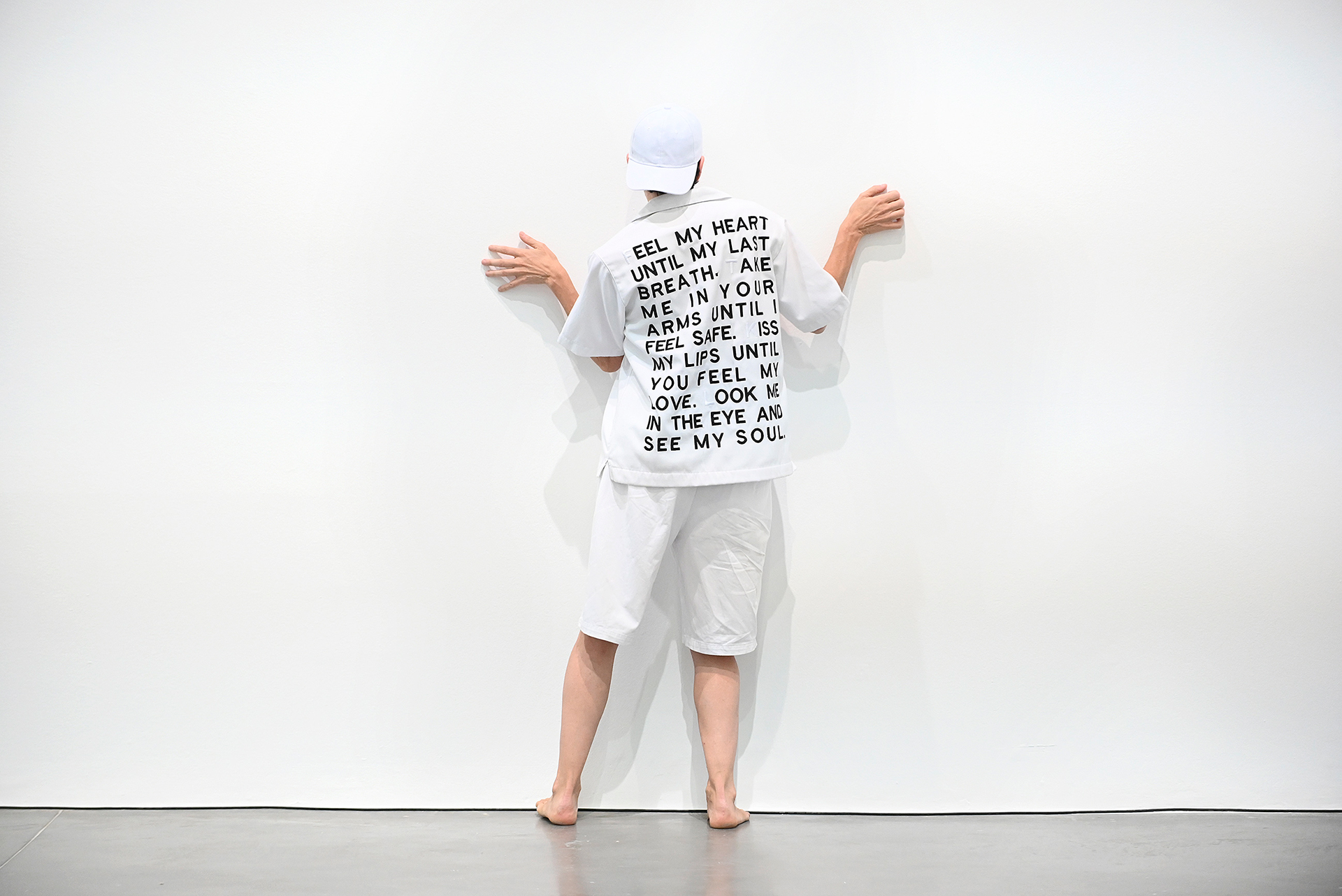

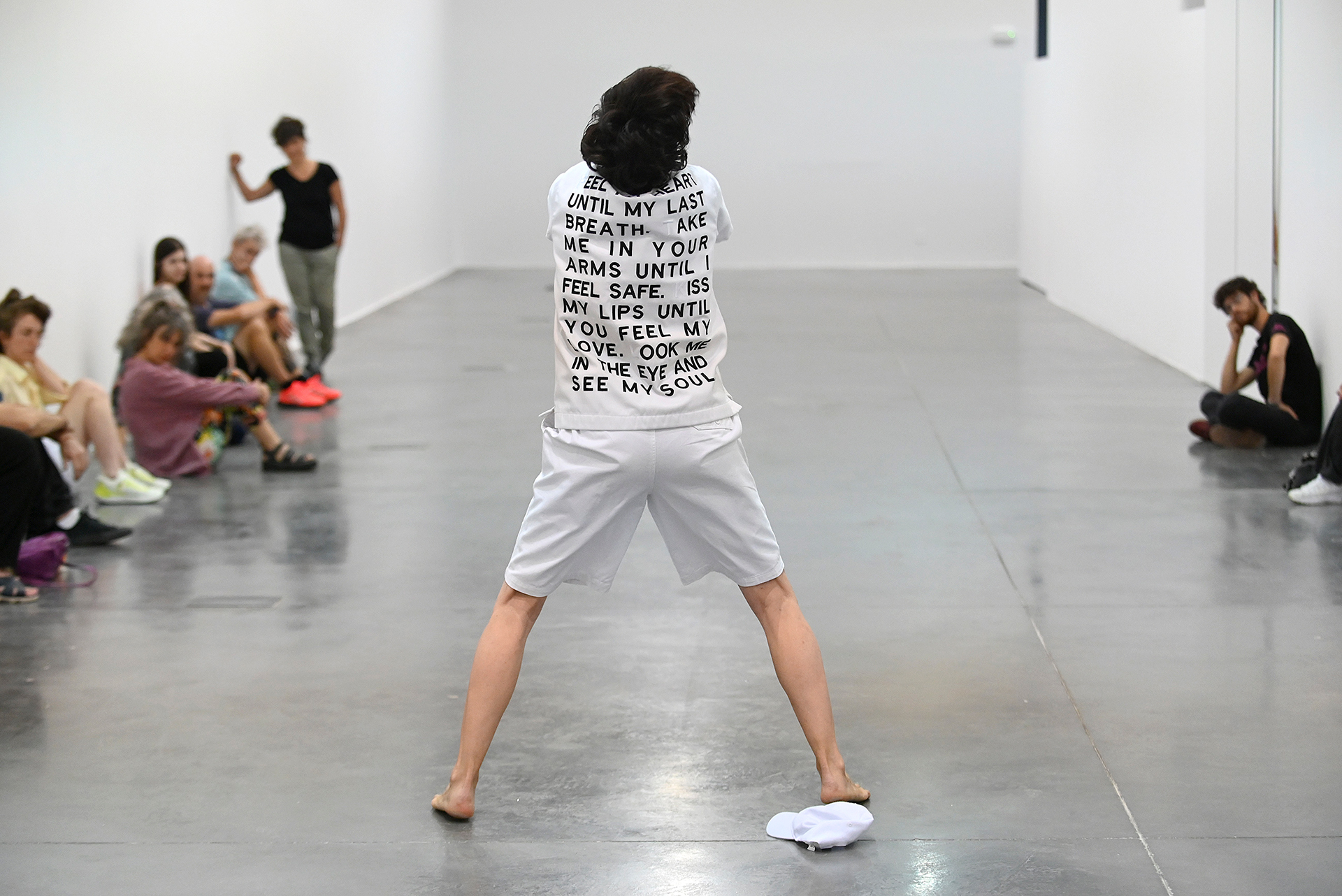

Mantra Pared (2021)

Digital video, with sound, in colour. 5′ 36″

Video recording of the performance, as part of Top Mantra

Ideorritmias programme, 2021

© MACBA

Barcelona

Mantra Déjala Ser (2021)

Digital video, with sound, in colour. 4′ 45″

Video recording of the performance, as part of Top Mantra

Ideorritmias programme, 2021

© MACBA

Barcelona

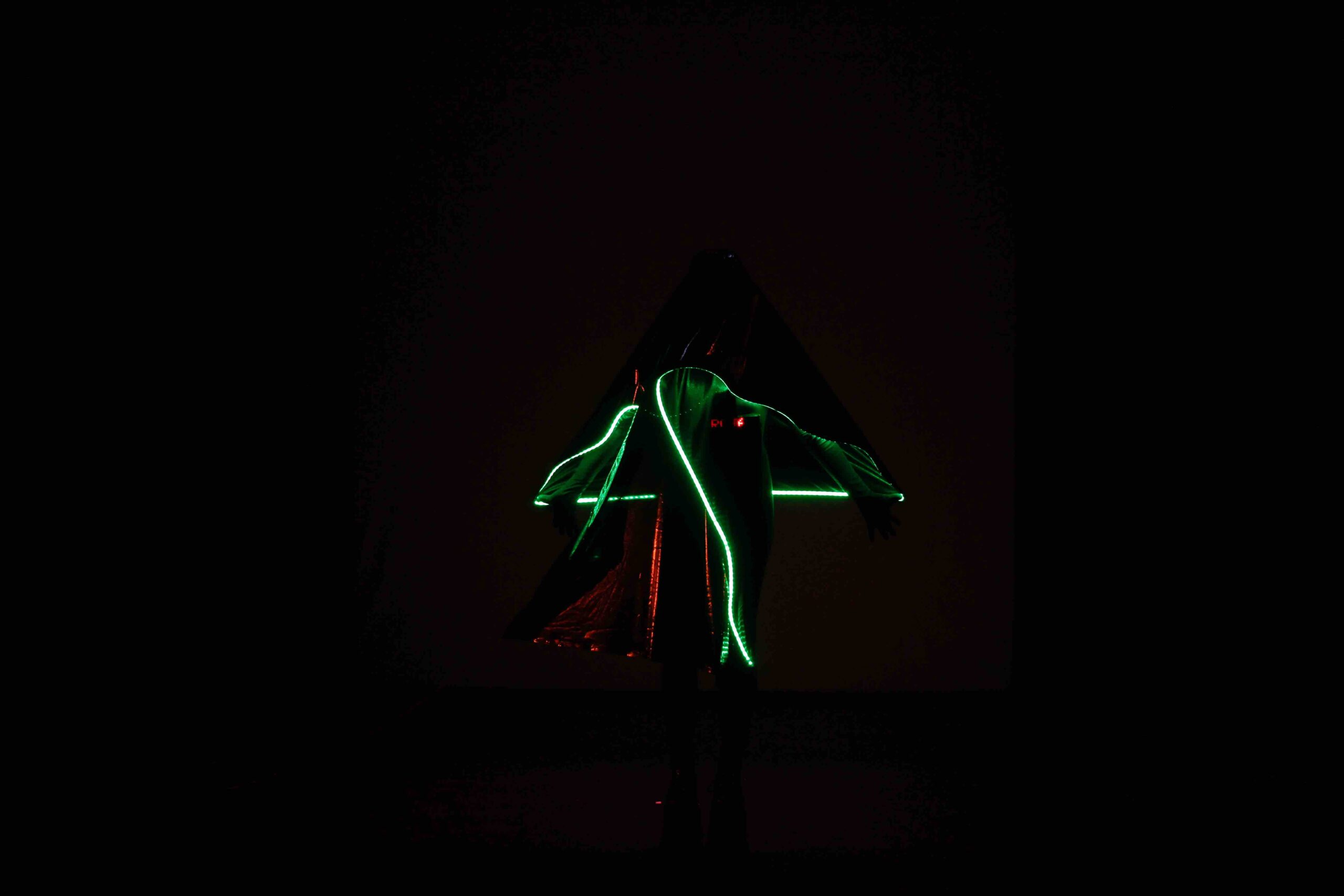

Mantra Chamán (2021)

Digital video, with sound, in colour. 7′ 28″

Video recording of the performance, as part of Top Mantra

Ideorritmias programme, 2021

© MACBA

Barcelona

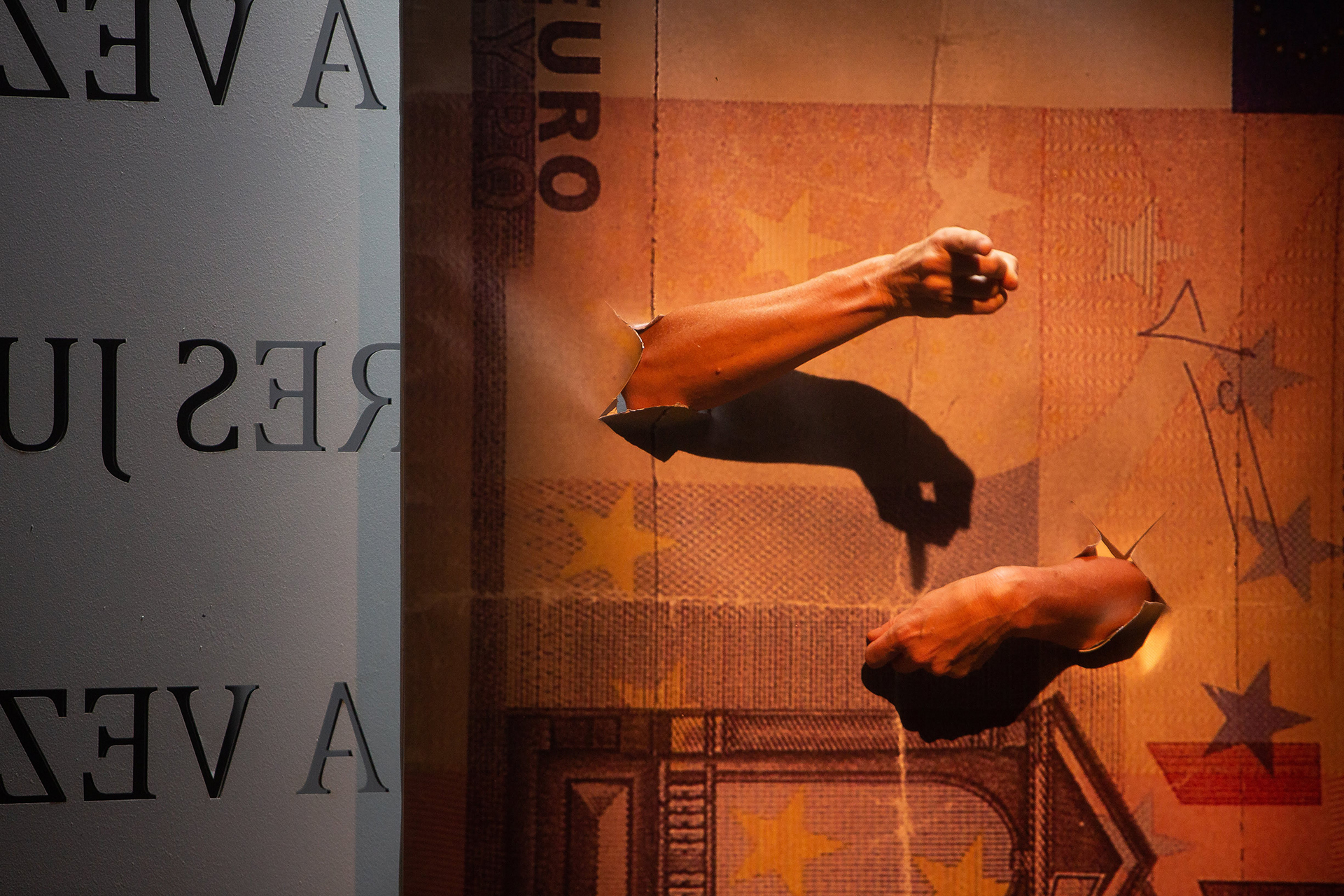

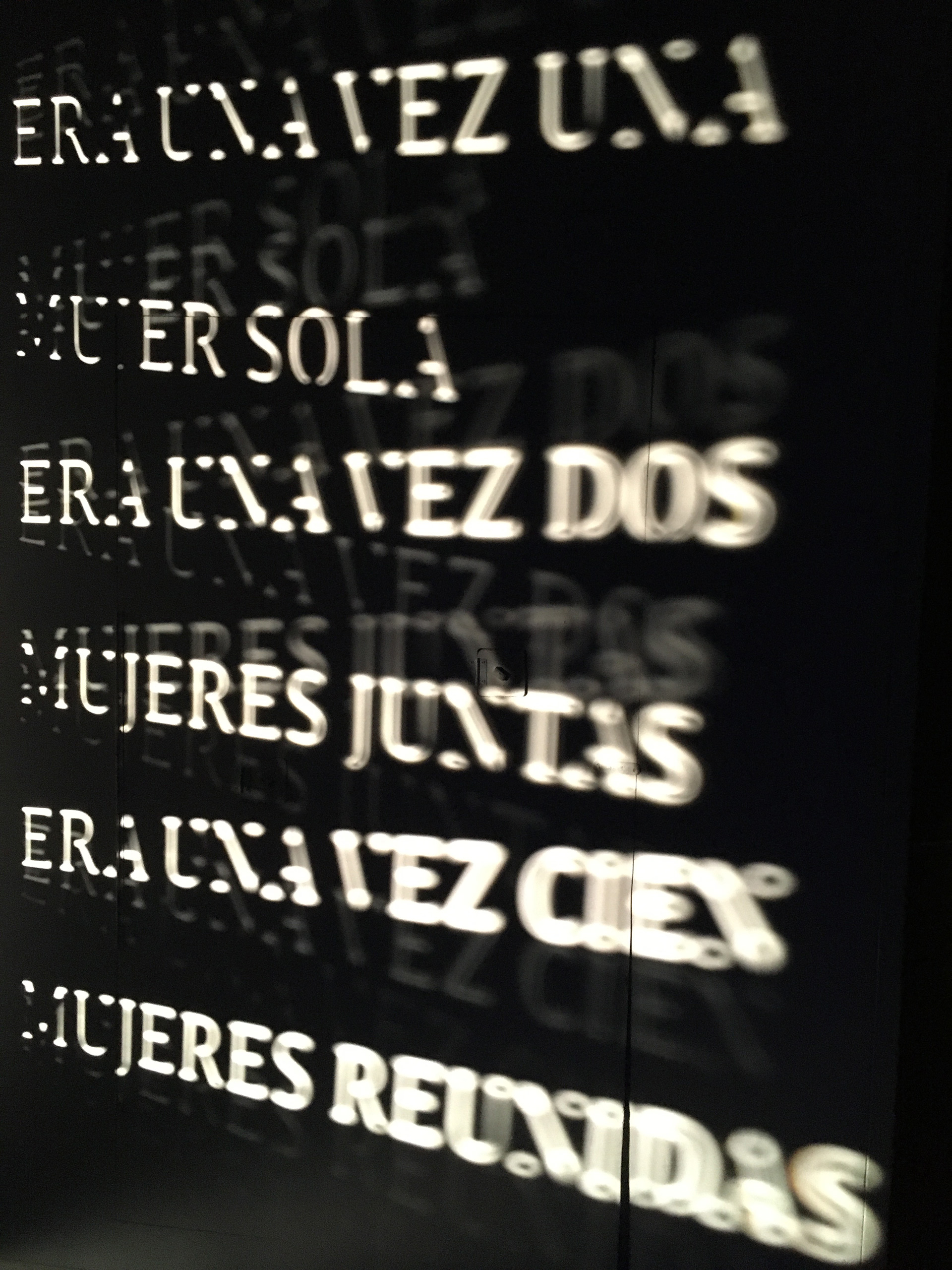

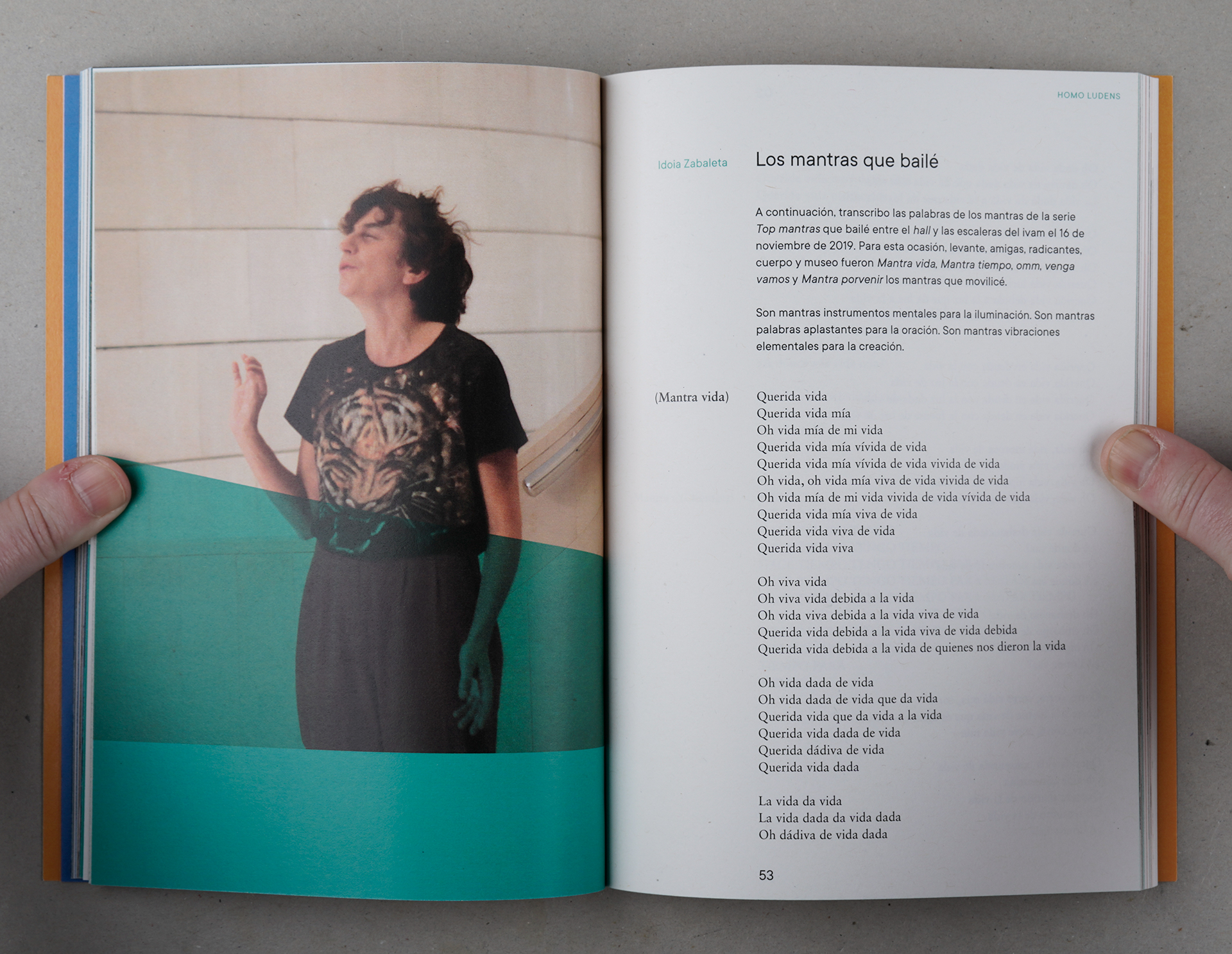

Idoia often says that her dancing has always had a speech, a kind of blah-blah. The question of speech, the distortion of speech, the inclusion of theatrical elements in dance links her to Meredith Monk, for example, but more closely to Itziar Okariz, Amaia Urra, Ixiar Rozas, to a generation of artists linked to performance who have worked on speech, language and the word within a discipline organised around the body. All of them speak but, like Idoia, they reject the clarity of discourse. In the fissures, Idoia uses her own speaking as a way of opening a crack in the primacy of the frontal, central, distanced, flattened gaze. She seeks to touch the other with her words, to appeal to the other, often directly, to try to sum up the distance that separates them. In the Mantras, however, she begins to unfold the potencies of that moving by speaking. The attention has already slipped from the body to language and to the choreographic powers of the spoken word. The Mantras seem an escape path from the way she used language in her previous performances, in a straight line, to go through, like a vector. In order to transcend it, Idoia begins to manipulate what she was using instrumentally to fissure the mutism of a dancing body. In Fissures she used speech to create displacements, movement, after all. But how to think language if not with language itself, how to exercise its movement, how to encourage it, to wave it, how to transcend its frontality? The earliest documented Mantras are audio recordings. Idoia tells us that these Mantras often appear while driving in a car. The landscape moves quickly, the foreground blurs and perspective twists, everything is mutable and fluid outside while moving at high speed, but in the cockpit, driving requires a discipline and technique that puts the body on alert. You have to change gear, respect traffic signs, remember the turn, turn on the indicator. In the collision between these two forms of perception, is where Idoia’s Mantras are often born, like a sonnet. Then she goes to the studio and works on them. There is no outside movement, the white walls, the wooden ceiling of Azala define the space like a constant. The body, on the other hand, is free of constraint. There is no need to mark, reduce or give way. This is where the audio recordings that are the basis of the Mantras are created. In them, a kind of phrases are worked out, repetition structures with tonal variations that are modulated in a serial way. Many of the Mantras start from structures based on binarity (while you X I Y, they X we Y). Once again, the initial elements confront each other. In all of them, Idoia begins to work on the materiality of the voice as a becoming and the saying as a movement. Through the Mantras she focuses her work on all those potentialities that escape from the scheme of modern rational scientific thought and language ceases to be straightforward. In this series, there is a stronger work with sensations, with how it feels to pronounce this or another word, what gesture produces a g, how an m moves me after a g, what images they shape. Idoia twists and plays with language, diction and tone to create images in transformation, to foster an in between that opens up possibilities of zigzagging, swirling, escaping. When I think about the process of creating the Mantras in order to be able to write, I fall into shadows, I think that I am thinking and I become obsessed. The performance aims for a continuous present, I tell myself; that’s what Idoia is looking for. And then I doubt, and a song by Pepe Suero (Andalucía la que divierte, 1978) that I used to listen to with Vicente comes to my mind like a mantra. The song goes like this: “I think I die when I think, I think that thinking I die (…) I think I live when I sing, I want to sing and I can’t (…) I die wanting to live, I think I live when I sing, I want to sing and I can’t, I think that thinking I die, I think I die when I think”.